Photograph top left by George P. Landow, October 2000; photograph of Regent Street façade by "ramson" at Flickr, kindly made available on the Creative Commons licence, and slightly modified here for perspective; photograph of the Salviati grave by Robert Freidus. Remaining photographs and image download by the author, March 2016. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print document. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Salviati in Venice

Two views of the Palazzo Salviati, on the Grand Canal, Venice. This building of 1924 proudly advertises on its decorated façade the mosaic-work for which the family firm of Salviati had, by now, long been celebrated.

Glass-making has, of course, a very long history. It goes back at least as far as the third millenium BC, while the art of glass-blowing was developed by the Romans as early as around 50 BC. "But it was in Venice — specifically, the small island of Murano — where the craft truly developed, flourishing throughout the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries" (Sanford). After that, however, the local industry went into decline. Charles Locke Eastlake, an important art historian and critic who later became Keeper of the National Gallery, tells us that by the nineteenth century "this national art had degenerated into a trade which produced little more than glass beads and apothecaries' bottles" (265). Certainly, by the time John Ruskin visited Murano, the whole place was in the doldrums. In the second book of the Stones of Venice (1853) he could still see signs of its traditional activity, in "the cloud which hovers above the glass furnaces of Murano" and the sight of "various workmen of the glass-houses sifting glass dust upon the pavement," but he found such activity to be "one of the last signs left of human exertion among the ruinous villages" all around (II: 30).

Change, however, was round the corner. Surprisingly, the instrument of this change, Antonio Salviati (1819-1890), had no background in glass-making. Born in Vicenza in the the north, and trained as a lawyer, he became fascinated with glasswork while practising his own profession in Venice. In 1859 he founded the new company which bore his name in collaboration with the skilled glass-maker Lorenzo Radi (1803-1874), and brought to the enterprise, in John Sanford's words, "his good art instincts, marketing skills and public-relations savvy." With these qualities, and the pool of traditional skills which still remained among the local people, he was able to rejuvenate the whole Venetian glass industry.

Close-up of the Palazzo's mosaics, the central panel showing courtiers and others offering tributes to the goddess or muse of art, holding, from left to right, a stemmed bowl in red, the most costly of colours to produce; an elaborately framed mirror; a platter or charger; and a large icon with a gold ground. Below are four artisans at work, two of them women applying decorative work. Of the men, one is a draughtsman, and the other, the muscular man on the far right, is a glass-blower.

Ruskin was entranced by the mosaics of both Torcello (another island in the Venetian lagoon) and Murano, with their beautifully decorated houses of worship. The Cathedral of Santa Maria Asunta on Torcello is a particularly brilliant example of Venetian-Byzantine artistry. Then there was the world-famous St Mark's itself, with an array of superb mosaics even on its façade. Architects in England had already grown interested in the use of colour — witness Matthew Digby Wyatt's lecture of 1850, "On the Polychromatic Decoration in Italy from the 12th to the 16th century" — and his recommendation that "a large flat surface ... best of all surfaces, admits of ornament" seemed an open invitation to mosaicists (qtd. in Sladen 81). So Ruskin's enthusiasm came at exactly the right time, and had a profound effect. It inspired various architects and artists to follow in his footsteps, to see such wonders for themselves. The most important of these was Edward Burne-Jones, who went out to Italy with him in 1862. Burne-Jones revelled in Venice's novel way of life and its water-borne transport, drawing avidly whilst there. Despite an apparent susceptibility to malaria which alarmed his wife, who had accompanied him, he described Venice as "Heaven" (I: 248).

The Venetian island (or islands) of Murano today. Left: A general view. There are still large glass workshops in this picturesque place, which attract many tourists. Right: A furnace inside one of them.

In this way, and despite some later criticisms of the Salviati company itself — for replacing uneven paving in the left aisle of St Mark's with brand-new tesserae, for example (Cook II: 305) — Ruskin undoubtedly helped to prepare the way for Salviati's success in England. In fact it opened the way for the whole Byzantine Revival that produced so many glittering chancels in British churches during the late Victorian period. As for Burne-Jones, his own mosaic designs for St Paul's Within the Walls in Rome would later be executed at Salviati's workshop in Murano: the "Compagnia di Venezia-Murano."

Salviati in Britain: Mosaics

Left: A bit of Venice in the heart of London — close-up of part of the old Salviati mosaic, showing the lion symbol of St Mark flanked by ribbons bearing the names of two pre-eminent Venetian Dodges ("Dandolo" for Giovanni Dandolo, and "Loredano" for Leonardo Loredano), on the faaçade of 235 Regent Street, W1. Right: The monument over the grave of Salviati's son Guilo in Brookwood Cemetery.

By 1867 the firm was already very well known in England: it had premises on Oxford Street, and Salviati mosaics had been installed in "more than fifty Catholic and Protestant Churches in England including on the altars, the walls, the choirs, the pavements, and the baptismal fonts" (Barr 28). Showrooms were opened at various times and at various addresses in other fashionable parts of London (St James's Street, Piccadilly; Regent Street; and, for a while after the turn of the century, New Bond Street). Perhaps the most impressive showroom was that of Salviati, Jesurum & Co., which Rita Kovach explains was "a co-operative venture representing the Murano companies of Salviati & C., Jesurum & C., Venice Art Co, and Pagliarin & Franco." This was prominently situated at 235 Regent Street, which was newly built in 1898 and must have looked very splendid at the time. The mosaics above the windows here have been preserved, and so, like those of the Palazzo Salviati on the Grand Canal in Venice, can still be seen today. The names of the great cities of the world, ranged above the spandrels, suggest its world-wide operations.

It was not all plain sailing. In 1859, not so long after Ruskin drew attention to the wonders of Venice, and the very year in which Salviati founded his company, The Builder was pointing out that mosaic glass could be obtained from Murano if "our own manufacturers do not surpass or equal it" (qtd. in Sladen 81). This sounds like a challenge. At any rate, it was taken as such, and soon there were home-grown supplies, particularly from James Powell & Sons at their Whitefriars works. There were some problems too with Salviati's English investors, causing him to withdraw from the Venice and Murano Glass and Mosaic Company in 1877, and found separate glassworks operating under two names: "Salviati & C." for mosaic glass, and "Salviati dott. Antonio" for tableware and other glass items. On top of such complications, there was personal tragedy for the Salviati family: the very year (1898) that the big Regent Street store was opened, Salviati's middle-aged son Guilio shot himself at his desk, apparently due to "temporary insanity" ("Inquests"). He left a suicide note claiming that he had no money left and was in despair, although apparently the lack of funds was an utter delusion. Guilio's beautifully decorated headstone can be found in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey.

Still, right from the 1850s onwards, the firm's mosaics were commissioned for such important places as the Queen's Robing Room and the Central Lobby in the Houses of Parliament; the nearby Buxton Memorial; both Westminster Abbey and Westminster Cathedral; St Paul's; the Royal Albert Hall; the South Kensington Museum (i.e. the Victoria and Albert Museum), and so on. Of course, there were major commissions from outside London too, for example, for the huge mosaic over the entrance to Yeoville Thomason's grand Council House, Birmingham. Salviati executed many of the finest mosaics designed by the British architects and artists of the time, including the mosaics on the Albert Memorial for the firm of Clayton and Bell, and the mosaic replacing G. F. Watt's mural on the chancel arch of St James the Less, Westminster. Then there were all those other mosaics in humbler parish churches like St Mary's, Sunbury, one of the first to instal them. In such locations, these scintillating artworks can still be enjoyed now.

Salviati in Britain: Tableware

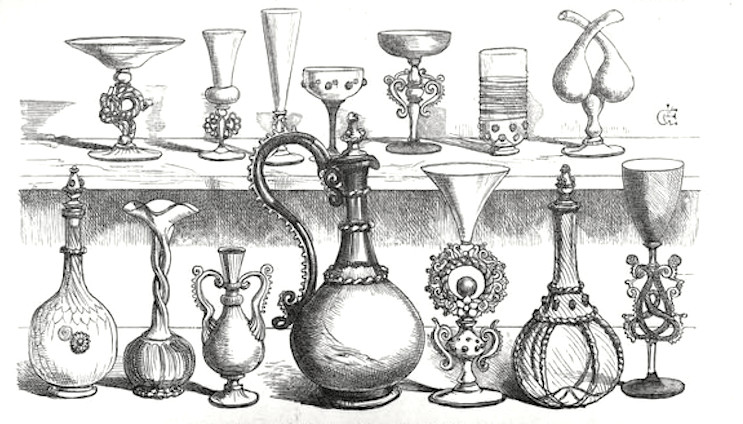

"Glass manufactured by Salviati & Co., Plate XXXVI, Eastlake, facing p. 227.

Yet, as indicated by the formation of twin companies in Venice, mosaics were not the only prized products of the Salviati enterprise. While Eastlake applauded "the revival of so venerable and splendid an art," saying that Salviati's mosaic work was "well appreciated" in England (226), he pointed out that Salviati did more to revitalise the glass-blowing industry of Murano. The firm's reputation also rested on its "holloware" or household and decorative glassware, in the early days considerably helped by Salviati's British friends and associates, particularly the well-known archaeologist and art historian Austen Henry Layard, and the antiquarian Sir William Drake. Among the architectural community, Richard Norman Shaw provided old examples of glassware for the artisans in Murano to copy.

At this point in his discussion, Eastlake takes us back to Venice, by paying due tribute to the artisans themselves:

In England, the great difficulty of bringing about such a revival would probably be the want of skill in the art-workman. But at Murano these poor glass-blowers appear to inherit as a kind of birthright the technical skill in a trade which made their forefathers famous. Better wages, a more interesting occupation than they formerly enjoyed, and, may be, a feeling of national pride which recent events [i.e., the incorporation of Venice into the new kingdom of Italy] have awakened, combine to encourage their efforts. [226]

The result of all this, at the time, was an influx of Murano glassware. Eastlake reports that a new depot has been opened for the firm's imports in St James's Street, and goes on to describe, in some detail and with keen appreciation, such items as those show above. Perhaps he would not have been surprised to learn that the name of Salviati continues to command respect today, not only in Venice, Britain, but all around the world.

Bibliography

Barr, Sheldon. Venetian Glass, 1860-1917. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 2008.

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. Vol. I: 1833-1867. London: Macmillan, 1904. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 13 March 2016.

Carboni, Stefano, and David Whitehouse. Glass of the Sultans. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corning Museum of Glass, Benaki Museum Athens (Exhibition Catalogue). New York and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

"Cathedral Mosaics Part II — Opus Sectile and the Italian Method." Westminster Cathedral. Web. 13 March 2016.

Cook, E.T. The Life of John Ruskin. Vol. II. London: George Allen, 1911. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University. Web. 12 March 2016.

Eastlake, Charles Locke. Hints on household taste in furniture, upholstery, and other details. London: Longmans, Green, 1869. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 13 March 2016.

"Inquests." Times. 9 March 1898: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 13 March 2016.

Kovach, Rita (of The Salviati Architectural Mosaic Database). Correspondence with the author.

Ruskin, John. The Stones of Venice. 2nd ed. Vol. II. London: Smith, Elder, 1867. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University. Web. 13 March 2016.

The Salviati Architectural Mosaic Database. Web. 13 March 2016.

Sanford, John. "Venetian Glass...." Stanford News Service. Web. 13 March 2016.

Sawyer, Paul L. The Plan: History of Typology (Ch. 5 of Sawyer's Ruskin's Poetic Argument: The Design of the Major Works, Cornell University Press, 1985. Whole text in the Victorian Web; this chapter here.

Sladen, Teresa. "Byzantium in the Chancel: Surface Decoration and the Church Interior." In Churches 1870-1914, the Victorian Society's journal, Studies in Victorian Architecture & Design. Vol. III. 2011. 81-99.

Extra pictures and text added 13 and 20 March 2016