Formatted with illustrations, captions and links by Jacqueline Banerjee. Many thanks to the National Portrait Gallery, London, for permission to reproduce the portrait of Mandell Creighton, and to Lambeth Palace, for permission to reproduce that of Louise Creighton. You may use the other images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Cover of the book under review, showing Mandell Creighton with his daughters.

At the very end of A Victorian Marriage: Mandell and Louise Creighton, James Covert states that "the underlying purpose of this dual biography has been to explain two people, more interesting perhaps for who they were than for what they did." It might have been fairer to say "even more interesting." Both were outstanding in their spheres. Mandell Creighton (Mandell was his mother's maiden name) was an intellectual giant. He went from being a fellow of Merton College, Oxford, to being the first Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge, and a fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He published five ground-breaking volumes on Renaissance/Reformation Popes. As if this was not enough, his parallel career as a churchman began with ten years from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s as a vicar in Embleton on the Northumberland coast, between his appointments in Oxford and Cambridge. During his years in Cambridge he was also a residentiary Canon of Worcester Cathedral and spent most of the university vacations there with his family. He went on to be Bishop of Peterborough and finally Bishop of London. He died in his late 50s in 1901 a few days before Queen Victoria. Many observers expected him to move from London to become Archbishop of Canterbury, though Randall Davidson (who did receive that appointment in 1903) might have been preferred even if Creighton had lived longer.

Portrait of Mandell Creighton by Sir Hubert von Herkomer, 1902 © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 1335.

Louise Creighton too was formidably gifted. She was born just too soon — in 1850 — to study in Oxford or Cambridge. But without any significant tuition she was one of the first eight women to sit a series of higher examinations offered to women by London University; and she was one of the six who passed with honours. She and Mandell had seven children for whom she acted as teacher/governess in their early years as well as running the household and supporting her husband, particularly in his church appointments. Gradually she became a public figure in her own right, and was involved with many organisations which helped to advance the cause of girls and women. She published twenty-five books including ten written whilst Mandell was alive, and also wrote a memoir, unpublished in her lifetime, which was a key source for this book. Her books ranged from an early novel through several history books for children to a widely admired two-volume "life and letters" of Mandell published three years after his death, and a book on venereal disease published in 1914. Although she was only seven years younger than Mandell, she lived for 35 years after his relatively early death. It is thus a bold claim that these two people were more interesting for who they were than for what they did. Nevertheless, despite the considerable achievements of each of them, Covert is arguably right that they were even more interesting as people.

The Genesis of James Covert's Dual Biography

Covert began work on Mandell in the early 1960s and explains that his teaching and administrative responsibilities delayed the completion of the work for thirty-five years. By 2000 he was a professor emeritus at the University of Portland. At some point during those thirty-five years he discovered that there was enough material about Louise, particularly her letters to her mother and her memoir, to justify making his book a dual biography. He edited the memoir which was published in 1994 and then the letters to her mother which was published in 1998, before completing the biography. He also wrote the new ODNB entry for Louise which mentions the biography but not the entry for Mandell, which mentions Louise's memoir edited by Covert but not the biography.

The Creighton Marriage

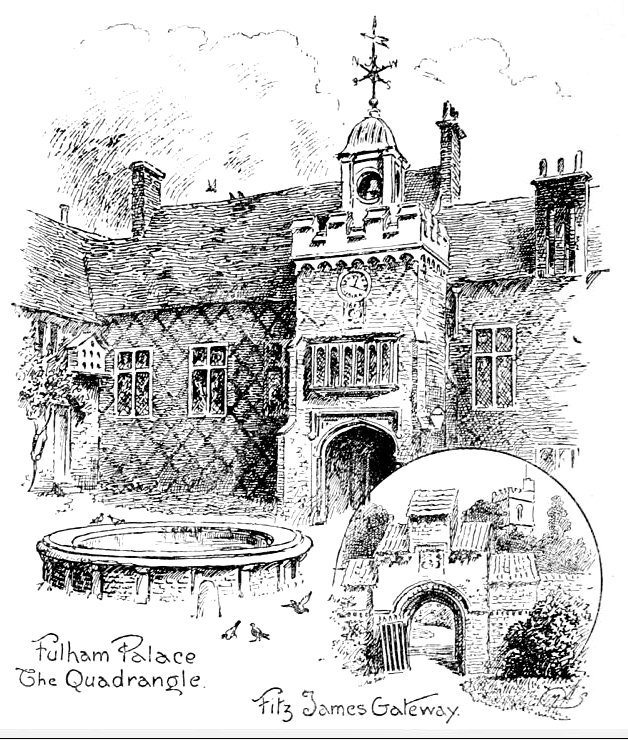

Left: Portrait of Louise Creighton, by Glyn Warren Philpot. © Lambeth Palace. Right: Fulham Palace, where the Creightons lived when Mandell was Bishop of London. [Click on this image for more information.]

Covert begins with an account of how they came to marry. Louise came to Oxford for several weeks in 1871 to stay with friends of her parents. She already knew Humphry Ward, then a Fellow of Brasenose. He arranged a busy social programme for her and seems to have been undecided whether to pursue his relationship with her or with Mary Arnold. The privilege of choosing was quickly denied to him because Mandell saw Louise for the first time at a lecture by Ruskin in the Sheldonian early in her visit and they married eleven months later. The marriage could only have been possible at that early stage if Mandell was allowed retain his Fellowship at Merton, which at that time required the Governing Body to change the rules on married Fellows. The news that he and three other Fellows could retain their position after marriage came on Christmas Eve 1871, and the wedding took place on 8 January 1872 near her home in Sydenham.

Their story highlights the subtleties of social differences in mid-Victorian England. Both fathers were in commerce/trade but Louise's family was much better off. Her father worked in the City, and the family lived comfortably in a large house in suburban London and took regular holidays in Switzerland. In his interview with Mandell about his wish to marry one of his daughters, her father was shocked to hear that Mandell's father had a furniture business in Carlisle and that the family lived over the shop. Although this was perfectly true it also gave a misleading impression: the Creightons did not live as humbly as this suggests. Covert gives us the clear impression that relations between Louise and Mandell's families were never close and relaxed. Neither had uncomplicated personalities. Mandell seems to have been generally liked. He was liberal and tolerant, as well as a Liberal in politics. He wrote to Louise before their marriage to say "Draw as largely as you like on my experience, but come to your own conclusions" (42). On the other hand he puzzled many people by his fondness for extreme statements which he then sought to justify with relish. This may have been the result of a combination of his slightly unusual sense of humour, and his reluctance to be bored. More seriously, he was prone to irritability which sometimes became loss of temper in his own home — though rarely outside it. He was reticent about his personal faith to the point that there was some speculation, when he was a bishop, as to whether or not he had a personal faith. He seems to have given scarcely a thought to the implications of Darwin's work and never to have had any religious crisis. His wife's life and letters cleared up doubts about Creighton for many who were not personally close to him. Randall Davidson, by then at Canterbury, "had to admit that he had not 'discovered or appreciated ... the deepest and best of [Creighton's] qualities' until he read the biography. 'I know of no instance in which the publication of a public man's biography has so greatly raised him in the estimation of good and thoughtful people', he said" (300). Covert follows that quotation with an account of how the book helped people to appreciate Mandell's spirituality.

Louise was sorry about every plan to move from where they were, beginning with the departure from Oxford in 1875, and going on to the translation from Peterborough to London in !897. But Mandell's ready acceptance of each move seems to have been justified, because she settled into each new situation successfully — although this meant that she was as sad to leave it as she had been to go to it in the first place. She depended on her husband, defended him (for example, when he said that all seven of their children were stupid) and seems never to have complained about him. When she died, her obituary in The Times described her as a woman of strong personality and intellectual gifts. Another passage captured her complexity:

Her whole mind was set upon righteousness. Downright in manner and speech, with small regard for the graces and little diplomacies of life, she appeared at times uncompromising and even formidable. But to those who had eyes to see, behind all this lay unflinching sincerity and a deep fund of sympathy, not least for young people. With characteristic honesty she was once heard to say to a friend of widely different character from her own, "As the years go on, I must grow gentler and you must grow sterner." [314]

Left: Embleton Church. Creighton I: facing p. 161. Right: Embleton Vicarage (special permission was obtained for it to be semi-fortified in the Middle Ages). Creighton I: facing p. 151.

The Creightons' decade in Embleton provides a particularly rich section of the book. They were still young (several of their children were born there), they shared the work in the parish, and Mandell was rarely away from home. Louise began to write and he continued to work on his series on the Popes. Social life was full by the standards of most people, with many visits by friends in the better months, with many overnight stays by local friends who in a less remote spot would have gone home after dinner, and some visits to the local aristocracy. There is an entertaining account of their visit to the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland in Alnwick Castle – undoubtedly more entertaining than they found the visit itself. Happily for them it was not repeated when the Duke learned about Mandell's Liberal politics. In retrospect Embleton assumed an even more glowing aura in their memories, set against the much more limited time they had together in their days in Cambridge/Worcester and Peterborough, which involved Mandell's often being away from home, and then in London, which was one of the heaviest jobs in England in either church or state. Louise learned to run a home and struggled with the servant problem in such a remote location. Together they learned how to provide pastoral care and leadership in a widespread rural community.

Almost all their travels were in Europe, particularly to Italy, but they had one trip to the USA in October/November 1886. John Harvard had been at Emmanuel before founding the university named for him. Harvard celebrated its 250th anniversary in 1886 and wanted a representative of Emmanuel to go. Creighton agreed to a request from his colleagues that he should go. Louise went with him. Mandell lectured at Harvard and at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore before spending some time in New York.

Mandell Creighton as Historian

Portrait in Palace Garden, Peterborough [with mortar board]. Creighton I: facing p.83.

There is no question that Creighton was a distinguished historian, but it is hard to judge just how distinguished he was from simply reading this dual biography. He spent only about ten years as a full-time academic. He spent less than seven years at Cambridge and for most of the time combined it with his post at Worcester. He was apparently modest about his own distinction, certainly in the earlier years. He accepted graciously his failure to be appointed to succeed William Stubbs in the Regius Chair in modern history at Oxford a few months before he was offered the Cambridge chair. He had a long-running dispute with Lord Acton about the best approach to writing history. Acton's central point was that Creighton failed to make sufficient moral judgments. It was in a letter commenting on Creighton's work that Acton's most often quoted sentence appeared: "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely" (207). Covert points out that almost no-one who quotes that sentence knows that the next sentence in the letter is "Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority." More people in the twenty-first century may be sceptical about Acton's line of attack than was the case in the nineteenth. Although he and Mandell were far from naturally sympathetic, Lytton Strachey's essay on Six English Historians, published in 1931, covers Creighton alongside Hume, Gibbon, Macaulay, Carlyle and Froude. More significantly Mandell was the founding editor of the English Historical Review which certainly may have happened in part because he was never known to say "no" but must also reflect the regard in which he was held by contemporary professional historians.

Mandell Creighton as Churchman

Mandell Creighton. Creighton II: frontispiece.

Once they left Cambridge/Worcester, the central thrust of the book, Mandell and Louise's life together, is weakened, first because Louise found that the work of a bishop distanced her more than had been the case with Mandell's previous roles, and then because she was a widow for the last 35 years of her life. The most interesting feature of Mandell's work as a bishop was his handling of the controversy in London about growing ritualism in some parishes. He was assailed from both sides of the debate. His approach has been adopted by other Anglican leaders up to the present day but not by all. He was not afraid to spell out the principles that he believed should be followed in general terms but he always tried to avoid driving people into a corner when it came to particular cases. In his address to his diocesan conference in April 1899, Creighton said:

I do not wish to command so much as to persuade. I wish to induce people to see themselves as others see them, to regard what they are doing in reference to its far-off effects on the consciences of others….to remember that the chief danger which besets those who are pursuing a high object is to confuse means with ends; to examine themselves very fully, lest they confuse Christian zeal with the desire to have their own way.... [279]

John Figgis, another historian, said of him, "Creighton's strong hand alone prevented an outburst of the persecuting spirit which would have entirely defeated its own object, and would have left the church shorn of some of its best elements.... Episcopal authority stood very high to his mind, but he was not prepared to support it by coercion, if men (committing as he deemed a sin) refused to bow to that authority. [280]

Louise Creighton's Widowhood

Louise filled her widowhood with service on various public bodies. She was the only woman on the Joint Committee of Insurance Commissioners and was appointed to two Royal Commissions, one on London University and the other on venereal disease, which prompted her later book on the subject. Until she outlived most of them she kept her friendships in good repair, most notably with Sir Edward Grey. As a young man he had been coached by Mandell at Embleton and Louise had approved of him then. Between the death of his first wife, about whom Louise wrote a privately printed memoir in 1907, and his remarriage, Louise saw a great deal of him in London and in the summer in his Northumberland home at Fallodon. Initially she opposed votes for women along with her long-term friend Mrs Humphry (Mary) Ward, but changed her mind and declared her support for the cause in 1906. The friendship survived the difference. For more than twenty-five years after Mandell's death in 1901 she lived in a grace and favour apartment at Hampton Court, but, as age took its toll, she moved to be near a daughter in Oxford and lived at 5 South Parks Road in what had been the home of their early Oxford friends, Arthur and Bertha Johnson. A photograph of Bertha Johnson's portrait of Louise is on the back cover of the book.

More than half a lifetime's work by James Covert alongside other preoccupations has produced a fine double biography which sheds light on the development of Oxford at a critical point in the university's history, on the development of history as an academic discipline, on a Victorian middle class lifestyle based primarily on earnings rather than inherited wealth, on rural life in the 1870s and 1880s, on the handling of conflict within the established church, and, above all, on the marriage of two interesting people.

Sources

Book under review: Covert, James. A Victorian Marriage: Mandell and Louise Creighton. London: Hambledon and London, 2000. 412pp. £35.00. ISBN 978-1852852603.

Illustration source: Creighton, Louisa. Life and Letters of Mandell Creighton. 2 Vols. Vol. I. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1905. Internet Archive. Contributed by St Mary's College, California. Web. 13 October 2015.

Illustration source: Creighton, Louisa. Life and Letters of Mandell Creighton. 2 Vols. Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1905. Internet Archive. Contributed by St Mary's College, California. Web. 13 October 2015.

Created 13 October 2015