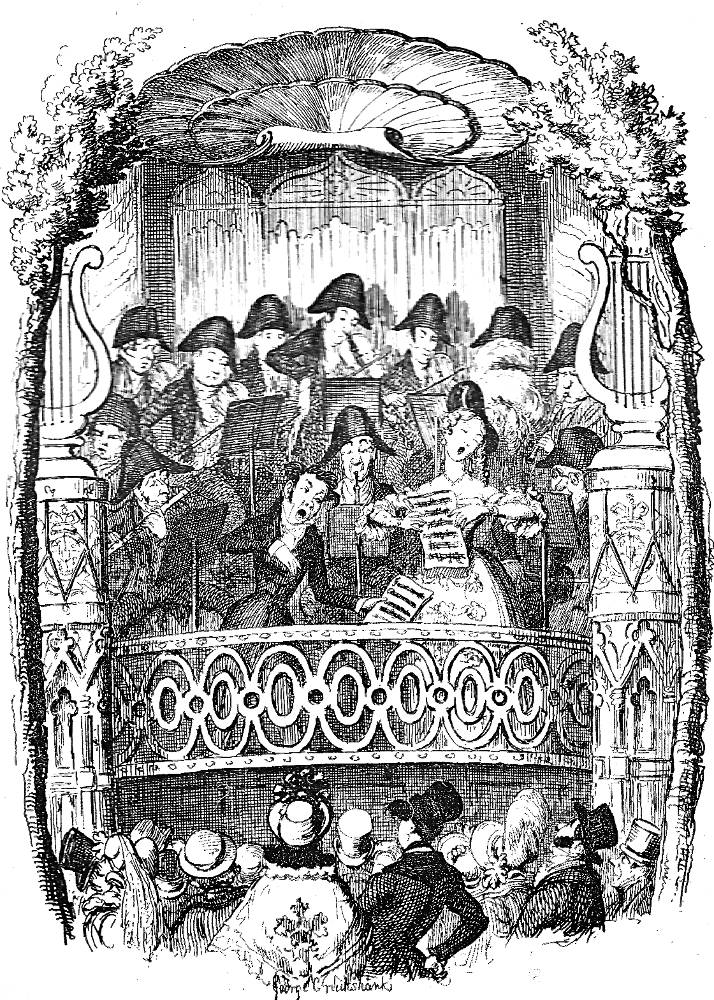

The Pleasure Gardens at Vauxhall, Kennington, as envisaged by George Cruikshank [1839 and July 1842].

Ainsworth's Brief History of The Pleasure Gardens at Vauxhall (1842)

Celebrated throughout Europe, and once esteemed the most delightful place of recreation of the kind, Vauxhall Gardens have been in existence for more than a century; and it rejoices us to find that they are not altogether closed. They were first opened with a ridotto al fresco, about the year 1730, and speedily rising to a high reputation, were enlarged and laid out in the most superb manner. A magnificent orchestra, of Gothic form, ornamented with carvings and niches, and provided with a fine organ, was erected in the midst of the garden. There was likewise a rotunda, though not of equal dimensions with that of Ranelagh, being only seventy feet in diameter, with a dome-like roof, supported by four Ionic columns, embellished with foliage at the base, while the shafts were wreathed with a Gothic balustrade, representing climbing figures. From the centre depended a magnificent chandelier. A part of the rotunda, used as a saloon was decorated with columns, between which were paintings by Hayman. The entrance from the gardens was through a Gothic portal. Moreover, there were pavilions or alcoves, ornamented with paintings from designs by Hogarth and Hayman, appropriate to the place; each alcove having a table in it capable of accommodating six or eight persons, and leading in an extensive sweep to an extensive piazza, five hundred feet in length, of Chinese architecture. This semicircle led to a further sweep of pavilions. A noble gravel walk, nine hundred feet in length, bordered with lofty trees, and terminated by a broad lawn, in which there was a Gothic obelisk, faced the entrance. But the enchantment of the gardens commenced with the moment of their illumination, when upwards of two thousand lamps lighted almost simultaneously, glimmered through the green leaves of the trees, and shed their radiance on the fairy scene around. This was the grand charm of Vauxhall. One of its minor attractions was a curious piece of machinery, representing a miller's house, a water-wheel, and a cascade, which at that period of the art was thought quite marvellous. There were numberless walks and wildernesses in the grounds, and most of the vistas were adorned with statues. In one of them, at a date a little posterior to this history, was a statue of Handel as Orpheus, holding a lyre [i. e., The Vauxhall Handel by Louis François Roubiliac, 1738]. [Chapter X, pp. 185-86]

Commentary: 1741-1859

Vauxhall and Ranelagh Gardens were in direct competition with one another, the latter established in 1741 and the former revitalised in April 1742. The Vauxhall site proved to have greater longevity, closing only temporarily when the owner went bankrupt in 1840, whereas Ranelagh closed for good in 1803. Technically, since the year of the action is supposedly 1744, Ainsworth should be calling the site "New Spring Gardens" as the entertainment venue did not acquire the new name "Vauxhall Gardens" until 1785. However, the novelist is quite correct about the nature of the Vauxhall experience, which included lavish buffets, drink, music, and (after 1798) fireworks after dark in a park-like setting. The supper-box in which the action occurs in the Cruikshank plate is near the Grand Walk, a stately avenue of elms nine hundred feet long and thirty feet wide.

At first, the Gardens were open every day except Sundays, from May till September. Admission was 1s until the summer of 1792, when it was raised to 2s. Vocal music was introduced in 1745, with some of the greatest singers of the day performing at the Gardens, including Mrs. Arne and Mrs. Beddeley. Fireworks were not displayed at the Gardens until 1798 and even then did not become a mainstay. ["Vauxhall, the Oval and Kennington"]

Although its many walks and pathways were ideally suited for romantic assignations, the enormous crowds were attracted by an array of spectacular entertainments, including tightrope walkers, hot-air balloon ascents, classical music concerts, and evening pyrotechnics above the lamp-lit grounds. Admission was free, and the Gardens could only be reached by water via a sixpenny boat ride until the opening of Westminster Bridge in 1750. Changing tastes and a greater range of entertainment options for Londoners, however, led to Vauxhall's decline. Although it closed in 1840 after its owners suffered bankruptcy, it re-opened in 1841, only to suffer permanent closure on 1 September 1859. Vauxhall Gardens opened for the last time on the night of Monday, 25 July 1859.

Thus, when Ainsworth included Vauxhall in The Miser's Daughter, the entertainment venue was very much in operation. The building in the background is "The Orchestra" (new octagonal bandstand erected in 1735), behind which would have been "The Organ Building." The former was possibly the first building in London designed specifically and solely for the performance of orchestral music. "After the construction of the Orchestra, and the appointment of a permanent band, Tyers instituted an admission charge of one shilling, the equivalent of about £12 to £15 today. This charge remained unchanged for almost sixty years" (Vauxhall Gardens 1661–1859: A Brief History). The Orchestra Pavillion rendered the musicians on the raised stage highly visible and audible throughout The Grove. Moreover, the request format for concerts which had been the standard became a thing of the past as the musicians were no longer within easy contact of the audience. Consequently, Vauxhall could now introduce wholly new works by contemporary composers, within a complementary pre-organised programme. With some 1,000 visitors per day over the course of the hundred days in the summer months arriving at Vauxhall Stairs by boat from Westminster Pier, the organizers could repeat or revise the previous evening's program, thereby appealing to the first mass audience gathered strictly for popular music. The evening at Vauxhall would begin at 7:00 P. M. as visitors would enter the grounds on foot through the main gate fronting the south bank of the Thames and proceed along The Grove with the supper boxes lining the walkway on either side.

By the time he came to compose the Vauxhall scene for The Miser's Daughter in the summer of 1842, Cruikshank had already done two fairly well-known illustrations of the pleasure gardens: Vauxhall in 1835, showing the Master of Ceremonies, C. H. Simpson, raising his hat, and Vauxhall Gardens by Day (1839) for Dickens's essay in Sketches by Boz.

On Cruikshank’s Illustrations of Vauxhall

George Cruikshank probably modelled his book illustration for the novel The Miser's Daughter: A Tale (1842) on actual visits to nineteenth-century Vauxhall. However, he may have also consulted such prints and paintings of the eighteenth-century gardens on the south back of the Thames as Antonio Canaletto's View of the Grand Walk, Vauxhall Gardens, with the Orchestra Pavillion, the Organ House, the Turkish Dining Tent and the statue of Aurora (1751). As opposed to the scene painter's panorama, Cruikshank moves in for a close-up, giving an intimate view of the Vauxhall experience in the previous century.

According toWilliam Harrison Ainsworth in The Miser's Daughter, a trip to the pleasure gardens at Ranelagh, Chelsea, and those at Vauxhall was essential for the young aristocrat visiting London in the eighteenth century. His illustrator, Cruikshank, depicts a supper-time scene with the boxes and Orchestra Building illuminated in The Supper at Vauxhall. However, earlier for Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Cruikshank had depicted an afternoon concert in the 1830s, Vauxhall Gardens by Day (1839).

George Worth, in William Harrison Ainsworth, notes of the novel's fashionable settings, "The London pleasure haunts of the day, in each of which important action takes place, are carefully described by Ainsworth. . . . The virtues of this novel [The Miser's Daughter] are clearly recognized when it is contrasted with a much feebler late novel set at almost exactly the same period, Beau Nash, in which mid-eighteenth century Bath . . . has none of the vivid ambience we sense in the mid-eighteenth-century London of The Miser's Daughter" (p. 68). Among these well-known eighteenth-century pleasure gardens Ainsworth and Cruikshank describe in the 1842 novel are the Mall, the Folly on the Thames, the gardens at Mary-le-bone, and Ranelagh gardens. In the July 1842 instalment in Ainsworth's Magazine, Volume 1, Number 7, they transported nineteenth-century readers to the gardens at Vauxhall as they were a century earlier.

Related Materials

- Vauxhall Gardens

- The Pleasure Gardens at Ranelagh, Chelsea

- The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850

- The Development of Pantomime, 1692-1761

- Music, Theater, and Popular Entertainment in Victorian Britain

- London Recreations from Dickens's Sketches by Boz (1839)

- Greenwich Fair (1839)

- Mr. Lambkin goes to a Masquerade as Don Giovanni (1844)

References

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. With 20 illustrations by George Cruikshank. First published in 3 volumes by Cunningham and Mortimer, London, 1842. London, Glasgow, and New York: George Routledge, 1892.

Coke, David, and Alan Borg. Vauxhall Gardens 1661–1859: A Brief History. Based on Vauxhall Gardens: A History (Yale U. P., 2015). http://www.vauxhallgardens.com/vauxhall_gardens_briefhistory_page.html

"Vauxhall, the Oval and Kennington." The Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens — Detailed History. https://www.vauxhallandkennington.org.uk/sgdetail.shtml

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Last modified 25 June 2018