Part 5 of Benedict Read's Introduction to Gibson to Gilbert: British Sculpture 1840-1914, the catalogue of the 1992 exhibition at the The Fine Art Society, London. The Fine Art Society has most generously given its permission to use information, images, and text from its catalogues in the Victorian Web. This generosity has led to the creation of hundreds and hundreds of the site's most valuable documents on painting, drawing, sculpture, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, metalwork, and the people who created them. The copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with the Fine Art Society. [GPL]

This extension of the functional boundary of the work of art itself to the decorative and the multiple can be seen to govern also (and sometimes at the same time) the parameter of the integrity of the work itself. Gilbert from about 1887, in the Fawcett Memorial and the Winchester Queen Victoria was incorporating into such larger whole works of art a series of smaller ones in the form of participant statuettes. He then began to retrieve some of these from their integral context and use them as individual works in themselves. The Victory originating on the orb of the Winchester Victoria was to be notionnally detached and recreated in different sizes and, often mounted on spheres of onyx or coloured marble, presented to friends of Gilbert's such as John Singer Sargent, Seymour Lucas, Henry Irving, Mark Senior and other.(9) Charity, Truth and Piety incorporated into the Memorial to Lord Arthur Russell at Chenies (1892 -1990) were given a number of independent existences, sometimes as Charity, Hope and Faith, while certain of the supporting figures from the Duke of Clarence Memorial at Windsor (e.g. St George) were also repeated and reformed as separate, detached entities, much to the dismay of royal protocol) in that this happened while the royal commission remained unfinished); Gilbert though entered a quite reasonable defense on the basis of the artist retaining copyright on his work.

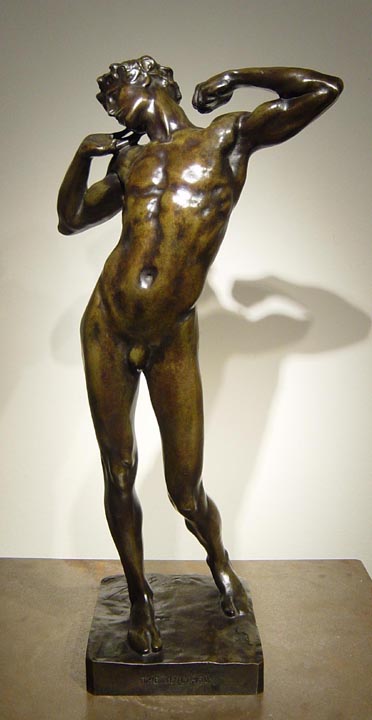

From left to right: (a) Pomeroy's Love the Conqueror (b) Bates's Psyche, (c) Leighton's Orpheus, and (d) Sluggard. [Click on images for larger pictures.]

Other new sculptors also incorporated the work of art within the work of art — Bates in his Pandora (1890), Pomeroy in his Love the Conqueror (1893), Frampton in his Charles Keene (1896) and C.W. Mitchell (1903-05) memorials. Goscombe John's Orpheus has stepped out from his Sir Arthur Sullivan memorial (1902) while, in reverse Leighton's Sluggard, conceived as an independent figure makes a final appearance in its reduced, replicated form in Brock's moving testimonial memorial to Leighton in St. Paul's Cathedral, of 1902, stretching for eternity on the hand of Sculpture. Interestingly enough the closest parallel to Gilbert's use and reuse of the part work as an independent unit was unfolding at precisely the same time as the Winchester Queen Victoria and the Clarence Memorial (these are the examples where this process happens most with Gilbert); it was during the 1880s and 1890s that Rodin was developing his perpetually uncompleted Gates of Hell as the basic store-house for his ideas, with the Thinker, Paolo and Francesca and many other works plying a dual role as parts of the whole that could be detached and set up as independent entities. At the same time it is clear that the reputation and heroization of Alfred Stevens was being propagandized via the circulation of bronze casts or detached, small-scale studies of his major allegorical groups from the Wellington Memorial in St. Paul's Cathedral -- Truth and Falsehood, Valour and Cowardice.

Right: Derwent Wood's Robert Brough. Left: William Brodie's Alfred Tennyson.

The blurring of the fixed parameter of the work of art that was so central to the aesthetics of the New Sculpture can be seen summarized in their treatment of the human head. The portrait in head or bust form is a conventional art form going back at least to antiquity. William Brodie's Alfred Tennyson testifies to the genre's accepted position in the previous generation, Gilbert's Eliza Macloghlin and Derwent Wood's Robert Brough to the convention being continued in the new movement -- though as ever with Gilbert, the notion of this case being conventional defies the known ramifications of artist and sitter's personal and psychological connections. (In the joint memorial to herself and her husband that Mrs Macloghlin commissioned from Gilbert she at one stage required that artist to include somewhere for Gilbert's ashes also to be incorporated.)

The bust could also feature as an independent study of part of another work — witness Brock's Head of Sculpture from the Leighton Memorial and Gibson's Queen Victoria, defined as part so larger commemorative portraits. But certain sculptors took this even further, and turned the study of the part into a study that was itself the whole (again there are interesting parallels with what Rodin was doing, for instance with his Walking Man, evolving as a study of the body in movement without the head, derived from his St. John the Baptist of 1878-80. Not only that (which is general), but Rodin also exhibited his own head studies, the detached head of St. John the Baptist at the Royal Academy of 1882, and a portrait bust of Legros (i.e. specific) and the Mask, Man with Broken Nose at the Grosvenor Gallery that year; the latter unspecific study was bought by Leighton). In England, Gilbert took the lead. His Study of a Head was exhibited as such in 1884: the Illustrated London News critic wrote of its thousand wrinkles and markings of age. "It is difficult to believe this is not cast from life: nothing closer to nature have we seen — nothing so wonderful in its way" (Gilbert, 109). Within three years though, Gilbert had shown in again, only this time he made it specific as the head of a Capri fisherman. More revolutionary though, indeed even epoch-making, had been Gilbert's showing in 1883 of the Study of a Head of a Girl which has to remain an unspecific portrayal of mood and feeling. Goscombe John later claimed it was this piece which brought about "a new outlook in Sculpture" (108). Three years later Onslow Ford showed his A Study; the critic Hepworth Dixon claimed this was "not simply a young girl, it is the, young girl soft-breathing in her fugitive grace, her exquisite unconsciousness; an evanescent and elusive thing, an idea, an ideal made material" (Dixon, 325-26).

In the same article about Onslow Ford, Hepworth Dixon described, more generally another of the new movements key feature, its approach to subject matter. The "new men" were poets as much as sculptors, "who will hold us . . . . by the cunning of some hidden meaning, some suggestive grace, by I know not what of allurement by which we are beckoned into other and ideal worlds". The idea of poetry and imagination, not to say the spiritual, being incorporated in new forms was present already in a Gosse article on Hamo Thornycroft in 1881 -- "he has returned to the direct illustration of the imaginative side of life, he has perhaps more of the pure poetic quality in his art than any of his contemporaries£..the central feature of Mr Thornycroft's work . . . is the pursuit of an imaginative and spiritual aim under forms of absolute truth" (Gosse, 329). Baldry said much the same about Pomeroy in 1898:

He is not satisfied to limit his practice to those pedantic abstractions, to those chilly personifications of subtle fancies, which formerly, and for so long, were accepted as the things with the sculptor should solely concern himself he is an artist capable . . . of the highest flights in ideal sculpture and gifted with qualities of imagination of an unusually sterling type. [78]

Ten years later Dircks wrote that Bayes' "accomplishment . . . Is the expression of a mind influenced by romantic and poetic ideas . . . the very qualities which may be found in Mr Bayes' work: a certain feeling of artistic gaiety and lightness of touch, a free handling of romantic and lyrical ideas . . ." (193).

- The New Sculpture and the Old Sculpture in Victorian Britain

- Advocacy of the New Sculpture in Contemporary Criticism

- Realism and the New Sculpture

- A Revolution in the Decorative Function of Sculpture

- The Work of Art within the Work of Art

- Subject in the New Sculpture

- Influence of French Sculpture

Bibliography

Afred Gilbert. Exhibition catalogue. London: Royal Academy, 1986, pl 29.

Baldry, A. L. Studio 15 (1898).

Dircks, Rudolph. Art Journal (1908).

Dixon, Hepworth. Magazine of Art (1892).

Gosse, Edmund. Magazine of Art (1881).

Created 2 January 2005

Last modified 21 February 2020