J.A. Chatwin, from a local magazine of the 1870s (information kindly

provided by the parish office of St Augustine of Hippo, Edgbaston).

Biography

Julius Alfred Chatwin (1830-1907) was born in Birmingham on 27 April 1830. His father John (1796-1855) was in the city's flourishing button-making trade, but his drawing master at the King Edward VI School (the same school as that attended earlier by the architect John Gibson) was interested in architectural design, and his aptitude for this set him on a different course. After leaving when he was about 16, he attended a local Academy of Arts, and then joined a firm of prominent building contractors, Branson & Gwyther, as a draughtsman. There he began designing buildings himself, his first houses being "an Italianate pair" dating from 1850 (Little 124).

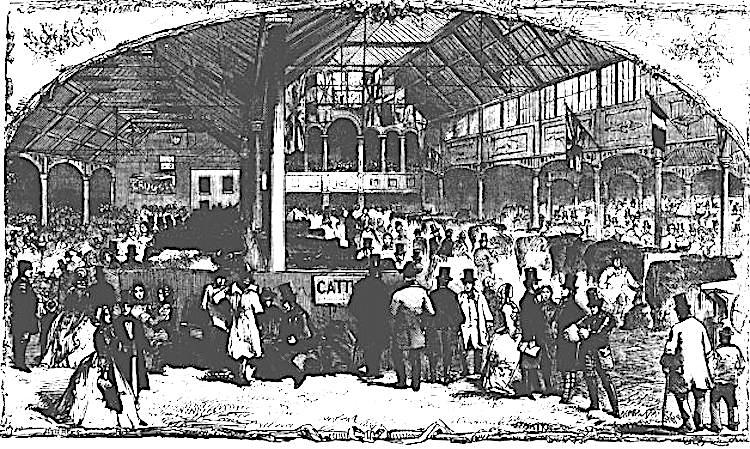

That same year he achieved a notable first, designing for the firm a permanent exhibition hall to replace an earlier wooden structure, The new hall predated the Crystal Palace in London. Indeed, the first agricultural show held at Birmingham's Bingley Hall was recorded in the same issue of the Illustrated London News as that featuring Prince Albert's visit to the building site of his own project in Hyde Park. Unlike the Crystal Place, Bingley Hall had a solid brick exterior, utilizing materials originally intended for railway projects, needed here more urgently in view of the upcoming exhibition. Perhaps as a result, the structure lasted much better than its London counterpart. Over a hundred years on, it would be the Birmingham venue for the Land Travelling Exhibition during the Festival of Britain in 1951. However, in the end it did meet the same fate as the Sydenham Crystal Palace: having been greatly damaged by fire, it was finally demolished in 1984. But, clearly, in 1850 Chatwin was well on the way to a distinguished career as an architect.

The interior of Bingley Hall during a cattle show recorded in the Illustrated Weekly News of 6 December 1862, p. 140 (scanned by the author).

More preparation for such a career was still needed. In the following year, Chatwin went to London, where he served his articles with Charles Barry and became part of the talented team of architects working under him while the new Palace of Westminster was being completed (see Shenton 116). This was an experience that may well, as Tim Bridges suggests, have led to his own preference for blending classical proportions with a more ornate layer of decoration (see "Chatwin, J. A."). He also took classes in design at the Royal Academy Rooms in Somerset House on the Strand. Then in 1855, the year his father died, he returned to his native Birmingham and set up his own practice, first on Bennett's Hill then, in 1858, in more spacious premises on Temple Row. Here he soon established himself as a leading city architect, designing or extending many churches, nearly always in the neo-Gothic idiom, and showing "a remarkable facility for providing buildings which were inexpensive and structurally sound, and at the same time satisfactory both aesthetically and in terms of accommodation" (Stephens). He also restored many older churches, such as the central church of St Martin's, and his stylistic adaptability paid off handsomely in the creation of a new baroque chancel at St Philip's — later to become Birmingham Cathedral. "Chatwin's work here possibly comprises his most memorable ecclesiastical architecture" (Bridges, "J.A. Chatwin," 114). In the commercial sector, at the time of Birmingham's greatest expansion, he designed buildings for banks, especially LLoyd's, and offices, which were mostly (as might be expected from someone who had trained under Barry) ornately Renaissance in style.

The preserved tower and spire of Birmingham's St Martin's

rising over the market stalls (photo by the author).

Chatwin had now achieved many honours. He became a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (FRIBA) as early as 1863, as well as a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (FSAScot), and an Associate of the Royal British Society of Sculptors (ARBS). It must have pleased him when he became architect to the Governors of his old school in 1866. Marriage in 1869 to Edith Isabel Boughton had secured the future of his firm: he took their son Philip Boughton Chatwin (1873-1964) into partnership in 1897. From then on it became J. A. Chatwin & Son.

In another sign of his preeminence, Chatwin was very much involved in the cultural life of the city, both collecting and promoting art: he became President of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists in 1883. Most of his commissions were in the Birmingham area, or at least in the Midlands — from 1891 he was the architect to St. Mary's Church in Warwick. But despite remaining what might fairly be called a top-tier provincial architect, his fame must have spread: he did some work in Bournemouth (on St Andrews, Bennett Street) and Malvern (on the Firs, College Grove), for instance. He was even commissioned to design a Maharajah's glass palace, although, due to an unfortunate prediction on the Indian side, this was never actually executed. He died at home in Edgbaston, on 6 June 1907, leaving the firm in the capable hands of his son — who would one day repair war damage to the cathedral that his father had worked on, with such acclaim. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Works

- Bingley Hall, Birmingham

- Chancel of St Philip's Cathedral

- St Martin's, Birmingham

- St Augustine of Hippo, Edgbaston

Bibliography

"Birmingham and Midland Counties Agricultural Association." Illustrated London News Vol. 17 (14 December 1850): 458-60. Internet Archive. Web. 4 December 2024.

Bridges, Tim. "Chatwin, Julius Alfred (1830–1907), architect." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 4 December 2024.

_____. "J.A. Chatwin." Birmingham's Victorian and Edwardian Architects. Edited by Phillada Ballard. Birmingham: Oblong Creative, for the Birmingham and West Midlands Group of the Victorian Society, 2009. 89-122.

"The Cattle Show and Cattle Market." Illustrated Weekly News Vol.II, No. 61 (6 December 1862): 460-61. Internet Archive. Web. 4 December 2024.

"The Late Julius Alfred Chatwin (F)." Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi. Web. 4 December 2024.

Little, Bryan. Birmingham's Buildings: The Architectural Story of a Midlands City. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles, 1971.

Obituary. The Builder 92 (15 June 1907): 728. Internet Archive. Web. 4 December 2024.

Shenton, Caroline. Mr Barry's War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Stephens, W. B., ed. "Religious History: Churches." A History of the County of Warwick. Vol. 7, the City of Birmingham. London: Victoria County History, 1964: 354-61. British History Online. Web. 6 December 2024. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/warks/vol7/pp354-361.

Created 8 December 2024

Last modified 3 January 2025