This is the first full biography of an English architect who has had little attention from historians: Gordon Vowles has done well to bring him out of the shadows. In the introduction Vowles explains that even if Henry Clutton was not in the same league of such well-known figures as Sir Charles Barry, Augustus Welby Pugin, Sir George Gilbert Scott and George Edmund Street, he still made a name for himself as a successful and prolific architect. He may not have designed any landmark public or commercial buildings, but he built, extended or restored many churches, built or improved some grand country houses, and designed a number of schools and educational institutions.

His career got off to an excellent start: he was apprenticed to the London-based architect Edward Blore and worked in Blore's office for ten years, from 1835-45, ending as his chief assistant and overlapping with other apprentices such as Francis Penrose, William Burges and P.C. Hardwick. His first private house commission, Merevale Hall, was begun from Blore's office.

Clutton did have some setbacks after that, and these help to account for his comparative invisibility. He was unlucky enough to lose out on several major commissions. The first of these occurred after he and Burges travelled on the continent together. They submitted a design for the competition for Lille Cathedral in 1854-55, and indeed won it, but the prize was rescinded in favour of a French architect. Soon after this unfortunate experience, the two young architects fell out. The cause is "not entirely clear" (Vowles 15), but there was a strong difference in their personalities. Burges was talented and eccentric while Clutton was more down to earth and conservative.

Clutton's conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1857 was a defining moment in his life and also counted against him in some circles, to some extent blighting what could otherwise have been a more brilliant career. However, he was doing well enough to embark on marriage: he married Alice Ryder, who was twenty years younger than him and the daughter of a Catholic convert, in 1860. It appears to have been a happy marriage and the couple produced a typically large family for that time — nine children, five boys and four girls.

Bad luck struck again after that. In 1867 he was chosen to be the architect of Westminster Cathedral and spent six years working on an ambitious Gothic Revival design, but was then shuffled off with no compensation in favour of his former pupil J. F. Bentley (whose design, of course, was strikingly different). He lost out too in the Brompton Oratory competition, and failed to gain the surveyorship of Salisbury cathedral in spite of having repaired the cathedral Chapter House.

St Lawrence's, Bedfordshire, the parish church of Willington, restored by Clutton in 1876-77. Source: Isherwood, facing p.221.

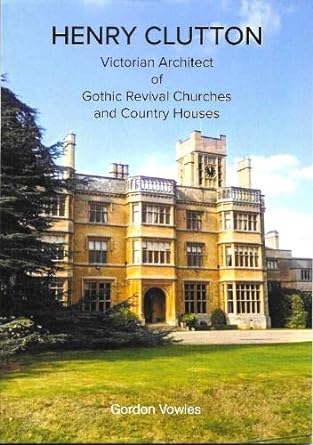

But Clutton, who was nothing if not persevering, had more success working for the Duke of Bedford who initiated a program of church restoration throughout the county. More than ten churches were repaired or rebuilt, including the venerable and historic parish church St Lawrence's, Willington, shown on the right here. Work was also carried out on the Bedford estate at Covent Garden. And, after all, Clutton's conversion brought rewards as well as disappointments. He managed to run a busy practise building churches all over the country for both Catholic and Anglican worshippers. He also made friendships with wealthy clients for whom he designed large and elaborate country houses. Following on from Merevale Hall came others, notably Minley Manor and Ruthin Castle. The house featured on the front cover of the book is Old Warden Park, Bedfordshire.

Minley Manor.

Although most of these buildings have been been considerably altered and adapted, as their High Victorian style went out of fashion and was denigrated by the post-World War II generation, enough remains for us to appreciate the scope and style of his architectural vision. For example, his considerable additions to the Cliveden estate included a handsome water tower, which is still much admired.

The clock-tower at Cliveden.

On Clutton's death the Roman Catholic Times recorded that he "was the boldest of architects, quick to incorporate new principles and to explore new fields" and should be considered "among the best of which our modern churches can boast" (qtd.in Vowles 75).

Vowles illustrates a good range of Clutton's work with twenty colour photographs and includes some interesting information on the social and financial background of Victorian architects. The rich were getting richer and the lower orders rapidly expanding with a shift from labouring in the country to town dwelling factory-workers. All classes were in need of houses to live in and - especially in this period of religious enthusiasm - churches in which to worship. Architects, builders, artists and sculptors all flourished. In this climate, despite the fact that he began losing his sight before he was sixty, Clutton achieved enough to die a very wealthy man. Vowles is to be commended for showcasing his work now that, fortunately, Victorian architecture is being looked at more favourably, and efforts are being made to preserve it for posterity.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Vowles, Gordon. Henry Clutton: Victorian Architect of Gothic Revival Churches and Country Houses. Pbk. Willington: The Gostwick Press, 2022. pp. 78. £13.50. ISBN 978-0956566386. Note that the proceeds from the sale of this book go towards the upkeep of St Lawrence's, shown above.

[Illustration source] Isherwood, Constance. "Willington Church, Bedfordshire." The Home Counties Magazine Vol. VIII (1906). 225-230. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 20 May 2024.

Created 19 May 2024