I am happy to be enabled to put before the reader extracts from two letters of Sir J. Herschel, which show, that though my early friend is extending the boundaries of our system, by his observations in the southern hemisphere, his active and indefatigable mind has yet found time to throw its comprehensive glance over some of the highest questions which perplex other sciences. I feel, that the almost perfect coincidence of his views with my own, gives additional support to the explanations I have offered ; whilst the reader will perceive, from the different light in which my friend has viewed the subject, that we were both independently led to the same inferences by different courses of inquiry.

I. The first of the letters to which I allude, and of which I shall extract the greater part, is addressed to Mr. Lyell.

" Feldhausen, Cape of Good Hope, Feb. 20, 1836.

"MY DEAR SlR,

"I am perfectly ashamed not to have long since acknowledged your present of the new edition of your [225/226] Geology, a work which I now read for the third time, and every time with increased interest, as it appears to me one of those productions which work a complete revolution in their subject, by altering entirely the point of view in which it must thenceforward be contemplated. You have succeeded, too, in adding dignity to a subject already grand, by exposing to view the immense extent and complication of the problems it offers for solution, and by unveiling a dim glimpse of a region of speculation connected with it, where it seems impossible to venture without experiencing some degree of that mysterious awe which the sybil appeals to, in the bosom of Æneas, on entering the confines of the shades — or what the Maid of Avenel suggests to Halbert Glendinning,

'He that on such quest would go, must know nor fear nor failing;

To coward soul or faithless heart the search were unavailing.'

"Of course I allude to that mystery of mysteries, the " replacement of extinct species by others. Many will doubtless think your speculations too bold, but it is as well to face the difficulty at once. For my own part, I cannot but think it an inadequate con-" ception of the Creator, to assume it as granted that his combinations are exhausted upon any one of the theatres of their former exercise, though in this, as in all his other works, we are led, by all analogy, to suppose that he operates through a series of intermediate causes, and that in consequence the [226/227] origination of fresh species, could it ever come under our cognizance, would be found to be a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process — although we " perceive no indications of any process actually in progress which is likely to issue in such a " result."

"Now for a bit of theory. Has it ever occurred to you to speculate on the probable effect of the transfer of pressure from one part to another of the earth's surface by the degradation of existing and the formation of new continents — on the fluid or semi-fluid matter beneath the outer crust? Supposing the whole to float on a sea of lava, the effect would merely be an almost infinitely minute flexure of the strata; but, supposing the layer next below the crust to be partly solid and partly fluid, and composed of a mixture of fixed rock, liquid lava, and other masses, in various degrees of viscidity and mobility, great inequalities may subsist in the distribution of pressure, and the consequence maybe, local disruptions of the crust, where weakest, and escape to the surface of lava, &c. If the obstructions to free communication among distant parts of a fluid be great, no instantaneous propagation of pressure [227/228] can subsist, the hydrostatical law of the equality of pressure being only true of fluids in a state of undisturbed equilibrium. If the whole contents of the fissures, pipes, &c., into which we may consider the interior divided, were lava, it is true no increase of pressure on the bed of an ocean, from deposited matter, could force the lava up to a higher level than the surface, or so high. But if the contents be partly liquid, partly gaseous, or partly water, in a state to become steam, at a diminished pressure, then it may happen that the joint specific gravity of lava + gas, or lava+ steam occupying any given channel may be less than that of water; or of the joint column of water + newly deposited matter — which may be brought to press upon it by any sudden giving way of support, and the effect will be the escape of a mixture of lava and gas, either together, as froth and pumice, or by fits, according as they are disposed in the channel. This (taken as a general cause of volcanoes) would account for the great quantity of gaseous matter which always accompanies eruptions, and for the final blow out of wind and dust with which they so often terminate. It has always been my greatest difficulty in Geology to find a primum mobile for the volcano, taken as a general, not a local phenomenon. Davy's speculations about the oxidation of the alkaline metals seems to me a mere chemical dream, and the fermentation of water and pyrites as utterly insignificant on a scale of any [228/229] magnitude. Poulett Scrope's notion of solid rocks flashing out into lava and vapour, on removal of pressure, and your statement of the probable cause of Volcanic Eruptions, in p. 385, vol. ii. 4th Ed. when you speak of the effect of a minute hole bored in a tube, in which liquefied gases are imprisoned, both appear to me wanting in explicitness, and as not going high enough in the inquiry, up to its true beginning, and also as giving, in some respects, a wrong notion of the process itself. The question stares us in the face — How came the gases to be so condensed? Why did they submit to be urged into liquefaction? If they were not originally elastic, but have become so by subterranean heat, whence came the heat? and why did it come? How came the pressure to be removed, or what caused the crack? &c. &c.

"It seems clear that if the gases, or aqueous vapour, were once free, at so high a degree of elasticity as is presumed, there exists no adequate cause for their confinement, — the spring once uncoiled, there is nowhere a power capable of bending it up to the pitch. We are forced therefore to admit, that the elastic force has been superadded to them, during their sojourn below, by an accession of temperature. Now, though I cannot agree with you in your view of the subject of the Central heat, p. 373, vol. ii. 4th Ed. (because I see no reason why the heat may not [229/230] go on increasing to the very centre without necessitating such disturbance of equilibrium as to give rise to any circulation of currents, which you there seem to regard as the necessary consequence of such a state1), yet I agree entirely with what you observe in p. 376, — that the ordinary repose of the surface argues a wonderful inertness in the interior, where, in fact, I conceive that every thing is motionless. Under these circumstances, and debarred from that obvious means of boiling our pot, the invasion of a circulating current, or casual injection of intensely hot liquid matter from below, the question, 'Whence comes the heat?' and 'Why did it come?' remains to be answered on sound theoretical grounds. Now, the answer I conceive to be as follows: —

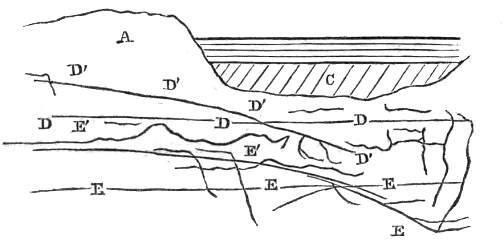

"Granting an equilibrium of temperature and pressure within the globe, the isothermal strata near the centre will be spherical, but where they approach the surface will, by degrees, conform themselves to the configuration of the solid portion; that is, to the bottom of the sea and the surface of continents. Suppose such a state of equilibrium, and that under [230/231] the bottom B of my great ocean D E, the isothermal strata are as represented by the black lines.

"Now, let that basin be filled with solid matter up to A. Immediately the equilibrium of temperature will be disturbed. Why? — because the form of a stratum of temperature depends essentially on the form of the bounding surface of the solid above it, that form being one of the arbitrary functions which enter into its partial differential equation. Immediately, therefore, the temperature will begin to migrate from below upwards, and the isothermal strata will gradually change their forms from the black to the dotted lines. The lowest portions at B will then (after the lapse of ages, and when a fresh state of equilibrium is attained) have acquired the temperature of the stratum C, corresponding to their then actual depth, while a point as deep below B as C is below the surface, will have [231/232] acquired a much higher temperature, and may become actually melted, and that without any bodily transfer of matter in a liquid state from below. But if C be already at the melting point, B will now be so — i. e. the lower level will attain B, and the bottom of the new strata will melt, water included, with which, from the circumstances of the case, they must be saturated. Now, let the process of deposition go on, until, by accumulation of pressure on the bottom or sloping sides, or on some protuberance from the bottom, some support gives way — a piece of the solid crust breaks down, and is plunged into the liquid below, and a crack takes place extending upwards. Into this the liquid will rise by simple hydrostatic pressure. But as it gains height, it is less pressed; and if it attain such a height that the ignited water can become steam, the case before alluded to arises, the joint specific gravity of the column is suddenly diminished, and up comes a jet of mixed steam and lava, till so much has escaped that the deposited matter takes a fresh bearing, when the evacuation ceases, and the crack becomes sealed up.

"In the analysis I have above given of the process of heating from below, we have, if I mistake not, a strictly theoretical account of that great desideratum of the Huttonian theory — 'Let heat,' says he, [232/233] invade a newly deposited stratum from below.' — But why? Not because great currents of melted matter are circulating in the nucleus of the globe — not because great waves of caloric are rushing to and fro, without a law and without a cause in the subterranean regions — but simply because the fact of new strata having been deposited, alters the conditions of the equilibrium of temperature, and they draw the heat to them, or, which comes to the same thing, retain it in them in its transit outwards (the supply from the centre being supposed inexhaustible, and its temperature of course invariable).

"According to the general tenor of your book, we may conclude, that the greatest transfer of material to the bottom of the ocean, is produced at the coast line by the action of the sea; and that the quantity carried down by rivers from the surface of continents, is comparatively trifling. While, therefore, the greatest local accumulation of pressure is in the central area of deep seas, the greatest local relief takes place along the abraded coast lines. Here, then, in this view, should occur the chief volcanic vents. If the view I have taken of the motionless state of the interior of the earth be correct, there appears no reason why any such influx of heat should take place under an existing continent (say Scandinavia) as to heat incumbent rocks (whose bases retain their level) 5 or 600° Fahr, for many miles in thickness. (Princ. of Geol. [233/234] vol. ii. p. 384.4th Ed.) Laplace's2 idea of the elevation of surface due to columnar expansion (which you attribute, in a note, to Babbage,) is in this view inadequate to explain the rise of Scandinavia, or of the Andes, &c. But, in the variation of local pressure due to the transfer of matter by the sea, on the bed of an ocean imperfectly and unequally supported, it seems to me an adequate cause may be found. Let A be Scandinavia, B the adjacent ocean (the North Sea), C a vast deposit, newly laid on the original bed D of the ocean; E E E a semi-fluid, or mixed

mass, on which D D D reposes. What will be the effect of the enormous weight thus added to the bed DDD (rock being heavier than sea)? Of course, [234/235] to depress D under it, and to force it down into the yielding mass E, a portion of which will be driven laterally under the continent A, and upheave it. Lay a weight on a surface of soft clay: you depress it below, and raise it around the weight. If the surface of the clay be dry and hard, it will crack in the change of figure."

"I don't know whether I have made clear to you ray notions about the effects of the removal of matter from above, to below, the sea. 1st. It produces a mechanical subversion of the equilibrium of pressure. 2dly. It also, and by a different process (as above explained at large), produces a subversion of the equilibrium of temperature. The last is the most important. It must be an excessively slow process, and will depend, 1st, on the depth of matter deposited; 2dly, on the quantity of water retained by it under the great squeeze it has got; 3dly, on the tenacity of the incumbent mass — whether the influx of caloric from below, which must take place, acting on that water, shall either heave up the whole mass, as a continent, or shall crack it, and escape as a submarine volcano, or shall be suppressed until the mere weight of the continually accumulating mass breaks its lateral supports at or near the coast lines, and opens there a chain of volcanoes. [235/236]

"Thus the circuit is kept up — the primum mobile is the degrading power of the sea and rains (both originating in the sun's action) above, and the inexhaustible supply of heat from the enormous reservoirs below, always escaping at the surface, unless when repressed by an addition of fresh clothing, at any particular part. In this view of the subject, the tendency is outwards. Every continent deposited has a propensity to rise again; and the destructive principle is continually counterbalanced by a re-organizing principle from beneath. Nay, it may go farther — there may be such a tendency in the globe to swell into froth at its surface, as may maintain its dimensions in spite of its expense of heat; and thus preserve the uniformity of its rotation on its axis, in spite of the doctrines of refrigeration and contraction, (which, by the bye, had occurred to myself, and been rejected, as inadequate to give a general formula of explanation of volcanoes, &c.) Perhaps I shall recur to this subject on some future occasion; but really the stars leave me very little time to lick into form any geological theories, or even to examine them with any degree of scrupulous severity.

II. The following is the copy of a letter from Sir John Herschel to Mr. Murchison, in explanation of the views expressed in his previous letter to Mr. Lyell. [236/237]

"Feldhausen, Cape of Good Hope, Nov. 15,1836.

"In the letter you allude to as having been written by me to Mr. Lyell, there were some speculations about the effect of central heat on newly-deposited matter, which, judging from some expressions in his answer to that letter, I am inclined to think must have been put obscurely, since he appears disposed to regard the view I took of the subject as identical with some theory ascribed to Mr. Babbage (but, I believe, before propounded by Mitscherlich) about the elevation of strata by pyrometric expansion of the subjacent columns of rock, by an invasion of subterraneous heat. Granting the heat, there is no difficulty in deducing expansions, disruptions, tumefactions, &c.; but this was not my drift. Will it be trespassing too much on your patience if I here state, in brief, what I really had in view — which, so far as I can recollect, has not hitherto been duly, or not at all, considered? If you like to call it my 'theory,' you may do so; but it is not so much 'a theory,' as a pursuing into its consequences, according to admitted laws, of the hypothesis of a high central temperature, which many geologists admit, and all are familiar with.

"Granting, then, as a postulate, a gradation of temperature within the globe, from the observed external temperature at the surface, up to a high state [237/238] of incandescence at the centre: I say, that when solid matter comes to be deposited to any considerable thickness on any part of the bed of the ocean, by subsidence, (or even on the surface of a continent, by volcanic ejection, as in great volcanic plateaux and table-lands, or by the action of the wind,.as in sand hills,) the mere fact of such accession of materials, without requiring any other condition, or concomitant cause, will, of itself, in virtue of the known laws of the propagation of heat through a slowly-conducting mass, immediately subvert the equilibrium of temperature, and induce a change in the form of the isothermal surfaces (curves of equal temperature) in the whole region immediately beneath, and surrounding the point of deposition — causing all those surfaces (which, you will observe, are only imaginary mathematical ones, like lines of equal variation in a magnetic chart — not real strata) to bulge outwards, and recede from the centre in that part. The direct consequence of this will be, that any given point of the surface on which the deposit took place will, when a new state of equilibrium is attained, (supposing it to be so) have a temperature corresponding to an isothermal surface of a deeper order: i. e., it will have become hotter than it was previous to the new deposit; and the same is true of every point in the vertical line drawn from that point downwards. Supposing, as before said, a new state of equilibrium to be attained, (the deposition ceasing, by the filling up [238/239] of the sea in that part) then the temperature of the lowest parts of the newly-formed strata will be that of a point situated beneath the surface of an old continent in the same latitude, at a depth equal to the thickness of the deposited matter. The thicker, therefore, the deposit, the hotter will its lower portions tend to grow; and, if thick enough, they may grow red hot, or even melt. In the latter case, their supports being also melted or softened, may wholly or partially yield, under the new circumstances of pressure, to which they were originally not adjusted; and the phenomena of earthquakes, volcanic explosions, &c., may arrive — while, on the other hand, if no cracks occur, and all goes on in quiet, the only consequence will be, the obliteration of organic remains, and lines of stratification, &c. — the formation of new combinations of a chemical nature, &c. &c. — in a word, the production of Lyell's 'metamorphic' rocks."

"The process described above is precisely that by which a man's skin grows warmer in a winter day by putting on an additional great coat; the flow of heat outwards is obstructed, and the surface of congelation carried to a distance from his person, by the accumulation of heat thereby caused beneath by the new covering.

"You see, therefore, that my object is to get at a geological rimum mobile? in the nature of a vera [239/240] causa, and to trace its working in a distinct and intelligible manner. In future, therefore, instead of saying, as heretofore, 'Let heat from below invade newly-deposited strata (Heaven knows how or why), then they will melt, expand,' &c. &c., we shall commence a step higher, and say,' Let strata be deposited.' Then, as a necessary consequence, and according to known, regular, and calculable laws, heat will gradually invade them from below and around; and, according to its due degree of intensity at any assigned time, will expand, ignite, or melt them, as the case may be, &c. &c. &c.; and, I mistake greatly, if this be not a considerable reform in our geological language."

"According to this view of the matter, there is nothing casual in the formation of Metamorphic Rocks. All strata, once buried deep enough, (and due time allowed ! ! !) must assume that state, — none can escape. All records of former worlds must ultimately perish.

"P.S. — If you think it worth while to read the above speculation whenever a discussion may arise, naturally leading to it, at any meeting of the Geological Society, (not as a formal communication, for I have not time to put it into shape, or work it out in detail, but incidentally) you are quite at liberty to do so; and I shall be glad to know your own opinion of it." [240/241]

Since the first edition of this work was published, Mr. Lyell has received another letter from Sir John Herschel, explanatory of his views on this subject; and I am happy to place before the reader the following extracts, not because there is any necessity to prove that my friend arrived independently at the same conclusions with myself, but because they afford additional illustrations of a view which we both think deserving of further inquiry.

This letter was written by Sir John Herschel previously to the receipt of the first edition of this volume, which I had forwarded to him at the Cape of Good Hope.

"Feldhausen, June 12, 1837."

" I reply to your note, however, immediately, because there are points in it, and in a letter of Murchison's I lately received, but especially in yours, which call for immediate notice on my part, lest I should be supposed to have willingly and knowingly, what our French neighbours call, ' emprunté des idées,' — appropriated the ideas of Babhage; to which charge should any one feel disposed to bring it (B. I am sure will not), I plead not guilty. Till the arrival of Murchison's letter, in fact, I was utterly unaware that Babbage had (or any body else) speculated on that peculiar mutual [241/242] reaction of the surface and interior of the globe, which consists in what, I think, we'must now call' the secular variation of the isothermal surfaces' of the latter. The idea I considered as entirely my own; and I was never more taken by surprise, than when to-day, directed for the first time by an express mention in your letter of a paper of Bab-bage's, abstracted in the Geological Notices, I hunted up all those notices in my possession, and found in an uncut Number (No. 36,) — as I am sorry to say many of these, and other not less interesting brochures which have reached me, still are — an abstract of a paper on the Temple of Serapis, at the end of which a theory identical with mine in that leading point, undoubtedly stands printed.

"Convinced as I feel of the great importance of this general view of geological revolutions, in contrast with all the arbitrary, local, and temporary expedients which have hitherto been resorted to to explain particular phenomena, and to the recourse had to' the volcano and the earthquake,' as the great explaining powers; whereas in this view, these are only symptomatic phenomena, natural and necessary concomitants of systems of action much more extensive, which are constantly going forwards. ...But as I do, at all events, lay claim to absolute independence of speculation on the subject, it is quite right that I should make clear to you and to [242/243] him the progress of my own ideas, and also account for what must have appeared singular in my own; mention of his speculations in my letter to Murchison. And to take the last first: — The fact is, that I never was aware that Babbage had made any communication to the Geological Society on the subject, till Murchison's letter first led me to suppose, and yours expressly stated, by referring to the Proceedings for an abstract, that such was the case. The passage in your book and note appended, (Vol. II. p. 383, 4th Edit.) contain no allusion to the cause of rocks becoming heated from below. The employment of the pyrometric expansion of rocks as a motive power, was, I feel confident, suggested by some one (and the name of Mitscherlich or Laplace, has somehow got connected in my memory with it) many years ago, certainly before 1833. Of this B. must have been as ignorant as I was of his views, as he appears to have based his ideas on Colonel Tottens'3 experiments (when made I know not). And I only remembered to have read Babbage's paper on the Temple of Serapis, published in one of the quarterly journals not long after his arrival from the Continent, in which, so far as I recollect, this point is not touched upon; nor is it in your speech from the chair, where alternate pyrometric expansion and contraction, without reference [243/244] to the cause of the invasion or abstraction of heat, are alone alluded to."

"However, discussion of points of this sort is of little moment in itself; as, if a theory be founded in sound views, it matters little to the world whether A. or B. or A. and B. first entertained it, or whether it arose in the whole alphabet when its seeds were ready to germinate. As regards the course of my own ideas, it was simply this. When I first read your book, I was struck with your views of the metamorphic rocks, and I began to speculate how and why the mere fact of deep burial might tend to raise their temperature to the required point. Three modes occurred: — 1st. Development of heat by condensation; but this cause seemed somewhat feeble, and not very clear in its mode of action, since at every moment an equilibrium of pressure and resistance is established. 2dly. Plunging down into an ignited pasty mass; here however, considering the excessive slowness of the process, it occurred to me that there would be plenty of time for the ignited matter below, not merely to divide its caloric with the newly superposed mass, but to take up fresh from below, and thus to establish a regular gradation of temperature from below upwards. And this led to the 3d and more general view of the matter, which is that of the variation of isothermal surfaces, as stated in my letters to Murchison and yourself." [244/245]

"These notions had been fermenting and regurgitating in the cavities of my brain, from the moment I first read your statement of the metamorphic doctrine in your first edition; but what determined the disruption of the incumbent stratum, and their final explosion, was the reperusal of your little 12mo. edition you were so good as to send me."

"All things considered, however, I do not regret having written what I did: and I am still so far disposed to regard it as publici juris, as to wish that such passages in my letters as yourself and Mur-chison may think eligible for the purpose, might on some fitting opportunity be read at a meeting of the Geological Society. (All idea of my drawing up a regular paper is out of the question, I am so involved in other matters at present.) It will draw attention to the subject, and science will gain by the discussion."

"When people think independently at different times, and excited by different original subjects of consideration, bearing on one more general object, if their ideas converge towards one view of the matter, it is a proof that there is something worthy of further inquiry; and if they think to any purpose, it is hardly possible but that many points will occur to each, which do not to the other, and that so a theory may branch out and acquire a body much [245/246] sooner than it would do by the speculations of one alone; — and indeed such is in some degree the case in the present instance. Babbage, for example, has speculated not only on the heaping on of matter in some parts, but on its abstraction in others, as a cause of variation in the isothermal surface; — and justly; it is a case of the algebraic passage from + to — passing through 0. In envisaging (as the French call it) the question algebraically, the cases could not be separated. Again, he has confined himself to the pyrometric changes in the solid strata, while I have left these out of view, and relied on what I think to be a far more energetic and widely acting cause — the variation of pressure, and the infirmity of supports broken by weight or softened by heat, to produce tilts. Both causes, however, doubtless act, and both rriust be considered in further detail: the former alone may account for the phenomena of the Bay of Naples; the latter must, I think, be called into account for those of Scandinavia and Greenland, and of the Andes."

"I would observe that a central heat may or may not exist for our purposes. And it seems to be a demonstrated fact, that temperature does, in all parts of the earth's surface yet examined, increase in going down towards the centre, in what I almost feel disposed to call a frightfully rapid progression; and though that rapidity may cease, and the progression even [246/247] take a contrary direction, long before we reach the ; centre, (as it might do, for instance, had the earth, originally cold, been, as Poisson supposes, kept for a few billions or trillions of years, in a firmament full of burning suns, besetting every outlet of heat, and then launched into our cooler milky way) still, as all we want is no more than a heat sufficient to melt silex, &c. I do not think we need trouble ourselves with any inquiries of the sort, but take it for granted, that a very moderate plunge downwards, in proportion to the earth's radius, will do all we want. Nay, the internal heat may even be locally unequal; i. e. great in Europe and Asia, small under America, — as it would, for example, if, when roasting at Poisson's sun-fire, the great jack of the universe had stood still, and allowed one side of our terraqueous joint to scorch, and the other to remain underdone. — A hint to those who are on the look out for a cause (if any such there be) for the 'poles of maximum cold,' and the general inferior temperature of the American climate, from end to end of that continent. [247/248]

14 December 2008