Who would have guessed that at the heart of emerging mass culture in nineteenth-century America was a bald orphan named Mickey Dugan? According to Christina Meyer, Mickey Dugan, or The Yellow Kid, was one of the most influential figures in producing a mass phenomenon of serial production and consumption in 1890s New York newspaper comics. Meyer’s project seems simple at first glance: to trace the wild case of The Yellow Kid, “one of the first mass-produced and mass-consumed commercial cultural artifacts” (3), and to understand what made him so special, so famous, and so widely disseminated — until his demise in 1898. However, she actually takes on a much bigger responsibility of historically and formally accounting for the multiple ways in which the figure of the Yellow Kid was taken on beyond the newspaper comic, and how he became a “transformable, portable, versatile figure” (13) who not only reflected and reified his New York surroundings in his comics, but even shaped them — by becoming so much a part of them, with his endless reproductions and proliferations.

Producing Mass Entertainment is organized into four chapters and a conclusion. The first chapter, “Diffusions, or, How Did the Yellow Kid Go Serial?” follows the rise and origin of the Yellow Kid’s figure, but also brings in secondary productions — drawings, letters — by the readers of the Yellow Kid comics, once the character became a staple. The second chapter, “Serial Aesthetics and Consumption Practices of the Yellow Kid Comic-Tableaux” is a collection of the Yellow Kid’s various formats, media, versions that put into question the place of authorship over such a figure. This discussion retroactively fuels the pieces of secondary creative efforts by the readers already outlined in Chapter 1. It also begins to read the unique aesthetics of serial form, such as the repetitive markings or props in the comic that flag certain characters, which then gain their own narrative life to repeat themselves with difference every time they reappear, and the liminal status of the Yellow Kid (not only an Irish immigrant orphan in the alleys, speaking in vernacular, but also literally existing in the margins of the paper) allowing his appropriation and infiltration into multiple scenes and places. The third chapter, “Branching Areas of Interest in the Comic-Tableaux,” reads the motif and concept of a "copy" in the comics, which was a site of both pleasure and anxiety as the Yellow Kid became so copied and reproduced not only in the “cheap and fast mass-productions,” but also in pirated, faked, or unauthorized imitations (120). This was complicated by the fact that, as Meyer will recount in painstaking detail, the Yellow Kid comics were published in competing newspapers — Hearst’s American Humorist and Pulitzer’s Comic Weekly among others — to question and affirm a wide range of messages and insinuations about class and racial hierarchies. These competing energies within and without the comics, Meyer argues, catered to different readership and modes of reading. The fourth chapter, “Spawning Continuation?” addresses Richard Outcault and Edward Townsend’s sequel to McFadden’s Row titled Around the World with the Yellow Kid, a more continuity-based series of the Yellow Kid, which has been critically overlooked in previous studies of the character. Her study of this comic yields also a fraught site in which parody and earnest political messages are mixed, and the authorial ownership over the character and the series are constantly established and challenged. Meyer convincingly reads this paradoxical yet complementary form of the Yellow Kid comics through the wildly inconsistent narrator, haphazard temporal shifts, and most importantly two separated forms of the comic — one, the “weekday business-travel leaflets” that illustrated an account of the travel in — rather conservative — political terms, and the other, the “Sunday leisure-travel comic-tableaux” that parodied the Grand Tour in more humorous, biting ways (176).

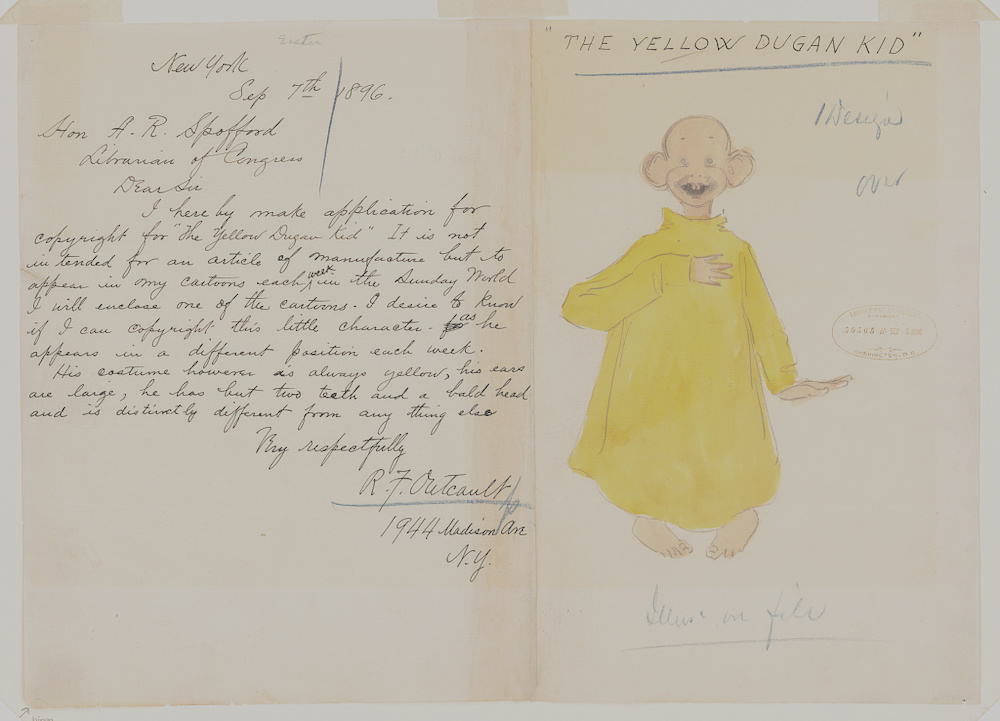

Outcault's copyright registration drawing of the Yellow Dugan Kid, submitted 7 September 1896 before he switched from the New York World to the New York Journal. Library of Congress image, Reproduction Number LC-DIG-ppmsc-00180. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Meyer’s methodology is, as already hinted, while historically laser-focused, surprisingly formalist — she makes it explicit that her “investigations to follow do not attempt to trace actual reading experiences and interpretations of the comic-tableaux” (10). Rather, she aims to point out the capaciousness of reader options, through her readings of “the pictorial parts, including color and typography, as well as in and through the words in speech balloons, captions, and narrative columns” (10). Her aim in not only meticulously covering the various forms and appearances of the Yellow Kid across different publications, over different serial schedules, but also reading how each of these appearances were formally accommodating multiple reader needs, is to trace the sheer plurality of the Yellow Kid’s representation and mode of consumption. She further argues that this abundant experience of reading the Yellow Kid was distinct from what the “products of other cultural fields of modernity such as, for instance, documentary photography, literature, or art, did not provide,” because each episode of the Yellow Kid “in itself offered multiple readings and could be enjoyed without knowledge of a previous or future installment” (11).

The main thrust of Meyer’s argument, that the Yellow Kid cultivated a mode of reading that heightened the multiple possibilities of message, authorship, and even just formal order in the reading experience of comics, brings a fresh outlook on the critical discussion around how comics afford certain kinds of reading. Classic studies in the field have covered the ways in which comics, through manipulations of text and image, cater for a certain temporal experience of reading — Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, or Thierry Groensteen’s The System of Comics both advocate for the power that the melding of image and text in comics has in shaping the tempo and duration of reading. However, what Meyer is offering is the opposite — rather than arguing for how the comics' form holds power in shaping a certain reading, Meyer’s reading of the Yellow Kid comics — one of the first of its kind in cultural consciousness — asserts that the power of comics form lies in the infinite possible order and meaning that it can present to the reader. Where others saw innovative control of reading experience, Meyer sees an explosion of such control in the very nature of Yellow Kid’s character. In a certain sense, Meyer’s reading of the Yellow Kid comics seems to foreshadow the more recent experimental comics that have been hugely successful by capitalizing on specifically this aspect of reading comics, such as Building Stories by Chris Ware, which consisted of various medial forms of "comics" in a box, allowing the readers to interact with disparate pieces of narrative in whatever order they chose. These kinds of connections are not made by Meyer herself, though she seems to also press on this point, even through the form of her own argument: she claims, at the end of her introduction, that “the different parts in this study do not have to be read consecutively. Each of the chapters ... can be read without the knowledge of the preceding or the following one” (18).

However, I would ask a question about this formalist reading of a profoundly historical object: why not address some systemic contexts in which these proliferations of the Yellow Kid took place? In other words, what can these readings of the pages that surrounded the Yellow Kid signify in the larger cultural and historical context that persists to modern age? What did it mean that the Yellow Kid was able to proliferate to such an extent? She begins to answer this question in the conclusion, where she points out that the critical rhetoric that surrounded the Yellow Kid represented it as a “harmful and inappropriate… ‘low’ cultural product” (186). Meyer asserts that, unlike the previous off-hand explanation that the Yellow Kid’s symbolism as yellow journalism was why it was so denounced, “the Yellow Kid was cast with a critical eye first and foremost because the comic figure proliferated so rapidly and extensively (like a plague) and because it leaked into all kinds of spheres and fields of private and public life” (186). This argument, that the metaphor of disease ran through the negative rhetoric against the Yellow Kid, is a salient and productive point. It could have been built up to a more enduring systemic critique of capitalism and its relationship to burgeoning mass culture, but Meyer stops just short of doing so, stating briefly that the Yellow Kid’s “operations of repetition, multiplication, and spread,… were embedded in and spawned by the economic structures, technologies, and ideologies of capitalist culture,” without naming those ideologies (188). This also brings up the question of what Meyer thinks of "form," a charged keyword in a discussion regarding experiences of reading and narrative theory. After powerful and delightful readings of the Yellow Kid’s career in the newspapers and beyond, Meyer’s conclusion leaves the reader wanting when it comes to asserting the project’s influence on the present state and form of comics. She cites various winks to the Yellow Kid in modern media — even a cameo in the NBC sitcom Frasier — but leaves the reader to imagine how her formulation of “serial aesthetics,” so robustly read in the Yellow Kid comics, can be transported, like the figure of the Yellow Kid, into thinking about the form of comics today.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Meyer, Christina. Producing Mass Entertainment: The Serial Life of the Yellow Kid. Columbos, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2019. 278 pp. Pbk. $34.95

Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press, 2009.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

Ware, Chris. Building Stories. New York: Pantheon Graphic Library, 2012.

Created 19 March 2021