Phase One: Youth, the Law, and Narrative Verse

The world-renowned Romantic novelist, poet, editor, translator, biographer, and critic Sir Walter Scott was born in College Wynd, Edinburgh on 15 August, 1771 (a plaque at 8 Chambers Street still marks the spot). His father (also called Walter) was a Writer to the Signet (solicitor); his mother, Anne Rutherford, the daughter of a professor of medicine. Contracting polio at 18 months of age), young Walter was unable to play with other children, so his parents sent him to his grandfather's farm in the border country to the south of the city. For the remainder of his life, he divided his time between Edinburgh and the Borders. In 1775 the family moved to a more spacious house at 25 George Square, where Scott lived until 26. Until the October after his eighth birthday, Scott was educated at home; in 1779, he was enrolled at the High School of Edinburgh, but attended Kelso Grammar School during stays with his grandparents. He forced himself to walk up to thirty miles a day as he lovingly explored the Borders, where he would listen avidly to the traditional songs and legends of the peasantry. Despite interruptions occasioned by illness, Scott studied law at Edinburgh University from 1783, and was compelled by his father to apprentice as an attorney in his father's office on 31 March 1786. On 11 July 1792, he was called to the Scottish bar as an advocate with an annual salary of £250, but poured his energies into a study of Scottish verse inspired by his reading of Archbishop Thomas Percy's collection of folk ballads in Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (originally published in 1765, but revised and expanded in 1767, 1775, and 1794), and by his study of contemporary French, Italian, and German Romantic verse. His first works, published anonymously, were translations of Bürger's Leonore and Der Wilde Jäger(1796), which he followed with a translation in 1799 of Goethe's Goetz von Berlichingen.

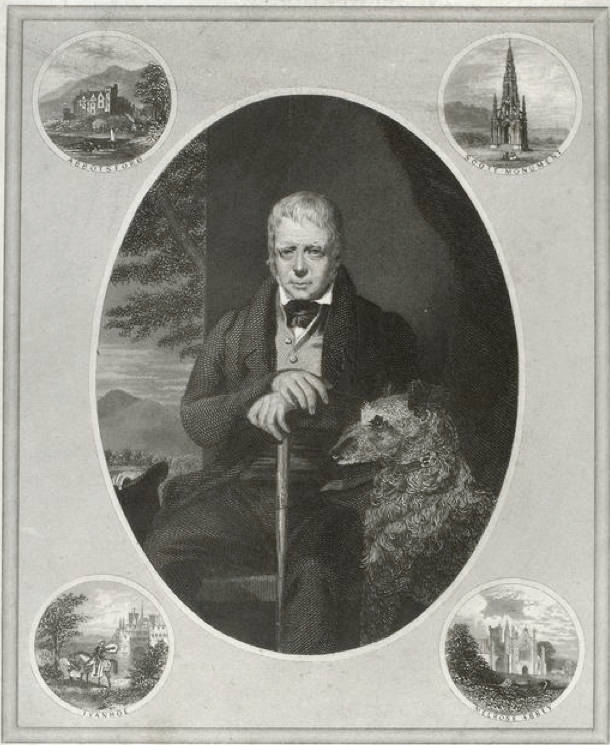

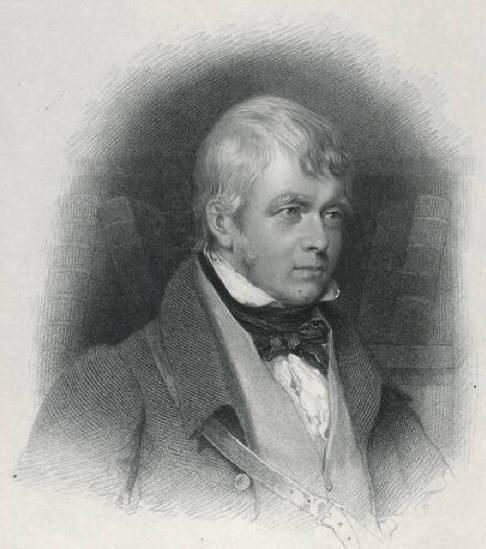

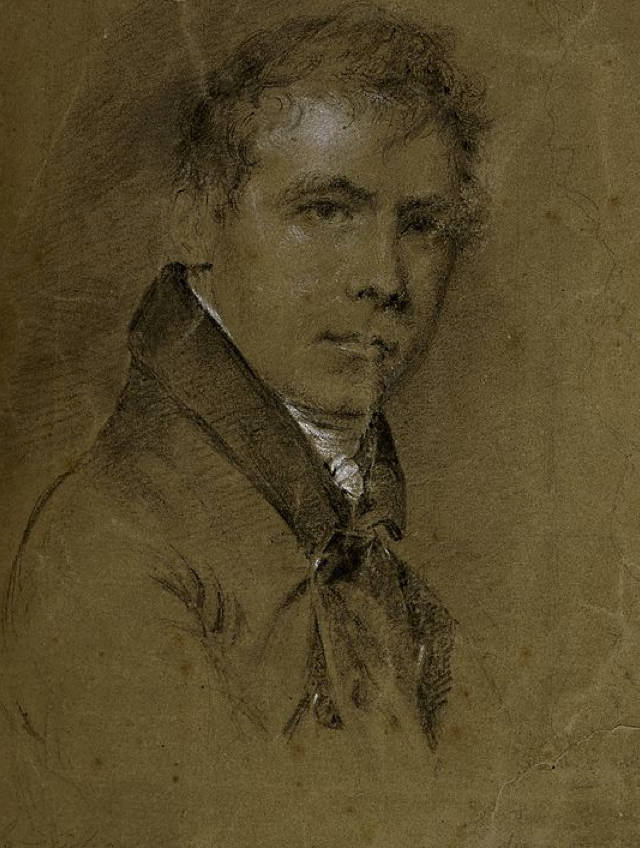

Three portraits of Sir Walter Scott — left to right: (a) Engraved by William Wellstood (1819-1900) from a painting by Sir John Watson Gordon (1788-1864) that is surrounded by vignettes of Abbotsford, the Scott Monument in Edinburgh, Ivanhoe, and Melrose Abbey. (b) Engraved by Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794-1835) from a painting by William Finden (1794-1835). (c) Charcoal drawing by Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823). All three images from the Berg Collection, New York Public Library (image id nos. 482964, 482965, 483679).[Click on these images for larger pictures.] ]

After an unsuccessful love affair with Williamina Belsches of Fettercairn, in 1797 Scott married French émigré Margaret Charlotte Charpentier of Lyon; he was able to support her (and subsequently their five children) through his appointment as sheriff-depute (magistrate) of Selkirkshire. From then on, as a result of his marriage, the on-going French Revolution, and the constant threat of French invasion, Scott became intensely interested in military affairs. Two years later, when his father died, Scott's literary interests were stimulated by his meeting of the Gothic novelist Matthew G. "Monk" Lewis (1775-1818), to whom he showed his translation of a Gothic tale by Goethe. In 1802-3, Scott earned £600 for publishing Minstrelsey of the Scottish Border, containing versions of traditional oral Scottish ballads with rhymes and other corruptions repaired. In 1806 Scott became clerk to the Court of Session in Edinburgh, assuring him an adequate income and leisure time to write. His Edinburgh home during this period was at no. 39 North Castle Street. Scott's long narrative poem about the customs and manner of mediaeval Scotland, The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), was the first in a twelve-year series of metrical romances, the most famous of which is probably The Lady of the Lake (1810), which features a beautiful heroine, a dark Radcliffian villain, and a royal hero in disguise. Read by young Princess Victoria and indeed by people all over England, it ran through 20,000 copies in just six months and established the vogue for Scottish vacations as readers eagerly sought out the places which Scott has used as his settings. The book was Scott's third major venture with James Ballantyne's publishing house, the first two being Scott's edition of Dryden (which included a celebrated biography of the seventeenth-century English poet) and the poem Marmion, A Tale of Flodden Field (a romance set in the court of England's Henry VIII), both in 1808. For a brief few years, Scott's ballads and romances made him the most popular author of the day, until eclipsed by Lord Byron, whose Childe Harrold's Pilgrimage (1812-18) stole the limelight. Scott, acknowledging Byron as his superior in supplying the British market with easily read, exciting narrative verse, completed his last full-length poems, The Bridal of Triermain (1813), The Lord of the Isles (1815), and Harold the Dauntless (1817) as he turned to the writing of historical novels. Deeply patriotic, Scott through his novels may be credited with having rekindled the fading embers of Scottish national sentiment and restoring his countrymen's interest in their nation's past.

Phase Two: The Success of the Waverley Novels and the Agony of Financial Hardship

Statue of Scott by John Steel frm the Scott Memorial omn Princes Street, Edinburgh.

[Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The influence of Scott's prose was felt all over Europe as strongly as that of Byron's verse. Building on the picaresque of Fielding and the atmospheric romances of Radcliffe, Scott produced a new subgenre that enlarged the Novel's horizons, taking his readers back in time and across many countries. Goethe, Dumas, Hugo, Pushkin, and Balzac were all directly inspired by Scott, whose chief (self-proclaimed) disciple was Count Leo Tolstoy, whose War and Peace (1865-72) handles its historical subject matter in the Scott manner, providing a fictional protagonist and setting him against a thoroughly researched historical backdrop.

In his novels Scott arranged the plots and characters so the reader enters into the lives of both great and ordinary people caught up in violent, dramatic changes in history. Scott's work shows the influence of the 18th century enlightenment. He believed every human was basically decent regardless of class, religion, politics, or ancestry. Tolerance is a major theme in his historical works. The Waverley Novels express his belief in the need for social progress that does not reject the traditions of the past.

For the first time in the history of the genre, the novel became a respectable form, read by men as well as women. Recognizing Scott's achievement in verse and prose, in 1820 King George IV made the Scottish writer a baronet — indeed, this was the first title he bestowed upon his ascension to the British throne, Scott having refused the Laureateship from the Prince Regent in 1813 and having proposed it be awarded to Robert Southey instead.

Abbotsford designed by William Atkinson and Edward Blore. [Click on image to enlarge it and to obtain moe information.]

In 1811, Scott purchased the estate of Abbotsford near Melrose on the Tweed River; by the time that he had received the title, Scott had rebuilt the manor house as a mediaeval baronial hall, in which he often entertained on a grand scale in his salad days.

Sir Walter Scott's first novel, Waverley, which he published anonymously in 1814, probably dates back to his first efforts in prose 1805; set against the backdrop of the second Jacobite Rebellion (1745) under the legendary "Bonnie Prince Charlie," the novel concerns the romantic adventures of a young Englishman, Edward Waverley, in the Highlands. In honour of George IV's visit to Edinburgh in August, 182 (the first by a reigning monarch since he time of Charles I), Scott as an amateur antiquarian and authority on his nation's history assisted in the design of the clan tartans that would be part of the pageantry. From the outset, Scott was the prime organizer of the Edinburgh visit, harmonizing the rivalries of the dissparate political stake-holders, the lowland lairds, city councillors, and Highland chieftains

The royal yacht, escorted by warships, arrived at Leith on August 14th in a downpour of rain, and Scott was received on board with enthusiasm. "Sir Walter Scott!" the King cried, "The man in Scotland I most wish to see!" and he pledged him in a bumper of whisky. Scott begged the glass as a memento and deposited it in his pocket. When he returned to Castle Street he found that Crabbe the poet had arrived unexpectedly; in the exuberance of his greeting he flung himself into a chair beside him, there was an ominous crackle, and fragments of the precious keepsake were dug out of the pocket in his skirts. [Buchan 241]

Half the population of the country was drawn to the metropolis for the pageant, stage managed by Scott, looking magnificent in Campbell trews, and starring the King, clad in a kilt of the Royal Stewart tartan. The programme included levees at Holyrood House, a state procession to Edinburgh Castle, a command performance at the theatre, and the conferring of knighthoods on Adam Ferguson and the painter Raeburn.

Strictly speaking, Scott's novels may be divided into three groups: the first series, seven novels in all (1814-1818), called "Tales of my Landlord," deal with Scottish history (e. g., Waverley in 1814 and Guy Mannering, The Astrologer in 1815 to A Legend of Montrose in 1819); those which deal with the Crusades and the Middle Ages (e. g., Ivanhoe in 1819 to The Talisman in 1825); and those miscellaneous novels such as Kenilworth (1821) and Woodstock (1826) which cover later figures and events in European history. Until 1827, he published his novels anonymously; under six aliases he published some twenty-eight novels.

Aside from his important biographical, antiquarian, and historical work, epitomized by his Lives of the Novelists (1821-4) and The Life of Napoleon (1827), Scott was a pioneering critic and commentator. In 1823, he founded the Bannatyne Club for the publication of old Scottish papers, the club being named for George Bannatyne (1545-1608), a collector of Scottish poems. Scott also prompted the founding of a partisan conservative quarterly review (which occurred when William Blackwood established the markedly Tory Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in 1817); he had been an avid contributor to The Edinburgh Review (founded in 1802 by Francis Jeffrey, Henry Broughton, and Sidney Smith, and published by the house of Constable), but had severed his connections with the magazine over its generally Whiggish perspective and somewhat anti-Romantic attitude. For example, The Edinburgh Review was entirely negative about Southey and the other Lake Poets, whose work Scott admired.

Perhaps Scott's greatest financial success was Rob Roy (1817), set in the period immediately following the first Jacobite rising in the Highlands (1715). Although it is often regarded as a portrait of one of Scotland's greatest folk heroes, its protagonist is actually young Francis Osbaldistone, son of a London merchant who, refusing to enter his father's business, goes to visit his rakish uncle, Sir Hildebrand Osbaldistone, in the north of England. When Rashleigh, his host's son, plots against him, Francis, accompanied by Nicol Jarvie of Glasgow, seeks the assistance of the legendary outlaw in the Highlands. Ultimately, Rob Roy slays Rashleigh, and Francis, reinstated to his father's favour, inherits his uncle's estate and marries Sir Hildebrand's lovely niece, Diana Vernon. The picaresque novel sold out its first edition of 10,000 copies in a mere two weeks, making the anonymous "Author of Waverley" a household name in England.

The Heart of Midlothian (1818), although it begins with a vivid description of the Toll Booth Riot (occasioned by the brutality of Capt. John Porteous the Edinburgh city guard in 1736), is the in fact the story of the heroic journey of Jeanie Deans to London to appeal to the Duke of Argyle on behalf of her sister, Effie, wrongfully accused of child-murder. The Bride of Lammermoor (1819) plays out a feud between pro-Hanoverian and pro-Stuart families, The Astons and the Ravenswoods, in the aftermath of 1689's Glorious Revolution; it is often hailed as the perfect Gothic novel since it avoids the ridiculous plot machinations of earlier exponents of the form, Anne Radcliffe and Matthew G. "Monk" Lewis and emphasizes atmosphere and character motivation. In A Legend of Montrose (1819), Scott explores earlier events in the seventeenth century, when the Highland clans rose against the Covenantors in support of King Charles the First during the English Civil War in 1644. Ivanhoe (1819), set in the reign of King Richard I of England, plays out the love affair of two noble Saxon youths, Wilfrid of Ivanhoe and Roweena, against the historical rivalry of the absent crusader-monarch his devious brother, Prince John. In the 1820s, Scott continued to produce historical novels prodigiously: Kenilworth (1821), The Pirate (1821), The Fortunes of Nigel (1822), Peveril of the Peak (1823), St. Ronan's Well (1823),Quentin Durward (1823), The Talisman (1825), Woodstock (1826), The Surgeon's Daughter (1827), and Anne of Geirstein (1829).

Though the novels were all published without his name (even after his "unmasking"), they were grouped into various series which associated them with a common author. Some were published as "By The Author of Waverley"; two appeared under the title "Tales From Benedictine Sources", another two as "Tales of the Crusaders", and four as "Chronicles of the Canongate." The remainder of Scott's novels were published under the heading "Tales of my Landlord," though there is no real connection between the various "Tales," other than the conceit (introduced in the prologue to The Black Dwarf) that they were all written down by one Peter Pattison from stories told to him by the landlord of the Wallace Inn at Gandercleugh, then reworked and sold to the publisher by the village schoolmaster and parish clerk, Jedediah Cleishbotham. (Crumey)

The fictitious editor, the detailed notes on Scots' dialect and history, and the detailed descriptions of locale are Scott's way of giving his stories verisimilitude. By joining the novel to history, Scott created a subgenre that is concerned with humanity's social, political, and moral destiny. He develops his moral with restraint. As the controlling voice, he always remains in his own age, looking back with his reader to earlier times. When he writes about the distant past, as in his Crusader tales, he tends to idealize his characters and their way of life. But even in these romances he reveals his characters from several perspectives to model them in the round. When he writes about Scotland's immediate past, as in Waverley and The Heart of Midlothian, he is most successful in evoking the issues of the era and creating three-dimensional characters with credible motivations. An inherent psychologist and political scientist, he knows that fanatics will make temporary agreements which they will break when it suits them.

Like Shakespeare, Scott altered history for greater dramatic effect, though he used factually-drawn historical characters to colour the background; these, however, he does not focus upon, for they would limit both imaginatively attempts to portray a whole society, but remains objective in his evaluation of his characters and their actions. His many digressions and his great cast of characters both reveal that his interest was not in the story's plot, but rather in creating effective scenes. Scott generally weaves his tale by developing first one and then another group of inter-related characters. Then, after a scene, he clumsily relates it to previous scenes, occasionally resorting to implausible coincidence to knit the various scenes into a coherent plot. Although he did not serialise his work as Dickens was to do, he attempted to satisfy the capricious tastes of a developing reading public. Whereas Jane Austen had shown the impact of events upon the internal conditions of her characters, Scott never really abandoned the external mechanism of a hero-and-heroine centred plot and the inevitable happy ending.

Since 1808 Scott had been a partner in the publishing house of his friend John Ballantyne; in 1826, when his firm was caught up in the bankruptcy of the house of Archibald Constable (occasioned by the death of one partner and the retirement — with his capital — of another), Scott chivalrously but unwisely agreed to shoulder a debt of £120,000. His beloved wife had died on 14 May 1826 and he himself had gallstones, but he was determined to pay off the debt through his own labours. Trusting the soundness of Constable's firm, Scott sold the London publisher the copyrights of many of his novels, but did not receive full payment ("which, comments Buchan, "should have warned him that the great publisher had no greater command of ready money than himself" [238]). Deprived of copyright royalties on sales of his works in the United States by ruthless Yankee piratical publishers, Scott wrote himself to death, mostly through hack editorial work. In 1831, he took a Mediterranean cruise to restore his health, but in July of the following year returned to Abbotsford, where on 21 September he died after suffering a series of strokes. He is buried at Dryburgh Abbey. However, the city that he made a literary locale chose to honour him twelve years after his death with the Scott Monument (constructed of Binnie stone, taken from shale workings near Linlithgow), which is 200.5 feet high and 55 feet square at the base; one ascends to its upper gallery by climbing 287 steps. The Monument and the nearby Waverley Station recall even today his enduring reputation. Through his verse and prose narratives Scott projected an image of his native land that continues to attract tourists from all over the world. In 1847, his family foolishly sold off his remaining copyrights, but were consequently able to pay off all creditors in full.

Web Resources

Crumey, Andrew. "Sir Walter Scott."

"Scott, Sir Walter." Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2000. http://encareta.msn.com 1997-2000 Microsoft Corporation.

"Sir Walter Scott, Writer: 1771-1832" http://www.efr.hw.ac.uk/EDC/edinburghers/walter-scott.html

Sir Walter Scott, Scottish Novelist and Poet, 1771 — 1832 http://www2.lucidcafe.com/lucidcafe/library/95aug/scott.html

"Sir Walter Scott, 17th August 1771 — 21st September 1832." http://www.catharton.com/authors/1.htm

"Sir Walter Scott, 1771-1832" http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/wscott.htmReferences

Booth, Michael R., Richard Southern, Frederick and Lise-Lone Marker, and Robertson Davies. The Revels History of Drama in English, Vol. 6, 1750-1880, ed. Clifford Leech and T. W. Craik. London: Methuen, 1975.

Buchan, John. Sir Walter ScottLondon: Cassell, 1932; rpt., 1987.

Harvey, Sir Paul. The Oxford Companion to English Literature, rev. Dorothy Eagle. Oxford: Clarendon, 1983.

Lang, Andrew, ed. Scott's Waverly Novels, Vol. 48, Chronicles of the Canongate. Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1894.

MacLehose, Robert. "Scott and the Theatre." Sir Walter Scott, 1771-1971: A Bicentenary Exhibition. Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1971.

Millgate, Jane. Walter Scott: The Making of the Novelist. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987.

Mitchell, Jerome. The Walter Scott Operas: An Analysis of Operas Based on the Works of Sir Walter Scott. University of Alabama Press, 1977.

Rowell, George. The Victorian Theatre 1792-1914: A Survey. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1978.

Last modified 8 September 2014