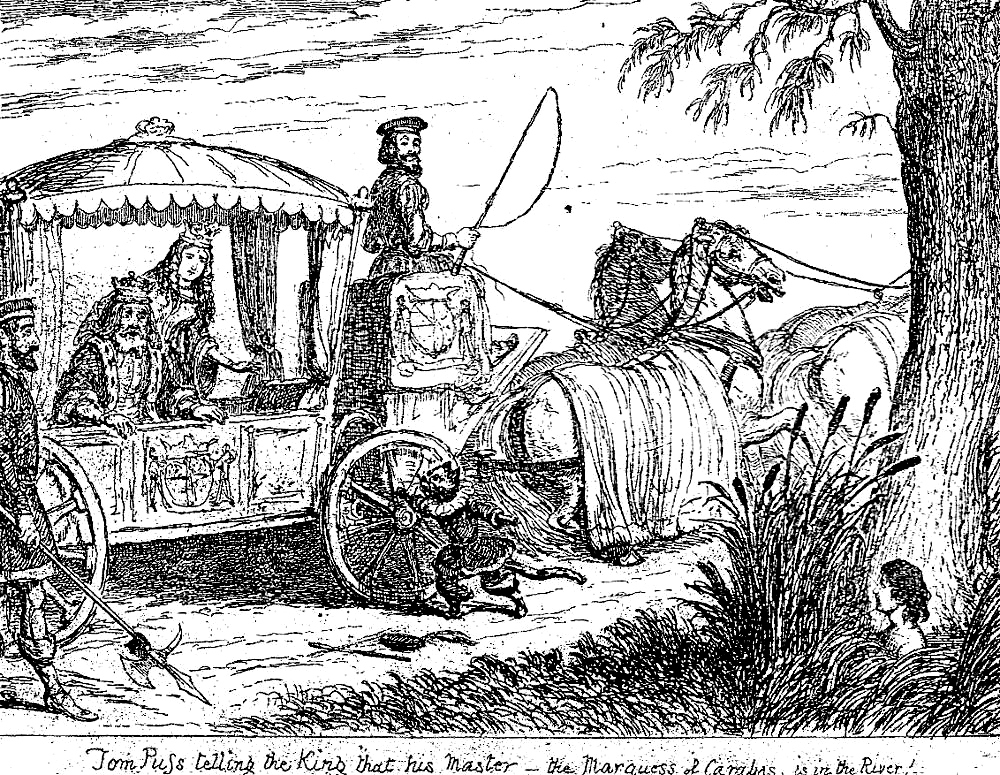

Tom Puss telling the King that his Master .. the Marquiss of Carabas, is in the River (7.1 cm high by 9.7 cm wide, exclusive of caption, framed, facing page 12) — the fourth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1864 and for the fourth and final tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. Dressed in his elaborate suit of clothes seen in the last illustration (when he presented the King with a brace of rabbits, compliments of his master, the Marquis Carabas), Tom Puss now halts the Royal carriage with an urgent request. Apparently, contends Puss, somebody has stolen his master's clothes while he was bathing in the adjacent river, and the Marquis desperately requires suitable clothing. Quite by coincidence, the King just happens to have on hand a suit he commissioned as a gift to thank the Marquis for yesterday's brace of rabbits. In fact, Puss himself had hidden the peasant's clothing so that he could present his master to the King and Princess in a more favourable light.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

It was a fine summer's morning, or forenoon, and Tom told his master to strip and have a bathe, which order he obeyed, and, accordingly, put his clothes on the bank and jumped into the water. Now Caraba's father, the old Miller, was one of those persons who thought that all girls and boys should be taught to swim, and so Caraba was a good swimmer, as were also his two brothers. Whilst Caraba was enjoying his bath Tom pulled off his boots and climbed up a tree that grew by the side of the stream; and after remaining there a short time came down quickly, got hold of his master's clothes, and rolled them up with a large heavy stone, tied up the bundle with a piece of cord, and threw them into a deep part of the river, and cried out to his master that the King's coach was coming that way. His master swam to the side and looking about said, "Where are my clothes?" "Oh, Master, never mind your old clothes, they are in the bottom of the river, but I'll take care that you shall have a new suit. Caraba did not much like the idea of being up to his neck in the water when the Princess was coming there, but being obliged to submit, remained quiet. In a few minutes the "running footmen" came running on before the King's carriage. (In those days foot-men with long staffs or spears in their hands always ran before the horses of the carriages.) Puss stopped these men and told them that whilst his master, the Marquis of Carabas, was bathing in the river some one had taken away his clothes, and that he wished to tell the king of it. The foot-men told this to the guards, the King was informed of it, and the carriage stopped. Puss then came forward and told his majesty that a most extraordinary thing had happened, which was, that whilst his master was bathing, some sly thief had taken away his clothes, and that he was now close by in the river, and could not, of course, present himself to his majesty until he had got another suit of clothes. "Well," said the King, "it is an extraordinary circumstance, and what is very curious and most fortunate, I have brought several new suits of clothes with me intending to present a suit to the Marquis in return for his very nice presents of the rabbits," The king then ordered his servants to get the box of clothes out of the "boot" of the carriage, and then ordered the coachman so drive about for a short time so as to give the Marquis an opportunity of dressing himself, which he was not long in doing, after the carriage left. (Tom had taken care to provide towels for his master.) — George Cruikshank, "Puss in Boots," pp. 11-12.

The Context in Perrault

One day, when he knew for certain that the king would be taking a drive along the riverside with his daughter, the most beautiful princess in the world, he said to his master, "If you will follow my advice your fortune is made. All you must do is to go and bathe yourself in the river at the place I show you, then leave the rest to me."

The Marquis of Carabas did what the cat advised him to, without knowing why. While he was bathing the king passed by, and the cat began to cry out, "Help! Help! My Lord Marquis of Carabas is going to be drowned."

At this noise the king put his head out of the coach window, and, finding it was the cat who had so often brought him such good game, he commanded his guards to run immediately to the assistance of his lordship the Marquis of Carabas. While they were drawing the poor Marquis out of the river, the cat came up to the coach and told the king that, while his master was bathing, some rogues had come by and stolen his clothes, even though he had cried out, "Thieves! Thieves!" several times, as loud as he could. In truth, the cunning cat had hidden the clothes under a large stone.

The king immediately commanded the officers of his wardrobe to run and fetch one of his best suits for the Lord Marquis of Carabas. — Charles Perrault, "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots."

Commentary

For Dick Whittington the cat merely does what comes naturally to bring its owner wealth. Puss in Boots, on the other hand, wins for his master, the youngest and poorest of three brothers, the crops and wealth worked for by others through his own deceit and is far more humanized. (Daniels 2002)

The King's carriage here very much resembles the British monarch's Gold State Coach, an enclosed, eight horse-drawn carriage commissioned in 1760, and built in the London workshops of Samuel Butler. Since this ornate vehicle, now on display at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace, has been used for the coronation of every British monarch since King George IV, Cruikshank would undoubtedly have seen it — as would most Londoners lining the streets to Westminster Abbey — at the coronation of young Queen Victoria on 28 June 1838, a pageant watched by denizens of the metropolis and some 400,000 people from the country who had travelled into London by the new railways. The coach's age, enormous weight, and general lack of manoeuvrability have limited its use to grand state occasions such as coronations, royal weddings, and royal jubilees; it is hardly the sort of vehicle that the royal family would have routinely used for trips through the countryside, but Cruikshank has admirably adapted it as the king's carriage in Puss in Boots. Since the State Coach weighs four tons and is 24 feet (7.3 m) long and 12 feet (3.7 m) high, Cruikshank has shrunk it considerably for the purposes of illustration.

The point of attack that Cruikshank uses enables him to move the story along more quickly than Perrault did, even though he offers considerably more detail about Puss and his plan to render Caraba an eligible aristocratic bachelor by introducing him to the Princess dressed in the latest court fashion rather than peasant's rags. The scenes with Caraba in the river, and then approaching the royal carriage in his new clothes emphasize the carriage and the royal travellers, but include sufficient details to render the images (and the speeded up timeline of the story) credible. In Perrault, Puss took months to execute his marriage scheme, but in Cruikshank's version this scene occurs the day after Puss's presenting the brace of rabbits to the King. Placing the cat-servant against the wheel of the ornate royal vehicle, Cruikshank reminds us of Puss's size. At this point, we see only one of the armed footmen in the entourage (left), holding a pike and looking somewhat surprised at the talking cat in a courtier's costume. As the driver glances down from his post (a royal crest in evidence beneath him) to hear what Puss has to say, he pulls up on the reins to halt the four horses in their caparisons. On the roadway in front of the door to the carriage (inserted doubtless for visual continuity) are Puss's bag and stick. As with the other exterior scenes in this series, Cruikshank has effectively realised the background vegetation: grass, bullrushes, and coniferous tree. In the very corner, completing the scene, the reader's eye is drawn to the naked Caraba himself, his state suggested by his bare shoulders. What Puss is up to here is immediately obvious when one reads the accompanying text opposite.

The second scene involving the King and the Princess in their ornate carriage

Above: George Cruikshank's subsequent realisation of the Marquis of Carabas, fashionably dressed in the latest court style, approaching the royal carriage, Tom Puss, after his Master is dressed, introduces him to the King as the Marquess of Carabas (also facing page 12). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Carpenter, Humphrey, and Mari Pritchard. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1984.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Puss in Boots. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The fourth volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1864. (Price one shilling) 11 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Daniels, Morna. "The Tale of Charles Perrault and Puss in Boots." Electronic British Library Journal. 2002. pp. 1-14. http://docplayer.net/21672800-The-tale-of-charles-perrault-and-puss-in-boots.html

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots." Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts, University of Pittsburgh, 2002. From Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., ca. 1889), pp. 141-147. Edited by D. L. Ashliman. http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault04.html

Schlicke, Paul. "

Stone, Harry. Dickens and the Invisible World: Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Novel-Making. Bloomington, IN: Indiana U. P., 1979.

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 6 July 2017