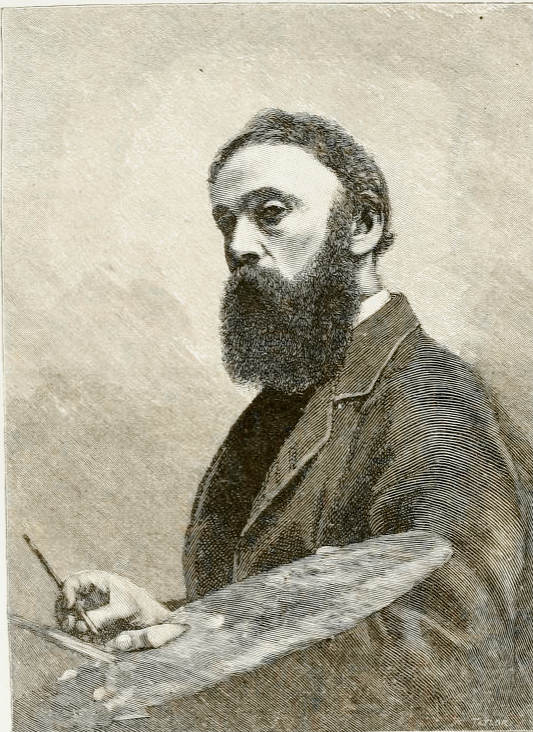

Albert Moore (1841–93) was one of the most important and influential neo-classicists of his generation, producing a series of paintings in which languid females, enveloped in an erotic atmosphere, are shown in decorative spaces. Offered in sharp contradiction to Victorian narrative paintings which demand to be read and tell a story, Moore’s designs are purely poetic, presenting images in which beauty itself is the subject. Classified as an important expression of Aestheticism, his paintings are neo-classical equivalents to the medievalist fantasies of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Though never an illustrator in the usual sense of the term, Moore also produced three wood-cuts for Milton’s “Ode on the Morning of Christ’s Nativity,” which was published by Nisbet in 1868, along with designs by William Small and E.M. Wimperis. Known only to specialists and locked away in one of the rarest gift-books of the period, these images, which are essentially a footnote in the history of mid-Victorian illustration, are sometimes described in dismissive terms. Forrest Reid is uncharacteristically hostile (1928), noting how the engravings are “too slight, too empty of content, to be of much intrinsic importance … in fact they can hardly be called illustrations at all. They are decorations, to be classed with some of Walter Crane’s work, though below his best” (p.204). But Reid overstates his case, for while not among the best in the style known as ‘The Sixties’, Moore’s illustrations deserve to be read in a more measured way. His three designs do have ‘intrinsic interest’, and should take their place among contemporary work.

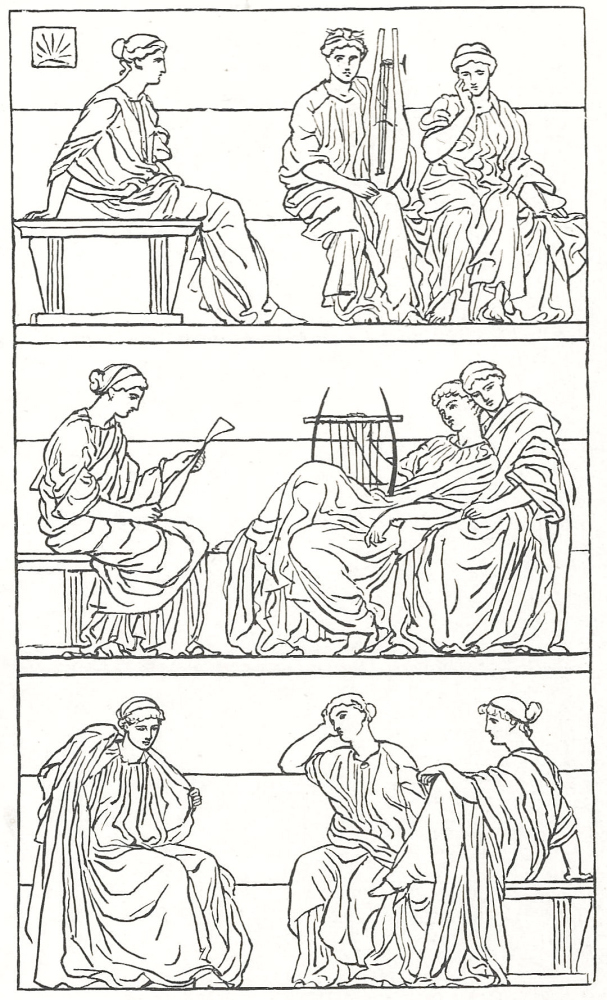

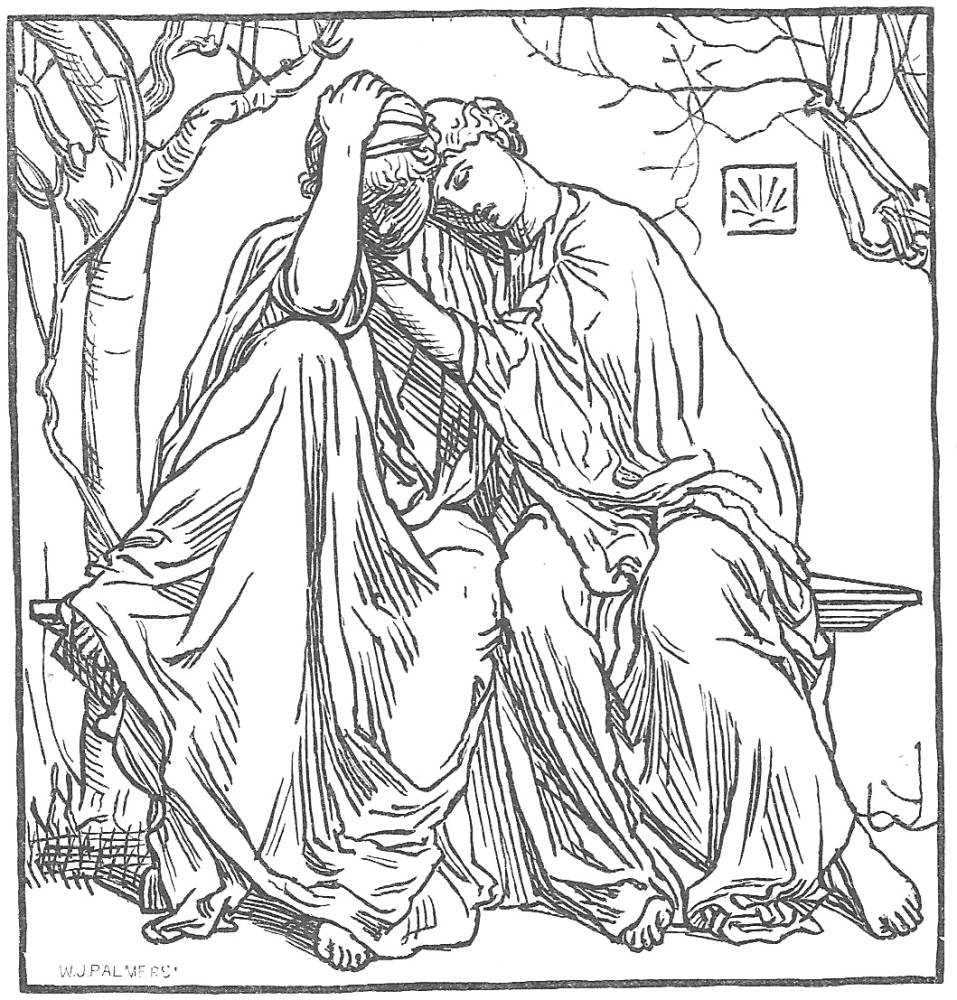

Left to right: (a) Nature. (b) The Muses. (c) The Nymphs [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

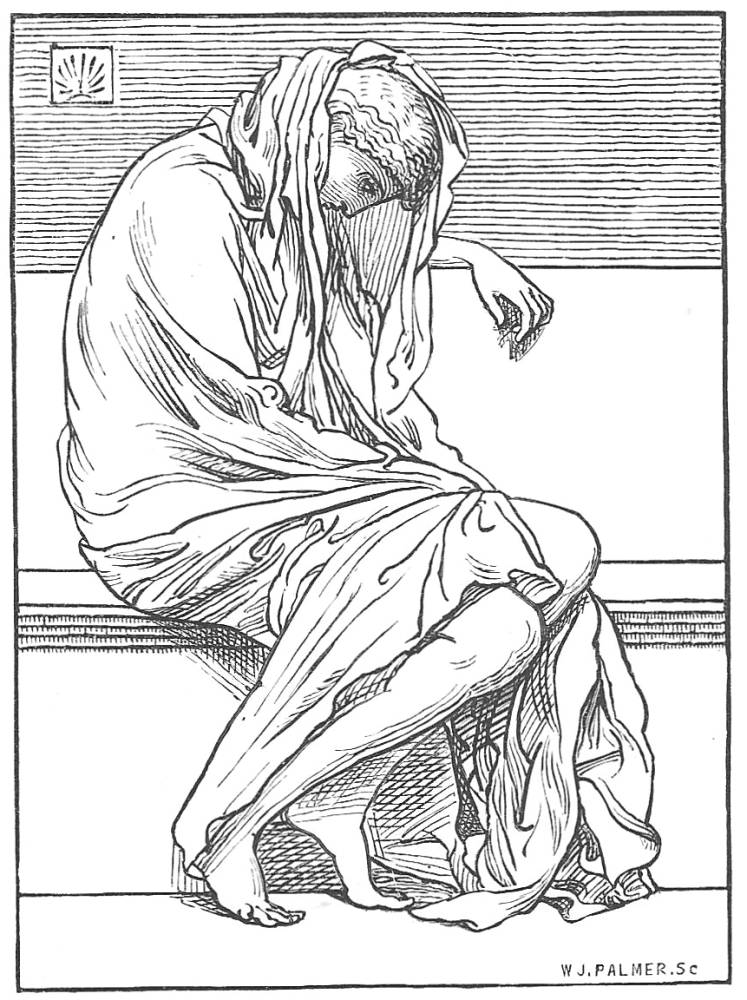

The subjects are abstract personifications, representing Nature (Ode, p.13), the Muses (p.28) and the Nymphs (p.35). Presented as Greek figures in the manner of Moore’s paintings, they visualize Milton’s classical language and provide the poem with a pictorial reference that complements the everyday scenes depicted by Small. In many ways a direct transfer from the artist’s images on canvas, the illustrations also provide a link with the epic ‘outline style’ developed by John Flaxman and

Yet they offer considerably more than the purely decorative values ascribed to them by Reid. On the contrary, they read as illustrations that expand and interpret the implications of the text. In the first design (p.13) we see a surprisingly emotional figure which visualises the notion of Nature moderated by her ‘awe’ at Christ’s birth, replacing her love for the ‘paramour’ sun (pp.12–14) with ‘sinful blame’. Pagan adoration is put away and Moore daringly shows this as a moment of loss, here symbolized in the form of a disconsolate beauty, her head bent forward in shame and sadness. The Muses are likewise uncomfortable, listless figures who assert a strong sense of decay. Most effective, though, is the final illustration of the Nymphs (p.35). This is a powerful representation of grief that goes well beyond the emotional range of Moore’s paintings and acts, once again, to foreground Milton’s exploration of melancholy.

Though fairly insubstantial, the images are consistently deployed as a means to highlight a key element in the writing. This purpose goes beyond the intense drama conveyed in Small’s designs and mediates between the poem’s realism and its mythologies. Overlooked and under-rated, Moore’s illustrations fulfil an important function.

Works Cited

Milton’s Hymn on Christ’s Nativity. London: James Nisbet, 1868.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Sixties. London: Faber & Gwyer, 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

Last modified 27 November 2013