emale sexuality in Victorian times was a loaded subject, filled with the contrasting ideals of the domestic wife and the femme fatale. This era was also responsible for introducing the "new woman" and the "fallen woman," two other dichotomous ideologies. The religious and social ideal of femininity was encapsulated in the idea of a woman's mission as daughter, wife and mother, while the cultural (literary and aesthetic) was consumed with images of mystical, deadly and sexually enticing female subjects. Pure women were seen as moral and spiritual guardians, fighting against the immoral influence their evil counterparts posed, not only to their household but also to the entire nation's moral health (Parker 12). These images concerning female respectability were circulated at all levels of Victorian culture, infiltrating the minds of both men and women with not only the positive propaganda and moral reprobation, but also the erotic images, creating a very ambiguous ideal for women.

emale sexuality in Victorian times was a loaded subject, filled with the contrasting ideals of the domestic wife and the femme fatale. This era was also responsible for introducing the "new woman" and the "fallen woman," two other dichotomous ideologies. The religious and social ideal of femininity was encapsulated in the idea of a woman's mission as daughter, wife and mother, while the cultural (literary and aesthetic) was consumed with images of mystical, deadly and sexually enticing female subjects. Pure women were seen as moral and spiritual guardians, fighting against the immoral influence their evil counterparts posed, not only to their household but also to the entire nation's moral health (Parker 12). These images concerning female respectability were circulated at all levels of Victorian culture, infiltrating the minds of both men and women with not only the positive propaganda and moral reprobation, but also the erotic images, creating a very ambiguous ideal for women.

One of the most telling aspects in the treatment of the female figure in this period was the setting in which she was placed. The woman in an urban space presented Victorian society with many complex social and moral problems. The modern urban life of women was the basis for the idea of the fallen woman. Respectable women, it was claimed, could not be part of the public sphere of city life. If women left the safety of the home and were on the streets, it was claimed, they became corrupted by the transgressive values of the city. They would be thought to be prostitutes or vulnerable workingwomen, both victims of a hostile and threatening environment. Due to their outcast status and the underlying erotic nature of their profession, prostitutes became a popular subject, typifying the moral corruption of females in a city setting. Representing economic, social and moral deviancy, a prostitute transgressed all expectations of feminine respectability. The prostitute was a woman who sought out sex, not for procreation but for monetary gain and independence. It was for these reasons prostitution posed such danger to the social ideal of the passive dependent family-oriented female.

The other female type represented in urban space was the endangered workingwoman, often depicted as young vulnerable girls who had become victim to the hostile urban world. Artists such as E.C. Barnes developed telling scenes based on the moral downfalls and the dangers of the city. Barnes' 1860 painting The Seducer utilizes clues and symbols to allude to the underlying meaning of the scene's encounter. The picture depicts a couple standing against a brick wall, a surprisingly popular symbol of erotic or romantic encounter pioneered by John Everett Millais, with the woman on the left and the man to her right. The couple's interaction is not one of a tender or romantic embrace or a struggle between love and duty; rather, there is a gap and an underlying tension conveying uneasiness. The female subject turns away from the intense, almost rude gaze of the man, who boldly attempts to take her hand or her hatbox. This type of interaction would have been deemed highly inappropriate for two strangers of the opposite sex in a public setting, unless they were close acquaintances (Parker 32). To mark his less-than-honorable intentions, the man wears his top hat in the woman's presence, a sign of poor manners and his lack of respect for her femininity. Even the man's body language seems to suggest violation as he steps closer to her without any sign of her permission. Barnes' inclusion of advertisements for the Drama Traviata alludes to the opera which chronicled the saga of a woman gone astray (Parker 33). In addition, a piece of paper with the word "lost" appears above the head of the intimidated female subject. Symbolizing the immortality of the looming misconduct in the eyes of the law and the church, the words "policeman", "rev a Mursell" and "conscience" are visible to the viewer. The hatbox may be a symbol of the young girl's profession and thus her vulnerability in succumbing to a male in the attempt to change economic circumstances. No matter the occupation of the female, Barnes makes clear the impure intentions of the man. The boutonnière in his lapel consists of lilies, an ironic symbol signifying the Immaculate Conception; in other words the man has the virginity of the woman in his pocket. Barnes also adorns the man with a cravat pin in the shape of a skull, a universal symbol of death and evil. As if these symbols did not indict the predator-male enough, his walking stick is decorated with a serpent design, a phallic symbol reminiscent of the original sin of Adam and Eve and sexual temptation. The inundation of moralistic symbolism Barnes instills in the painting directs the viewer to the conclusion of the sexual dangers a city presents to a young woman and an insight into the probable future of a woman who let her guard down. These fallen women portrayed in modern dress and in modern situations were relatable for the contemporary female viewers, and acted as warnings against the moral corruption of city life.

In almost direct opposition to the realism of the modern urban setting is the historical natural settings of the mythological female. These idealized settings and subjects portrayed a completely different attitude towards the female body. Under the veil of historical and mythological representations, artists were able to exhibit these women barely clothed, with strongly sexualized undertones. Almost all artists of the time depicted their fair share of mythological figures, both male and female as purely aesthetic idealized bodies. It may be true that all mythological paintings had a story behind them, but this was rarely of any importance in the pictures. More important was the artist's ability to depict a symbol of divine beauty for aesthetic and possible erotic pleasure. Works by artists such as Herbert Draper represented their highly eroticized subject matter in ancient settings to allow the viewer a sense of pleasure without feelings of guilt for looking at a purely pornographic work, which many of these would have been considered if it were not for their historical ties. His highly erotic works, like Naiad's Pool, the Sea Melodies and Lamia all display beautiful nude women seemingly comfortable with their nudity and sexuality. Naiad's Pool especially elicits feelings of exhibitionism and eroticism. The soft white figure of the freshwater nymph, Naiad, is set off by her dark natural surroundings. Comfortably reclining on a rock, the female body is completely exposed and on display for the viewer. She neither attempts to hide herself nor look away in shame; instead she stares out at the viewers, drawing them into her private domain. The young boy seated in front of her appears to be fishing, but has turned around to also join in the act of gazing at this idyllic natural form.

The voyeuristic qualities of this work, where the viewer feels they have been invited into a private world of a woman's and erotic pleasure, is a common theme. Bathers provided a popular subject for this very idea of venturing into an otherwise closed world of female nudity. Once again, under the guise of ancient historicism, artists illustrated scenes of nude female bathers at Turkish Baths and natural whirlpools. Alma-Tadema's Favorite Custom is a beautiful example of a historically accurate depiction of a Turkish bath, with nude female bathers. The two women within the pool playfully splash at each other, while the others hurry to dress and resume their day. It is not necessarily the women, which cause feelings of eroticism, as it is the voyeuristic quality of the painting. The viewer is allowed to gaze in upon a public, yet highly private and personal act. The essence of the voyeur's position is in his removal from action. He watches and participates in the fantasy, and his satisfaction arises not from doing, but from seeing what is done. These glances into interior spaces were popular among Tadema's works. The highly eroticized Tepidarium is another example of an insight into a private world. The only figure in the painting, a reclining female nude, covers genitalia with a feather, while exposing everything else to the viewer. The feather further tantalizes the viewer, for it appears as if at any moment it will slip from her hands, fully revealing the woman. Her body fills the painting and the low viewpoint makes her appear as if raised on an altar for praise. She intently gazes to her right hand in which she holds an overtly phallic shaped object, a skin scraper. The animal skin rug adds a dark richness and tactile quality to the extremely smooth and luminous atmosphere and sensual figure. The inclusion of these two objects adds a definite eroticism to Tadema's painting. Eroticism arises from not only the woman's flushed nude body, but also the voyeuristic act of gazing in on this private setting.

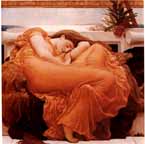

One other recurring theme in voyeuristic eroticism was the figure of the sleeping woman. Offering another glimpse into a private world, this figure is completely unaware of any spectators, and totally vulnerable. The preoccupation with the hypnotic and sensuous female dreamers led artists like Frederic Leighton to paint works like Flaming June. The sleeping figure of the painting is set amongst Greek attributes in a pose "reminiscent of an antique frieze" (Jenkyns 217). This erotic and languid suspension of time is noticeable in the sumptuous figure transcending her semiconscious state and becoming an emblem of indolence and sensuality. Leighton facilitated this effect by his use of rich saffron and 'fervid' coloration dominating the color palette (Jenkyns 217). According to Jenkyns, "The saturating silence and heat of a summer noon are evoked by both the use of color and by the self absorption of the woman's circular, curling pose" (217). The cheeks of this beautifully passive creature were aptly described by an Edwardian critic as "flushed with the impulse of youthful love. Her bosom is pulsating; her arms and feet are bathed in gracious sensibility" (Nead 157). She is an inhabitant of a charmed private environment, far removed from reality; she seems to be dreaming of or awaiting a romantic encounter. Leighton has put not only her sumptuous body on display, but also her purely vulnerable state.

These examples of female sexual identities represented in works of art offer two very distinct views. The urban space depicts a working class female, who must be on guard at all time for her physical and moral well-being depend upon it. In contrast, the mythological and historical depictions of nude beauties seem to encourage exhibitionism and sexual repose. Their vulnerability is embraced and becomes a tool for eroticism. In accordance with the idea that women should remain in private areas, the pampered women portrayed in these erotic images seem to be rewarded for staying in the domestic sphere. Their beauty and morals are intact, despite their nudity, whereas the women of cities, although fully dressed, faced constant bereavement for their supposed lacking moral conviction.

The last representation of female sexuality we will consider, for there are many others, which only confuse the Victorian female ideologies even more, is the figure of the femme fatale. This subject, usually portrayed in accordance with mythological stories, was popularized in the 1870s. This figure of a dangerous yet beautiful seductress first appeared in literary works by Keats, Baudelaire, Gautier and Swinburne. As noted by Elizabeth Lee, "In depictions of the femme fatale, there seems to be a reverent awe and fear of her power. It plays upon the concept of woman's hidden evil: her 'Dark Continent,' her sexuality" (Lee). The question of women's sexual prowess and the fear of her sexual aggression supplied the necessary subject matter to create the idea of the femme fatale. Often presented as a Goddess or enigmatic female, this figure of power was picked up by most of the late Pre-Raphaelites. A favorite of artist's such as Burne-Jones, John William Waterhouse was the mythological figure of Circe. In these works the sorceress uses her supernatural powers to the peril of her male victims (Lee). In Circe offering the Cup to Ulysses, Waterhouse uses a dark palette to hint at the mysterious evils of the scene. Waterhouse places Circe in a position of superiority by situating her above the observer's eye level, tilting her chin up so that the viewer must look up to her as she gazes down upon them. Circe's sensuously sheer gown is no doubt a temptation to Ulysses, who is visible in the mirror behind the Sorceress throne. Her dark hair, eyes and lips are brilliantly contrasted by the pure milky whiteness of her skin. In one hand she holds a goblet filled with a potion tempting Ulysses. In the shadows around her feet there is a pig, alluding to the effect of the magical potion. In her other hand she holds a switch, a symbol of her power over the men she has already turned into lowly swine. The reflected figure of Ulysses in this painting is one of subordination. Although he does not succumb to the enticing Sorceress, he remains in an inferior position at the feet of Circe's mercy by placing the femme fatale, a modern conception, in a historical setting, Waterhouse traces and aligns women's control over men back to ancient times.

The examination of these certain reoccurring icons during this period reveals some of this era's cultural values. The female identity comprised opposing ideals, seemingly popularizing female sexuality while at the same time condemning women who fell into a life of moral desuetude. As seen, the environment of the female played a large role in acceptance of her sexuality. If placed in a modern urban space, a woman was stripped of her ability to make correct decisions and automatically considered immoral, whereas a woman placed in a natural or private/domestic setting was given credence for her eroticism by the aesthetic pleasure she afforded the viewer.

Works Cited

Jenkyns, Richard. Dignity and Decadence: Victorian Art and Classical Inheritance. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992.

Lee, Elizabeth. "The Femme Fatale: Her Dark Continent." http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/fatalsex.html. Visited 5 May 2007.

Parker, Christopher, ed. Gender Roles and Sexuality in Victorian Literature. England: Scolar P, 1995.

Nead, Lynda.Perry, Gill, ed. "Class and sexuality in Victorian Art." Gender and Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999.Erotic Elements in the Art of the Victorian Era

- Introduction

- We Didn't Start the Fire: Discovery of Pompeii's Erotic Art and its impact on Victorian Culture

- Reinstating the Male Nude

- Slave Eroticism

Last modified 18 May 2007