The following report has been transcribed and formatted, along with its scanned illustrations, by Jacqueline Banerjee. It is of great interest because it details the foundation of one of the first two teacher-training colleges in the country (the other was St John's College, Battersea, founded by Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth and E. Carleton-Tufnell in 1839-40). St Mark's represented the fulfilment of the vision of another pioneering educationist, Derwent Coleridge, son of the poet Samuel Coleridge. Click here to find out more about the buildings themselves. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The gratifying debate which has this week taken place upon the all-important subject of National Education induces us to lay before our readers engravings and an account of one of those institutions which have been already established for the purposes of public instruction — or rather for the normal instruction of those upon whom the education of children will afterwards devolve. The college in question was founded by the National Society, which, however, did not extend its exertions to the general scheme which Government has announced its intention to propose, but confined its influence exclusively within the pale of the Protestant Established Church.

This society has for some time considered that the unfitness of schoolmasters for their work of teaching has long operated to the prejudice of those to be taught. This duty is commonly performed "for less than labourers’ wages, without present estimation or hope of preferment, by the first rustic, broken-down tradesman, or artisan out of employment, whom necessity, or perhaps indolence, brings to the employment." The majority of those who seek to be school-masters are all but uneducated men from the working classes. "Almost uninstructed, and utterly untrained, with little general fitness for their calling, and no special apprenticeship, they may teach a little, and this not well, but they cannot educate at all." They may be taught a system, but they want the first condition of teachers — the application of the particular method. The best preparation which such a man can receive — short of a complete course of training — is superficial and formal. He must himself be educated before he can educate others.

The National Society, feeling the necessity of this "normal education," and the eonsequent providing of a superior description of schoolmasters, in order to meet this want, have established training-colleges, one of which is shown in the engraving. It is situated at Stanley Grove, at the western extremity of the parish of Chelsea, being divided from the parish of Fulham by the Kensington Canal. It lies between the King’s-road and the Fulham-road, by either of which it may be approached; by the former it is about three miles from Westminster Abbey, and by the latter about two miles and a half from Hyde Park Corner. It contains about eleven acres of ground, principally freehold, already beautifully and usefully laid out by the late proprietor. The excellent mansion-house with its adjoining offices have been found of easy adaptation to the purposes of a training-college, and to these has been added an extensive range of dormitories. The college, as now complete, consists externally of a centre and a handsome wing, added by the late proprietor, and a quadrangle erected by the society from the designs of Mr. Blore, in one of the Italian styles.

The front entrance is by a vestibule, communicating directly both with the apartments of the Principal and with every part of the public establishment. The principal apartments are a committee-room, spacious and lofty lecture-room, and class-room, and dining-hall. There are forty-four small sleeping-rooms disposed along three sides of a corridor, connected at each end with the main house. At the two outer angles are towers or pavilions, each containing a sitting-room, master’s bed-room, and three smaller chambers for boys, thus affording accommodation for fifty students and two masters, with a separate apartment for each. The offices need not be described. Part of a separate building has been fitted up as an infirmary, and a small farm-yard with outbuildings has been put in order for the institution. The several college buildings, with the chapel to be presently described, occupy about one third of the ground; there are two kitchen-gardens and three small meadows, and the whole is surrounded by a wall. "It is perfectly healthy, being on gravel, with an abundant supply of good water, while the fine trees, to which the place owes its name (Stanley Grove), give it an aspect not inappropriate to its present destination. To have secured such advantages in the immediate neighbourhood of London may, indeed, be regarded as most fortunate."

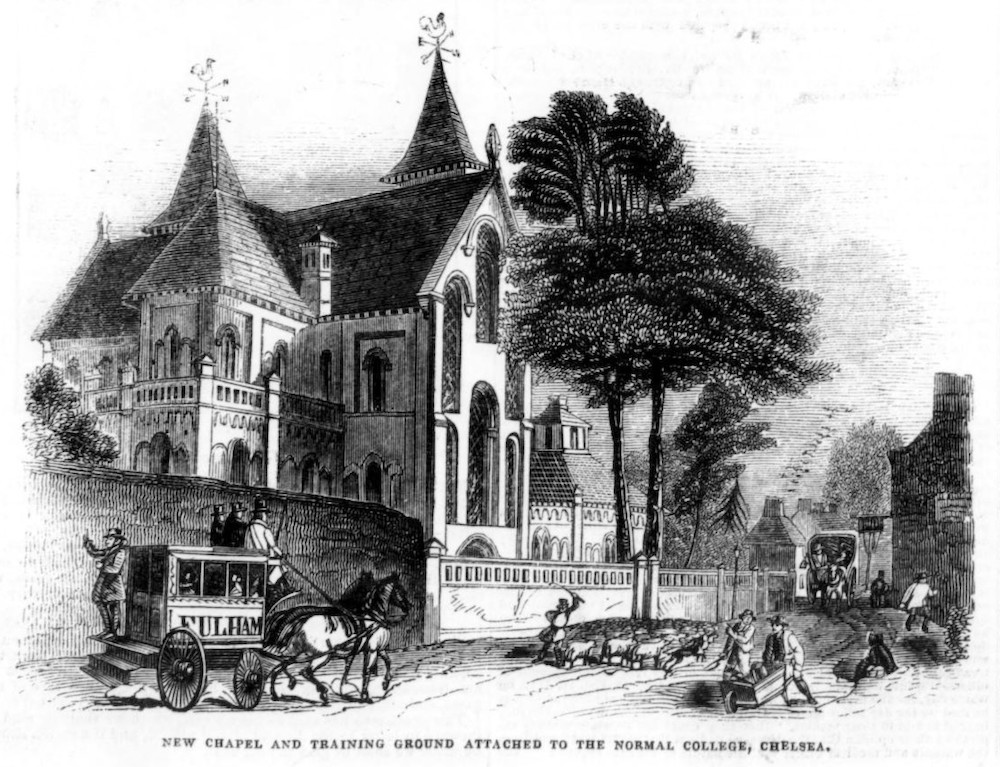

New chapel and training ground attached to the Normal College, Chelsea.

The chapel, shown in the annexed engraving, faces the Fulham-road, as the college itself does the King’s-road. The former is cruciform in plan, with a semicircular eastern end. The principal entrance is at the western end, which, with the transept-like wings, have lofty gables. In the former is a large circular or rose window. The entire building is well lit by circular-headed windows, partaking of the Anglo-Norman style. From the west side of each transept, at its junction with the choir, rises a campanile, or bell-tower; the material is fine light brick, and the effect of the whole composition is pleasing and picturesque. It serves as a place of worship for the adjoining district, as weil as for the inmates of the college. The society is glad to combine in this way a considerable local benefit with its own objects; but no sacrifice has been made, nor any extra expense incurred, for this purpose. A small domestic chapel might have served; but the students would not then have been habituated to the solemnities of public worship, and it is desirable that there should be a general congregation.

At a short distance westward of the chapel is a practising-school for 130 scholars from the neighbourhood, who are taught by six pupils and a master from the college. The school fee is 4d. per week, but there are free scholars. The building is of octagonal form, and its arrangements are very novel.

The college is intended to consist of 60 students, superintended by a Principal and Vice-Principal, who will divide with him the duties of the chapel, and two resident teachers. The Principal is the Rev. Derwent Coleridge, who has drawn up an excellent account of the college. All the students are to be apprenticed to the National Society until each shall be twenty-one years of age. One of the teachers directs the labours of the apprentices out of doors, is steward, and manages the farm and garden. A master has been appointed for the practising-school. Vocal music and drawing are taught by masters, and a drill-sergeant gives lessons in gymnastics. Boys are admitted at from 14 to 17 years of age. Hence the college is not a preparatory-school, but approaches more nearly to an university, from which, however, it differs in all the students being destined for one particular calling. "Three months’ probation is allowed for each candidate, and his fitness is determined before the indentures are signed. A premium to cover personal expenses (£25 per annum) is expected, but this may hereafter be dispensed with. At the opening of the college, ten free apprenticeships were offered by the committee for public competition, and quickly and satisfactorily filled up. We have not space to describe the youth to be selected for the college further than that he should possess a certain seriousness of character, which appears at a very early age, and insures earnestness, reflection, and good sense. He must read with intelligence, and write correctly from dictation. A very simple education, with a ground-work of religious knowledge, will suffice. Good health is indispensable. A strong, well-grown boy is preferred; and simple manners, and pleasing address, however rustic, are desirable. Faulty pronunciation, and coarse accent, are objectionable; for every schoolmaster should speak his own language with perfect propriety. Latin is taught, though only as far as a sound acquaintance with the accidence, syntax, and etymology of the language, for the sake of the English language, although English grammar is distinctly studied. The intelligent reading of the Scriptures is carefully enjoined. Geography, the principles of numbers, algebra, and trigonometry are taught. Of physical science, botany is preferred. Geometrical perspective is not neglected. Mr. Hullah gives lessons in vocal music, in connexion with the daily service of the chapel. The cost of maintaining each student is but 5s. 2d. per week. The clothing comprises a Sunday and working suit: the former is made of black or dark cloth, with shoes and gaiters, and consists of a frock-coat, or a round jacket, waistcoat, and trousers, a black silk hat, and white cravat: the latter is a round velveteen jacket and waistcoat, with fustian trousers and heavy shoes, a brown holland blouse and a straw hat for summer. The whole outfit, with linen, and a cotton umbrella, and a pair of strong leather slippers (to be worn in the house), costs seven guineas. The industrial system has been devised as well for balancing the intellectual pursuits of the students by manual labour as for economy: they perform the business of male servants in the house; milk the cows and manage the produce of the farm, and work in the gardens, lawns, and shrubberies; these duties being assigned to different parties weekly. It should, however, be observed that the service of the chapel is, as it were, the keystone of the entire system of the college.

The National Society have already raised the sum of £30,000, of which £20,000 has been appropriated to the foundation of this training-college; the purchase-money of the mansion and grounds being upwards of £9000. The annual expenditure, when the college is full, will be about £3000, of which two thirds will fall upon the income of the society. The entire cost of educating each schoolmaster is estimated at from £150 to £200 — a small sum in comparison with the permanent benefits which this system must insure to society.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

"Training-College for Schoolmasters." Illustrated London News No. 44, Vol. II (4 March 1843): 158. Internet Archive. Web. 12 June 2024.

Created 14 June 2024