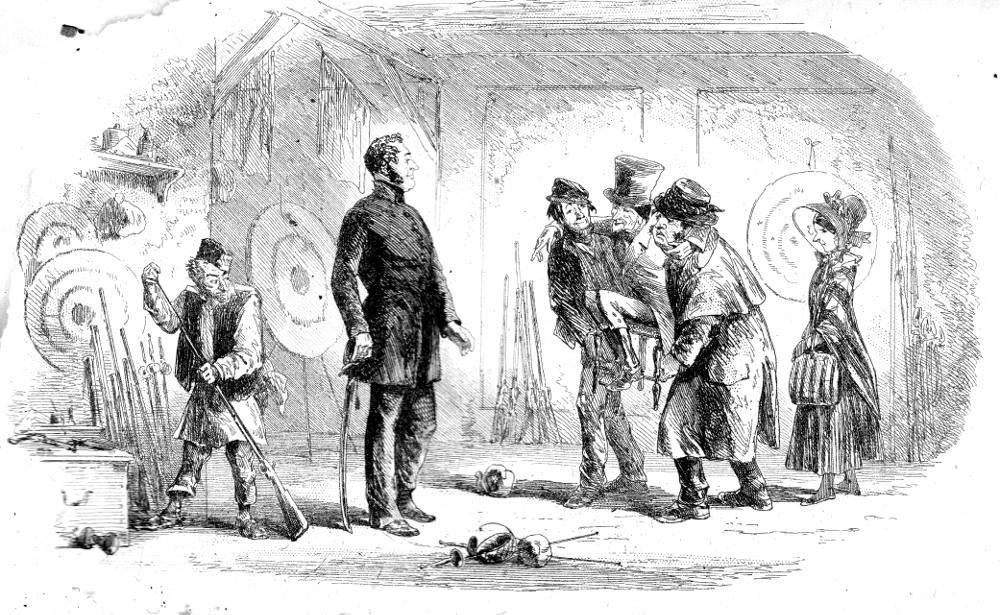

Visitors to the Shooting Gallery by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne) for Bleak House, facing p. 261 (Part Nine, November 1852: ch. 26, "Sharpshooters"). 4 ¼ x 6 ¾ inches (10.4 cm by 17 cm). For text illustrated, see below. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated

Master and man are . . . disturbed by footsteps in the passage, where they make an unusual sound, denoting the arrival of unusual company. These steps, advancing nearer and nearer to the gallery, bring into it a group at first sight scarcely reconcilable with any day in the year but the fifth of November.

It consists of a limp and ugly figure carried in a chair by two bearers and attended by a lean female with a face like a pinched mask, who might be expected immediately to recite the popular verses commemorative of the time when they did contrive to blow Old England up alive but for her keeping her lips tightly and defiantly closed as the chair is put down. At which point the figure in it gasping, "O Lord! Oh, dear me! I am shaken!" adds, "How de do, my dear friend, how de do?" Mr. George then descries, in the procession, the venerable Mr. Smallweed out for an airing, attended by his granddaughter Judy as body-guard.

"Mr. George, my dear friend," says Grandfather Smallweed, removing his right arm from the neck of one of his bearers, whom he has nearly throttled coming along, "how de do? You're surprised to see me, my dear friend."

"I should hardly have been more surprised to have seen your friend in the city," returns Mr. George.

"I am very seldom out," pants Mr. Smallweed. "I haven't been out for many months. It's inconvenient — and it comes expensive. But I longed so much to see you, my dear Mr. George. How de do, sir?" . . .

"So we got a hackney-cab, and put a chair in it, and just round the corner they lifted me out of the cab and into the chair, and carried me here that I might see my dear friend in his own establishment! This," says Grandfather Smallweed, alluding to the bearer, who has been in danger of strangulation and who withdraws adjusting his windpipe, "is the driver of the cab. He has nothing extra. It is by agreement included in his fare. This person," the other bearer, "we engaged in the street outside for a pint of beer. Which is twopence. Judy, give the person twopence. I was not sure you had a workman of your own here, my dear friend, or we needn't have employed this person." [Chapter XXVI, "Sharpshooters," 260-61; Project Gutenberg etext (see bibliography below)]

Commentary: At Trooper George's Shooting Gallery in Leicester Square

He is a swarthy brown man of fifty, well made, and good looking, with crisp dark hair, bright eyes, and a broad chest. His sinewy and powerful hands, as sunburnt as his face, have evidently been used to a pretty rough life. What is curious about him is that he sits forward on his chair as if he were, from long habit, allowing space for some dress or accoutrements that he has altogether laid aside. His step too is measured and heavy and would go well with a weighty clash and jingle of spurs. He is close-shaved now, but his mouth is set as if his upper lip had been for years familiar with a great moustache; and his manner of occasionally laying the open palm of his broad brown hand upon it is to the same effect. Altogether one might guess Mr. George to have been a trooper once upon a time. [Chapter XXI, "The Smallweed Family," ]

Part of the glue that binds the various subplots to the main plot of a Victorian novel is the backstories of such minor characters as Trooper George, the proprietor of a shooting gallery in Leicester Square. Since his business in London's entertainment centre is hardly booming, he can barely make the interest payments on his business loan from Grandfather Smallweed, a small-time loan-shark who, it turns out, is in league with the investigative attorney Tulkinghorn. The lawyer and his confederate are quite convinced that George Rouncewell can present them with a sample of the Nemo's handwriting, since before his descent into poverty and drug-addiction "Nemo" was Captain Hawdon, George's commanding officer. The writing sample would, Tulkinghorn expects, confirm the dead law-writer's true identity as Lady Dedlock's lover. Thus, Tulkinghorn through Smallweed applies to the hapless Trooper George to obtain that hand-writing sample which will enable Tulkinghorn to blackmail Lady Dedlock.Barnard has effectively reakised Dickens's description of the affable retired soldier:

>p>Almost as soon as Trooper George and his assistant, Phil Squod, have finished their breakfast, Grandfather Smallweed appears, carried by twe men (a cab-driver and a man from the street) and accompanied by his purse-holder, Judy, his granddaughter. The wheezy visitor approaches his subject obliquely, alternately praising George and expressing anxiety about Phil's accidentally discharging a firearm in his direction. Finally, gets to request, which involves the death of Captain Hawdon, that is, the drug-addict "Nemo." Smallweed suspects that George's former commander, Hawdon, was integrally involved in the case Jarndyce and Jarndyce, and he is determined to substantiate Nemo's true identity by having Mr. George's private papers examined by his associate. Smallweed presents the issue to Tropper George in a different light by suggesting that a sample of Hawdon's writing will prove whether he is dead.Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Bleak House

- Bleak House (homepage)

- Sir John Gilbert's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 4, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 61 illustrations for the Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's Illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910

Image scan and text by George P. Landow; additional text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Bradbury & Evans. Bouverie Street, 1853.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Project Gutenberg etext prepared by Donald Lainson, Toronto, Canada (charlie@idirect.com), with revision and corrections by Thomas Berger and Joseph E. Loewenstein, M.D. Seen 9 November 2007.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Created 12 November 2007 Last modified 7 March 2021