The following detailed description of Glasgow dates from 1868 — that is, from a time when the city had already become an industrial powerhouse and host to some of the U. K.’s worst slums but just before the creation of many of its characteristic buildings and monuments. In at least one case, the University of Glasgow, plans were well under way for the construction of a major complex. In transcribing the following paragraphs from the HathiTrust online version of the Gazetteer’s entry on Glasgow, I have added paragraphing, subtitles, and links to relevant material on this site, including Victorian images and modern photographs and material from other Gazetteers, such as the city map immediately below, which comes from Blackie. Red dots have been added to the map to make finding the Cathedral and main streets, such as Trongate and Broomielaw, easy to locate. — George P. Landow]

Glasgow. Source: Walker Graham Blackie. The Imperial Gazetteer. Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1855. Click on image to enlarge it.

lasgow, a city and a royal and parliamentary borouyh, in the lower division or ward of county Lanark, Scotland, returning two members to parliament. Its name has been variously derived from the Gaelic words signifying “a grey smith,” or from the Celtic for ‘a dark ravine,” near the cathedral, where its earliest inhabitants are said to have settled, the latter derivation being probably the true one. A portion of the city stands upon each bank of the Clyde; the chief part of it, however, being situated upon the North side of the river. It is distant by 405 ¼ railway miles from London, via Crewe, Lancaster, and Carlisle, which is the most direct route, 42 from Edinburgh, and 22 ½ from Greenock; and it ranks, on account of the extent and importance of its commerce and manufactures, not only as the trading capital of Scotland, but as, perhaps, the second, and certainly the third city, of the United Kingdom. Although the approaches to it, whether by road or rail, are by no means picturesque, still the city itself in many parts of it presents a very handsome and substantial appearance, from the fact that it is entirely built of stone.

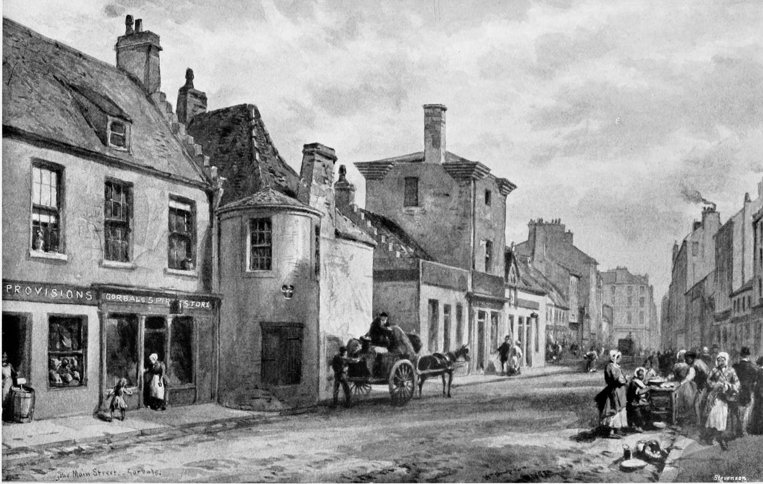

Main Street, Gorbals [Glasgow] by William Simpson. Watercolor. 1849[?]. Source: Renwick's Glasgow Memorials, frontispiece.

Many of the houses, especially in the business parts, consist of flats, and are occupied by several distinct families, but those in the more fashionable localities are generally what are termed self-contained. Its municipal and police jurisdiction extends not only over the burgh of Glasgow properly so called, but also over the districts of Hutcheson Town, Gorbals, Laurieston, Tradeston, and Kingston, as far as Govan, on the South side of the river; Anderston, Blythswood, and Port-Lundas, on the North and Northwest, and Calton and Bridgeton on the East. All those districts are densely populated, and some of them are almost entirely occupied by artizans and hand-loom weavers.

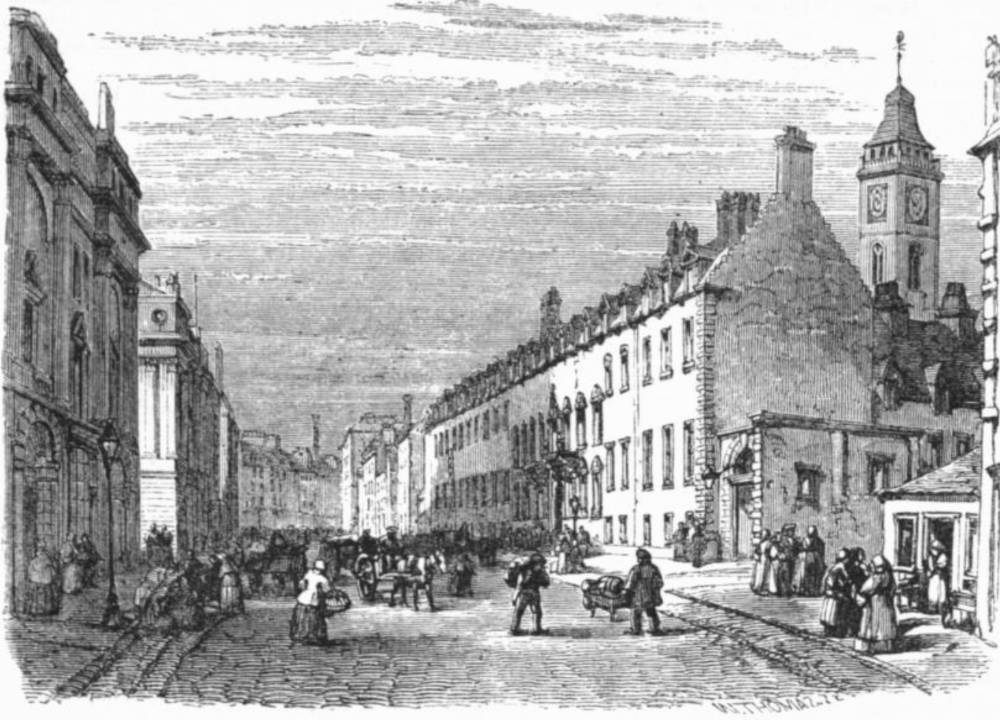

Thus the city, in its entirety, occupies an area of nearly 5 miles from East to West, by about 2 miles from North to South. The earliest portion of it is the line of street which passes southwards from the cathedral to the Clyde by way of the High-street and the Salt Market, and from the junction of these two the Gallowgate runs to the eastward, while the Trongate and Argyle-street lead to the western and more fashionable quarters of the city. From this latter street, opposite to St. Enoch’s-square, a wide thoroughfare of handsome shops, called Buchanan-street, runs northwards, being also connected with Argyle-street by an arcade. At its junction with St. Vincent-street stands the Western Club. Going either by St. Vincent-street or Sauchiehall-street, the passenger arrives at the West end of the town, where he finds Blythewood-square, Newton-place, Woodside crescent and terrace, Claremont-Park gardens and terrace, and the numerous other ranges of sumptuous buildings which form the residences of those opulent merchants and men of business whose sagacity and enterprise have not only rendered Glasgow as prosperous as it is, hut have also adorned the city with the most magnificent public and private edifices, and have spared no expense in making this quarter of it a fitting habitation for a class of citizens of their wealth, liberality, and taste. Returning once more to the business-like portion of the city, we have Miller-street, Virginia-street, Queen-street, Cochran-street, Ingram-street, and others in the vicinity of the Exchange, consisting of massive piles of buildings, which are either shops, or the offices and warehouses of merchants, manufacturers, bunkers, and lawyers. Parallel with Argyle-street are St. Vincent-place (in which stands a bronze equestrian statue of Queen Victoria, by Marochetti), St. Vincent-street, George-seet, Regent-street, and Bath-street, all of which run westward. They were formerly inhabited by those wealthy private families who have migrated further westwaid, and still contain a number of splendid mansions. The buildings, however, have lost their status as dwelling-houses, and are now used as various kinds of business chambers and commercial offices.

Two Glasgow monuments by Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867). Left: Queen Victoria. Unveiled 1854 (re-erected, 1866). Bronze on a red and grey granite pedestal with bronze reliefs. George Square. Right: The Duke of Wellington. Unveiled 1844. Bronze on Peterhead granite pedestal, with bronze narrative reliefs. Royal Exchange Square. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In Queen-street, opposite the East end of Ingram-street, is the Royal Exchange. This noble building was erected in 1829 at a cost of £50,000. It is in the Corinthian style of architecture, is entered by a triple columnar portico, and surmounted by a lantern. It stands in an area, on two sides of which are handsome stone buildings occupied as warehouses, shops, and counting-houses, while in front is a colossal equestrian bronze statue of the Duke of Wellington, by Marochetti, and at the back the Royal Bank, built alter the model of a Greek temple. On each side of the bank an ionic arch leads into Buchanan-street. The newsroom in the Exchange is 130 feet long by 60 broad, is a remarkably elegant apartment, and is well worthy of inspection by the visitor. Proceeding northwards from the front of the Royal Exchange, we come to George-square, in which there are several first-class hotels.

Robert Burns/span> by George Edwin Ewing (1828-1884), assisted by Francis Leslie (1833-94). Reliefs by James Alexander Ewing (1843-1900). 1876-7 for the statue, unveiled 1877.

In the centre of it stands a Doric column surmounted by a colossal statue of Sir Walter Scott. On the South side is a bronze statue of Sir John Moore (who was born in the Trongate in 1701), by Flaxman, and in the Southwest corner a seated bronze statue of James Walt, the celebrated engineer, by Sir F. Chantrey.

The General Post-office fronts this square on the South side, returning again down Queen-street, we pass the National Bank, and emerge into that long line of street which bears the designation of the Gallowgate, at its eastern division, then of the Trongate, and lastly Argyle-street, as it passes westwards, the whole of them together running in a continuous line of buildings for upwards of 3 miles. A few of the ancient houses yet remain, but almost all of them have been replaced by more modern structures, in which almost every variety of trade and occupation is now carried on. A little way from the foot of Queen-street, on the other side of the way, is Dunlop-street, in which is situated the Theatre Royal (another theatre called the Prince's being in West Nile-street); and opposite to it on the left is Miller-street, which was once exclusively occupied by the Virginia merchants, but is now converted into warehouses and offices. Proceeding still eastwards we come to Glassford-street, in which may be noticed the Trades’ Hall, and farther on, at the northern end of the street, the Bank of Scotland.

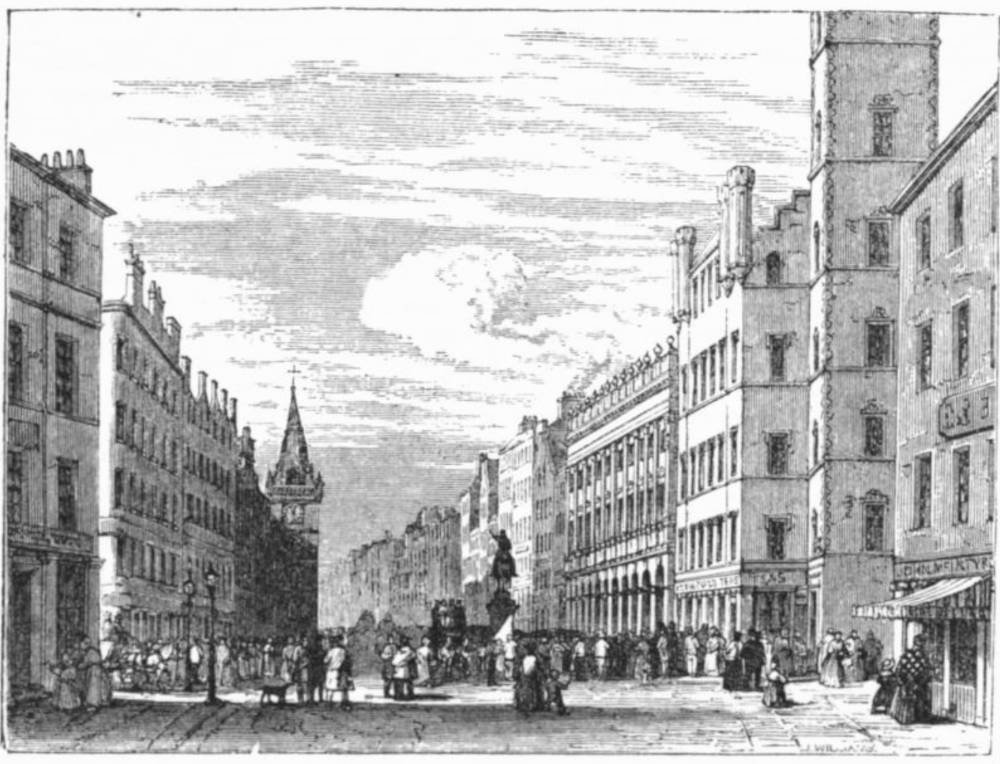

Trongate and the Old Exchange, Glasgow. “Drawn from nature by R. Carrick.” From Blackie.

The county buildings are situated in Wilson-street, which branches off from Glassford-street, opposite to which, and running down to the Clyde, is one of the most ancient streets in the city, where even yet some few of the old houses may be seen standing. This is called Stockwell-street, and some seventy-five years ago it was a very important thoroughfare, as it formed the principal approach to Glasgow over the old bridge which spanned the river at its foot. The next street, eastward, to Glassford-street, and running parallel to it, is Hutchison-street, in which is the Merchants’ Hall, in the inner entrance to which is a marble statue of Mr. Kirkman Finlay, an eminent Glasgow merchant; and at the upper end of the street is Hutcheson’s Hospital, a building founded by two brothers who left property for its support on the South side of the river, in the suburb now called Hutcheson Town. It supplies education and maintenance to a certain number of poor boys, and busts of its benevolent founders are placed in front of it. Still farther to the East is Candierigg-street, in which is the new city hall, an enormous building, capable of containing 1,000 persons, a large and commodious bazaar and general market-house, and extensive wholesale and retail warehouses. The street is terminated by St. David’s church. On the side of the Trongate opposite to the Candleriggs is King-street, where once a market for butcher's meat, fish, and vegetables was carried on, and at the end of it, connecting Stockweli-street with the Salt Market, runs the Bridgegate.

The Trongate in 1849 by William Simpson. Drawing. Source: Renwick's Glasgow Memorials.

In this portion of the town several of the ancient buildings of the city are still remaining, and the various lanes and closes with which it abounds are densely inhabited by the poorest and most squalid of the population, a great proportion of whom are Irish, and who upon any occasion of excitement become very quarrelsome and riotous, and afford much trouble and anxiety to the authorities. Returning to the Trongate up King-street, and proceeding still eastward, we arrive at the Tron church and steeple, and a little further on is the cross, of which the original steeple still remains. From this the High-street runs to the North, the Salt Market to the South, London-street and Monteith-row to the Southeast.,and the Galiowgate to the East. Close by the cross on the North side of the Trongate stands the Tontine Hotel, so called because it was built on that principle. It is under a piazza, and contains a large newsroom, which, before the building of the new exchange, was the principal place of meeting for the merchants and men of business of the city. In front of it stands, on a pedestal, a metal equestrian statue of King William III., which was given to the town by James Macrae, a citizen of Glasgow, who was somo time governor of Madras. Tho gaol and the court-houses once stood at the corner of the Trongate and High-street, but the site is now occupied by shops and warehouses, and the buildings themselves are removed to the bottom of the Salt Market. They are in the Grecian style of architecture, and lie on the right-hand side of the way in going towards the “Green.” The townhall, however, still remains, and contains portraits of some of the English and Scotch kings, and a marble stutue of William Pitt, by Chantrey. The Salt Market, of which, as well as of Glasgow, we have so lively a picture in Sir W. Scott’s “Rob Roy,” is in modern times tenanted by a very different class of inhabitants to that which occupied it in those days.

It is now one of the most squalid parts of the city, the lower portion of it being especially dirty, and crowded by the stores of brokers, old clothes dealers, and a miscellaneous horde of the poorest and most miserable dregs of the population, whose very means of existence are an enigma to the stranger who has to thread his way among them. On the left side of it is St. Andrew’s-square, the area of which is chiefly occupied by St. Andrew’s church. At the extreme lower end of the Salt Market, and opposite the courthouses and the gaol buildings, is an extrusive area in which “Glasgow fair” is held annually for a week at the beginning of July; and on the left lies the “Green,” which covers an area of 110 acres, and has a good carriage drive of 2 ½ miles round it. In oldden times this used to be a favourite resort for the wealthy and aristocratic classes of the citizens, but they have now laid out a fine park on the estates of Woodlands, Kelvingrove, and Claremont, in the western parts of the city, and the Green is now almost entrely left to the humbler classes of the comunity. by them it is greatly valued, both for the space which it affords for air and exercise, and also for its convenience as a washing and bleaching ground, since it is not only bordered by the Clyde, but boasts of several fountains of fine spring water.

Not far from the entrance is a freestone obelisk to the memory of Nelson, 144 feet high, erected by subscription at the cost of £2075. From the Green itself a view is obtainod down the river, showing the bridges and the extensive ranges of buildings which stand on the opposite side; while at a few miles’ distance to the South and Southeast may be discerned the Cathkin Braes and the mansion of Castlemilk, at which Mary Queen of Scots is said to have lodged on the night of the battle of Langsido, which was fought on the 13th May, 1567, after her escape from Lochlevin Castle. On the South and Northeast sides of the Green are seen the tall chimneys or “stalks,” as they are called in local parlance, of several spinning and weaving establishments, and of factories of various kinds, from which dense volumes of smoke proceed, and not unfrequently impart to the Green and its surrounding neighbourhood an appearance and an atmosphere which are neither very bright, healthy, or agreeable. Leaving tho Green by its Northwest gate, and crossing Charlotte-street (in which stands a Roman Catholic convent, and an infirmary for diseases of the eye), we come to London-street, which leads us back to the Cross. Pursuing our way still eastward along the Gallowgate, we reach the infantry barracks, and still further on a spacious horse and cattle market, lying to the North, and occupying an area of 30,000 square yards. Then returning westward along Duke-street, in which are situated the city and county bridewell, or north prison, and the house of refuge, an institution for the reformation of juvenile thieves, we find ourselves in the High-street, a little way above Glasgow College. High-street itself being, as we havo already said, one of tho oldest streets of the city, presents to our view several buildings which testify to its antiquity. From it diverge numerous “closes,” “wynds,” and “vennels,” or, in other words, narrow lanes and culs-de-sac, similar to those which exist in the and narrow Trongate, Bridgegate, King-street, and Stockwell-street, and which are densely inhabited by a poor and dirty population, amongst whom fever and various kinds of infectious diseases, bred by want of proper air, sustenance, and clothing were once very prevalent. These evils are, however, being daily mitigated by the efforts of the corporation, who, as opportunity offers, improve them both physically and morally, so that thw whole condition of th eplace and its inhabitants has undergone, and is still undetgoing, a wonderful change for the better,

The most important buiding it the street is the College or University, which the Hunterian museum behind it. Both these institutions will more fully be described hereafter. For the present, proceeding still northwards up the High Street, we meet with a considerable bend in the road, which here becomes steep and narrow. This portion of it is called the ‘Bell ot the Brae,” and is said to have been memorable for the defeat (a.d. 1300) of the English under Henry Lord Percy of Almviek, by the Scotch under Wallace. This, however, is only a legend, to be found in a l5th century romance, and cannot be accepted as a genuine historical fact. At the top of tho hill are the Rotten-row (in which there is an asylum for indigent old men) to the West, and the Drygate to the East.

The High Church or Glasgow Cathedral and Other Houses of Worship

Glasgow Cathedral by Edward Dayes. Watercolor. Source: Renwick's Glasgow Memorial.

Still proceeding northward, we reach the infirmary and fever hospital, standing upon the site once occupied by tho bishop’s palace, while on the right appears the venerable pile of the High Church, or Cathedral, surrounded by its ancient burying-ground and precincts. This noble building, which is one of the finest examples remaining to us of the early English, or first pointed style of Gothic architecture, stands upon very high ground, and was founded by Joceline, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Melrose, in 1176, upon the spot where there previously stood a church, which was built in 1123, and consecrated to St. Mungo by Bishop John Acliaius in 1130, but was burnt down in 1173. The beautiful crypt was consecrated by Bishop Joceline in the year 1197, and he was also for a long time believed to have built the choir and the lady-chapel, but the truth is, that although they were commenced by him, they were finished by his successors.

The exterior of the Cathedral and two images of the interior (2016). Photgraphs by George P. Lamdow.

This prelate it was who obtained from William the Lion (circa 1180) a royal charter constituting Glasgow a burgh of barony holding under the bishop, and it was not until tho year 1039 that the burgh duties were declared by an Act of Parliament payable to the crown. The bishops also claimed and exercised the right of nominating the magistrates and bailies so late as tho year 1655. But in 1690 a charter of William and Mary conferred upon the city and town council the right of appointing their own magistrates in a manner similar to that which was enjoyed by other royal burghs. It was Joceline also who obtained from King William the charter for the holding of Glasgow fair annually, and described hereafter. For the present, proceeding still northwards up the High-street, we meet with a considerable bend in the road, which here becomes steep and narrow. This portion of it is called the “Bell of the Brae,” and is said to have been memorable for the defeat (a.d. 1300) of the English under Henry Lord Percy of Alnwick, by the Scotch under Wallace. This, however, is only a legend, to be found in a 10th century romance, and cannot be accepted as a genuine historical fact. At the top of the hill are the Rotten-row (in which there is an asylum for indigent old men) to the West, and thc Drygate to the East Still proceeding northward, we reach the infirmary and fever hospital, standing upon the site once occupied by the bishop's palace, while on the right appears the venerable pile of the High Church, or Cathedral, surrounded by its ancient burying-ground and precincts. This noble building, which is one of the finest examples remaining to us of the early English, or first pointed style of Gothic architecture, stands upon very high ground and was founded by Joceline, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Melrose, in 1170, upon the spot where there previously stood a church, which was built in 1123, and consecrated to St. Mungo by Bishop John Acbaius in 1130, but was burnt down in 1175. The beautiful crypt was consecrated by Bishop Joceline in the year 1197, and he was also lor a long time believed to have built the choir and the lady-chapel, but the truth is, that although they were commenced by him, they were finished by his successors. This prelate it was who obtained from William the Lion (circa 118U) a royal charter constituting Glasgow a burgh of barony holding under the bishop, and it was not until the year 1030 that the burgh duties wero declared by an Act of Parliament payable to the crown. The bishops also claimed and exercised the right of nominating the magistrates and bailies so late us the year 105-5. But in 1090 a charter of William and Mary conferred upon the city and town council the right of appointing their own magistrates in a manner similar to that which was enjoyed by other royal burghs. It was Joceline also who obtained from King William the dialler for the holding of Glasgow fair annually, and Thursday markets weekly, together with several other rights and immunities, which raised Glasgow to the position of an influential city, even at that early period of her history.

The length of the cathedral from East to West is 319 feet by 63 feet in width. The height of the nave is 85 feet, of the choir 90, and of the spire, which stands upon a tower, 225 feet. The building is supported by 147 pillars, and has 159 windows, some of which have been very recently restored, as also have been various other portions of the sacred edifice. There are certain indications that the noble structure was once intended to have been cruciform, but there are now no transepts remaining. On the South side, however, is a projection, which was added to the church by Bishop Blackader, (temp. James IV.), and which was for some time used for purposes of burial, but which many, with every appearance of probability, conjecture to have been a transept. If, however, this be so, there is no corresponding projection on the northern side, owing, perhaps, to the circumstance that no one since the time of Blackader was munificent enough to build a North transept. Beneath the choir is the crypt, which is 125 feet in length by 62 in breadth. It is supported upon low arches, springing from sixty-fivo pillars; and it is a very remarkable fact that the piers are of all manner of shapes, both round and angular, and the capitals of the columns vary from the simplest to the most intricate sculptural design. A dim light, admitted by forty small windows, reveals to the spectator the architectural beauties of the place; and it has been asserted by competent authority that this crvpt is unsurpassed in its own peculiar style by any other building of a similar nature elsewhere. In ancient times, until the superstructure was finished, the ordinary' worship of the church was carried on in this crypt. In the episcopate of Blackader, Glasgow was, by a bull of Pope Alexander VI., erected into an archi-episcopal see, and the archbishop became possessed of increased powers, not only ecclesiastical, but civil, as King James IV., who was himself a canon of the cathedral, granted him many additional dignities and privileges.

There are about 200 churches and places of religious worship in Glasgow, belonging to the Established Church, the Free Church, the United Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Presbyterians, Original Seeeders, Independents, Independents not in connection with the Congregational Union, Old Independents, Baptists, Evangelical Union, Church of England, Scottish Episcopalian, Catholic Apostolic Church, Wesleyan Methodists, Wesleyan Association, Primitive Methodists, Congregational Presbyterians, Society of Friends, Universalists, Unitarians, and Roman Catholics. The last named have an immense church, dedicated to St. Andrew, in Clyde-street, besides other places of worship, and two convents, viz. that of the Sisters of Mercy in Abcrcromby-street, and that of tho Immaculate Conception in Charlotte-street.

The Reformation

In 1525 Gavin Dunbar, tutor to King James V., was consecrated Archbishop of Glasgow, and during his tenure of office it was that the principles of the Reformation began to be openly adopted and enforced in the V'. of Scotland. Dunbar died in 1517, and in 1552 James Beaton, nephew of the cardinal of that name, succeeded to the see. This was the last prelate of the Romish Church who held sway at Glasgow, for by this time the Reformation had spread itself so extensively, and its promoters were acting so energetically, that the archbishop saw that it was vain to struggle against events which he had not the power to control, he removed into the bishop’s palace, which immediately adjoined the cathedral, all the valuables which the latter edifice contained; and in 1500 passed over into France, carrying with him the archives of the church, and a considerable quantity of the gold and silver plate, and ornaments belonging to it. These he deposited partly in the Scotch college, and partly in the Chartreaux, in Paris, but the chartulary of the cathedral and other of the MSS. relating to it were saved during the French Revolution, by the Abbe Macpherson, and were by him sent back to Scotland. None of the Protestant bishops did anything to enlarge or beautify the cathedral, which, although it suffered, much during the progress of the Reformation, happily escaped destruction at that eventful period, and still remains to us as a sumptuous monument of the pious munificence of bygone ages.

In 1856 a committee was formed and subscriptions raised for embellishing it with memorial windows of stained glass. These havo been executed at the Royal glass painting establishment at Munich from designs by various artists. There are fortv-two of them in the choir, nave, transept, and crypt, and two more only arc wanting to complete their projected number. They consist of subjects from the Old and Now Testaments, and are the most beautiful and chronologically accurate examples of a series of stained-glass windows ever executed. On the South of the cathedral stands the Barony Church, an unsightly building erected for the use of the congregation which had formerly worshipped in the crypt. Between this and the cathedral lies a portion of the ancient burial-ground, from which a narrow path leads to a bridge commonly known as the “Bridge of Sighs,” the reason of this denomination being that it affords entrance to the Necropolis, or “city of the dead.” It spans a stream called the Molendinar Burn, where the water of the river Molendinar, having been stopped by a dam and collected into a small lake, is just underneath allowed to fall and form an artificial cascade down a steep ravine between 200 and 300 feet deep. This noble cemetery occupies a site formerly known as the Fir Park, which is believed to have been in olden times one of the sacred retreats of the Druids, and now exhibits every variety of sepulchral memorials, from the humblest grave and the simplest headstone to the most spacious vault or the elaborately-carved column or monument. In many of these repose the remains of those whose names are enrolled in the historic records of our country; “heroes of the pen or sword,” whose genius is even now their country’s boast, and who, “being dead, still live.” Among them is conspicuous a column erected to the memory of John Knox, surmounted by his statue. The whole of the Necropolis is divided into walks, which are ornamentally planted, and most carefully kept, after the manner of the cemetery of Père la Chaise, at Paris, and the view of the city and the country by which it is surrounded is at once curious and picturesque.

On the North of the stands the blind asylum, and nearly opposite to it that for the deaf and dumb, and still further on the Barony poorhouse and New Town hospital. Not far from this, in a north-westerly direction, are the important chemical works of St. Rollox, the lofty brick chimney-stalk of which is, rising as it does to a height of 450 feet, a very conspicuous object; and about half a mile further on is the Sight-hill Cemetery, which, like the Necropolis, is tastefully planted and laid out, and abounds with many graceful and magnificent sepulchral monuments. This is the extreme point in this direction to which any buildings properly belonging to the city can be said to extend. Before quitting this portion of it, however, it will be useful to give some the city can be said to extend.

University of Glasgow

University of Glasgow. South front, seen above Kelvingrove Park. Sir George Gilbert Scott, with the Bute and Randolph Halls completed after his death by John Oldrid Scott and Edwin Morgan, 1866-86, and the tower and spire added by John Oldrid Scott, 1887-1891. Local stone with Kenmure freestone dressings, and some columns of red sandstone and pink granite. Gilmorehill, Glasgow.

Before quitting this portion of it, however, it will be useful to give some account of the Glasgow University or College, which, as has been already observed, stands on the eastern side of the High-street. Returning, then, from the cathedral, the passenger crosses the end of George-street, in which is situated Anderson's university, with the High School standing in the rear of it (both of which will be adverted to hereafter), and arrives at the principal educational establishment of the city. The University of Glasgow was founded by Bishop William Turnbull in 1450, in virtue of a bull obtained by him from Pope Nicholas V., at the express desire of James II., and in 1451 [sic] a body of statutes was promulgated, and the university opened for the prosecution of theological and legal studies, and for the cultivation of the liberal arts, and a faculty was granted for the conferring of degrees. A deed constituting it a body corporate was drawn up, and the corporation was to consist of a chancellor, a rector, a dean, a principal, the professors, and the students. At first the university was very poor, and having no buildings of its own, was allowed the use of a house near the cathedral; but in 1459 James Lord Hamilton conveyed to the principal and regent professors of the faculty of arts a tenement in High-strcet, and 4 acres of land bordering on the Molendinar, on certain conditions declared in the deed of conveyance, one of which was that he and his wife Eupliemia should be commemorated as the founders of “Lord Hamilton's College.”

The University of Glasgow. W. L. Leitch. Wood engraving. From Blackie’s Imperial Gazetteer. This drawing depicts the university as described in the text and obviouly not Scott’s buildings as shown in the photographs.

The present college stands on the site of these buildings, and subsequently received considerable additions. From the period of the Reformation till the year 1577, it maintained a severe struggle for its very existence, but in that year James VI. granted it a fresh charter of constitution and increased revenues, which together with gifts from private individuals, once more raised its statu*, and it was restored to a comparatively flourishing condition. At the restoration of Charles II., however, it was, owing to the establishment of episcopacy in Scotland, once more deprived of a considerable portion of its revenues, and it was not till 1693 that it ultimately recovered the various shocks it has received since its establishment, and was placed on a permanent footing. In that year all the Scotch universities received a grant of £300 per annum out of the bishop’s rents, and this, added to gifts from the crown and benefactions from private individuals, assured its financial independence, and various statutes and laws for its government, enacted cither by public commission or the body corporate itself, have raised it to the present respectable position which it occupies among the educational establishments of the kingdom. The institution is in its nature somewhat of an imperium in imperio, consisting of the University, which is that corporate body in which is vested the power of granting degrees, and the College, which is an incorporation within the university, endowed for the purpose of educating young men.

Left: North front with the Main Building and entrance to the Visitor Centre. Right: Main entrance, University of Glasgow.

The officers and governing body are—a chancellor, whose functions are almost entirely nominal; a lord rector, who acts, as it were, as the chief magistrate of the university, and is the guardian of all its rights and privileges; a principal, who is the resident director of the college, and enforces the observance of a due attention to the rules enacted for the religious, moral, and educational training of the students. The appointment of this officer lies with the crown, and his position is one of very great responsibility. He presides at the meeting of the faculty, at which he only has a casting vote. The Dean of Faculties is elected by the Senate, his duty being to give directions concerning the studies to be pursued in each faculty. The professors are divided into regius and college professors, according as they are appointed by the crown or the governing body of the university. Their powers are varied according to the posts which they occupy, and they teach and lecture in tour distinct schools of theology, arts, law, and medicine. The students for some few years have averaged from 900 to 1,000 in number. Those who study in the Latin, Greek, ethical, logic, and natural philosophy classes, are called the togati, and wear a red gown, being regarded, as it were, upon the foundation.

A bas relief over the entrance to the Kenilgrove Museum and two images of the interior (2016). Photgraphs by George P. Lamdow.

The non-togati are exempt from all discipline, except that of attendance at their classes, and the obligation of general good behaviour. They are divided into four classes, or ‘nations,” according to the parts of the country from good behaviour. Thoy are divided into four classes, or “nations,” according to the parts of the country from which their members come. Thus, those from Lanarkshire, Renfrew, and Dumbarton form the natio Glottiana, or Clydesdaliae; those from the North of the Forth and foreigners, the natio Tranforthana, or those from the Lothians, Stirlingshire, the towns East of the Urr, England, and the British colonies, the natio Loudoniana; those from Argyleshire, Ayrshire, Galloway, the Western Islands, Lennox, and Ireland, the natio Loudoniana. These “nations” vote at the Comitia or general meetings of the college for the election of the rector. Upon these occasions, which are annual, there is great excitement among the students when rival candidates for the rectorship aro equally, or nearly equally, distinguished for their birth, talent, or any other circumstance which may give them a claim to hold this honourable office. Among the names of the eminent men who have filled the chair during the present century may be mentioned those of Lord Jeffrey, Lord Brougham, Campbell, the poet, the Marquis of Lansdowne, Lord Cockbum, the Earl of Derby, Sir Robert Peel, Earl Russell, Lord Macaulay, Sir Archibald Alison, Bart., the Earl of Eglinton, the Duke of Argyll, the Earl of Elgin, and Viscount Palmerston.

The exhibitions from Glasgow University are those founded by John Snell, for the purpose of upholding episcopacy in Scotland. They are worth £132 a year each; and from another exhibition, founded by John Warner, Bishop of Rochester (1637-1630), £15 is generally added, so that the Snell exhibitioners proceed to Balliol College, Oxford, with an allowance of about £150 per annum, tenable for ten years, and forfeited only in case of marriage, any very valuable preferment, or expulsion from the university of Oxford. There are also twenty-nine foundation bursaries, varying in value from about £5 to £50 per annum, and tenable from four to six years; with valuable prizes, which are distributed annually at the Comitia, for merit in the several classes.

The university library contains upwards of 70,000 volumes, and additions are being constantly made to this already extensive and important collection. The college itself externally presents to the eye a sober and scholastic appearance. It consists of a long range of buildings on the East sido of the street. Upon entering at the principal gate, over which aro the arms of Charles II., in the first of the fivo quadrangles or courts of which the interior consists the visitor will notice a fine old staircase, and at the northern extremity a gateway leading to an area, in which stands the houses of the professors. Although the buildings of the university are well adapted for their purposes, it cannot, as a whole, lay claim to architectural harmony or beauty, because as the older portions of the edifice have from time to time been necessarily replaced or restored, they have been reconstructed, either partially or wholly, in a style different from that of the original buildings, and even in some instances from each other. The genius loci, however, as far as the university is concerned, will soon disappear altogether from this part of the city, for the authorities have prudently purchased the magnificent site of Gilmore Hill for the sum of £65,000, and thither the college and all its belongings will bo transferred at the earliest possible date. At the rear of the college stands the Hunterian museum and institution, founded in 1781 by Dr. William Hunter, of Kilbride, who bequeathed to the university his valuable artistic, literary, and antiquarian collection, with a legacy of £8,000 for the purposo of erecting a repository for then. The money value of this collection is estimated at nearly £150,000, and the public are admitted to view it upon the payment of the fee of one shilling.

Other Educational Institutions

Besides the college, Glasgow posesses another valuable educational institution in the Andersonian University, situated in George-street. This was founded in 1796 by Dr. John Anderson, professor of natural philosophy in the college. It received a charter of incorporation from the city magistrates and council, audits functions were originally restricted to the teaching of physical science. In I860 the well-known Dr. Birkbeck, who was professor of natural philosophy here, instituted a class expressly for mechanics, and this it is generally thought was the origin of those ”mechanics’ institutions” which have since been so common throughout the kingdom. In the course of time a library, museum, and class-room wero founded, and classes formed for morning and evening study in the various branches of a literary and scientific education, carried on under able and distinguished professors and teachers. The mechanics’ institute, which is situated in Bath-street, was founded in 1823, and possesses a good library of about 6,000 books, a commodious reading-room, and a small but valuable collection of philosophical and mechanical tools and apparatus. On its pediment stands a colossal statue of the renowned James Watt.

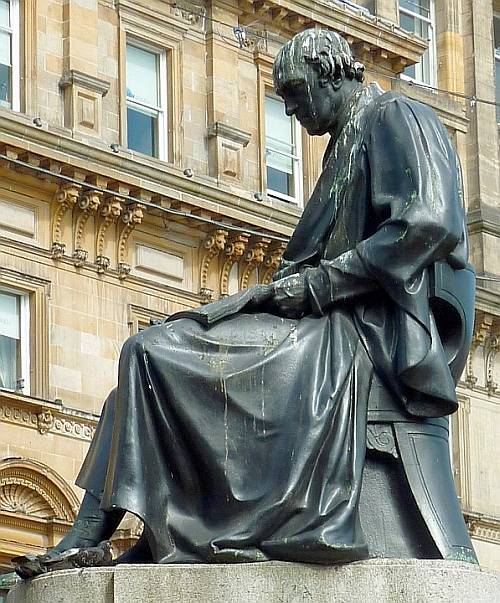

James Watt. Francis Chantrey 1832. Bronze on a Devonshire granite pedetal. George Square, Glasgow.

The most ancient educational establishment next to the university is the High school in Montrose-street. It is under the management of certain members of the town council, and education in classics, mathematics, the modern languages, and the various branches of a commercial or general education, are taught by competent masters at very moderate fees. Neither this nor any of the public schools in Glasgow are “boarding” schools, the pupils merely going there to attend their several classes, and living wherever they themselves or their friends may choose. Besides the High school there are several other seminaries, such as the Normal Seminary for the Established Church in the Cowcaddens, and that for the Free Church in the same district; the collegiate school on Garnet Hill, and several others both for boys and girls, and the Free Church College, near the West End Park, for the training of students in theology. In fact, Glasgow abounds with educational establishments, public and private, adapted to the various wuuts of the community, from the highest to the lowest class, and there are very many resident private teachers in every part of the town lor music, dancing, drawing, languages; in fact, for all the accomplishments and requirements of a refined and liberal education. The Atheneum in Ingram-street is an establishment of a mixed character, consisting of a library, a reading-room, and rooms for educational classes and lectures. The library contains upwards of 8,001) volumes, and admittance to the reading-room is gained by an annual subscription of £1 Is., while the payment at the Exchange reading-room is £2 10s., and that at the Tontine £1 annually. There is, however, now a plan under the consideration of the town council which will no doubt sooner or later come into operation, for the establishment of a free public library. It is in contemplation to organise all the chief literary societies of the city by means of a central union, and by this federalisation to establish a public museum and library where readers are to be admitted somewhat upon the principle of the British Museum, and where high class lectures are to be given annually, on a plan similar to that which is carried out at the Royal Institution in London.

he Western Club Glasgow. c. 1890.

The principal club in Glasgow is the Western, which is at the junction of Buchanan-street and St. Vincent-street. Beyond the Western club is St. George’s church, from which runs West George-street, and parallel with it Regent-street, Bath-street, and Sauchiehall-street, all leading to the newer and more magnificent skes of the city. The eastern portion of the last named street is called Cathcart-street, and opposite to the end of it the parliamentary road runs eastward, and after passing by the city parish poor-house, or town hospital, connects this portion of the city with those previously described as lying in the neighbourhood of the cathedral and St. Rollox. Returning along Sauchiehall-strcet, which is a magnificent thoroughfare 60 feet wide, consisting of fashionable shops and spacious dwelling houses, on the right rises a high piece of ground called Garnet Hill, built over with commodious streets and houses, principally the residences of private families, and affording a view to the North of the Forth and Clyde canal, and Port Dundas, and in the further distance of the peaks of the Perthshire and Argyleshire mountains. Continuing our course still westward, we notice Woodside-crescent, Claremont-terrace, and many other splendid terraces, squares, and crescents, which have been already mentioned as the residences of the wealthiest classes of the citizens. Adjoining the western portion of these magnificent ranges of buildings, some of which are as elegant as they are substantial, and possess all the latest improvements of modern architecture, is the estate of Kelvin-grove, on which, owing to its picturesque situation and scenery, has been tastefully laid out a public park and promenade. To the North, on the banks of the Kelvin, and skirted by the Great Western road, is the Botanic Garden, to the South of which are the observatory and the residence of the professor of astronomy. The professor of botany and his pupils have free access to the garden at all times of the year; and it is also thrown open to the public during the week of Glasgow fair.

Still farther on, along the Great Western road, and at a distance of about 3 miles from the city, is the Gartnavel lunatic asylum, which was founded in 1842, and cost the sum of close upon £80,000. Its management and internal arrangements are admirable, and both pauper and private patients are admitted to partake of its benefits.

Old Bridge and Houses at Partick [outside Glasgow] by William Simpson. Watercolor. 1849[?]. Source: Renwick's Glasgow Memorials, frontispiece.

To the South is Partick, which, although it is a post town and burgh of barony in itself, has been so united to Glasgow by the Sandyford extension, that it may be now regarded as almost forming part of the city itself. It stands at the confluence of the Kelvin and the Clyde, which from this point up to Glasgow Green, presents an appearance of ceaseless enterprise and activity.

Glasgow’s Bridges

It is, indeed, to this noble river that Glasgow is, in a great measure, indebted for her national importance; and before describing its various capacities, it may be observed that it is crossed by five bridges, which connect the northern and southern sides of the city at various points between the Broomielaw, or quay, and the Green. The uppermost of these is at the bottom of the Salt Market, it leads to Crown-street on the opposite side of the river, and is called Hutcheson’s bridge. The second, at the bottom of Stockwell-street, was in olden times the only means of communication between the northern and southern banks of the river. It was built circa 1345-50, and remained pretty nearly in its original state till 1770. In that year, and again in 1821, additions and alterations were made in it, but it became so insecure, that in 1850 it was found necessary to replace it by a new bridge.

The Victoria Bridge. James Walker (1781-1862). 1851-4. Sandstone faced with Irish granite. From Stockwell Street to the south bank of the Clyde.

The present structure, which is called the Victoria bridge, consists of five arches, the centre of which has a span of 80 feet, with a rise of 10 feet 6 inehes. Its length is about 415 feet, and the width of its roadway is GO feet. It is built of remarkably strong white sandstone faced with Kingston granite, and was erected at a cost of £40,000.

The third bridge connects Maxwell-street on the northern with Portland-street on the southern hank. It is an iron suspension bridge, for the use of foot passengers only, and as the funds necessary for its erection were principally supplied by a private individual, a toll of a farthing a head is taken from those who cross it. But by an Act of Parliament it is to be toll free as soon as a sufficient sum shall have been collected to defray its original cost.

Broomielaw Bridge, 1850 by Sam Bough. Watercolor. Source: Renwick's Glasgow Memorials.

The fourth, or lowest bridge, lies at the foot of Jamaica-street, and is called the Broomielaw, or Glasgow Bridge. It has seven arches, is 560 feet long, has a roadway of 60 feet in with, and was built at a cost of £37,000. A charge is made at all the Glasgow bridges for vehicles, horses, and live-stock passing over them, but they are all, with the exception of the Maxwell-street bridge, free to pedestrians. Besides these bridges, there is a foot-passenger bridge at the Higher Green, near the Royal Humane Society’s receiving house. This was built for the accommodation of the operatives residing in the Northeast portion of the city, who are employed in the numerous mills, print works, and factories which stand on the south-eastern, or Gorbals side.

The River Clyde and Its Importance to Glasgow

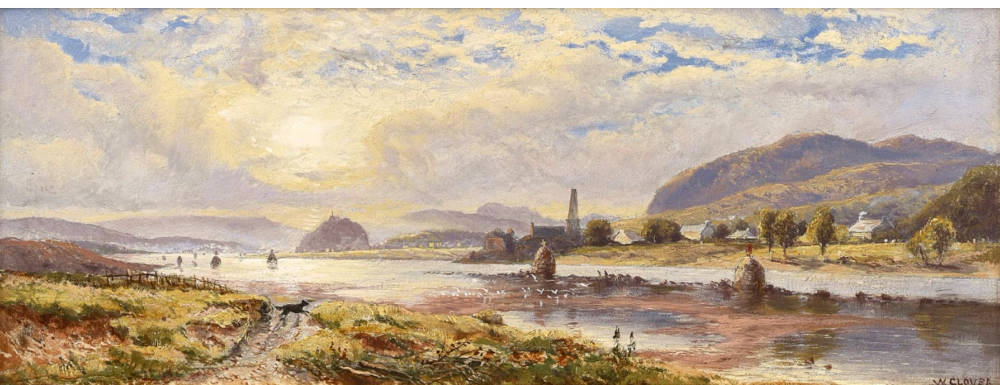

The Clyde. 1867 by William Glover (1848-1916). Oil on board, 9 x 21 inches. Signed and dated '67.

The Clyde at Glasgow was originally a narrow channel, with scarcely depth enough for even small boats to navigate it. In 1566 the first attempt was made to deepen it, and clear the stream of some of its obstructions, and this was to a certain extent effected; but the work proceeded so slowly, that in 1662 the town council, finding how important it was that shipping should be able to come as near the city as possible, purchased some land about 18 miles down the river, and there laid out quays, a harbour, and a graving dock. This place, called Port Glasgow, is still in use for shipping, but as it was found to be inconvenient on account of its distance, a quay was built in 1688 at the Broomielaw for the purpose of landing goods winch were brought up the river in small flat-botlomcd boats — for which alone it was navigable — from Port Glasgow. At length, in 1758, upon the report of John Smeaton, the celebrated engineer, an act was passed for improving the river; but nothing of any importance was effected till 1775, when it was deepened sufficient to allow vessels drawing nearly 7 feet of water to he moored off the Broomielaw.

From this time until 1812 the navigation up to Glasgow remained much in the same state, but in that year it received a great impetus in consequence of the placing on the river of the first steam vessel which had ever been constructed. Whatever may be the claims of others to have been the originators of the idea of propulsion by steam, certain it is that Henry Bell, a native of Torplhichen, in Linlithgowshire, was the first who brought it into any practical use for the purposes of navigation. In January, 1812, Bell constructed a steam vessel 40 feet in length, and with an engine of three-horse power, which was capable of ascending the river against wind and tide at the rate of about 6 miles an hour.

From that time up to the present, methods taken for improving the navigation have been earned on in an unremitting and highly scientific manner; and the consequence is, that ships of nearly 2,000 tons are able to lie in the harbour, and at the Broomielaw vessels of from 800 to 1,000 tons may often be seen receiving or discharging their cargoes. The line of quays on the North and South side of the river extend to about nearly 2 miles in length, and in addition to these there is a fine stone wharf 500 feet in length, for the accommodation of smaller craft above the Broomielaw bridge. The piece of water lying between this latter named bridge and the Victoria is denominated the “inner,” as that lying below it is called the “outer harbour.”

Large improvements and extensions of these already important works aro constantly going forward, under the direction of the Clyde trustees, who are a body formed by members chosen out of the corporation, the trades’ and merchants’ houses, the chamber of commerce, and the shipowners of the city. It is their duty to manage everything connected with the river, such as its finance, the regidations lor the sailing of vessels for business or pleasure, and the various other matters which naturally attach themselves to so important an office.

There is, perhaps, no other river in the world which offers more inducements to the pleasure-seeker than the Clyde, and the consequence is, that the harbour and quays present an appearance, more especially in the summer months, not only of commercial activity, but of the most amusing bustle and excitement. Hundreds of steamers, conveying the citizens to their country mansions on the coast, excursionists and tourists on their various trips to the beautiful spots in the immediate vicinity of the city, or travellers and emigrants to foreign countries and more distant scenes, pass constantly to and fro; and to any ono who sails from Glasgow down to Greenock, the vast numbers of ship-building and engineering establishments which extend along the shores, the forests of masts on the river, the fleets of sailing and steam vessels and small craft constantly moving up and down the stream, will afford constant food for wonder and amusement. In 1863 the number of sailing ships arriving at the port of Glasgow was returned at 3,148; that of steamers at 10,655, their tonnage collectively being estimated at. about 1,386,038 tons; while the harbour dues amounted to about £120,000, of which sum nearly £95,000 has been expended by the trustees during the past year in dredging and similar operations for deepening and clearing the channel, in addition to the enonnous sums which aro also expended for new works upon the banks. Another of the important elements in the prosperity of Glasgow is that of the enormous sums which are also expended for new works upon the banks.

Another of the important elements in the prosperity of Glasgow is that of its capabilities for the acquisition of coal and iron, these minerals coming in great quantities from the wholo district of western Scotland, where they abound, and the latter of them being dug and manufactured within a few miles round the city. Thus great facilities are given for those branches of industry in which iron is an important element, and the enormous iron shipbuilding establishments which now exist upon the Clyde have all been called into existence by the ease with which iron is acquired and worked almost upon its very banks. During the last year there were 31 sailing vessels all of iron, and 4 of wood and iron combined, launched on the Clyde, besides 67 screw steamers all of iron, and 2 of iron and wood. In addition to these there were 38 iron paddle-steamers, 1 iron ram, 2 iron steam dredges, and a vast quantity of small tugs and craft of various kinds. The tonnage of the vessels launched on the Clyde during the year 1803 amounted to 124,000, while that already in construction since the 1st January, 1864, considerably exceeds 100,000 tons, so that it is evident that the skill and enterprise which have already made the Clyde what it is, are still busily at work adding each year to its capabilities; and there are at present (autumn, 1804), 15 deep-sea steamers being built for the purpose of blockade-running. The vessels which arrive annually in the Clydo amount to nearly 20,000, with an aggregate tonnage of nearly 2,000,000 of tons, and the customs duties collected during 1863 amounted to £983,990 10s. 3 d.

Independently of the iron which is consumed for the shipbuilding purposes of Glasgow, the cast iron which is produced there is no less astonishing for its quantity, than it is famed, both at home and abroad, for its excellent quality. The aggregate of that shipped for railway purposes, and for articles of domestic use, amounted during the past year, without counting that used at home and that sent by rail, to close upon 85,000 tons, the whole quantity of iron produced amounting to 1,100,000, and that shipped away from Glasgow to 1,105,000 tons.

Before the breaking out of the American war, the cotton trade was one of the great staples of the wealth of Glasgow, and about fifty mills for spinning yarn and thread were in full operation. Besides these there were many cotton-weaving mills and machines, and a vast population of haml-loom weavers, and various works tor the manufacture of worsted, linen, silk, and mixed fabrics. To these branches of industry may be added linen, worsted, and carpetweaving, the embroidery of muslin with needles, and that of silk upon woollen stuffs, in which latter trades more than 10,000 women aro kept employed—cotton printing, bleaching, and dyeing.

In addition to all this, there are many other manufacturers in Glasgow who derive large incomes from businesses which although they do not stand prominently forward, nevertheless are carried on to a large extent, and form a considerable item in the prosperity of the city. Such, for instance, are the glass factories and the potteries, where not only the coarse red clay of the district is worked for the supply of the common articles of domestic use, but also the finest kind of porcelain is made from clay expressly imported lor that purpose, and upwards of a million of pipes aro turned out weekly for the uso of tobacco smokers. We may also add to these the manufacture of tile drains, and all kinds of earthen bottles and vessels for containing the chemicals and spirits which Glasgow produces in such large quantities, upwards of 3,010,000 gallons of the latter having been distilled there in the course of the year. There are also extensive sugar refineries, timber yards, ale and porter breweries, boot and shoe factories, clothing establishments; in a word, every article of human industry is manufactured here, and meets with a ready mart, not only for home consumption, hut also for the vast export trade which is carried on at the port. From all this it results that Glasgow, possessing as she does within herself so many local branches of industry, and such various means of employment for her citizens, is still in a most thriving condition, notwithstanding the depression of the cotton trade; and there is every reason to believe that her progress, owing to the capabilities which she still enjoys for improvement, will he almost as marvellous in future years as it has been in those that have gone by.

The newspaper press of Glasgow employs a considerable number of hands; the principal journals are the North British Daily Mail, the Herald, and the Morning Journal, published daily. The Citizen, the Saturday Evening Post, &c., appear weekly. They are all most respectably edited and conducted, and fully deserving the support which they respectively enjoy.

Glasgow’s Water Supply

Tho town is supplied with water from Loch Katrine—that lovely lake in the Trossaehs, rendered for ever memorable by the minstrelsy of Sir Walter Scott—which lies at a distance of 31 miles from the city. The old water-works, which belonged to a joint stock company, were bought up by the corporation for the price of £674,000—only that portion of them which is situated in the Gorbals on the S. side of the river being left in operation—and the new works were commenced in 1856 by Bateman, the engineer appointed to carry them forward. In 1859 they were completed, and were opened by the Queen on the 14th October of that year. They bring into Glasgow 18,500,000 gallons of the purest water daily from an elevation of 360 feet above the level of the sea, by the mere force of gravitation. The cost of their construction amounted to £918,000.—There nro six separate police establishments in the city, each under a local superintendent, who is again in his turn under the superintendent of the central district, and there is also an efficient fire brigade.

Glasgow also possesses a public washhouse, and a gymnasium, situated upon the Green near tho suspension bridge, and there havo lately been built public eating-rooms, at which refreshments can he obtained of the best quality, and at a very moderate price, by the working classes. Those establishments, although the articles supplied at them nre charged at a very low tariff, are found not only to be self-supporting, but even to return a small profit to their projectors, and the example set by Glasgow in originating them has been copied, and will, it is to be hoped, be yet still further copied, in some of the large towns in England.

The exterior and interior of Glasgow Central Station, which was not constructed until 1876-79, a few years after the Gazetteer article by a series of Scottish engineers. Click on images for more photographs and a history of the station

The railway termini in Glasgow are situated as follows:—The Edinburgh and Glasgow in St. George's-square; the Caledonian at the extreme end of Buchanan-street; tho Greenock, Ayr, and Paisley on the S. side of the river, at the foot of Glasgow bridge. A scheme has just been set on foot, and has received the sanction of parliament, for uniting all these railways at a general terminus on the East side of St. Enoch’s-square, and the site of the college is to he converted into an immense goods station. The municipal government of tho city is in the hands of a lord provost, 8 bailies, a dean of guild, a deacon-convener, and 37 common councillors, who are elected by the £10 ratepayers.

The Arms of the City of Glasgow, or the City Crest

According to to the city’s official site, “The City of Glasgow had no single official armorial bearings until the 19th century. There were at least three official seals in use and a patent was granted by the Lord Lyon in 1866. The first seal on which all the emblems are represented together is that of the Chapter of Glasgow used from 1488-1540, but it was not until 1647 that they appeared in something like their present combination on a seal. ”

The arms of the city of Glasgow are very peculiar. They consist of a tree with a bird perched on one of tho branches, and having on ono sido of it a bell, and on the other a salmon with a ring in its mouth, tho motto being “Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the Word.” This coat and legend arc said to have arisen from events in tho life of Kentigern, the son of Ewan Eufurien, King of Cumbria, who, having devoted himself to a religious life, took up his abode in Glasgow (a.d. 580). His life was so holy that he obtained the reputation and appellation of a saint, abode in Glasgow (a.d. 580). His life was so holy that he obtained the reputation and appellation of a saint, and although his own name was Kentigern, he received the sobriquet of Mungo, by which title he is more commonly known. He is said to have been so great a favourite with his preceptor, Bishop Servun, that the latter was in the habit of addressing him as Mongah, which in Celtic signifies “beloved friend,” and this familiar appellation was the one by which he became eventually known, on account of tho benefits he conferred upon those among whom he lived. St. Mungo had not long settled in Glasgow before he was driven away from it by the heathen king of Cumbria, and took refuge in Wales, where he founded the see of St. Asaph. Upon his return to Glasgow he began to preach to the people, and such a multitude collected that what he said only reached those who were nearest to him. A miracle, however, enabled all the crowd to hear his discourse, for the ground on which lie stood became suddenly elevated into a small hillock, and thus everyone who was present both saw the saint and heard his words distinctly.

With regard to the arms of Glasgow, the tree is said to have originated from the fact that once, when the lamps in the monastery of Culross were suddenly extinguished, St. Kentigern broke a large frozen bough from a neighbouring tree, breathed upon it, and it immediately became ignited and broke forth into vivid flame. The bird perched on the bough represents a tame robin which was the favourite of St. Servan at Culross; but having been accidentally killed and torn to pieces, its limbs were re-united, and it was restored to life by St. Kentigern. Tho salmon with tho ring commemorates the following event:—The Queen of Cadyow had a ring presented to her by her husband, as a token of his atfection. This ring she unfortunately chanced to lose. The king, suspecting her to have given it away, was about to put her to death, when in her distress she applied to the saint, and begged his prayers for its recovery. St. Kentigem agreed to intercede for her, and alter his devotions, he went to walk upon the banks of the Clyde. While there he observed some men engaged in fishing, and desired that the iirst fish taken should bo brought to him. This was accordingly done, and upon opening the mouth of the salmon, the ring which the queen had lost was found there, and restored to her by the saint. The bell represents a bell that was brought from Rome by St. Kentigern. It was called St. Mungo's bell, and was tolled upon the death of any of the brethren, to warn the citizens to pray for the soul of the departed. It was preserved up to the time of the Reformation, but was carried away by the Iconoclasts and those who destroyed so many precious works of religious art at that period.

This account, however, is of course fabulous. The tree in all probability typifies the forest which surrounded the old portion of the city; the bell the cathedral; the ring the episcopal dignity which Glasgow enjoyed; and the salmon the abundance of that and other fish which was at that early period taken in tho Clyde. The continually increasing wealth and population of Glasgow are daily adding to its resources and its extent. The old buildings and the densely inhabited portions of the city are undergoing constant improvement, and its institutions of every kind are not only liberally endowed and supported, but in many instances afford examples of economic administration combined with great usefulness, which might with advantage be imitated by the managers of similar establishments in other cities and towns of tho United Kingdom. The chief magistrate of Glasgow is styled the “lord provost.” The property of the corporation is very extensive, and arises from feu-duties, bazaar-ients and dues, rents of seats in the Established Church, and various miscellaneous sources. Its amount is about £20,000 annually.

Fairs are held in various parts of the city for live and dead stock on certain days in every month except in August, September, October, and December; and the fast days appointed by the Estab-month except in August, September, October, and December; and the fast days appointed by the Established Church are kept on the Thursday before the second Tuesday of April and the Thursday before the last Tuesday of October.

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer; a General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1855.

The National gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland. Ed. N.E.S.A. Hamilton. London: Virtue [1868]. V, 102-08. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of Illinois Library. Web. 5 July 2022.

Last modified 7 July 2022