Scan, formatting and photographs by the author, and (where specified) by Colin Price. [You may use the photographs without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images for larger pictures.]

St Philip's Church in the Mid-Nineteenth-Century

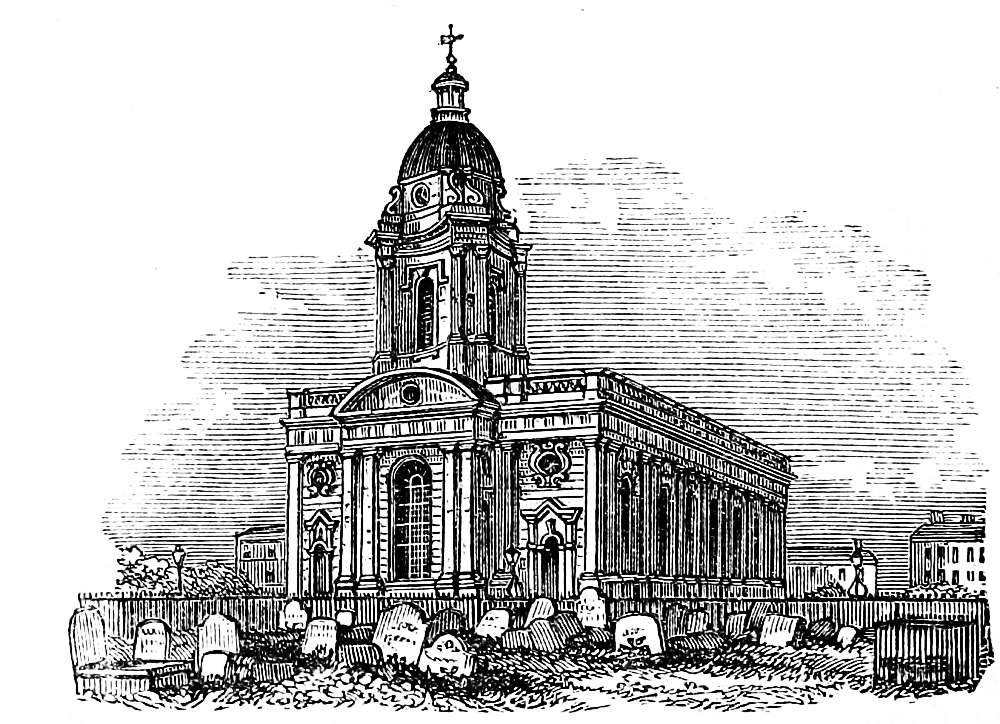

St Philip's Church, Birmingham, as shown in Birmingham Illustrated (1851), p. 56.

Designed by the architect Thomas Archer (1668-1743), St Philip's was built in the first quarter of the eighteenth century on high open land, in what was then a small Midlands town. However, it was no ordinary parish church. As Andy Foster says, "It is exceptional, an early and sophisticated Baroque design by ... the only English architect who knew the Italy of Bernini and Borromini" (4-5). Birmingham Illustrated describes it thus: "The church was commenced in 1711, and was consecrated in 1715. It is built in the mixed Italian style, and is much admired by architects. Its pedestal line, its lofty pilasters, its handsome balustrade, its well proportioned tower and cupola, have a pleasing effect" (57). It was built of local bricks faced with local limestone, which later needed recasing, and stands in the Colmore Row district. The tower was not completed until 1725 ("A Brief History," 1).

St Philip's Cathedral Now

Left to right: (a) The west front. (b) Looking along the length of the cathedral towards the tower.

The church was designated a cathedral in 1905, with the creation of a new diocese. In the later Victorian period, two prominent local architects had played a part in preparing St Philip's for its new role: Yeoville Thomason, architect of Birmingham's Council House and Museum and Art Gallery, redecorated the interior in 1871; and J.A. Chatwin, whose "churchbuilding dominance" in Birmingham was unchallenged (Little 27), extended it to the east, giving it a chancel, in 1883-84. Chatwin also made some other alterations, and is important for having facilitated the arrangement whereby Edward Burne-Jones designed the four stained glass windows. These "highly important works of the Pre-Raphaelite movement" are the cathedral's main treasures ("A Brief History," 2).

The interior. Left: Looking towards the chancel, added by Chatwin, with Burne-Jones's "Annunciation" window behind the altar. Right: The fine ironwork of the altar rails.

In 1851, Birmingham Illustrated had described the interior as having a capacity for 1800 persons, and as being "very handsome; lofty arches support the roof. There are two side and one end galleries, which are well lighted, and commodiously fitted up with pews, as is the body of the church" (57).

Closer view of the sanctuary, with the glowing central East window (photo by Colin Price). The edges of the two adjacent windows can be seen just beside the columns on each side.

Two changes since then, the absence of an end (i.e., west) gallery and the replacement of pews by seating, are immediately apparent. The latter is common enough, and happened later, in 1905, under the direction of Chatwin's son Philip (Foster 41). But removing the gallery below the tower was part of the elder Chatwin's plan in 1883-84, making the west end more spacious and helping to balance the more striking opening up of the chancel area. This latter improvement was the major one, when a shallow apse gave way smoothly to "an enhanced chancel and sanctuary, dominated by classical columns and an ornate, coffered ceiling with gilded flower detailing" (Foster 41). Vestries were also added at this time, either side of the chancel. The result is very effective, and much praised as a rare example of English Baroque, rich without extravagance.

Liaising with Burne-Jones over the spectacular windows was also a vital aspect of the elder Chatwin's involvement. It might seem a shame that, thanks to the columns in the apse, all three east windows are not visible from the nave. But an audio tour available on the cathedral's website at the time of writing makes a virtue of this. It explains that the initial obscuring of the side windows "gives a fascinating theological effect for worshippers coming forward to receive Communion at the High Altar. The Christian faith is revealed as you approach, before being confronted by the Last Judgement when you turn around and look towards the tower at the west end." The completion of Burne-Jones's iconographic programme was, of course, directly facilitated by the removal of the gallery there. The new elements introduced by Chatwin all worked together wonderfully well.

Left: Looking to the west end from the chancel. Right: Closer view of the tower area, so usefully opened up by Chatwin.

As cathedrals go, St Philip's is still quite small, but, as its Grade I listing suggests, it continues to be very well regarded. Indeed, Foster considers St Philip's "a building of national importance," quoting Alexandra Wedgwood's description of it as "a most subtle example of the elusive English baroque" (40). It is worth adding that recent conservation work on the windows has restored them to their original brilliance.

Links to Related Material

- Edward Burne-Jones's central east window, the Ascension

- Edward Burne-Jones's left east window, the Nativity

- Edward Burne-Jones's right east window, the Crucifixion

- Edward Burne-Jones's west window, the Last Judgment

- Richard Westmacott's Memorial to Beatrix Outram on the west wall

- Church and Dissent in Birmingham, 1851-1893

Bibliography

"Birmingham Cathedral: Our History and Heritage." Cathedral Website. Web. 9 December 2024.

Birmingham Illustrated: Cornish's Stranger's Guide Through Birmingham. London: Cornish, 1851. Internet Archive. Web. 6 September 2012.

"Cathedral Church of St Philip." British Listed Buildings. Web. 9 December 2024.

Foster, Andy. Birmingham. Pevsner Architectural Guides. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2005.

Little, Bryan. Birmingham's Buildings: The Architectural Story of a Midlands City. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles, 1971.

Created 6 September 2012

Last modified 9 December 2024