avid Gurney, an archeologist by training, has unearthed a treasure of an unusual kind. It came from his own family history. His great-granduncle, the Reverend Archer Thompson Gurney (1820-1887), had been a man of many talents, mostly if not all connected with his clerical calling, and his younger brother Augustus had prepared a memoir of him. Incomplete, so never previously published, this brings Archer Gurney to life again in intimate detail, and includes extracts from his many writings, most of them now long forgotten. Having inherited this unfinished work, David Gurney has introduced and reprinted it, complete with the excerpts, and added to it the later details of Archer Gurney's life, and several useful appendices, such as a family tree, a timeline and a list of his publications. While memoirs of important churchmen (often written by the dutiful widows or offspring) are by no means scarce, this one adds valuable insights into a cleric whose career was particularly adventurous, and whose correspondents ranged from Charles Kingsley (a schoolfellow at Helston Grammar School in Cornwall) to Matthew Arnold (who sent him a copy of the second edition of his Poems).

Portrait of the Reverend Gurney by Lock and Whitfield,

reproduced by kind permission of the author.

Earlier Gurneys are thought to have preceded him in this vocation, but Archer Gurney himself was born in Cornwall in 1820 to a father in the legal profession, who heard cases involving the Cornish tin-mines. He too first went in for a legal career, studying at the Middle Temple in London, and being called to the bar in 1842. It was not until 1849, after having dabbled in politics, that he was ordained. His first curacy was close to home, in Exeter, but an unsettled period ensued. There was no clear career path in his profession, but several moves later, he obtained the chaplaincy of the Court Chapel in Paris, remaining in Paris until 1871. This was not as grand as it sounds: as David Gurney explains, it was so-named because it was situated in a court reached from two roads. Nor was it the only place of Anglican worship for British residents at the time. A surprising number of English people, around 5,000, were resident in Paris then (see p. 102), and provision needed to be made for their spiritual welfare.

Probably it was among his fellow-countrymen there that the young chaplain met Elise Hammett (1833-1907), whose family had been living in France, and who had been born in Paris. The two were married in London in 1860, after the memoir ends, so unfortunately very little is know about her, except that she herself wrote, published some of her work, and supported Women's Suffrage. But we do know that these early years of marriage were a struggle for the poorly paid chaplain and his growing family. There were five children, all of them born in Paris, only three of whom would survive both their parents. These three were: their eldest son, Gerald (1862-1939), who would eventually become a Catholic priest; their youngest child, a daughter Sybella (1870-1926), who would annotate the memoir of her father (which has since been deposited in the British Library); and another son, who was "of unsound mind." Of the remaining two children, both sons, one died in Paris in infancy and the other would study at Cambridge but then somehow fail to make his way forward, and would apparently take his own life when his widowed mother was living in Oxford, in 1895.

It was hard to be an Anglican priest in Catholic France, especially as the Reverend Gurney took more upon himself than simply holding services. He was determined to help those even poorer than himself, believing as he said later that "charity should cost us something in money, time , and trouble" (Words of Faith and Cheer, p. 220); and he tried to initiate schemes, like a new Anglican church in Paris, with a school attached, that failed to find support. He was opinionated, too, and made enemies by contributing to church controversies at home — attacking Pusey, for example, when he was advocating the Church of England's acceptance of the Papacy. And all this was at a time of great political turmoil in Paris. At length, like some 900 other British citizens, he fled to England in September 1870, with family in tow, just before the Seige of Paris.

The pulpit at St Barnabas, from which Archer Gurney and many well-known High Church Anglicans (including Pusey) preached.

Then he did something that would seem strange for a clergyman now, but was not so at the time, and that he would later need to repeat — he "advertised publicly in the media for a position" (102). There followed, on this side of the Channel, a whole series of brief appointments, including two in Wales, one at St Barnabas, Pimlico, the very hub of Anglo-Catholicism in London. But, for all his strong convictions, hard work and efforts on behalf of the disadvantaged, and despite having held a senior curacy at St Peter and St Paul, Buckingham, near the beginning of his career in the church, there was no sustained rise within the clerical hierarchy. Believing that indifference was actively sinful, he never hesitated to speak his mind, and it seems that just as being an Anglican priest in Paris could be problem, "being an outspoken Anglo-Catholic," as David Gurney says early on in the book, "was often to suffer the displeasure of some bishops and patrons" at home as well (22).

Two qualities sustained him through his unsettled life. One was sheer strength of character. Noting his "intense individuality," his friend, the Reverend James Bandinel, a fellow clergyman and writer, felt that this "gave energy to all that he did" (qtd. 434). He was also motivated by hope. His brother recalled that Archer was fond of a particular ballad by the German poet and folklorist, Karl Simrock (1802-1876), entitled "The Fools of Hope," and was sad that his sibling's own aspirations were so often thwarted. But the longing that his brother also noted, to "attain to some great sphere of usefulness in the English Church, and to poetic fame" (334), was what drove Archer on, both in his practical endeavours, and in his writings.

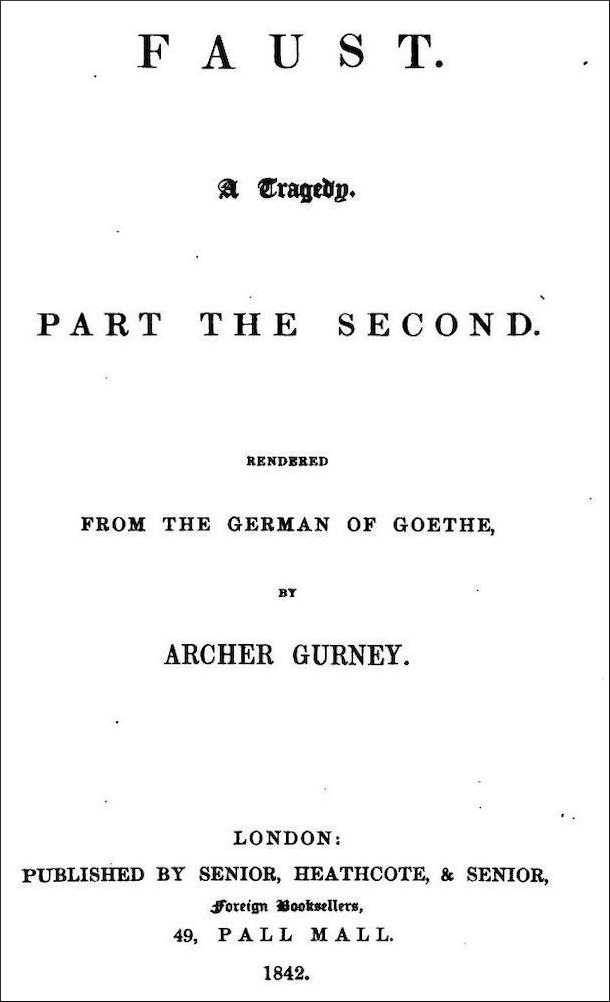

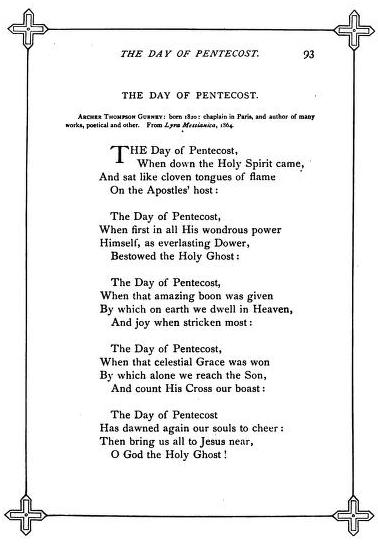

Left to right: (a). Title page of Gurney's Faust. (b) "The Day of Pentecost" in Odenheimer and Bird, 93. (c) Cover of Gurney's Words of Faith and Cheer.

As for the latter, he was certainly part of the literary scene in his lifetime, contributing to many of the periodicals of the time, and publishing some twenty-two works in book form. His English version of Goethe's Faust, Part 2 (1842) and his dramatic poem in five acts about King Charles I (1844-46), are among several of these still available in reprinted editions. Perhaps his most successful book, the wide-ranging Words of Faith and Cheer: A Mission of Instruction and Suggestion (1874, and available as an ebook on Google Books), was compiled from a series of short lectures for the congregation at St Peter's Church, Bayswater, when he was a "missioner" there. While his many collections of poetry may be forgotten now, some of his hymns are still sung, and his Christmas hymn, "Come Ye Lofty" (1852) is reprinted here in Appendix 5: David Gurney tells us that it has appeared in "at least 42 hymnals" (654). Besides those authors mentioned earlier, George Eliot and Dickens were both pleased to hear from him, while Tennyson wrongly suspected that he was the author of a rather poisonous anonymous letter that he received. Some hard words were said, but fortunately the matter was cleared up. Among his other correspondents were William Gladstone (nine letters over twenty years) and the Archibald Tait, who became archbishop of Canterbury (covering an even longer span, 1857-82).

The Reverend Gurney died of kidney disease at the Castle Hotel in Bath on 21 March 1887. His life had not been an easy one, and the record of it provides valuable insights into the struggles that even a well-educated and ambitious churchman could face at that time. While an integrated account might have been more absorbing, and doubtless more succint, it was surely wise to present the historic memoir whole and intact, and to introduce and supplement it in the way David Gurney has done. Between them, he and his great-grandfather have drawn on family history to bring their subject the recognition that so often eluded him during his lifetime.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Gurney, David. A Remarkable Clerical Career: The Life of Archer Gurney, Priest and Poet (1820-1887) . Market Harborough, Leicestershire: Troubador, 2025. Print, 668 pp. ISBN 978-1836289326. Kindle ed. £0.99p.

Gurney, Archer Thompson. Faust: A Tragedy. London: Senior, Heathcote & Senior, 1842. Internet Archive. Web. 23 July 2025.

_____. Words of Faith and Cheer: A Mission of Instruction and Suggestion. Henry S. King & Co.: London Mission, 1874. Google Books. Web. 23 July 2025.

Odenheimer, William Henry, and Frederic Bird, editors. Songs of the Spirit: Hymns of Praise and Prayer to God the Holy Ghost. New York: Anson D.F. Randolph & Co., 1871. Internet Archive. Web. 23 July 2025.

Created 24 July 2025