[The following essay originally appeared in The Orchard. The Journal of the C F A Voysey Society – Number One (Autumn 2012). Readers may wish to visit their website. — George P. Landow.]

‘Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man’, said Francis Xavier, the Jesuit. That was in the sixteenth century. A Victorian architect might have said ‘Give me an articled pupil and I will give you the architect’. So it was with Seddon and Voysey. He could have had no better mentor. Seddon was a leading exponent of modernised Gothic – Gothic for the scientific, industrialised, age. It was not a mere style that Seddon passed on to Voysey, but a way of thinking – a mindset. It had the characteristic Victorian moral tone.

Voysey’s articles with Seddon were signed in 1873. He was sixteen – a fortnight before his seventeenth birthday. Seddon wrote on the articles that he was pleased with Voysey’s work and that he had ‘placed himself in a position to do credit to the profession of an architect’. The Reverend Charles Voysey –Voysey’s father – Voysey himself, Seddon and a witness — an articled clerk, signed the articles.

There is a parallel between the relationships of Seddon and Voysey and between Philip Webb (1831-1915) and his teacher George Edmund Street (1824-1881). Street, like Seddon, was an exponent of modern Gothic – Gothic for the nineteenth century and its new institutions. Street was architect of the Law Courts in the Strand and Seddon was architect of the University of Wales in Aberystwyth. Both Webb and Voysey understood that Gothic principles would transform architecture.

Webb Red House [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Take Webb‘s first building, the Red House (1859), for young William Morris and his twenty year-old wife Jane Burden. The house was as radical as Morris’ choice of a wife from a different social class. In the Red House, Webb applied the principles he had learned from Street, but he jettisoned all the trappings of ecclesiastical Gothic and endeavoured to recreate the frankness of mediaeval vernacular building. The modest red-brick Red House seemed relaxed and welcoming — at a time when formality and a domestic hierarchy prevailed. The Red House was the forerunner of the houses that Voysey would build. Webb and his generation saw the transformation of Gothic from a style — the exponents of which were all-to-often preoccupied with doctrinaire interpretations of mediaeval buildings — to a way of thinking in which the frank use of materials and the visibility of craftsmanship were paramount.

The examples of Voysey's domestic architecture — left to right: (a)14 South Parade, Bedford Park. (b) E. J. Horniman's “Garden Corner”. and (c) Lowicks [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

A nineteenth century innocence and optimism permeate Voysey’s œuvre. The residue of the nineteenth century could still be felt, even when modernism swept all before it. In Individuality (1915), as the Great War was gathering its dreadful momentum, Voysey set out his position – ‘…let us assume there is a beneficent and controlling power… perfectly good and perfectly loving and that our existence here is for the purpose of growing individual characters…’ Voysey echoed the teaching of his father — the unfrocked country vicar, branded a heretic by the Church, who rejected the dogma of eternal punishment and founded the Theistic Church. Here the belief in an era of ‘sweetness and light’, the coming of which was imminent, held sway. Voysey’s occasional unworldliness seems to exert a particular fascination for our often jaded postmodern era.

Voysey did not flourish academically during the eighteen months or so he was a pupil at Dulwich College. Dulwich, despite a long history had, by Voysey’s time, only just attained the status of a major public school. Dulwich provided an education for entry into the professions for the aspiring London bourgeoisie. Voysey is said to have had problems with spelling. He might now have been described as ‘dyslexic’ – but dyslexics often have a high visual intelligence. In the early 1870s he might simply have been branded as a dullard – albeit with a talent for drawing. After he had been withdrawn from Dulwich, Voysey’s father arranged for him to be taught at home by a tutor. There was no likelihood, even if he or his family had been so inclined, of a career for him in one of the favoured professions of the middle-classes — the law, the church, the Civil Service, or the technical branches of the military.

Architecture had an indeterminate social status. The lower levels of the profession were considered a branch of trade. Only the successful and fashionable architect could claim a place among the professions. By the end of the nineteenth century, a mere ten percent of architects had actually joined the Royal Institute of British Architects. In 1879 the Times spoke of the RIBA as ‘a highly respectable trades union’. The debate as to whether architecture was a profession or an art rumbled on until the end of the century. Notably, Richard Norman Shaw, the most prominent architect of his generation, was firmly on the side of architecture as an art.

When Voysey joined his office, John Pollard Seddon (1827-1906), then forty-six, was at the height of his powers. To become an articled pupil was the conventional way of becoming an architect. ‘To be articled’ was simply a more exalted term for ‘to be apprenticed’. Large fees could be charged. The system could be — and sometimes was — abused. But Seddon was an admirable teacher.

Voysey began his architectural training when there was no British counterpart to the French state-controlled École des Beaux-Arts – the only evolved system of architectural education. Its programmes emphasised historicism and theory. Beaux Art students designed façades with columns, pilasters, entablatures and pediments. This was the language of the Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite orders – each with its own iconographical significance. Now it seems remote and alien. Voysey has sometimes been taken for a modernist because he had been taught to dispense with this language in Seddon’s office — as he was taught to dispense with the superficial trappings of Gothic.

The architect to whom a pupil was articled was important. Famous architects insisted upon accepting only pupils with promise. To be accepted as an articled pupil — by an architect of Seddon’s standing — was the first stage to success in an increasingly influential profession. During the consolidating stages of the industrial revolution there were the money and the desire to commemorate the age with monuments – national, civic and ecclesiastical. And there were the houses to build for those whom industry had made rich. There were thus innumerable opportunities for ambitious architects. In the 1860s and 1870s architects were beginning to enter the world of high culture. This was the time of the high water mark of the cult of the aesthetic. Artists and intellectuals sought to synthesise the ethical polarities of sternly moral Ruskinism and the hedonism – the ‘art for art’s sake’ associated with Whistler and the arch-aesthete Walter Pater. These two – and Oscar Wilde — thought that art need serve no moral purpose. Its function was to intensify the experience of living.

Architecture is both a profession and a vocation. Seddon would have been fastidious about whom he allowed to work for him. Architecture calls for a person of letters, a skilful draughtsman, a mathematician, someone familiar with history — a student of philosophy even. So said Vitruvius in Book I of De Architectura. Seddon would have favoured a youth like Voysey who seemed to have Vitruvian potential.

Who recommended Voysey to Seddon? Although Voysey was only at Dulwich for a short time he would have encountered a brilliant art teacher — John Sparkes (1833-1911). He was scholarly – he wrote — was eclectic in his taste in art, a Ruskinian and immersed in the burgeoning philosophy of the arts and crafts. Might Sparkes have been the intermediary between Seddon and Voysey’s father? One can assume that Sparkes would not have suggested that Voysey become a painter. His simplified linear figure drawing was not what was expected of the successful Victorian artist.

At Dulwich, Sparkes taught two contemporaries of Voysey who were to become famous as painters — Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) and Henry La Thangue (1859-1929). Sparkes continued to teach them at Lambeth School of Art where he was Headmaster. Stanhope Forbes and La Thangue were to become leaders of the Newlyn School of painters in Cornwall. This was the centre of British, but French-inspired, plein air – outdoor as opposed to studio — painting. Stanhope Forbes’ best known painting was A fish sale on a Cornish Beach, 1885 – an early attempt at social realism and no mere winsome genre work. The painting did much to publicise the Newlyn artists. La Thangue’s best known work was The Man with the Scythe, 1896, which depicted a girl of six or seven sleeping on a chair in cottage garden, watched anxiously by her mother, while a labourer with a scythe passes. The symbolism was a poignant one for Victorians. Tuberculosis took the lives of many children. Voysey designed a house for La Thangue in Norman Shaw’s garden suburb of Bedford Park. It was never to be built.

Sparkes, in the event, was to become the leading late-nineteenth-century authority on design and art education. He became Director of the South Kensington Schools. These were, for many years, to be the epicentre of British official design education. In 1896, after the South Kensington Schools were designated the Royal College of Art, Sparkes became its first Principal.

John Pollard Seddon (1827-1906) was an intellectual who moved in Pre-Raphaelite circles. He was the younger brother of Thomas Seddon (1821-1856), a close friend of Holman Hunt (1827-1910) — one the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and painter of The Light of the World and The Awakening Conscience – paintings which we may now appreciate for their quaintness, but in their day aroused real emotion. Seddon’s own impeccable Pre-Raphaelite credentials are to be seen with his design for the first major piece of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co furniture – this was for his own draughting and office desk. It is known as ‘King René’s Honeymoon Cabinet’. It had painted panels by Ford Madox Brown, Rossetti, William Morris, Burne-Jones and Val Prinsep. It can be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Seddon was also a prolific designer of stained glass – some of his windows, mostly in Wales, are among the finest Pre-Raphaelite ecclesiastical works.

Seddon had been articled to Professor Thomas Leverton Donaldson (1795-1885). With C. R. Cockerell (1788-1863), Donaldson was one of the last links with the eighteenth century British classical tradition. He was a founding member of the Royal Institute of British Architects and was spoken of as a ‘father of the Institute and the Profession’. Although distinguished as a writer and a teacher, Donaldson built comparatively little. He was a classicist to the core – his projected design for the Albert Memorial and an adjacent Hall of Science show a fine command of the orders and classical monumentality.

Like many young architects, Seddon had been stirred by the writings of Ruskin, notably The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text) (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1852-53). In 1852, the age of twenty-five, Seddon published Progress in art and architecture... It was based on series of lectures he had given at the Architectural Association, that had been founded in 1847 by young articled pupils who were dissatisfied with the banal historical and cultural diet they were offered by their architect mentors. Progress in art and architecture is filled with Ruskinian ardour. It is illustrated with ten fine lithographic plates by Seddon’s own hand. These show the influence of Ruskin’s impassioned style of drawing. There are no complete buildings in Seddon’s book. Seddon, like Ruskin, was concerned with intimate and humanising ornamental detail.

The Renaissance, declared Seddon, was ‘the exhumed mummy of Paganism set up in its place… and the corpse of Classic Art, we hope, will be decently re-interred; for then, and not until then…the tide will flow again and Art in every branch be advanced to the vantage point of modern times over those that are bygone, in the absence of superstition and the increase of science…’

Ruskin had dismissed classicism as arid – an architecture governed by inhibiting rules and prohibitions. Gothic, in contrast, allowed for individual expression. Classicism was the architecture of servilty. Here is Ruskin in his conclusion to The Stones of Venice:

In examining the nature of Renaissance [architecture]… its chief element of weakness was that pride of knowledge which not only prevented all rudeness in, but gradually quenched expression all energy which could only be rudely expressed … art is valuable or otherwise only as it expresses the personality, activity, and living perception of the human soul… if it [does] not show the vigour, perception, and invention of a mighty human spirit, it is worthless.

For ‘rudeness’ we might substitute ‘naivety’, or better still — ‘innocence’. Seddon must have passed on such Ruskinian attitudes to Voysey who desired quotodian ordinariness and restraint. Ruskin’s arguments, often ethical rather than aesthetic, are seductive. Gothic could humanise the societies that industrialisation was destroying. Ruskin was not anti-modern, far from it. But he was opposed to the coarse aspirations and the banality of his times.

Seddon was among the most devoutly Ruskinian of the Gothic Revival architects. After the death of Sir Gilbert Scott in 1878 he succeeded him as Director of the Royal Architectural Museum in Westminster – now long since defunct. It was run on strictly Ruskinian lines. Ornament was the theme of the collection – ornament, the imprint of human aspiration and sensibility upon buildings. The examples in the museum took the form of plaster casts from mediaeval buildings.

Benjamin Woodward's Oxford Natural History Museum. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Seddon himself created fine ornament throughout his career and his many Pugin-like designs for encaustic tile schemes for churches are among the best of the 1860s and 1870s. Voysey would have learned the syntax of ornament and pattern in Seddon’s office. Who knows? — some of the Maw & Company tile designs emanating from the Seddon office in the 1870s may be by Voysey — although they would have been designed under Seddon’s guidance. Seddon must have been impressed by Voysey’s decorative abilities. He asked him to design the three mosaics on his tower for the science block of Aberystwyth University. Like the 1860 Ruskin-inspired Oxford University Museum of Natural History — by Benjamin Woodward (1816-1861), of the Dublin practice of Deane and Woodward — Seddon’s work at Aberystwyth is also an example of gothic in the service of modern science. Voysey’s three mosaic panels show Archimedes – the great mathematician and scientist of antiquity – being offered a model of what looks very like a Midland Railway 4-2-2 locomotive, by a kneeling young man. Another young man is offering a model of a two-funnelled steamship – with its engines, typically for the 1870s, supplemented by sails. This young man is almost certainly a self-portrait of Voysey. The three figures are in no sense mediaevalising and suggest the influence of John Flaxman (1755-1826) – the leading British neoclassical sculptor. John Sparkes who had taught Voysey at Dulwich was, incidentally, an authority on Flaxman. Voysey’s design for the first bound volume of The Studio, first published in April 1893, shows Use and Beauty embracing. Use holds the governor of a steam-engine, while Beauty holds a tulip.

What ornamental models would Voysey have been shown when he was a pupil in Seddon’s office? He must have surely have seen Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture, and his Stones of Venice. The three-volume work is illustrated in a way that can still elicit wonder. It served as both a pattern-book and polemic. Ruskin was much involved with the interpretation of nature in this book and believed the principles he expounded were ‘universal’. He was a theorist, a social reformer and a scholar who had brought poetry to the architectural discourse.

Pugin’s work would have been another important source of inspiration for ornament in the Seddon office. In Contrasts, 1836 – satire and passionate polemic in equal measure — Pugin, like Ruskin, called for the restoration and revitalisation of Gothic. Pugin thought a Gothic ambiance would encourage Catholic piety. Only in Gothic would we find ‘the faith of Christianity embodied, and its practices illustrated’. Pugin’s arguments seem populist and simplistic when set against the subtlety of Ruskin’s. Voysey’s approach to architecture was actually closer to Pugin’s than Ruskin’s. Pugin was, after all, a successful practising architect who, in his short life, had been immensely productive. Pugin’s Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament (1844) – with its numerous chromolithographic plates would have had its place in every church architect’s office library. His delightful Floriated Ornament (1849) would have demonstrated how native plants could be transformed into decorative motifs. The book contains well over a hundred formal geometrical arrangements of leaves and flowers. The boldness and clarity of these designs would have appealed to those architects who seek order, simplicity and precision.

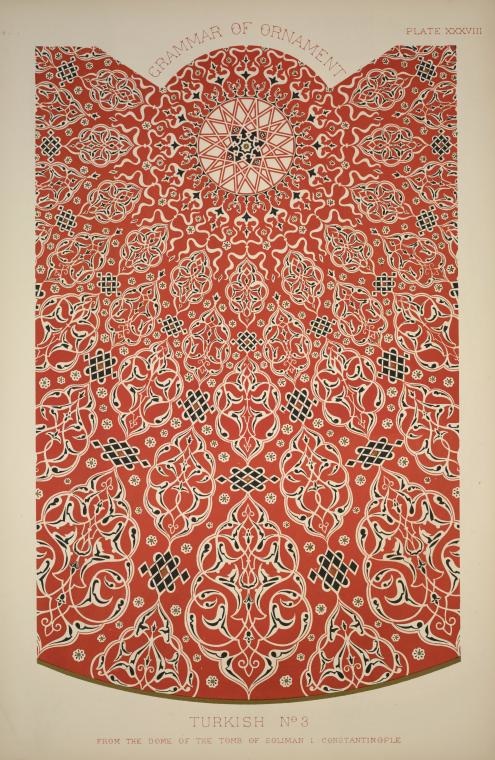

Four pages from The Grammar of Ornament. Left to right: (a) Half-title. (b) Eygptian No. 1. (c) Arabian No. 2 (d) Turkish No. 3 [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

It seems inconceivable that Voysey would not have seen a copy of Owen Jones’ Grammar of Ornament (cover), 1856 in Seddon’s office. Besides its sheer beauty – the writer George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans) described it as being lovely enough for the nurseries of angels – the book was a, still unequalled, compendium of decorative motifs. Whatever Voysey thought of the page after page of magnificent designs from India and the Islamic world in Jones’ book – one suspects Voysey had the Ruskinian and arts and crafts prejudice against Eastern art – he might have found the anonymous drawings in the chapter on leaves and flowers ‘after nature’ a source of inspiration. Could these splendid monochrome lithographs have been by the leading botanical illustrator of the time — Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892)?

After the 1914-18 War, when his arhitectural commissions evaporated, Voysey survived meagrely by producing designs for textiles. His powers as a designer had declined. John Brandon Jones believed that Voysey suffered from a peptic ulcer that affected his ability to work. An ulcer would have been a constant source of irritation and pain. Now, of course, the condition is readily susceptible to treatment.

‘Things are intelligible through a knowledge of their antecedents… the nature of things is latent in their past’, wrote Geoffrey Scott in The Architecture of Humanism (1914). Scott’s book is rare in British architectural writing – it approaches the condition of a philosophical text. The lessons that Voysey learned in Seddon’s office remained with him. There were differences between the attitudes of the two, of course. They were separated by a generation. Seddon, like a good Ruskinian Goth, favoured collectivity in the arts. Voysey stood for individuality. Yet there was always a Gothic subtext in Voysey’s architecture and he was ever a Victorian in his ethical attitudes. If Voysey can be accommodated within the pantheon of modernism it must be with the proviso that it was the modernism of the Seddon era.

Related Material

Last modified 6 December 2012