Near the beginning of the second volume in The Stones of Venice, Ruskin draws upon his brilliant word painting bring us to Santa Maria Assunta:

Seven miles to the north of Venice, the banks of sand, which near the city rise little above low-water mark, attain by degrees a higher level, and knit themselves at last into fields of salt morass, raised here and there into shapeless mounds, and intercepted by narrow creeks of sea. One of the feeblest of these inlets, after winding for some time among buried fragments of masonry, and knots of sunburnt weeds whitened with webs of fucus, stays itself in an utterly stagnant pool beside a plot of greener grass covered with ground ivy and violets. On this mound is built a rude brick campanile, of the commonest Lombardic type, which if we ascend towards evening (and there are none to hinder us, the door of its ruinous staircase swinging idly on its hinges), we may command from it one of the most notable scenes in this wide world of ours. Far as the eye can reach, a waste of wild sea moor, of a lurid ashen grey; not like our northern moors with their jet-black pools and purple heath, but lifeless, the colour of sackcloth, with the corrupted sea-water soaking through the roots of its acrid weeds, and gleaming hither and thither through its snaky channels. No gathering of fantastic mists, nor coursing of clouds across it; but melancholy clearness of space in the warm sunset, oppressive, reaching to the horizon of its level gloom. [10.17]

In the course of relating the history of Venice and its neighboring islands, Torcello and Murano, Ruskin explains how the settlers of Venice sought a refuge from the ravages of wars on the mainland of Italy. Of this church he therefore emphasizes that “it has evidently been built by men in flight and distress, who sought in the hurried erection of their island church such a shelter for their earnest and sorrowful worship as, on the one hand, could not attract the eyes of their enemies by its splendour” (10.20). For this reason, “there is visible everywhere a simple and tender effort to recover some of the form of the temples which they had loved, and to do honour to God by that which they were erecting, while distress and humiliation prevented the desire, and prudence precluded the admission, either of luxury of ornament or magnificence of plan. The exterior is absolutely devoid of decoration, with the exception only of the western entrance and the lateral door, of which the former has carved sideposts and architrave, and the latter, crosses of rich sculpture” (10.21). Sounding like St. Augustine, who described all our lives as voyages, pilgrimages, back to God, Ruskin sees this church as the perfect, appriopriate, expression of Christianity, for, as he tells us, “I am not aware of any other early church in Italy which has this peculiar expression in so marked a degree; and it is so consistent with all that Christian architecture ought to express in every age (for the actual condition of the exiles who built the cathedral of Torcello is exactly typical of the spiritual condition which every Christian ought to recognise in himself, a state of homelessness on earth” (21).

Approaching Torcello on a bleak damp day.

In the second volume’s Appendix 5, Ruskin explains that “It is a disputed point among Venetian antiquarians, whether the present church be that which was built in the seventh century, partially restored in 1008, or whether the words of Sagornino, “ecclesiam jam vetustate consumptam recreare,” justify them in assuming an entire rebuilding of the fabric. I quite agree with the Marchese Selvatico in believing the present church to be the earlier building, variously strengthened, refitted, and modified by subsequent care; but, in all its main features, preserving its original aspect, except, perhaps, in the case of the pulpit and chancel screen” (10.445).

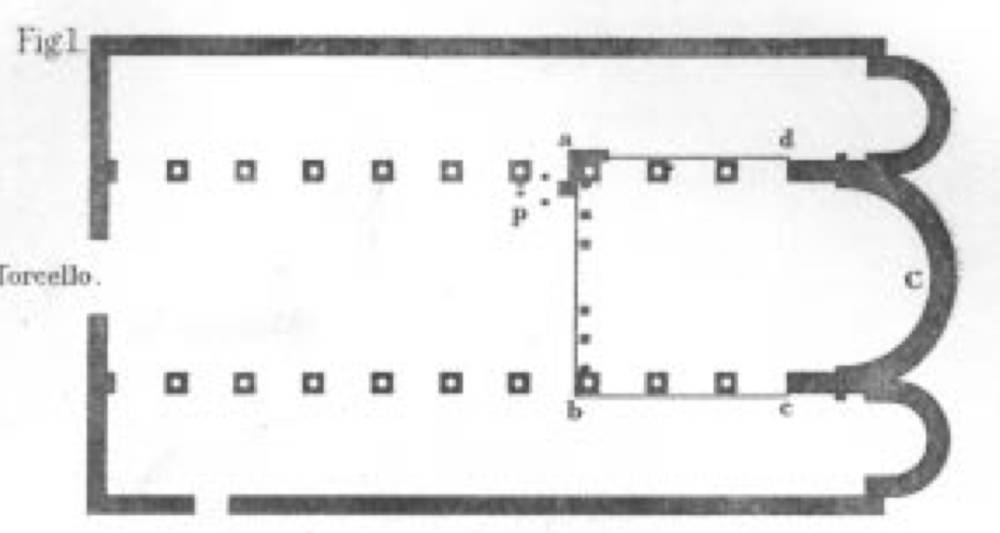

Right: Ruskin’s groundplan of the church.

More of Ruskin's Venice

- St Mark’s Cathedral

- The Palazzo Ducale, Venice

- The Scuola de San Rocco

- Palazzi

- On the Grand Canal

- Leaving the Grand Canal

- On the way to Venice from the mainland

- Venice: Details and Corners

Photographs 2020. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ruskin, John. The Works. Ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. “The Library Edition.” 39 vols. London: George Allen, 1903-1912.

� �

Last Modified 26 March 2020