“The interior of Keble Chapel, consecrated in 1876, was Butterfield's last masterpiece in brick.” — Paul Thompson.

Left: The chapel seen from just inside the door. Right: The chapel ceiling. Click on images to enlarge them.

Thomson on Butterfield's subtle use of polychromy in the chapel

According Paul Thomson, Butterfield's many hours studying St. Marks's in Venice made him emphasize the mosaics that “dominate the interior of Keble College Chapel and make it at first sight one of the least attractive of Butterfield's later displays of polychromy” (246). A “longer look,” however reveals the beauty of the interior:

The chapel is treated as a single, vast space, the whole effect concentrated on the outer surfaces. All the furniture is kept deliberately low: only dark long lines of seats, and a light open wrought metal pulpit and altar rails. The choir seats are pushed back to form a great open floorspace at the east end, paved in white and grey stone, with encaustic tile patterns in yellow, plum, emerald green arid sea-green. These colours are taken up in the walls. The lowest stage is a bold wall arcade, the surface behind of glazed plum-coloured brick, with thin sea-green strips and broader bands of formalized mastic patterning set in stone-flowers, suns and tendrils. Next come the mosaics, rather softer in colour: green, pink, pale blue, a limp yellow, red and white. The colours seem in fact too soft for the strong archaic lines of the figures and their powerful architectural setting. Surely the white ground is especially mistaken?

Above the mosaics, however, the colouring reaches a superb climax. Gibbs' windows are a complete success, light but glowing with scarlet, mauve, yellow and blue-greens. Between them in the upper walls the brick turns to a soft vermilion red, crossed by grey and buff bands and light diapers, rising to chequer pattern up under the vaults. At the springing of the vaulting the great grey wall shafts, which have risen from the lowest stage of the wall, give way to the enchantingly delicate pink and terracotta patterning of the ribs; the rhythm of the patterning quickening as the ribs cluster. Not only the ribs, but the entire surface of the vault is painted, with formalized patterns of jointing in broad zones of buff, sea-green and grey. Yet the result is not, as so often with this type of decoration, a maze of lines reducing the structure to a toy. In the Keble vaults the lines are kept deliberately soft, and it is the subtle colouring which prevails, modulating the clean lines of the vault. The effect is one of extraordinary freshness and freedom in contrast to the stronger shapes and tones of the lower walls; and, once discovered, the eye will return again and again to the strange beauty of this painted ceiling. [246-49]

Butterfield's chapel roof and ceiling

Paul Thompson points out that throughout his career Buttefield used five kinds of roofs — “vaults, flat roofs, collar-braced, truss-braced and tie beam” — and he used a vaulted ceiling and roof only twice in later structures, both in major buildings: All Saints Margaret Street and Keble College Chapel. In the college chapel

the vault is a pointed tunnel similar to All Saints', but slightly less sharp, with clustered wall shafts brought down to the ground, so that the effect is much more static, the identity of each bay emphasized, and the eastward movement reduced. These qualities, together with the painted decoration of the chapel, and the emphatic horizontal thickening of the lower wall, make Butterfield's debt to the upper church of S. Francesco at Assist much clearer than it was at All Saints'. [171-72]

Left: The choir. Right: Doorway to the outside.

Details of wall and ceiling.

At the springing of the vaulting the great grey wall shafts, which have risen from the lowest stage of the wall, give way to the enchantingly delicate pink and terracotta patterning of the ribs; the rhythm of the patterning quickening as the ribs cluster. Not only the ribs, but the entire surface of the vault is painted, with formalized patterns of jointing in broad zones of buff, sea-green and grey. Yet the result is not, as so often with this type of decoration, a maze of lines reducing the structure to a toy. In the Keble vaults the lines are kept deliberately soft, and it is the subtle colouring which prevails, modulating the clean lines of the vault. — Thompson, 247]

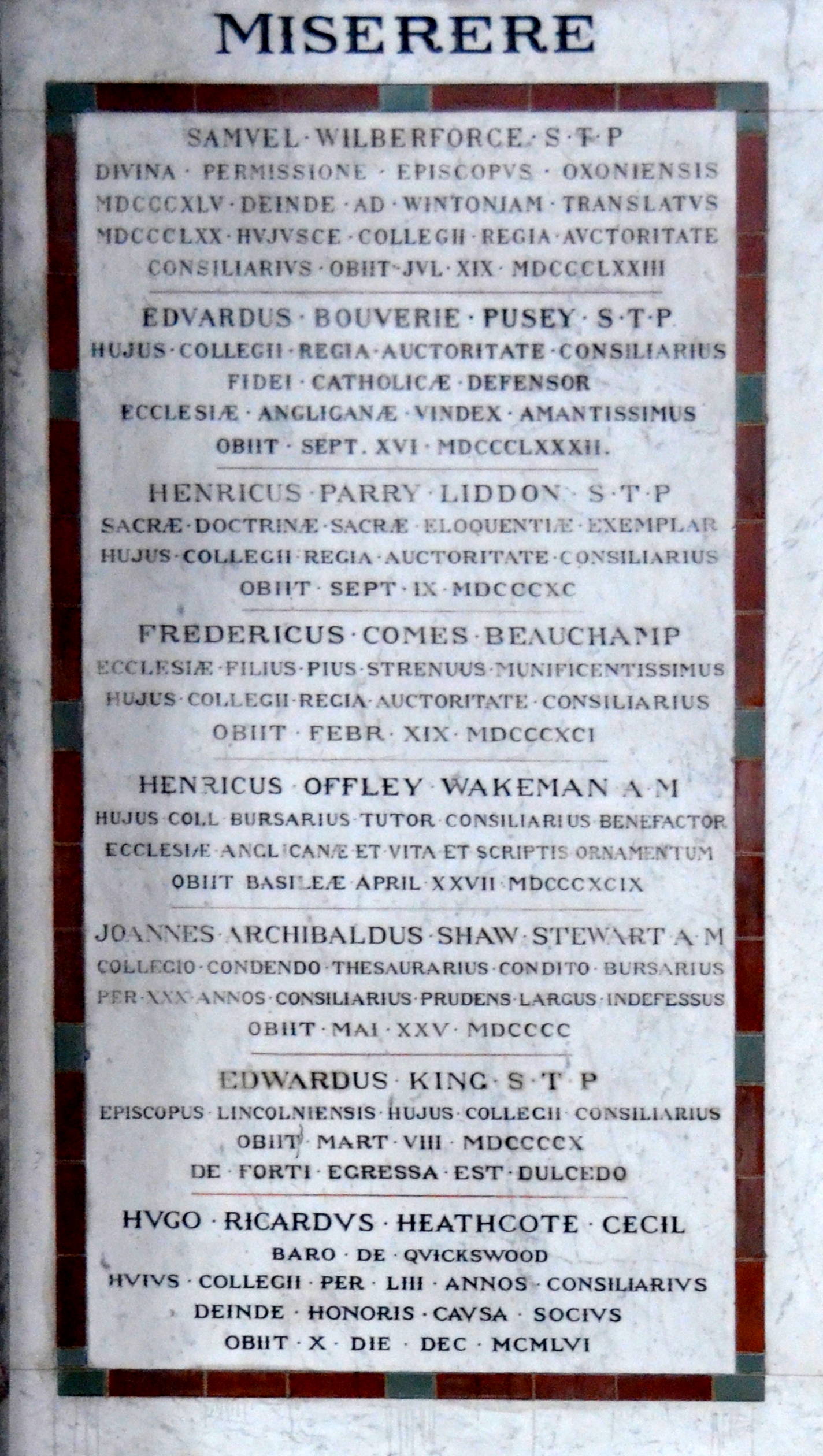

Left: The organ loft. Right: Memorial plaque. The memorial to leading clergymen includes Pusey and Liddon, two leading Tractarians after whom college quadangles were named. Perhaps surprisingly Samuel Wilberforce, an Evangelical bishop, also appears.

Left to right: two lecterns and a view of the encaustic tile floor [see another photograph of the tile floor with a different design]. “The choir seats are pushed back to form a great open floorspace at the east end, paved in white and grey stone, with encaustic tile patterns in yellow, plum, emerald green arid sea-green. These colours are taken up in the walls.”

Three details from the rear of the chapel — Left to right: two places reserved for college officials (the middle one for the bursar), and varied stone columns near the doorway.

Other images of Keble College, Oxford, and related materials

- College Exterior

- The Chapel Exterior

- The Chapel Interior

- Pusey Quad

- Liddon Quad including the Hall

- Mosaics in the chapel

- Victorian Rogue Architecture

- John Keble and the Oxford Movement

Coming soon

Photographs, formatting, and text by the author. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Eastlake, Charles L. A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green; N.Y. Scribner, Welford, 1972. Facing p. 261. [Copy in Brown University's Rockefeller Library]

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. “The Pelican History of Art.” Baltimore, MD: Penguin, 1963.

Thompson, Paul. William Butterfield, Victorian Architect. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1971.

Last modified 23 August 2012