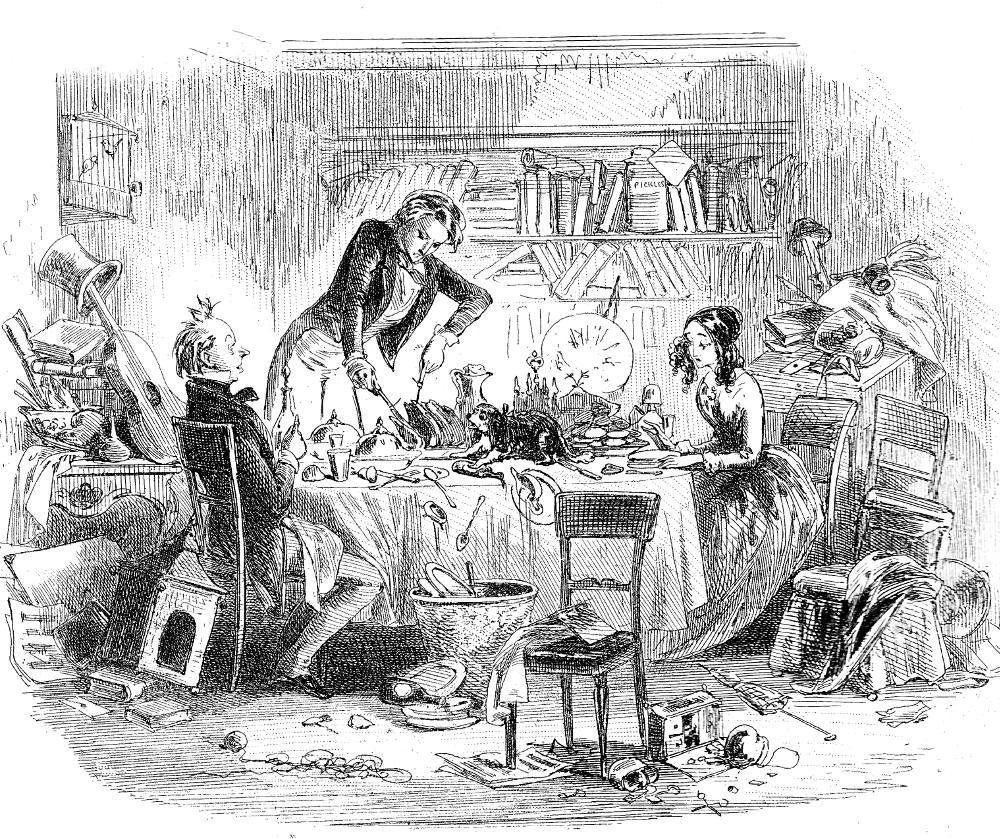

Our Housekeeping by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). July 1850 (Instalment No. 15). Steel etching. Illustration for Chapter XLIV, "Our Housekeeping," in Charles Dickens's David Copperfield. Source: Centenary Edition (1911), Volume Two, facing page 248. 10.2 x 13.3 cm (4 by 5 ¼ inches), vignetted.

Commentary

For the first illustration in the fifteenth monthly number, which was issued in July 1850 and comprises Chapters 44 through 46, Phiz demonstrates the unfortunate but comical consequences of David's marrying a "child-wife" with few domestic skills and less common sense. Once again, the observer and mediator is the good-hearted young attorney and newspaper writer Tommy Traddles (right), who watches his old school chum wrestling with a joint of lamb as the incorrigible Jip scampers across the dining table. According to J. A. Hammerton (1910), the moment that Phiz has realized is the following: "One of our first feats in the housekeeping way was a little dinner to Traddles" (vol. 2, 247).

In fact, Phiz has chosen one of the most entertaining — and for David utterly embarrassing — moments in the dinner as the host, failing in his attempt to carve a boiled leg of mutton, is about to abandon it and serve oysters instead:

There was another thing I could have wished; namely, that Jip had never been encouraged to walk about the table-cloth during dinner. I began to think there was something disorderly in his being there at all, even if he had not been in the habit of putting his foot in the salt or the melted-butter. On this occasion he seemed to think he was introduced expressly to keep Traddles at bay; and he barked at my old friend, and made short runs at his plate. . . . [vol. 2, 248]

The picture, like the others in Phiz's narrative-pictorial sequence which depict Tommy Traddles, emphasizes his unruly hair and chubby face. As is usual with Traddles, Phiz shows him in a social situation, as in Traddles makes a figure in parliament and I report him and Traddles and I, in conference with the Misses Spenlow, reacting with good humour to other characters in an interior setting. Once again, the scene occurs in David's residence, but we are no longer in his bachelor rooms in Buckingham Street, which have been the backdrop for We are disturbed in our cookery, My Aunt astonishes me, and Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt. Rather, in this view of David's residence we see neither a window nor the door (nor, for that matter, any sort of domestic order); the young couple are entombed, or perhaps caged in a confined space, the constriction reinforced by the impinging clutter; visual continuity with David's former residence is provided by the books (rear centre), now terribly jumbled, and the birdcage (left), whose occupants serve as a visual metaphor for the newly-weds established by Dickens himself early in the forty-fourth chapter: "I doubt whether two young birds could have known less about keeping house" (Vol. 2, 239-40), reflects David, reverting to the early days of their occupancy of the little cottage outside London that he had leased shortly before their marriage. Things in the dining-room are utterly chaotic, with the guest wedged into a corner next to Dora's guitar, David's hat, and Jip's pagoda:

The musical emblem becomes a guitar (the actual instrument played by Dora) in Our Housekeeping (ch. 44), rather unceremoniously used as a hatrack, and positioned beneath a caged pair of lovebirds who are now apparently quarreling, in contrast to those in an earlier plate. [Steig 122]

Another curious mistake is apparent in the interesting plate entitled "Our Housekeeping;" here David is seen struggling with a loin of mutton, whereas in the text the joint is distinctly described as a boiled leg of mutton. [Kitton 104]

Modern readers not accustomed to the Victorian tradition of the Sunday joint do not even register the discrepancy. Jan Rabb Cohen notes the prominence that Phiz has accorded to the jar labelled "PICKLES" which Phiz has prominently "displayed among the scattered books on the drawing-room shelf, [to] reveal the plight of their marriage" (104).

Although David and Dora can afford a cottage, albeit a small one, in a quiet suburban neighbourhood an easy walk from "Town" and Dr. Strong's, Dickens at David's age had rented two different sets of rooms at Furnival's Inn, London, from the period before his marriage to Catherine Hogarth until 1838, when the couple and their first child moved to Doughty Street, Holborn:

in December 1834 he moved with his younger brother, Frederick, into chambers at Furnival's Inn, He rented what was then known as a "three pair back" at what was then the not inconsiderable rent of £35 a year — three modest rooms, a cellar and a lumber room [Americans should read "storage area or attic"] in a not very prepossessing congeries of buildings which had been expressly built as chambers. It was a "good" address but somewhat gloomy. . . . [Ackroyd 161]

Apart from summer vacations in a cottage at the Kentish village of Chalk and another at Petersham, Charles and Catherine remained at their slightly more commodious and more expensive quarters at Furnival's to which Charles had shifted just before their wedding on 2 April 1836, made possible by his signing with publishers Chapman and Hall to write what would become The Pickwick Papers. Catherine's younger sister, Mary Scott Hogarth, visited frequently, and became resident after the birth of the Dickenses' first child on 6 January 1838. By the time of Mary's sudden death, aged seventeen, on 7 May 1838, she and her brother-in-law and her sister were living at 48 Doughty Street, now the Dickens House Museum, to which the Dickens had moved shortly after he began writing Oliver Twist, on 18 March 1837, a twelve-roomed house of four floors that dwarfs the little cottage in which David and Dora begin their married life. Thus, although the Dickenses' happy days early in their marriage may well be reflected in David Copperfield's "first married" chapters, there is nothing about the little Copperfield cottage that has much basis in the author's own residences in the early years of his relationship with Catherine Hogarth — and certainly neither a younger sister nor children intrude on the domestic infelicities of David and Dora.

The situation in Our Housekeeping is anarchic as David, in an early Victorian swallow-tail coat, cuts the meat, Traddles (ignoring Jip) tries to engage Dora in conversation, and Dora seems utterly unaware of either her husband or his guest. Cutlery falls off the table as Jip advances; clothing (largely feminine) is strewn about the room, and chairs are askew, as if the house is suffering an earth-quake. Sheet music, a parasol lying on the floor in the foreground, the spaniel on the dining-table, and a woman's work box tumbled open — reminiscent of the spilled sewing-box in Changes at home and thereby connecting David's mother and Dora — all point towards Dora as the source of the chaos. Despite what may appear to be random disorder, Phiz, as Kitton has noted, subjected the sketch of the illustration to editing, taking out "the frame of a mirror or picture . . . [that he had] introduced on the wall behind David" (105). Accordingly, we should assume that every detail that Phiz has included serves a purpose in creating the overall impression of "most admired disorder."

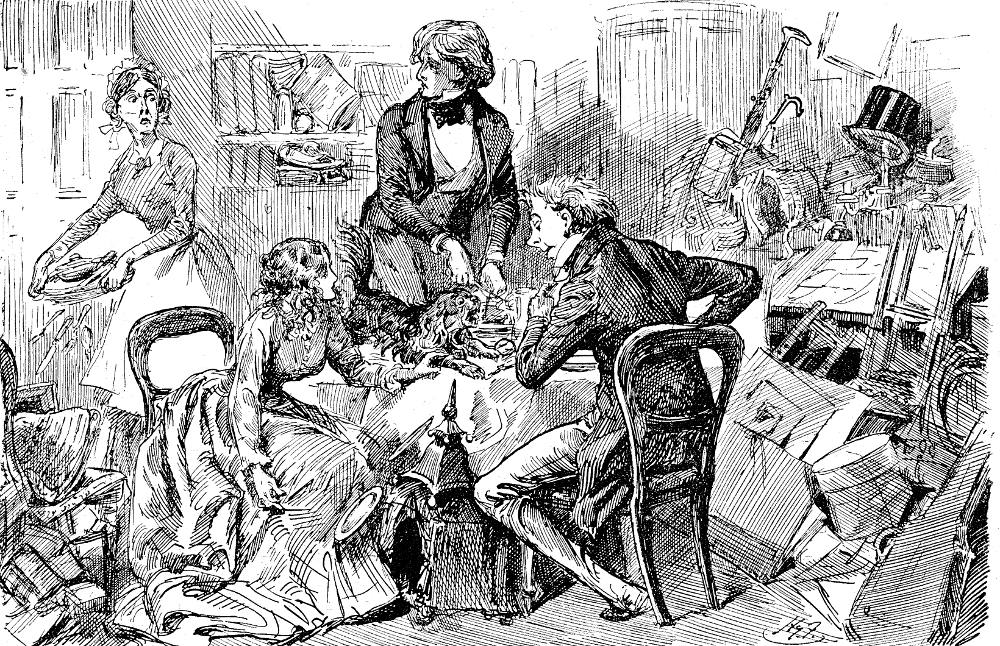

David learns the consequences of marrying Dora (1872 & 1910 Editions)

Left: Fred Barnard's Household Edition post-nuptial scene:

Related Resources

- The Remains of the Day: Death and Dying in Victorian Illustration

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 62 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's 29 lithographs for David Copperfield for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's six Player's Cigarette Card watercolours (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. 2 vols. London and New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

_______. The Personal History of David Copperfield. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. V.

_______. David Copperfield, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. III.

_______. The Personal History and Experiences of David Copperfield. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. X.

Hammerton, J. A., ed. The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the the Dickens Illustrations. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Created 25 January 2010 Last modified 16 March 2022