This is Chapter XVII ("Illustrators of the Poems and Novels") of Hammerton's comprehensive book about Meredith, George Meredith in Anecdote and Criticism (see bibliography for full details). It has been formatted for our website, along with illustrations from book, and some extra ones from our own website, by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on all the images for more information, and to enlarge them. Links have been also added where appropriate and page numbers are given in square brackets.

To all but collectors and connoisseurs it may be something of a surprise to know that the illustrators of Meredith are worthy of notice. Yet the illustrations of his poems and his novels, if collected, would make a large and interesting portfolio. The most important of them are also the least familiar; they take us back to that golden age of English wood-engraving in the early 'sixties, when Millais, Holman Hunt, Sandys, Tenniel, Keene, and "Phiz" were drawing their little pencil pictures for Once a Week, and the books of the period, now eagerly and wisely sought after by collectors. In the present work some of the most noteworthy of these engravings have been carefully reproduced, but the subject as a whole is of sufficient bibliographic importance to warrant more than can be conveyed in the "legends" of the cuts.

Sir Gawain and his bride, by John Tenniel, 1859.

There are several remarkable facts associated with the debuts of Meredith and his long survival. It was noted, for instance, that Mr. W. M. Rossetti, who reviewed Poems of 1851 on the first appearance of the volume, was alive to congratulate the author, fifty-seven years later, on the attainment of his eightieth birthday, and now survives him. It may also be mentioned as an interesting fact that the first artist to illustrate anything written by Meredith was Sir John Tenniel, who made the admirable drawing of Sir Gawain and his bride that accompanied "The Song of Courtesy," the first contribution from the poet to Once a Week, dated July 9, 1859 ("Like the true knight, may we / Make the basest that be/ Beautiful ever by Courtesy!" By permission of Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew & Co.). Almost half a century later, Sir John was alive to sign the address presented to Meredith on February 12, 1908, though, oddly enough, his name was not among the signatures. This was Tenniel's only illustration to Meredith's words, and it is thoroughly characteristic of the artist's manner, which in his earlier career, as in his prime, was marked by a free line and a supple grace of figure that in later years tended to harden into certain rigid conventions.

The next poem in Once a Week was printed just three weeks [374/75] later, and Hablot K. Browne supplied the cut, which is not a success, and is quite unlike the familiar Frenchified style of "Phiz." Here and there it is out of drawing; the expressionless features of the women, the looseness of the grouping and the general feeling of emptiness, hardly make it a worthy pictorial interpretation of "The Three Maidens," but I reproduce it none the less, as it is not without interest to-day. To "Phiz" was also allotted the illustrat- ing of Meredith's next two poems, "Over the Hills" (August 20, 1859), and "Juggling Jerry" (September 3, 1859), in the same periodical. Here we find the illustrator more happily inspired. There is spirit and movement and a touch of atmosphere in the vignette to the first-named poem, while the simple pathos of Juggling Jerry's end is at least suggested with some imagination in the second woodcut. "Phiz" was also the illustrator of "A Story-telling Party," signed "T," in Once a Week, December 24, 1859, which Sir Francis Burnand has told us was written by Meredith, to whom Burnand had related some of the stories; but though much more in the vein of the artist as we know him in his illustrations to Dickens, I have not reproduced either of the comic illustrations which accompany that merry fiction.

Juggling Jerry, by Phiz, 1859.

Most noteworthy of all these Once a Week woodcuts are the three next in succession, the work of Sir John Millais. "The Crown of Love" (December 31, 1859) gave the artist good scope for a drawing informed with passion and poetic feeling, which, in a beautifully balanced composition, he has expressed to perfection. But "The Head of Bran" (February 4, i860) was an even better opportunity for the pencil of a master, and here we have a picture of real distinction, entirely worthy of its subject. There is less that is characteristic in Millais 's woodcut to "The Meeting" (September 1, i860), but there is a quiet beauty and a homely touch in it that suits the subject admirably.

Of the other two illustrated poems in the same periodical, "The Patriot Engineer" (December 14, 1861) has a typical illustration by Charles Keene, every touch of character being closely observed and portrayed with the precision we always expect and never miss in the work of that great genius in black and white. The decorative detail and studied beauty of line and composition of the Pre-Raphaelite school find an excellent example in the masterly drawing by F. A. Sandys, with which "The Old Chartist" was adorned in the issue of February 2, 1862.

Left: The Old Chartist, by F. A. Sandys, 1862. Right: The Meeting, by Millais, 1860.

Were these the sum total of the illustrations to Meredith, they [375/76] would still be quite a noteworthy group; but while they are in many ways the most interesting, and contain at least three of the gems of the whole collection, their removal from the portfolio would have no appreciable effect on its bulk.

Illustrations of Evan Harrington

In going through the illustrations to Evan Harrington to-day one feels that it was on the whole a happy chance when the editor of Once a Week gave the story to Charles Keene to illustrate. Of all the author's novels this is the only one in which Keene could possibly have felt at home. It moves at times along the same paths of character which the artist was wont himself to pursue, and if at times it rises into the rarer atmosphere of high comedy, demanding of the artist a conception of beauty rather than character, Keene does not altogether fail even then. Here I have chosen from the forty-one illustrations a selection, which is at once typical of the whole series and of intrinsic artistic interest.

There is quiet dignity and strength in the picture of the Great Mel on his deathbed, with Mrs. Mel and Lady Rosely standing by. In every sense this is a model of story illustration, the detail being carefully studied, and yet the result is an admirably balanced composition. But of course we have Keene in his element when he is showing us old Tom Cogglesby's arrival at Beckley Court in his donkey-cart, and perhaps best of all in his drawing of the two quaint brothers over their Madeira at the Aurora. The languorous, affected manner of the Countess de Saldar he suggests very cleverly in his cut for Chapter XIX of the novel, but perhaps he makes that remarkable woman a thought too fleshy. He was always less suc- cessful with women than with men, and any student of his work in Punch will remark how seldom he introduced women into his drawings. We do not feel, for instance, that the beauty of Rose Jocelyn is realised in either of the illustrations I reproduce, but Evan Harrington is conceived on the lines of the author in both, as again in the very striking picture of him on horseback awaiting the onset of Laxley and Harry. The vignette of Evan's meeting with Susan Wheedle I have also thought worthy of reproduction, for though it lacks definition in the lower part, and the hands of the girl are out of drawing very badly, it has a fine sense of vigour and dramatic colour.

Three of Keene's illustrations for Evan Harrington (1860). Left to right: (a) The death of the "great Mel", by Charles Keene (Hammerton, facing p. 212). (b) Tom Cogglesby's arrival at Beckley Court (Hammerton, facing p. 204) (c) Tom and Andrew Cogglesby at the "Aurora" (Hammerton, facing p. 200).

On the whole, Keene's illustrations are not an impertinence to the novelist, as so many illustrations of fiction are to-day. Where they lose somewhat as pictures is in a too conscientious effort to [376/77] stick to the text, but it is a fault that, save where he falls short of feminine grace, is to be accounted a virtue in an illustrator. None of these woodcuts have ever been printed in volume form, I think, and Mr. Bernard Partridge supplied the frontispiece to the story in the "New Popular Edition."

If we could have had a combination of Keene and Du Maurier to illustrate Evan Harrington the result would have been as nearly perfect as it would be possible to attain; the one giving character, the other grace and that "polite" touch which was foreign to Keene's work. But George Du Maurier — Meredith's most important illustrators, it will be noted, were both Punch men — did the illustrations for Harry Richmond when the story appeared in Cornhill, and these charming drawings translate us at once into the realm of high comedy. By permission of Messrs. Smith Elder and Co., I am able to give a selection of Du Maurier's drawings.

Two illustrations by George Du Maurier for Meredith's The Adventures of Harry Richmond (1870-71). Left: Roy carrying Harry away from Riversley, facing p. 136. Right: Richmond Roy Meets Squire Beltham, facing p. 168.

The picture of Roy carrying his son Harry in his arms away from Riversley through the "soft mild night," that had witnessed the great storm between Squire Beltham and his son-in-law, is finely studied, and if that of Harry and Temple meeting the Princess Ottilia is on more conventional lines it is still instinct with grace and movement. Then, do we not see the very man, the splendid figure of romance, in the illustration of Richmond Roy, smoking his cigar and flipping idly the strings of his guitar, as he chats with Harry and Temple in "High Germany"? And again, years later, when he re-introduces his son to Ottilia at Ostend? Then the picture of Ottilia, "like a statue of Twilight," makes one wish the same artist had given us his conception of the Countess de Saldar. The interest of the other drawings I have chosen centres in Richmond Roy — the figure of this great character having fascinated the artist as thoroughly as it does every reader of the book — and we see him in his strength and power at his meeting with Squire Beltham on the eve of his "grand parade," confounded when the squire "has his last innings" and the grand parade is over, and towards his sunset when Harry returns to find Janet Ilchester the stay of his sinking father.

Other Illustrators

In the "New Popular Edition" Mr. William Hyde has drawn a frontispiece for Harry Richmond which is totally unlike anything of Du Maurier's. Instead of high comedy, which is always the note of Du Maurier, Mr. Hyde has given us a dramatic and masterly picture of Riversley on the great night when Roy came hammering at the door; the lighted windows, the stormy sky, and [377/78] full moon, are all suggestive of the tragic, but the picture is wholly admirable. A few notes on the other illustrators of the edition may here be added. Mr. C. O. Murray imparts a fine old-fashioned touch to his picture of "The Magnetic Age" for Richard Feverel, which was drawn in 1878; there is but little character in the frontispiece to The Egoist by Mr. John C. Wallis, and Mr. Leslie Brooke's rather feeble line drawing of Robert and Aminta at the death-bed of Mrs. Armstrong is no great adornment to Lord Ormont and his Aminta, while Mr. Sauber's plate to "The Tale of Chloe" is distinctly conventional, illustrating the lines:

"Fear not, pretty maiden," he said, with a smile;

"And pray let me help you in crossing the stile."

She bobbed him a courtesy so lovely and smart,

It shot like an arrow and fixed in his heart.

Unique among the illustrations of Meredith's poetry is the edition of "Jump-to-Glory Jane" produced by the late Harry Quilter in 1892. This contains forty-four designs invented, drawn and written by Lawrence Housman. The mis-spelling of Mr. Housman's name, which is printed in bold type on the title page and occurs again in the text, cannot have been a printer's error; but whether Mr. Laurence Housman used to spell his name with a "w" I cannot say. That is a minor point. Here the pictures are the thing, rather than the poem or the critical notes wherewith the editor prefaced the little work.

The poem itself was first published in the Universal Review, in 1889, and the editor would seem to have endeavoured in vain to get an artist to illustrate it suitably there, but having determined that it was capable of imaginative treatment in black and white he carried out his idea a year or two later by entrusting Mr. Housman, then a young and promising artist, with the work. He had suggested Mr. Linley Sambourne to Meredith in 1889, as the right man to do the drawings, and the poet replied: "Sambourne is excellent for Punch, he might hit the mean. Whoever does it should be warned against giving burlesque outlines. "For some reason or other Mr. Sambourne could not undertake it and Mr. Bernard Partridge was next applied to, but "his heart failed him" — he was surely the last man to do the drawings, so that his heart did not misguide him! — and consequently the poem first appeared without illustrations. Later when Mr. Housman undertook the commission, the artist, whose imaginative touch is seen in all his [378/79] line work, as it has later found expression in both prose and verse, complete the series.

Here was the man for the work: he had just that restrained notion of the comic which blends into the weird, the imaginative, the mystic, the spiritual, and is so rare among artists. Mr. Sambourne would certainly not have made a success of the drawings, had he been so misguided as to undertake them. Mr. Housman did, so far as success was attainable.

Three illustrations by Laurence Housman for "Jump to Glory Jane." Left to right: (a) "Her first was Winny Earnes...." (b) "Those flies of boys disturbed them sore." (c) "Her end was beautiful."

Quilter very frankly criticises the drawings. "They are not perfect by any means," he says, "and in many points open to serious criticism, but the root of the matter is in them — they have the rare qualities of imagination and sympathy, and from the technical point of view, they show that this artist has only to work to become an admirable designer." They fail only in certain details of pen-work, it seems to me, indicating no weakness of the artist, but an in acquaintance with the limitations of process engraving, then less advanced than it is to-day, and the technique of which he speedily mastered.

As imaginative pictorial presentments of the poem they are wholly admirable. The "wistful eyes, in a touching but bony face," and the whole gaunt, pathetic figure of Jane are successfully realised. The subtle suggestion of the stained-glass saint in the jumping figure of Jane, as in the plate, showing the prophetess appearing before her first convert, "Winny Earnes, a kind of woman not to dance inclined," has a firmness and confidence of line which would have strengthened some of the other designs, while that illustrating the verse "Those flies of boys disturbed them sore,"" has a quaint touch of friendly humour in the figure of Daddy Green, in whom the boys seem chiefly interested.

Mr. Housman's drawings are certainly among the most interesting of all the Meredith illustrations, and one cannot but think that they must have had the approval of the poet himself, as they fully conform to the lines he had laid down for the illustrating of the poem, being charged with quiet but sympathetic satire of the religious mania he sought to expose, and never remotely leaning to burlesque: indeed, there is pity in them, as in the poem, and pity, as a rule, is no friend of satire.

Two of William Hyde's photogravure illustrations for Meredith's nature poetry.

To Mr. William Hyde are due some of the finest of recent illustrations to Meredith, and these entirely of nature scenes. Mr. Hyde's work is of a rare quality in nature-feeling and repose, with [379/80] just that touch of indefiniteness that leaves us still with a little of the mystery to colour our vision of the scene, so that no better illustrator of Meredith's poems could be imagined. The collection of Nature Poems of George Meredith, published in 1898, with twenty full-page pictures in photogravure and an etched frontispiece by Mr. Hyde, is a real artistic treasure. For the two volumes of poems in the edition of 1898, Mr. Hyde drew the Chalet and Flint Cottage, and London Bridge as the frontispiece to One of Our Conquerors. The view of Oxshott Woods which adorns Sandra Belloni is also, I suspect, by Mr. Hyde, and he too may have drawn "Off the Needles" which accompanies Beauchamp's Career, but if so it is not quite in his usual style. There is a pretty wash drawing of Queen Anne's Farm to Rhoda Fleming and "The Old Weir," finely suggestive of the romantic quietude of the scene, to Richard Feverel, both by Mr. Harrison Miller, while Mr. Maxse Meredith contributes a dainty little line drawing of "Crossways Farm" to Diana, and there is a fine sunny wash of La Scala by Mr. Edward Thornton as frontispiece to Vittoria. For The Amazing Marriage a photographic view of a scene in Carinthia is thought sufficient, and a dignified, virile bust of Lassalle, evidently of German origin, is given as frontispiece to The Tragic Comedians. One of the earliest and best of all the illustrations to Meredith is included in the "New Popular Edition." This is F. Sandys's well-known picture of "Bhanavar among the Serpents of Lake Karatis," a fine decorative work which was first engraved on steel for the 1865 edition of Shagpat and the original of which in oils was exhibited at the Royal Acadamy show of English painters some years ago.

Frederick Sandys's Bhanavar the Beautiful (1894).

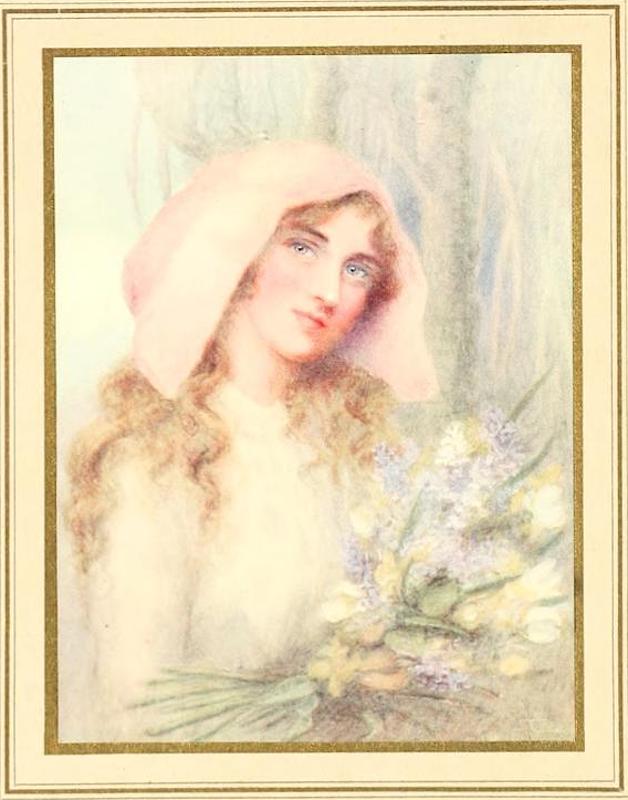

In the autumn of 1908 a most noteworthy addition was made to the gallery of Meredith illustrations in the shape of Mr. Herbert Bedford's fine series of miniature portraits of "Meredith Heroines," exhibited at the Dore Gallery from October 23 to November 18. Mr. Bedford takes eminent rank among the illustrators of Meredith by virtue of these exquisite little paintings on ivory. For many years the thoughts of this well-known miniaturist had been so engaged with Meredith's womenfolk that he set himself the delight- ful task of searching out fair sitters who already possessed many of the physical charms of the heroines, determined to interpret in a series of beautiful ivories the Meredithian women who had most captured his fancy. His paintings are thus idealised portraits of actual ladies who, more or less, "fill the bill" of the novelist in the [380/81] matter of good looks, and few who saw Mr. Bedford's exhibition will deny the genuine feeling for character which he displays in his interpretation of these famous figures of the novelist's imagination.

In all, fifteen subjects have been exhibited by the artist, and where the quality of all is so even it is not easy to indicate preferences. His Lucy is certainly worthy of Ripton Thompson's "She's an angel!" and Mrs. Mount is admirably caught, in a way to justify her creator's declamation that "she could read men with one quiver of her half-closed eyelashes." If anything, I prefer Keene's Louisa, Countess de Saldar — although Keene so often failed in depicting women — to Mr. Bedford's. There is, of course, no real comparison of the two pictures; Keene's easy, confident pencil lines against Mr. Bedford's meticulous brush and colours. But I feel that Mr. Bedford's is too charming a face — it is a little gem of painting, the black of the Portuguese head-dress against the delicate flesh tints being perfectly contrived — too charming for that lady, whose affectation of indolence is so happily suggested by Keene. On the other hand, Mr. Bedford's Rose Jocelyn is as successful as Keene's is stodgy and ungraceful, while his Caroline makes one almost willing to agree with George Uploft, when he said of her, "The handsomest gal, I think, I ever saw!"

Three of Meredith's heroines, as depicted by Herbert Bedford. Left to right: (a) Lucy, from The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. (b) Rose Jocelyn, from Evan Harrington. (c) Diana from Diana of the Crossroads.

From The Egoist Mr. Bedford has taken, of course, Clara and Laetitia, and he is more successful, I fancy, with the latter, more to the book, that is to say, giving us some real hint of the character, for which he has chosen the words of Mrs. Mountstuart Jenkinson, "Here she comes with a romantic tale on her eyelashes." This Mr. Bedford has used as his text and applied admirably. But Clara seems to me too literally the "dainty rogue in porcelain," with a shortage of character in her girlishly pretty face. The three subjects from Rhoda Fleming, however, are all brilliantly successful. Dahlia is a blonde beauty of the freshest, and caught in that moment when, before her mirror, she herself has said, "There were times when it is quite true I thought myself a Princess." Rhoda, if she has a fault in Mr. Bedford's hands, seems too capable of sympathy, she lacks suggestion of hardness, but certainly "she has a steadfast look in her face." Mrs. Lovell, fair and fascinating, is as surely the imaged figure of Meredith's imagination as Diana, with her dark hair and dignified mien is curiously suggestive both of the fact and the fiction of that character. The serene-minded Lady Dunstane companions Diana, and from The Amazing Marriage [381/82] Mr. Bedford has chosen Carinthia, Livia, and Henrietta, which complete the series.

I believe that he contemplates pursuing his most praiseworthy labours, to the end that he may produce a gallery of similar miniatures representative of the leading feminine characters in all the novels. Whether this be achieved or not, Mr. Bedford has already done a very notable work, which gives him an unique place among the illustrators of Meredith.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Hammerton, J. A. (Sir). George Meredith in Anecdote and Criticism. London: Grant Richards; New York: M. Kennerley, 1909. Internet Archive, from a book in the New York Public Library. Web. 16 April 2023.

[Illustration source] Meredith, George. Nature Poems of George Meredith, illustrated by Williamhyde. London: Constable, 1907. British Library, system 00246306.

Created 20 April 2023