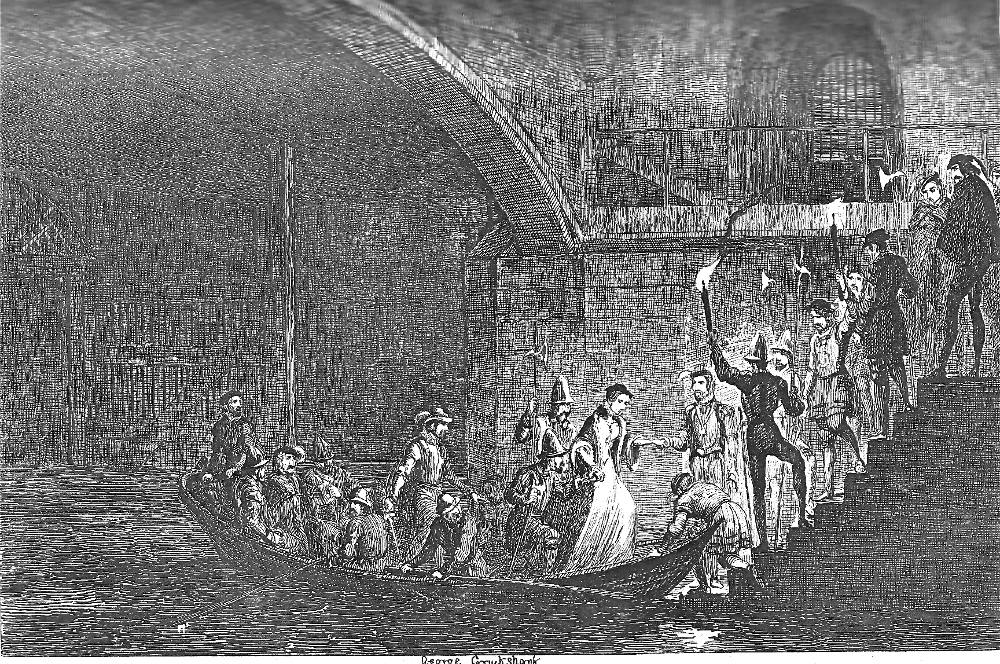

St. Thomas's, or Traitor's Tower, from the Thames — George Cruikshank. April 1840 number. Twentieth illustration (thirteenth wood-engraving) in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. 6.8 cm high by 9.0 cm wide, vignetted, p. 81. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

In this state she continued till they had shot London Bridge, and the first object upon which her gaze rested, when she opened her eyes, was the Tower.

Here again other harrowing recollections arose. How different was the present, from her former entrance into the fortress! Then a deafening roar of ordnance welcomed her. Then all she passed saluted her as Queen. Then drawbridges were lowered, gates opened, and each vied with the other to show her homage. Then a thousand guards attended her. Then allegiance was sworn — fidelity vowed — but how kept? Now all was changed. She was brought a prisoner to the scene of her former grandeur, unattended, unnoted.

Striving to banish these reflections, which, in spite of her efforts, obtruded themselves upon her, she strained her gaze to discover through the gloom the White Tower, but could discern nothing but a sombre mass like a thunder-cloud. St. Thomas's, or Traitor's Tower was, however, plainly distinguishable, as several armed men carrying flambeaux were stationed on its summit.

The boat was now challenged by the sentinels—merely as a matter of form, for its arrival was expected, — and almost before the answer could be returned by those on board, a wicket, composed of immense beams of wood, was opened, and the boat shot beneath the gloomy arch. Never had Jane experienced a feeling of such horror as now assailed her — and if she had been crossing the fabled Styx she could not have felt greater dread. Her blood seemed congealed within her veins as she gazed around. The lurid light of the torches fell upon the black dismal arch — upon the slimy walls, and upon the yet blacker tide. Nothing was heard but the sullen ripple of the water, for the men had ceased rowing, and the boat impelled by their former efforts soon struck against the steps. The shock recalled Jane to consciousness. Several armed figures bearing torches were now seen to descend the steps. The customary form of delivering the warrant, and receiving an acknowledgement for the bodies of the prisoners being gone through, Lord Clinton, who stood upon the lowest step, requested Jane to disembark. Summoning all her resolution, she arose, and giving her hand to the officer, who stood with a drawn sword beside her, was assisted by him and a warder to land. Lord Clinton received her as she set foot on the step. By his aid she slowly ascended the damp and slippery steps, at the summit of which, two personages were standing, whom she instantly recognised as Renard and De Noailles. The former regarded her with a smile of triumph, and said in a tone of bitter mockery as she passed him — "So — Epiphany is over. The Twelfth Day Queen has played her part."

"My lord," said Jane, turning disdainfully from him to Lord Clinton — "will it please you to conduct me to my lodging?" [Book One, Chapter 17, "In what manner Jane was brought back to the Tower of London," pp. 111-112]

The Climactic Canvas of Book One: Jane Brought under Guard to the Tower

Above: The relative tranquility of Cruikshank's wood-engraving of St. Thomas's and Traitor's Gate contrasts the high drama of the historical canvas featuring Jane and her husband, under arrest for treason and brought surreptitiously to the Tower, Jane Grey and Lord Gilbert Dudley brought back to the Tower through Traitors' Gate (April 1840). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Commentary

Edward I extended the south side of the Tower of London onto land that had previously been submerged by the River Thames. In this wall, he built St.Thomas's Tower between 1275 and 1279; later known as Traitors' Gate, it replaced the Bloody Tower as the castle's water-gate. When the Thames was a highway through the heart of England during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, monarchs and state prisoners alike made their formal entrance to the Tower of London through the Traitors' Gate, prisoners arriving under guard from their trials at Westminster Hall. In the era in which Ainsworth sets the novel, Cromwell, Earl of Essex, Queen Katherine Howard (1542), Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1552) and Lady Jane Grey (1553) all passed under massive arch on their way to incarceration and the scaffold. Within the tower Edward I caused to be built a small oratory dedicated to St. Thomas a Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury.

In the leadup to the coronation of Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII's second wife, as Queen, the King ordered St. Thomas's Tower rebuilt to provide upscale lodgings for members of the court. At the time at which the action of The Tower of London occurs, despite its location above Traitors' Gate, the tower would have offered luxurious accommodation. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, the tower had deteriorated. It served as the barracks for a number of the Warders, as well as an infirmary. Twenty years after the publication of the novel, architect Anthony Salvin received the commission to restore St. Thomas's Tower, which externally today looks much as he left it.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Gobetz, Wally. UK - London - Tower of London: St. Thomas's Tower. flickr. 11 September 2017.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 29 September 2017