n the opening pages of The Picture of Dorian Gray, we are told that ‘There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about’ (p.6). Oscar Wilde’s observation had special currency in the social circles of the 1890s, but his comment might also be applied to the fate of many Victorian artists who enjoyed a considerable reputation in their own time and are now almost entirely forgotten. One such figure is the Scottish designer, William Ralston (1841–1911). Ralston, a household name at the end of the century, was a toiler in art of prodigious productivity and unusual versatility; though only minimally trained he ranged across the disciplines of painting and illustration, photography and the design of book-covers.

Ralston produced celebrated work as a cartoonist for Punch and as a satirist and social commentator for The Graphic. These engagements ran from 1870 until the closure of The Graphic in 1908 and he was concurrently involved in the family’s photographic business based in Glasgow, where he took hundreds of portraits. Other work included popular comic books for children such as The Demon Cat[1889] and travelogues of witty observations, notably K.B. and D.A.’s Yachting Holiday [1894]. These works have largely slipped into obscurity, and it is only recently that his bindings have been rescued from misattribution by the pioneering research of Gregory Jones and Jane Brown (2003).

The variety of Ralston’s work suggests fragmentariness, yet it would be more accurate to describe it as an homogenous whole. Able to move seamlessly between photography and art, he embodied the virtues of the Victorian polymath. To some extent his activities co-existed in a symbiotic relationship: his topical sketches for The Graphic reflect a photographer’s eye for the immediacy of the scene and his capacity for pattern-making, so evident in his comic-strip versions of the everyday, is clearly linked to the abstractions of his earliest book-covers. This cross-fertilization had the added benefit of enhancing his reputation. In Glasgow he was fêted as a local celebrity, the photographer who was known across Britain (Kirkintilloch Herald, 1890, p.8) as a famous artist. His status as a designer working for two of the most popular journals of the time was undoubtedly a boon, generating earnings as the celebrated cartoonist in black and white took the latest photograph for the family parlour. These connections are aspects of a complicated life

Life and Career

William Ralston was born in 1841, a date often given incorrectly as 1848, in Milton, a small industrial village near Dumbarton and about twenty miles to the north-west of Glasgow. Ralston was reticent about his family background: he told the art critic J.A. Hammerton that his background was ‘poor but honest’ (p.94) and he refused to provide biographical material for another commentator, Grant Reid (MS. correspondence, Edinburgh University Library).

However, his background was not as humble as he implied. Originally artisanal with a puritanical belief in the sort of self-improvement promoted by the Kirk, the family was of aspirational stock, a philosophy embodied by Ralston’s father, Peter Ralston. Ralston senior was a pattern designer for calico printers in Milton and Glasgow and seems to have had some advanced training in art and design. In 1856 he set himself up as a photographer in Glasgow; the business was slow to establish itself and was subject to the usual vagaries. Such ventures were always perilous in mid-Victorian Britain and although we might expect his son to have a secure place at home, this was not the case. On the contrary, William’s early years were characterized by struggle and change. The period is summarised by Jones and Brown, who explain how:

William left the Old Normal School at the age of 12 to earn his living, first as a cabin-boy on a Clyde steamer, then in a Glasgow warehouse [while] also assisting his father. Suspected of delicate health at the age of 17, he was sent to Australia to benefit from the climate, leaving Greenock on the ship Chrystolite in November 1858 and arriving four months later in the recently established colony of Victoria. Australia was in the grip of a major gold rush and [he] worked for a while as a gold-digger. However, he does not seem to have made his fortune, and had to work also in a vineyard and for a photographer [p. 175].

In his absence his father’s business had picked up and on his return Ralston took charge of one of its two branches, producing a huge number of photographs, supervising others and acquiring a high level of technical proficiency. However, his ambitions were always in the direction of art rather than photography. As M.H. Spielmann astutely remarks, he was ‘a photographer by profession, but by taste and opportunity an artist’ (p.543).

To acquire the skills he needed he emulated his brother John, who was establishing himself as an artist and allowed his sibling to watch him as he worked. He was also, briefly, a part-time student at the Glasgow Art School (Jones and Brown, p.175). These activities took him some of the way, but like A. W. Bayes and others from constrained backgrounds, he was essentially self-taught. An avid sketcher, he learned the rudiments of comic draughtsmanship in pen and ink while experimenting with watercolour and oil. Ralston’s earliest work in black and white has not survived, but a series of slight watercolours painted in 1863 are preserved in the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. One is a rustic scene in the manner of George Morland and the others are seascapes; all are tentative, the work of an autodidact with potential.

During the period from 1865 to 1870 he developed his style and technical know-how by working for an unknown binder based in Glasgow where, it is suggested, he designed his first book-covers (Jones and Brown, p.176). At the same time he sent speculative drawings to Punch and The Graphic, a strategy which ultimately bore fruit in the form of permanent work. He quickly established himself as a regular and contributed some hundreds of drawings to the pages of both magazines, where they can be identified by his name and by his monogram, ‘WR’. Described by Spielmann as having plenty of ironic Glaswegian ‘wut’ (p. 543) and by James Caw as ‘primarily a comic man’ (p.295), Ralston’s was a new comedic voice which enlivened the periodicals’ columns; it was also put to good use in juveniles, notably Houp-La (1889), The Story of the Jovial Elephant [1905] and the most enduring of his works in this genre, Tippoo: a Tale of a Tiger [1886]. These slight publications were enhanced with a cover designed by Ralston, who continued in parallel his work as a photographer.

Tireless to the end, he died in London, aged 70, on 26 October 1911 (Jones and Brown, p.176), after suffering a stroke. Rising from a relatively humble background, his career was another example of the self-made artist at work, displaying a Smilesian capacity for social improvement that he shared with his remarkable contemporaries, Charles Bennett, A. W. Bayes, Robert Barnes and William Small.

Ralston as an Illustrator: Working for Punch, 1871–86

Ralston gained employment at Punch by sending examples of his work to the magazine’s engraver, Joseph Swain. Swain ‘discovered’ his talent and handed the material to the editor, Shirley Brooks, who engaged the artist for the opening months of 1871. At this point, some of his drawings were accepted and some rejected; a letter from Brooks to Percival Leigh (23 August 1871) suggests that the editor was a scrupulous judge and Ralston’s beginnings at the paper were low-key and tenuous (Layard, p.475). But this arrangement was quickly consolidated and he was rewarded with the break-through he was looking for: aged 31 and about to be married, his perseverance was recognized. This arrangement did not involve a re-location and he continued to work (until 1875) at the Glasgow photographic studio while sending his drawings, which were always on paper in readiness for engraving, through the post. However, the psychological impact of his new job was considerable; going to work in the photographic studio as usual, with no contact with his Punch colleagues except through the medium of correspondence, he told Hammerton how he had ‘tried to look unconscious of my greatness and mentally determined that it would make no difference to my bearing’ (p. 93). Constrained by his upbringing in the Kirk and severely self-disciplined, he was seemingly incapable of flamboyance – a limitation strangely at odds with the humour of his cartoons.

Two of Ralston’s Punch cartoons. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Nevertheless, Ralston went on to work for Punch for about ten years, contributing in that time 227 drawings made up of initials and satirical cartoons (Spielmann, p.543). They were mainly of generic comedy scenes, but the artist made a space for himself by exploiting his status as a sort of foreign correspondent, providing a novel perspective on middle-class mores by viewing them from a distinctly Scottish point of view; working for a metropolitan journal, he added what at the time was regarded as a provincial flavour. A good example is The Campbells are Coming, one of his earliest designs (28 June 1871, p.31). This shows a couple of swells, one of them dressed in an elaborate plaid which is said to be ‘loyal’ in acknowledgement of the Queen’s Scottish connection, but is ridiculously affected at a time when Scottish ornaments and costumes were a fad.Sunny Memories of a Foreign Lands (15 March 1873, p. 113) maps a parallel vein of humour and much of his work ridicules both Scots and Englishmen; as Alex Leese explains, Ralston ‘regularly drew’:

stereotypes and clichés of the Scottish character to present a satirical portrait of his fellow countrymen [and] regularly poked fun at the English, such as the overbearing southerners visiting Scotland for their holidays and [suffering] their comeuppance at the hands of a quick-witted Scot [p.14].

Some of his illustrations are more conventional and seem in many ways a revival of the sort of situational comedy pioneered by John Leech in the 1840s. Mark Tapley Junior (14 February 1871, p.44) exemplifies the approach. It shows Tapley in the shadow of his father’s gigantic protuberant stomach; Tapley elder is a type closely modelled on Leech’s portraits of the unsophisticated middle-classes, and the whole scene, with its enclosed spaces and tightly-focused situation, is clearly influenced by the earlier artist’s style. Ralston’s work was in this sense slightly old-fashioned and it is interesting that Brooks thought there was still a demand for the humour of caricature. Ralston’s comedy was very different from George Du Maurier’s elegant observations and John Tenniel’s neo-classical absurdities. Always small scale, with few of his drawings being more than quarter-page, his illustrations create a comedic world of over-dressed dandies and red-faced paters at the middle-class fireside.

Though largely unadventurous, Ralston’s designs are remarkably accomplished. The artist’s lack of formal training is concealed by their physical and conceptual smallness and each delivers a tightly focused, comedic situation in which laughter is invoked in the form of a passing glimpse of bourgeois life. In the words of Hammerton, ‘Ralston’s drawing is always accurate, his portraiture charged with character and humorous expression, his lines vigorous and purposeful’ (p.98).

His association with Punch came to an end when the editor died in 1886. Ralston had had a close relationship with Brooks and did not want to serve under new management.

Ralston, The Graphic, and Books at the End of the Century

Ralston’s contributions to Punch were matched by parallel work in The Graphic, which was set up in 1869 under the direction of W.T. Thomas. Thomas selected for his team some of the outstanding artists of the day and Ralston’s appointment placed him in the forefront of British talent. His earliest designs were produced in Scotland, but in 1875 he was offered a permanent position and moved to London, only moving back to Glasgow when his father died at the end of the eighties and he was forced once again to work as a photographer while contributing illustrations at a distance.

Ralston occupied an unusual position at the Graphic, a magazine primarily known for its social realism. Hubert Herkomer, William Small and Frank Holl provided harsh journalistic images of mid and late Victorian poverty, but Ralston moderated the severity of their gloomy cuts in black and white with humorous scenes, often in colour, of foreign events, domestic farce and the middle-classes at play, with a special interest in sport.

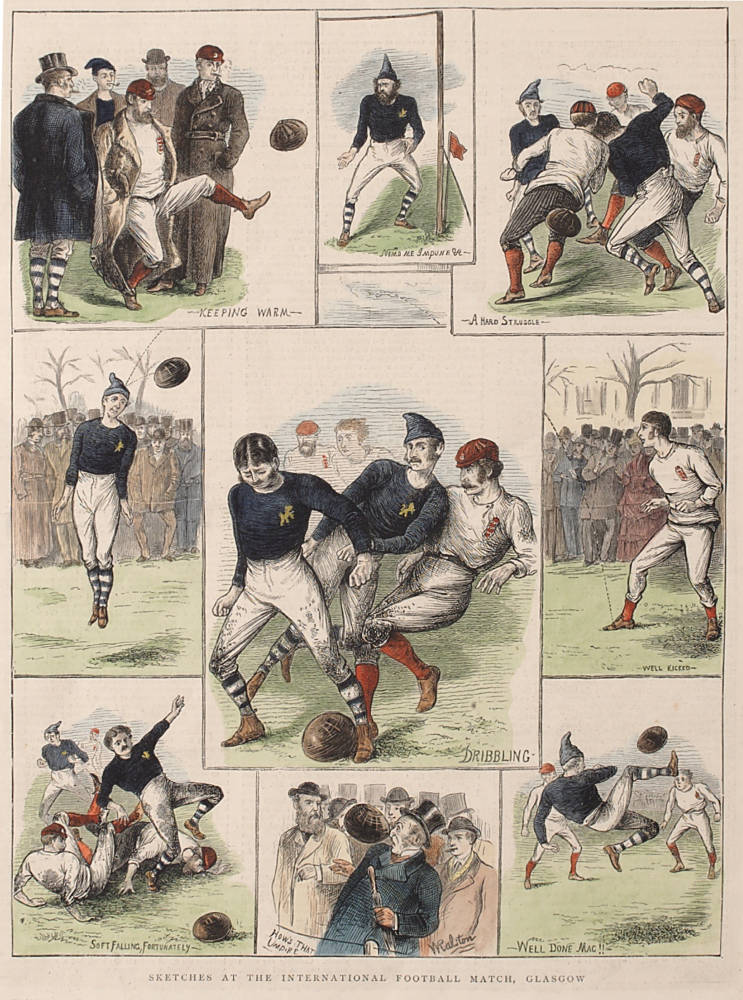

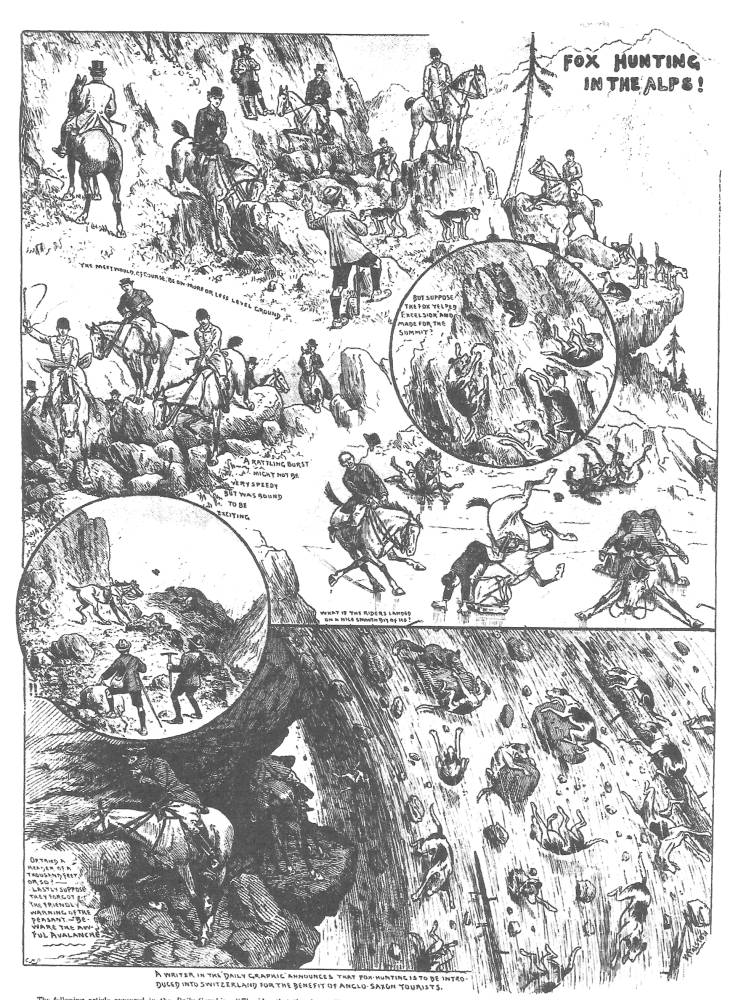

Two of Ralston’s cartoons about sport, one humorous, the other satirical. Left: Sketches at the International Football Match, Glasgow. Right: Fox Hunting in the Alps [as a way to attract more English tourists]. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

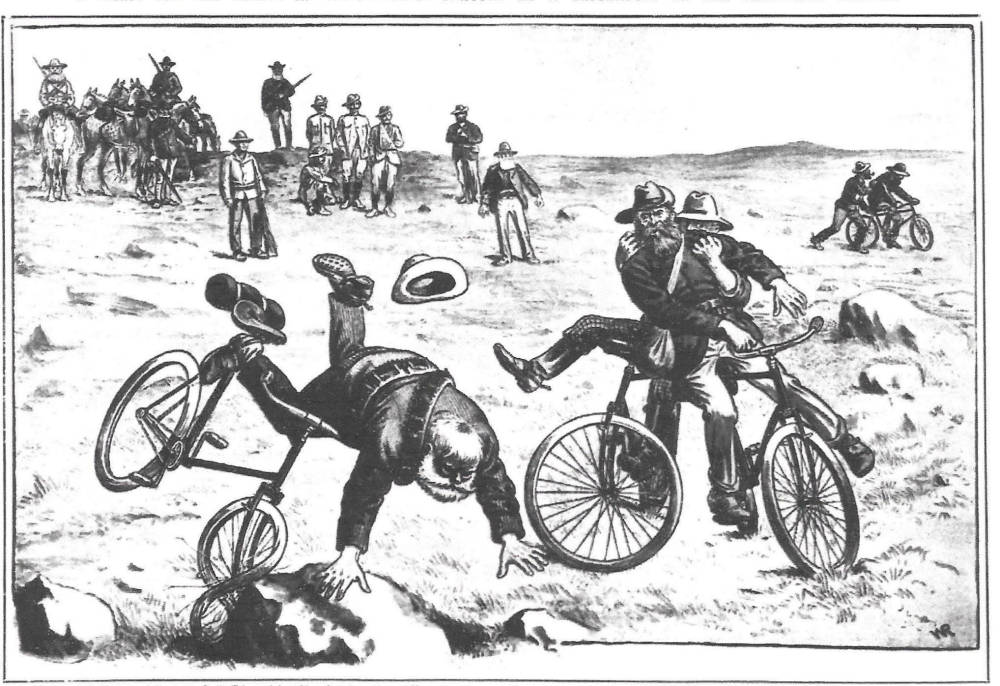

Some of these must have been based on written descriptions, presenting purely imaginary visualizations as if they were visual reportage. His approach is notably deployed in designs showing scenes in India and Africa and is applied with no sense of incongruity to events taking place in Britain, even those on the streets of the capital. Anything but an on-the-spot journalist, Ralston’s images are essentially comical interpretations of topical events after they were reported – an approach typical of Punch but not of the urban imagery of Small and Herkomer. A late example of this type of farce is Humours of the War. Boers Trying their Newly Captured Mounts (16 November 1901, p.638). Essentially propaganda which counters the enemy’s military successes, the image shows the Boers as hirsute buffoons trying to master bicycles as they career over rocks in a barren landscape; like all enemies of the Empire, they are shown as children trying to upset the authority of their British elders.

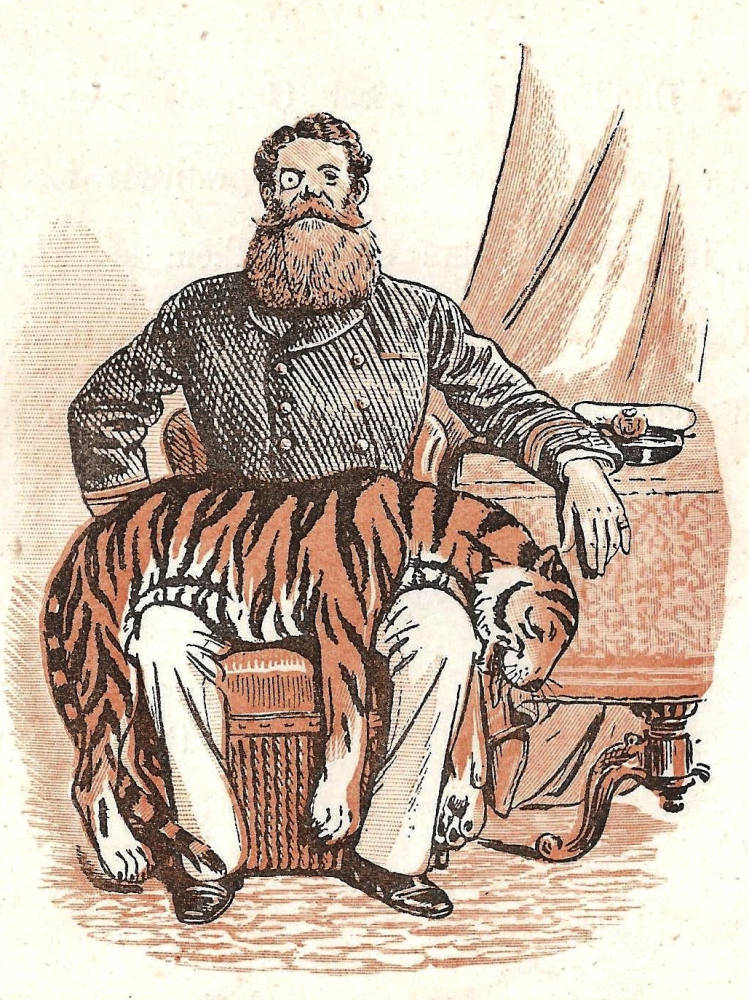

Two of Ralston’s cartoons that reflect upon the British empire. Left: Tipoo. What happens when one brings an Indian tiger home to England. Right: Boers Trying their Newly Captured Mounts — a work of the same kind of false sense of superiority that one sees in cartoons before the Crimean War. In this case the Boers took an English-made weapon rejected by the army and used it to inflict devastating losses upon British forces. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Other visual re-interpretations must have been based – appropriately enough – on photographs, and Ralston’s designs for The Graphic occupy a suggestive space between photography and drawing. He made an important contribution to the development of what has been called the ‘picture-story genre’ (Smolderen, p.92), a format in which illustrations are ‘arranged’ on ‘the page as if they were leaves pinned on a board’ (p.89), or calotypes in a vertical montage. His images are organized sequentially as captured moments in time as if the frames were photographs and in his later designs the overall effect, with its emphasis on showing stages in the narrative, is closely linked to the new photographic medium of film. Fox Hunting in the Alps (The Graphic, 20 April 1901, p.560) could easily be a storyboard for an early cinema-montage, and so could The Influence of Christmas Theatricals (3 January 1903, p.21).

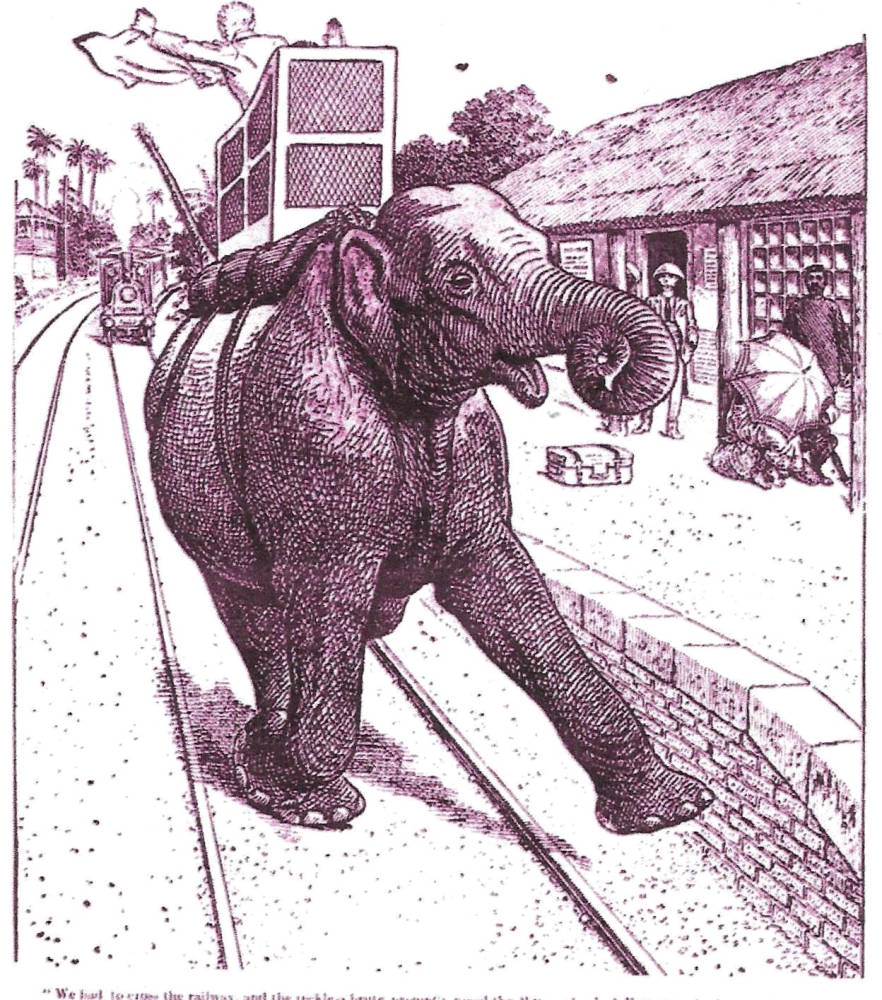

Left: The Jovial Elephant. Middle: Tippoo at Home. Right: Tippoo creating mayhem. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Ralston’s contributions to Punch were mainly conservative, relying on well-established graphic conventions, but in his work for the Graphic he made a significant contribution to new ways of presenting narratives as images to be scanned as part of a flow of pictorial information – a development that prefigures the rapid production and consumption of visual signs in early Modernism and is also instrumental, rather more prosaically, in the development of comics and graphic novels.

Ralston was producing this type of composition almost as soon as he joined the magazine. Perhaps his most celebrated image was a representation of the first official football (soccer) match between England and Scotland in The Graphic for 14 December 1872 (p.4). Football was then regarded as a hobby worthy of gentlemen, if not on the same terms as golf, polo, fishing and croquet. Though inspired entirely by a written report and appearing two weeks after the event, Ralston’s montage of nine episodes gives dynamic form to the struggle and competitiveness of a clash between the ‘auld enemies’. In a detailed essay, Alex Leese explores the illustration’s iconography and significance as a historical document, but for most viewers the lasting impression must surely have been one of intense immediacy, of action barely contained in a series of frames which, as Leese remarks, creates the effect of a ‘composition of incidental scenes … recalling the layout of a cluttered scrapbook or photograph album’ (p.12).

This capacity to represent the contemporary in apparently spontaneous forms was the mainstay of Ralston’s work at The Graphic. Images of the Boer War, holidaying abroad, the ever greater scale of Cunard ships, sporting events, the vicissitudes of the servants and the perpetual rivalry between Scotland and England are his primary themes. His contributions diminished when he returned to Glasgow at the end of the eighties, but he began a new venture in the form of cartoon books.

Several of these are juveniles involving mock-bestiaries: Tippo: A Tale of a Tiger [1886], The Demon Cat (1889) and The Story of the Jovial Elephant (1905). Each is a spirited burlesque with the main emphasis, as in the drawings for Punch, on situational comedy. Another comedic strand is provided in the form of calculated incongruity; in The Demon Cat, for instance, the feline is shown in amusingly inaccessible (but not impossible) positions on board a ship, while in Tippoo the pet tiger has the consistency of a floppy toy. In Tippoo and the Jovial Elephant colour is used to decorative effect, and all of his books for children can be linked to the polychromatic juveniles of the eighties and nineties, especially those of Randolph Caldecott. Ralston’s humorous draughtsmanship was further deployed in the production of cartoon books for adults. Sports for Limited Purses[1899], North Again (1899) and Yachting Holiday [1896] exemplify his manner for adults. Presented, once again, as albums of droll scenes and farcical misunderstandings, they represent the final development of the artist’s mildly satirical humour.

Related material

Acknowledgement

I am indebted to Professor Paul Goldman, who read the first draft of this essay.

Primary sources: archive and manuscript material

Ralston, William, MSS. Letters to John Reid. Edinburgh University Library.

Ralston, William. Photographs by Ralston & Sons, The Mitchell Library, Glasgow, and The National Portrait Gallery, London.

Ralston, William. Watercolours. The National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Printed works

Cole, C.W., and Ralston, William. The Demon Cat, a Naval Melodrama. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co, 1889.

Cole, C.W., and Ralston, William. Tippoo: a Tale of a Tiger. London: George Routledge, 1886.

Golden Thoughts from Golden Fountains. With a cloth binding designed by Ralston. London: Frederick Warne [1868].

The Graphic, 1870–1908.

The Poetical Works of Henry Kirke White. With a cloth binding designed by Ralston. London: George Routledge, 1867.

Punch, 1871–86.

Ralston, William. K.B. and D.A. North Again: Golfing this Time. London: Simpkin, Marshall, (1894.)

Ralston, William. K.B. and D.A.’s Yachting Holiday. London: Simpkin Marshall [1894].

Ralston, William. Sports for Limited Purses. Glasgow: Bryce [1899].

Ralston, William. The Story of the Jovial Elephant. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1905.

Summer Tours in Scotland. Illustrated by William Ralston. Glasgow: Sinclair, 1901.

Winter, J.S. Houp-La. Illustrated by and with a binding by William Ralston. New York: Frederick Warne, 1889.

Secondary sources

‘Advertisement.’ Dundee Evening Telegraph, 8 June 1901:3.

‘Advertisment.’ The Hamilton Advertiser, 16 November 1867:4.

‘Advertisment.’ The Kirkintilloch Herald, 21 May 1891: 8.

Caw, James L. Scottish Painting, Past and Present. Edinburgh: Jack, 1908.

Hammerton, John Alexander. Humourists of the Pencil. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1905.

Jarvis, Simon. High Victorian Design. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1983.

Jones, Gregory V. and Brown, Jane E. ‘Victorian Binding Designer WR: William Ralston (1841–1911), not William Rogers.’ The Book Collector 52 (2): 171–198.

King, Edmund. Victorian Decorated Trade Bindings, 1830 –1880. London: The British Library, 2003.

Layard, G.S. A Great ‘Punch’ Editor, being the Life, Letters, and Diaries of Shirley Brooks. London: Pitman, 1907.

Leese, Alex. ‘Illustrating the Auld Enemies: Analysis of William Ralston’s Depiction of the First International Football Match between Scotland and England.’ Soccer and Society 16: 2 (2015) [online version].

Smolderen, Thierry. The Origins of Comics: from William Hogarth to Winsor McCay. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi [2014].

Spielmann, M. H. The History of Punch. London: Cassell, 1895.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. 1891; modern rpt. London: Bibliolis, 2010.

Last modified 9 October 2016