[This essay comes from the British Library site, which permits the Victorian Web to include it with under a Creative Commons license. Readers may wish to visit the elegant BL site. — George P. Landow.]

‘Kubla Khan’ and opium

The image of the ‘stately pleasure dome’ decreed in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’ (text) was the direct result of his drug taking. Coleridge famously admitted that the entire poem occurred to him during a sleep brought on by the prescription of an ‘anodyne’, widely believed to be opium (52). In this drug-fuelled slumber, he recalled, ‘all the images rose up before him as things’. Though he tried his best to record them in writing when he awoke, he claims that a visit from ‘a person on business from Porlock’ interrupted him and left him with just scattered memories of these fantastic dreams (52). ‘Kubla Khan’ was finally published in its fragmentary state in 1816, nearly two decades after this dream, when it was clear that it would never be finished. In the same volume, Coleridge published ‘The Pains of Sleep’, a poem originally written in 1803 while he was suffering the most agonizing and terrifying nightmares as a result of withdrawal from opium. Pursued in his nightmares by a ‘fiendish crowd/ Of shapes and thoughts that tortured me’, he feels both ‘Life-stifling fear’ and ‘soul-stifling shame’ (62-63). The appearance of these two poems in the same volume of poetry demonstrates the starkly different ways in which drugs were represented in literature of the nineteenth century.

The use of drugs in the nineteenth century

Left: A bottle of laudanum tablets (i.e., in tabloid form). Each tablet contains 5 minims, the equivalent of around 0.3 gram. Right: A bottle of lead and opium pills: ‘One may be swallowed, with a little water, every three or four hours, until relief is obtained’, 1901.. Copyright © Science Museum, London, and Wellcome Images, used under Creative commons license.

Before the 1868 Pharmacy Act, ‘barbers, confectioners, ironmongers, stationers, tobacconists, wine merchants’ all sold opium (Jay, 61). It was easy to come by and many people took it, including numerous authors, such as Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, Lord Byron, Wilkie Collins, George Crabbe, Charles Dickens, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Walter Scott (Milligan, xxxiii). Other drugs were legally available too: it is possible that Queen Victoria, a figure considered the epitome of respectability, was prescribed a tincture of marijuana for menstrual cramps; there are unconfirmed reports that she wrote a testimonial for the hugely popular product Vin Mariani, a mixture of alcohol and cocaine, and she certainly enjoyed the ‘delightful beyond measure’ effects of chloroform when it was administered to her during childbirth (qtd Aikins 32). Opium in particular was commonly and routinely prescribed for an alarming number of ailments to both children and adults, including ‘nervous cough’, hooping cough, inflammation of the intestines, toothache, dropsy and the hiccups.[7] Laudanum, the most popular form in which opium was taken (dissolved in alcohol) was recommended in cases of fever, sleeplessness, a tickly cough, bilious colic, inflammation of the bladder, cholera morbus, diarrhoea, headache, wind, and piles, and many other illnesses (see Buchan 285, 287, n., 294, 359, 377, 437). The concept of addiction was not understood at this time and it was not until the late nineteenth century that people fully appreciated the horror associated with habitual use and withdrawal.

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

ne author who wrote candidly about both the pleasures and pains of opium use was Thomas de Quincey. His Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (complete text) was first published in the London Magazine in 1821 to mixed reviews. He claimed in this publication to have ‘taken happiness, both in solid and liquid shape’, referring to opium in its different forms. De Quincey’s account was sensational because it openly detailed the enjoyable effects of drug taking: his activities looked suspiciously like recreational use rather than opium use for medical reasons. For example, recording the early days of his drug use, he remembered how he would determine upon a day in the coming week to take the drug. On that same day he would go to the opera to listen to a favourite singer. He claims that the delights to be had were specific to him as an intellectual Englishman. No ‘Turk’ or ‘Barbarian’ could experience the opera’s chorus in the way that he did: as though it displayed the whole of his past life like a tapestry, ‘but the detail of its incidents removed, or blended in some hazy abstraction; and its passions exalted, spiritualized, and sublimed’ (Part II, 'The Pleasures of Opium').

De Quincey’s explicit racism fed many of the images found in the horrendous nightmares he encountered while trying to give up his habitual use of opium, which had increased as he got older. He dreamed of jumbled and merged associations of the ‘Orient’: he ‘was stared at, hooted at, grinned at, chattered at, by monkeys, by paroquets, by cockatoos’ (Part II, 'The Pain of Opium'). It seemed as though he was trapped in such nightmares for thousands of years unable to escape. The transition from a nightmare to waking and seeing his children at the side of his bed was such that he wept. Despite the warning implicit in these accounts, De Quincey’s intriguing depiction of drug use was a huge influence on later writers in the nineteenth century and beyond, including Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, Jack Kerourac and William S Burroughs.

Drugs and criminal underworlds

As the nineteenth century progressed drug taking changed. Opium in particular could be associated with the criminal underworld as well as with medical use, though many drugs continued to be legal. Sherlock Holmes injects cocaine regularly and is found by Dr Watson in an opium den in ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’. Speaking to Watson, Holmes refers to his cocaine habit as one of those ‘little weaknesses on which you have favoured me with your medical views’. Conan Doyle’s ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’ features two characters who, while leading outwardly respectable lives in suburbia, are frequent visitors to clandestine East London opium dens.

In the decadent world of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry smokes ‘opium-tainted cigarettes’ – a fitting detail for a character whose intoxicating amorality seduces Dorian. Lord Henry proved to be the most dangerous influence upon the innocent and naïve Dorian Gray and after the murder of Basil Hallward, it is the memory of Henry’s advice that persuades Gray to seek solace in an opium den where he attempts to ‘buy oblivion’. Gray becomes increasingly desperate to reach this oblivion as the ‘hideous hunger for opium began to gnaw at him’, and despite the horror of the opium den — ‘The twisted limbs, the gaping mouths, the staring lustreless eyes’ — he envies those who are experiencing such new, ‘strange heavens’ (ch. 16).

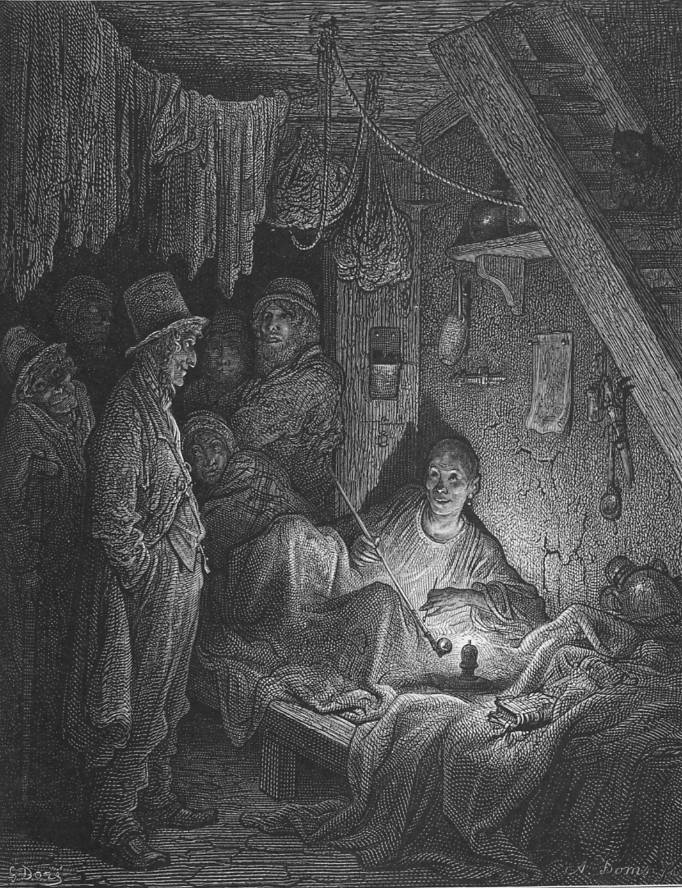

Illustrations of The Mystery of Edwin Drood by two major nineteenth-century artists. Left: In the Court by Sir Luke Fildes. Right: Opium Smoking — the Lascar's Room in “Edwin Drood”. [Click on these images for larger pictures. The image at left was not included in the original article.]

Though unfinished at his death, opium and opium dens also feature importantly in Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood. A now famous image by Gustav Doré, ‘Opium Smoking — The Lascar's Room in “Edwin Drood”’ (1872), allegedly depicts the very room in which Dickens’s novel opens. Drugs continued to be a source of both fascination and terror to writers throughout the nineteenth century.Bibliography

Aikens, Kristina. ‘A Pharmacy of Her Own: Victorian Women and the Figure of the Opiate’. PhD Thesis, Tufts University, 2008.

Buchan, William. Domestic Medicine: Or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines. London: A. Strahan and T. Cadell; Edinburgh: J. Balfour, and W. Creech, 1790.

Coleridge, S. T. Christabel and Other Poems. 3rd edn. London: John Murray, 1816.

Jay, Mike. Emperors of Dreams: Drugs in the Nineteenth Century. rev. edn. Cambridgeshire: Dedalus, 2011.

Last modified 9 December 2022