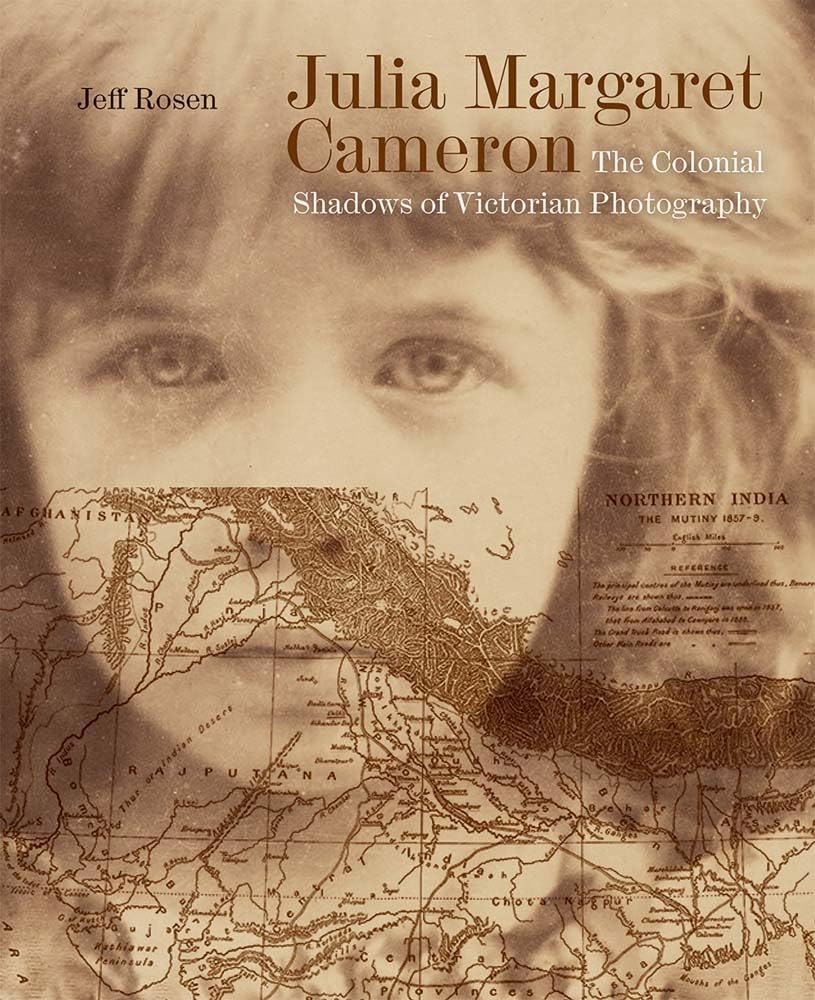

This is a fascinating, informative and thought-provoking consideration of (some of) the work of the Victorian photographer Julia Cameron by an author who has already made a valuable contribution to this field, in his 2016 publication Julia Margaret Cameron's "fancy subjects" (Manchester University Press). Indeed, were it not now so much a term of popular-cultural language, one might say this is a sequel to that earlier book. Beginning by appraising the ways in which Cameron has been cemented as a figure of consequence in the history of Victorian culture, Rosen seeks to supply one conspicuous lack therein, namely the neglect of "how an artist's photographs intersected with historical and cultural conflicts, especially the colliding global forces of colonialism, political history, and nationalism that transfixed Britain in the mid nineteenth century" (2). For his part, then, Rosen approaches the well-known photographer's output as "narrative history writing" and examines her and her art-work as essentially produced by the British engagement with India. Contending that Cameron "laid claim to the strategic role of allegory in constructing a historical narrative" (21), after giving up on realism, Rosen's thesis is that she thus "constructed the public face of British imperialism," concluding that the work under consideration amounts to "an imperialist polemic that could only have taken shape in the wake of the uprising in India" (233).

Section headings indicate this direction of travel: Outposts of Empire; Cross-Cultural Encounters; Allegories of Empire. Rosen reminds the reader that, although the starting date of Cameron's creative venture is tediously familiar (1864, "my first success"), she became interested in this new picture-making medium in the 1850s, as it developed most obviously as a means of portraiture and an aid to sightseeing. In explaining various subjects and their treatment in her hands, he makes use of literature, political history and social history, sometimes at wearying length, but in order to embed Cameron's photographs in a dense context in which current affairs and the state of society have more significance than ideas about art. As the book proceeds, alongside figures from politics, literature and Cameron's social life, he does bring in several other image-makers of the time (Rejlander, Millais, Watts, Marochetti) to press home his points – not all persuasive, it must be said – that serve to show that, on the one hand, artists are always acting in the light of their colleagues' activities but that, on the other, Cameron belonged to a remarkably self-referential social community.

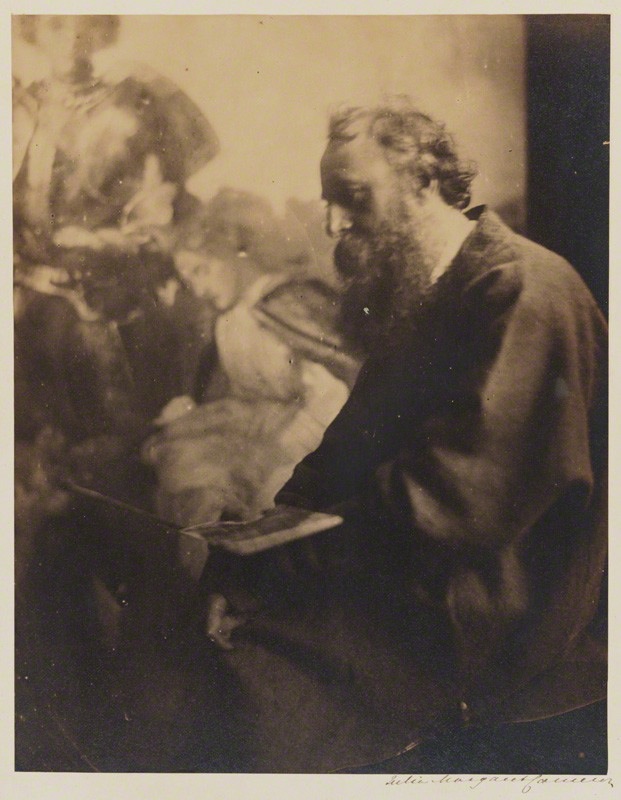

Cameron's portrait of G. F. Watts, working on his painting, The Red Cross Knight and Una, with its patriotic theme.

For the most part, this is very interesting, even though it does produce longeurs that will try the reader's concentration. Rosen shows that it is hugely relevant that Cameron's family, the Pattles, was formed by its time in India, with many individual members of the extended family connected for their entire lives with the East India Company and, by extension, the imperial sectors of the British government and its self-described "civilising mission." This applies to more than one of the Pattles' husbands also, and even though Cameron and her sisters are often characterised as self-determining, a woman's husband was typically still the most influential element in her life at this time, after her father. Details such as Cameron's fourth child (born 1846) being named for India's governor-general, and her brother-in-law Thoby Prinsep's authorship of The India Question in 1853, as well as her sister Sophia's marked mixed-race appearance, accumulate to a vividly concentrated image of this photographer as a layered individual occupying and active in a very particular time and place. It can often be forgotten that some of the key people in the story of Cameron's artistic journey, such as John Herschel, were also children of empire. Rosen shows us that even while the people from prime Victorian cultural history with whom we have become used to associate Cameron – Carlyle, Tennyson, Watts, Thackeray – were living in England, they must often have been thinking about India.

Cameron has by now been so widely studied that one looks in a new book on her work for fresh light on her photographs and her place in Victorian photography. Rosen's insistence on the impact and reverberations of the then-called Indian Mutiny of 1857 (for which he prefers the term "the uprising") amongst "old India hands" produces compelling insights into Cameron's mission and achievement as a photographer. The images she made of the men she is well known for glorifying - Herschel, her husband Charles, her brother-in-law Thoby Prinsep, her favourite man-of-letters Henry Taylor and even William Holman Hunt - take on new meaning in Rosen's account, while figures for which she has equally become known -such as Arthurian hero Galahad - acquire more resonance than they have been allowed heretofore.

Left: Cameron's photographic illustration of Sir Galahad and the Pale Nun, usefully discussed against the background of colonialism in India. Right: Déjatch Alámayou, King Theodore's Son, whose celebrity status at that time is belied by his forlorn expression in Cameron's carefully posed photograph.

Other images which have not been so well examined - such as King of Oude by right of birth (c. 1865) - also come under productive scrutiny. Rosen also proposes a new way of understanding some of her images of children, including her own, whom she often photographed, and her female servants (although these cases were far less convincingly argued, for this reader).

Highly focussed, then, though Rosen's investigation is, it takes a long and laborious route through its subject, and those readers turning to this book to learn more about mid-Victorian photography will be obliged to take in their stride obscure elements of Victorian drama (what price the plays of Tom Taylor?) and literature (Thackeray turns his hand to poetry) as well as the lengthy detail of British governance in India and the biographies of minor members of Cameron's family and social circle. There is surely much more political history here than necessary to make the author's point, even given his aim, while the narrative in some places - the length of detail given about British media coverage of the atrocities of the Mutiny/uprising and then the Cawnpore memorial - rambles away from the main object of investigation, Cameron's photographs. There is, too, occurring throughout a tendency to contrivance or speculation, some over-thinking, one might say, (e.g. 97-107, 175-181) that undermines Rosen's basically sound scholarship and valuable interpretation.

A valuable book, then, which holds interest for anyone who has followed Cameron's rise to prominence in the modern era's roll-call of Victorian image-makers since Alfred Stieglitz trumpeted her merit in 1913; but which those interested in both the general question of the intersection of British politics and culture and the specific issue of India in the Victorian consciousness will also enjoy.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

(Book under review) Rosen, Jeff. Julia Margaret Cameron. The Colonial Shadows of Victorian Photography. . London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2024. pp.282. £45.00. ISBN 978-1-913107-42-0

Created 10 September 2024