Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

The decorative headpiece above, decorative letter T, and the clockface tailpiece all come from the original article, as do all of Harry Furnis’s illustrations. The original article appears in double columns with some of the illustrations spread across the full page, and I have placed them in that position. In transcribing the following article I have followed the invaluable text off the Hathi Trust online version. Furniss’s illuminated T begins the original article. — George P. Landow .

HERE is a difficulty in speaking of the Post-Office without recurring at once to that ideal Postmaster-General who, but a short time since, was struck down in the discharge of his duties. Until comparatively recent years, the Post-Office has owed its popularity chiefly to reforms and im provements forced upon it from without. This was the case with the Penny Post, and with most of the earlier improvements in the mail service. The late Mr. Scudamore seems to have been the first official possessing at once the popular instinct and the power of organisation, and while he was the ruling spirit at the Post-Office the Savings Bank and the Telegraphs were added to its labours.

Mr. Scudamore was deposed; and the Post Office ceased to do more than furnish an occasional paragraph to the papers, till Mr. Fawcett took office. Mr. Fawcett at once realised the value for social purposes of the machinery which moved at his bidding. He set himself to consider in what directions it was best fitted to do useful work, and at the same time he lost no opportunity of improving the good understanding between his Department and the public. While resolutely setting his face against the tendency to snub, which is a besetting sin of oflicialism, he lost no opportunity of dwelling in public upon the services of the Department and the anxiety which exists amongst good officials to do thoroughly well the work allotted to them. Inside the Post Office he took care to let it be known that he personally valued the labours of the humblest letter-carrier, and thoroughly appreciated the zeal and energy shown by the working staff throughout the country. In his first year of office he succeeded in carrying through Parliament two most popular measures — the Act for enabling savings bank depositors to invest in Government stock and that inaugurating Postal Orders. At the same time he introduced another aid to thrift, the use of stamp slips for savings bank deposits, by means of which the minimum deposit was reduced from ls. told. And he set on foot an inquiry into the comparative failure of the inducements offered by the Government for the purchase of annuities and insurances, and got rid of many formalities which tended to make the system unpopular.

But the social reform with which Mr. Fawcett’s name will be most prominently associated is the Parcel Post. The idea of carrying parcels by post is well nigh as old as the post itself. Parcels were carried by the London Penny Post in the time of Charles II. A few years later the officers and messengers engaged on this service are found complaining that the Controller “forbids the taking in of any bandboxes (except very small) and all parcels above a pound, which when they were taken did bring in a considerable advantage to the office, they being now at great charge sent by porters into the city, and coaches and watermen into the country, formerly went by Penny Post messengers, much cheaper and more satisfactory.” About the same time, during the war with France, very curious parcels were entrusted to the Post-Office for conveyance to the Continent; “Fifteen couples of bounds going to the King of the Romans with a free pass.” “Two servant~maids going as laundresses to my Lord Ambassador Methuen.” These must be taken, however, to be casual consignments, and no systematic parcel service sprang out of them. Sir Rowland Hill in his day looked forward to the carriage of parcels by post, but was deterred from the endeavour to realise his wishes by the difliculty (which has always been the lion in the path) of making fair terms with the railway companies. On the Continent, where this difiiculty does not exist, parcels have long been conveyed by post, and in 1880 an international parcel post was organised; but England was unable to avail herself of the benefit of the arrangement. Communications were opened with the great carrying agencies on the subject of a parcel post, but it was long before any terms could be arranged. At length the choice had to be made between an indefinite postponement of the post and an arrangement with the railway companies which would give them more than half the profit for much less than half the work. But Mr. Fawcett never hesitated where the benefit of the public was concerned. Much as he disliked paying more than was equitable to astute railway directors and managers, he would not let this feeling stand in the way of a great social improvement. The necessary concessions were therefore made, the Parcel Post Act passed through Parliament in the crowded session of 1882 without opposition, and the post had been in operation more than a year when its author was snatched away.

At the time of Mr. Fawcett’s death the first clear indications were coming to the surface that the Parcel Post would not fail in attaining that popularity which had been predicted for it. Anticipations were at first undoubtedly disappointed. In August, 1883, the first month, the Post Office carried a million and a half of parcels, or at the rate of nearly eighteen millions and a half in the year. The numbers increased rapidly in the three concluding months of the year, but fell again in the spring, and it was not till a complete year had passed, and it was possible to compare month with month, that that steady increase was discernible which is sure proof of popular favour. In October, 1884, the last month completed before Mr. Fawcett's death, the increase in the number of parcels over that carried in the preceding October was 18 per cent. Since that time the number has steadily risen, and the Post-Office now carries more than 33,000,000 parcels in the year—far above the number originally estimated. The average weight of parcels is still, however, much lower than was expected. The parcel rates, it will be remembered, are 3d. for 1 1b., and 1 ½r d. for every succeeding pound up to 11 lbs. It might have been thought that the average weight would be more than half the maximum, but on the contrary, it has invariably since the commencement of the post been below 3 lbs., and still shows no tendency to increase. This, it will be seen, brings the average postage to less than 6d., and when it is added that the great bulk of the parcels carried (more than nine-tenths) travel by rail, and that in every such case the railway companies take 55 per cent. of the postage, it is obvious that the Post Office is not over-paid for the work it does.

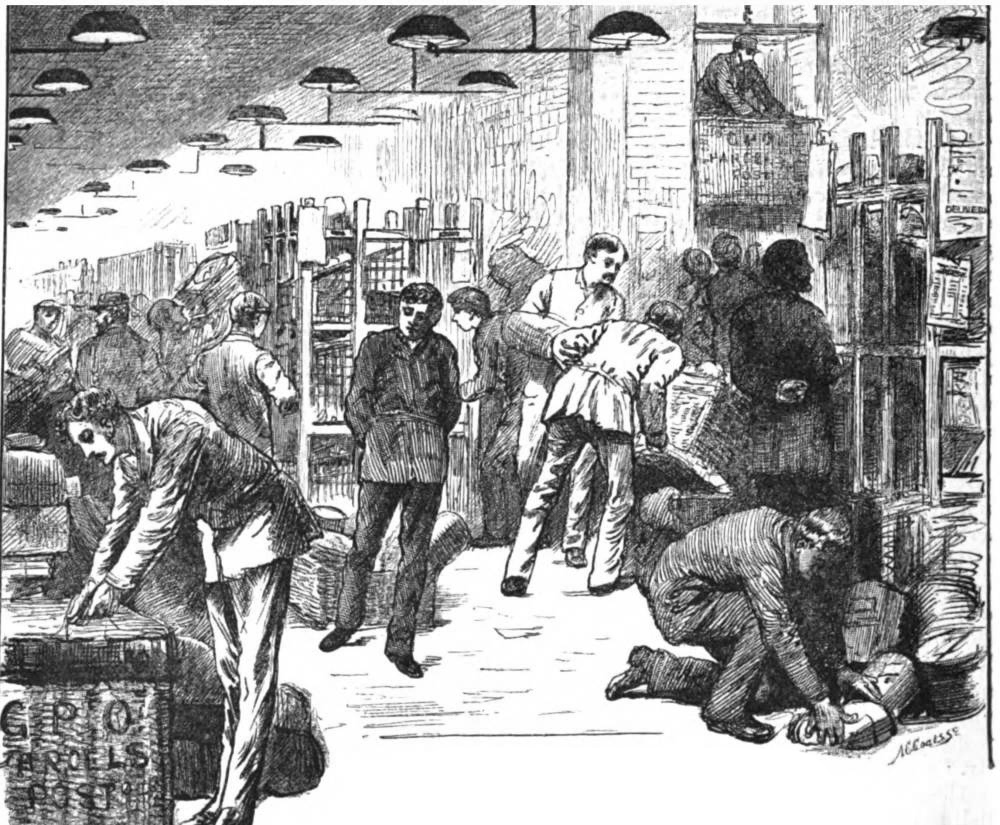

For a parcel cannot be handled in the same summary way or in the same space as a letter, and economy of time and room is of the essence of cheap mail-work. To begin with, a parcel cannot, like a letter, be posted in a box. It must be taken to the counter of a post-office, where its weight, size, and stamps can be checked. For this purpose, at the General Post-Office, a separate room with a long counter, on the ground floor of the old building, is provided. From this room the parcel is transferred by means of a shoot to the sorting and despatching room, a large airy department, which has been obtained partly by developing the basement of the building and partly by excavating under the yard. Lined with glazed white bricks and lighted by windows high up in the walls, this underground workshop has anything but a gloomy appearance; and in it is transacted the busy scene sketched on the opposite page. As soon as the parcels reach the room they are sorted into baskets, varying in depth from about a foot at one end to eighteen inches at the other, and constructed to fit into a kind of crate or framework which stands in the middle of the room and can be approached from each side. These sorting-baskets are labelled for various districts in London and for the depots which have been formed in the neighbourhood of the great railway stations. When they are full, they are taken from the framework, and drawn to the great posting-baskets which are to convey the parcels on their next stage, and the out ward appearance of which has become very familiar by this time to all travellers by rail. In these the parcels are packed, a second loose lid being used when the basket is not full, to keep its contents in place. When packed and secured the baskets are wheeled off to the hydraulic lift, by which they are raised to the world above, where they take their place in the proper waggon and com mence their journey.

Although it is impossible to handle parcels with the same rapidity as letters, practice is enabling the sorters and packers to make quick work of the continual emptying and refilling of baskets, and at a busy time there is plenty of activity and bustle in the parcel-rooms.

Parcel Sorting Room by Harry Furniss. Click on images to enlarge them

At Christmas a severe strain is put upon the force. At many ofliccs the number of parcels is double that dealt with in an ordinary week. The increase begins about the 22nd, when well-regulated people who are always in time send off their Christmas presents, and tradesmen begin to execute their country orders. On the following day there are perhaps fifty per cent. more; and on the 24th the rush culminates, and nearly as much work is done as in the other two days together. One of the great depots, such as that at the London and North Vv’estern Station, is worth a visit on such an occasion. Every kind of article from an umbrella to a bottle of whiskey is to be found, and of course there is a certain proportion of badly packed parcels. Sometimes the care lessness goes so far as to lead to the loss of the address and then some one may perhaps be disappointed of his Christmas dinner. No less than 74,000 parcels could not be delivered during the last post-ofiice year owing to insecure packing and incomplete addresses. Indeed upon the very first day of the Parcel Post a notable instance of bad packing was afforded. A number of leeches escaped from the bottle in which they were travelling, and were found strolling over the floor of the General Post-Office. And last Christmas at Euston a fine hare and a goose were both stranded owing to the loss of the scrap of pa per which was their only covering, and which alone afiorded any clue to their destination.

The Battery Room, General Post-Office by Harry Furniss.

The Parcel Post was unduly slow at starting. Parcels were a couple of days on a journey which occupied a letter half a day; and there can be no doubt that the Post Office suffered severely in competition with the railway companies in consequence. But this fault has now been mended. Parcels and letters generally travel together, and the only difference in treatment which afiects the public is that a parcel, like a book packet, may have to be posted half-an-hour sooner than a letter, or may be delivered an hour later. Mr. Shaw-Lefevre, when Postmaster-General, made the experiment of despatching a hundred pairs of parcels to places selected haphazard, one of each pair being sent by post and one by rail. In seventy one of the hundred cases the parcel was delivered sooner by post than by rail, the advantage in time being on the average more than five hours. Moreover the Post-Office in every case delivered its parcel at the address, while in many cases the railway company only took it to the nearest station, whence it had to be fetched by the recipient. In the great majority of cases, moreover, the postage was less than the charge by rail. With these advantages the Parcel Post will probably in the long run do what was originally predicted of it, absorb the greater part of the traffic in small parcels. In many respects, besides, I find the service has been much improved since it was first instituted. Not only has the maximum limit been raised and the scale of payment been made more favourable to the public; but the Postmaster General has given compensation to the amount of twenty shillings for the loss of a parcel or injury to its contents; and a parcel may be insured to the value of £10 for the trifling payment of 2/11. Moreover a Parcel Post has been established to all the principal European countries and to most of the Colonies. With the introduction of these improvements the service inaugurated by Mr. Fawcett may be considered to have passed from infancy to vigorous youth.

The Switch-Board Instrument Galleries, General Post Office by Harry Furniss.

But we must turn to that large addition to the work of the Post-Office which was madesome fifteen years ago under the auspices of Mr. Scudamore. The postal service is interesting on account of the extent of its organisation and the efficiency with which it works. The telegraph department is remarkable from the extraordinary nature of the force which it makes subservient to men’s convenience. What, for instance, is more marvellous that men living hundreds of miles apart, should be talking to each other, thanks to a certain chemical process which is taking place in absolute silence in a number of jars standing on shelves in the General Post Office? Yet this is nothing but a statement of the very elementary truth that electricity is produced by means of a galvanic battery. There are in the new Post-Office building three miles of gallipots containing the chemical agents by means of which all the telegraph wires which leave London are charged with electricity. Each pot is known as a cell, and a varying number of cells, sometimes four, sometimes eight or more, form a battery. From each battery two wires are conducted to an upright board, known as a switch board, where they are attached to a pair of brass knobs, each knob being numbered. Hence the wires are conducted to corresponding knobs on a similar board in the Instru ment Room at the top of the building and from this board they find their way to the instruments themselves and out of the building on their round of work, long or short as the case may be. The instrument galleries are not marked by the same dignified repose as the battery-room. On the contrary they produce that sense of excitement and bewilder ment which is associated in most minds with the machinery annexe of an exhibition. We have all heard the click-click of a telegraph instrument in a railway station or post ofiice. Imagine five miles of such instruments, and fourteen hundred telegraphists at work at once, and add to the musketry rattle thus produced a heavier artillery in the constant snap of the valves of pneumatic tubes, and some idea will be gained of the efiect on the hearing alone. Looking along the galleries we see rows of broad writing-tables at which men and women sit face to face separated by their instruments and generally by a glass screen, above which are shaded lamps and trays to hold telegraph forms. The vista is endless, for the galleries run round the four sides of the building and across its centre, light being admitted on the inner sides by means of small quadrangles, and the building covers very nearly an acre of ground. Lately an additional story has been added to the building, and over this also the telegraphists and their instruments have flowed. It is calculated that even this additional accommodation will shortly be exhausted; and the Post-Office has recently pulled down the Queen’s Hotel and the old Bull and Mouth Receiving House, in order to erect upon this site another huge pile of buildings.

Four Messages over the Same Wire. by Harry Furniss.

There are in all about 2100 telegraphists now employed in the General Post Office,of whom over 700 are women. They are not allowed to leave the building during their hours of duty, and extensive cloak rooms, kitchens, and refreshment-rooms have been provided for their use in a separate building on the other side of Bath Street, access being given by two bridges. A good telegraphist may earn as much as £190 a year, with the prospect of promotion to the post of superintendent, when he may rise to £350. When the long hours and constant attention required of a good operator are taken into account these wages certainly do not seem high. But, as Mr. Fawcett said in the House, the public cannot be generous and get a cheap article at the same time. To obtain cheap telegrams a fair market rate of wages must be adhered to, and that the present rates are fair is shown by the competition for the appointments.

Five out of every eight messages which are sent over the post-office wires pass through the instrument-room at the General Post Office, or in other words more than thirty millions of messages in the course of the year. At one time a larger proportion of messages were sent direct from place to place, but it was found that this system led to some wires being only half employed while others were overcrowded, and the tendency has for some years been entirely in the direction of centralisation in telegraph work. The busiest time for ordinary messages is from ten to one in the morning; for the Stock Exchange and the betting fraternity—the best patrons of the telegraphs—as well as commercial men generally, are busiest between these hours.

But after six in the evening the work takes another complexion. Press messages then begin to throng the wires. These messages are sent under Act of Parliament at a lower rate than ordinary messages. No more than one shilling for a hundred words is paid by the proprietor of a newspaper for the messages of his correspondents if, sent between six in the evening and nine in the morning; during the day the charge is a shilling for seventy-five words. Moreover a duplicate message can be sent to a second newspaper for an extra payment of only 2d. for every hundred or seventy-five words as the case may be. Some newspapers find that even these advantages are not sufficient for their purpose, and they hire the exclusive use of a wire between certain points during the evening and night; and over this wire any quantity of matter can be sent without payment beyond a fixed rental. Independently of the matter passing over these special Wires, the average number of words supplied to each newspaper has risen from 4,000 a day, when the telegraphs passed into the hands of the State, to about 20,000, while on a special occasion, such as the introduction of Mr. Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill, over a million words have been sent in a few hours. It may be imagined that the Post-Office does not profit by sending this great quantity of news at so low a rate, and were it not for the despatch with which the work is done, the loss would probably be greater still. We can all judge of the rapidity with which news is transmitted from the fact that we often read in our newspapers the reports of long speeches made at distant places within a few hours of their delivery. We realise better, however, what ingenuity and labour contribute to this result when we are told that messages can be sent and received over certain instruments at the rate of 450 words per minute.

It has taken many steps in invention and adaptation to achieve this result. In the first place nearly all telegraphic signalling is conducted by means of an artificial alphabet, in which each letter is represented by a com bination of two signals. In the single needle telegraphic instrument which is commonly seen in post-offices and railway stations, and of which the Post-Office has nearly 4,000 in its service, the two signals are deflections of the needle to the right and to the left respectively. One deflection to the right represents one letter, one to the left another, one right and one left a third, and so on. In constructing the alphabet the simplest symbol are not adopted for the first letters, but for those which are used most. The letters 0 and t are found to be those most frequently used, and e is therefore represented by a deflection to the left and t by one to the right. The letters next in demand are a, i, n, and m, and these are accordingly indicated each by two deflections of the needle, 1' by two to left, m by two to right, a by one left and one right, and in by one right and one left. Letters less constantly in use are indicated by combinations of three and four deflections. Thus a complete alphabet is formed, no letter of which requires more than four deflections to represent it. The deflections of the needle are produced, in the usual form of the instrument, by moving a handle to left and to right, and no special skill is required to work the instrument slowly, though, as may be imagined, long practice is required to attain rapidity in sending messages. The single-needle instru ment is the cheapest to make and the most economical to maintain, and it is consequently best adapted to places where there is not a great pressure of work and no great rapidity is necessary. The utmost speed that can be attained by it, however, is about thirty-five words per minute, and the average rate not more than twenty-five; it commonly sends about thirty average messages in the hour.

A much quicker instrument is that known as the Sounder, one of which will be recognised by its wooden hood in one of our artist’s pictures. In this instrument no visible signal is made, but the message is read from a succession of sounds. Each signal consists of two taps or ticks. Two taps in quick succes sion take the place of a deflection to the left, and two taps with a longer duration between them a deflection to the right. We thus have a short and a long signal, and these are represented on paper as a dot or short stroke and a dash or long one. An alphabet is constructed by a combination of dots and dashes, similar to'the combination of left and right deflections used with the single-needle instrument. The letter e is represented by a. dot, t by a dash, i by two dots, m by two dashes, and so on. Thus with combinations of dots and dashes not exceeding four in number not only any letter of the English alphabet but other sounds such as the soft German ü, ä, and ö can be formed. It may be imagined that it takes long practice to read off a Sounder with quickness and accuracy, and some telegraphists never attain the art. A skilled operator, however, can read the instrument faster than he can write down what he hears, so that the limit of speed is the rate at which a man can write. At the transmitting end the instrument is worked by the simple tapping of a key, care being taken to distinguish as in music between the length of the notes. A dash or long signal in acoustic telegraphy equals three dots or short signals. Between each of the signals making up a letter a stop of one dot must be counted, between each of the letters of a word a stop of three dots, and between two words a stop of five dots. The Sounder has many great advantages and does more work in the day than any other instrument which is not self-working. Sixty messages can be sent over it in the course of an hour, or double that transmitted by the singleneedle. In America the Sounder has displaced almost every other instrument, and though it is not so popular in England, many specimens will be seen in the instrument galleries at the General Post-Office, and the visitor may, if he likes, try to decipher the rapid tick-tick of the instrument, not, we fear, with much success.

Lady Telagraphists by Harry Furniss.

It is in another direction, however, that the most rapid telegraphy, that employed in transmitting press messages, has been developed. The alphabet of dots and dashes, (generally known as the Morse alphabet), can by means of another instrument be actually written in ink on a slip of paper at the end at which the message is received. At many of the desks at the General Post Office narrow strips of pale green paper will be seen slowly unwinding from a complicated construction which by the very ignorant might be mistaken for a sewing—machine. If one of these strips is examined it will be found to contain a series of long and short strokes in black ink. These are messages written in the Morse alphabet, and the operator will be seen cutting the strip into various lengths which are distributed amongst other operators to be written out in long hand. Thus the limit of rapidity imposed by the rate at which a man can write is abolished, since half a dozen writers can be employed on the strips discharged from one instrument. But this alone would not be of great service, since there is a limit to the speed with which the instrument can be worked at the transmitting end. It is worked by a key, and, as in the - case of the Sounder, certain intervals have to be observed; and it is found that the quickest operator cannot play off more than forty words a minute with accuracy. The invention which enables that great speed of which we spoke a short time since to be attained is one which dispenses at either end with the actual manipulation of the instrument. The ingenuity of Professor Wheatstone contrived a system by which the mere insertion of a strip of paper at one end of the line prints the Morse characters in the way already described at the other.

Automatic Telegraphy by Harry Furniss.

The strip of paper which brings about this

wonderful result is punched with holes, and

it is owing to the mode in which the strip

thus punched affects the electric current in

passing through the transmitting instrument

that dots and dashes are printed by the

receiving instrument at the other end of the

line. The punching of the paper which may

be seen going on at the Post Office at any

time, is done by means of an instrument

with three keys called the “Perforator.”

When one of these keys is struck three holes

![]() in a vertical line thus, 0 are punched on the

paper; when the second is struck one hole in

the middle of the strip only; and when the

third is struck, two holes in the middle of

the strip are punched, and also one hole above

and one below at an angle to each other,

in a vertical line thus, 0 are punched on the

paper; when the second is struck one hole in

the middle of the strip only; and when the

third is struck, two holes in the middle of

the strip are punched, and also one hole above

and one below at an angle to each other, ![]() The holes in the middle are smaller than the others, and are merely used to move the paper along by means of a star wheel in the perforator. The larger holes represent a dot when they are in a line and a dash when they are at an angle. Thus we have again the means of representing the Morse alphabet by means of these dots. The letter a, which in the single-needle instrument is represented by a deflection to the left and in the written Morse alphabet by a dot, is represented on the punched paper by two holes in a vertical line, and the figure t by two holes at an angle. When the strip containing two holes in a vertical line passes through the Wheatstone instrument at one end of the line, a dot or short stroke is printed on the green strip at the other end, and when two holes in an inclined line pass through, a dash or long stroke is printed at the other end. Thus by a purely mechanical process the punched strip reproduces in dots and dashes, perhaps a couple of bundled miles off, the identical message which has been put into the instrument. It is by this means that the astonishing rate of 450 words a minute can be attained and that we read a speech made at Birmingham or Edinburgh in all our London papers within a few hours. Even the punching is at the General Post Office made easier by calling in aid mechanical power. The keys of the machine are elsewhere struck by small mallets, but at the Post-Office the air pressure employed in the building to work the pneumatic tubes is used to work the perforator, and by this means the machine may be worked by three piano keys easily depressed by the finger. Moreover the power brought to bear is suflicient to punch as many as six strips of paper at once, while the average rate attained is about forty words per minute. Thus it requires many perforators working simultaneously to keep an automatic instrument employed, while as many clerks at the other end may be kept occupied in translating the printed tape into ordinary long hand. But the perforators can supply six automatic instruments as well as one, and thus six difierent places may be enabled to receive the message at the same time.

The holes in the middle are smaller than the others, and are merely used to move the paper along by means of a star wheel in the perforator. The larger holes represent a dot when they are in a line and a dash when they are at an angle. Thus we have again the means of representing the Morse alphabet by means of these dots. The letter a, which in the single-needle instrument is represented by a deflection to the left and in the written Morse alphabet by a dot, is represented on the punched paper by two holes in a vertical line, and the figure t by two holes at an angle. When the strip containing two holes in a vertical line passes through the Wheatstone instrument at one end of the line, a dot or short stroke is printed on the green strip at the other end, and when two holes in an inclined line pass through, a dash or long stroke is printed at the other end. Thus by a purely mechanical process the punched strip reproduces in dots and dashes, perhaps a couple of bundled miles off, the identical message which has been put into the instrument. It is by this means that the astonishing rate of 450 words a minute can be attained and that we read a speech made at Birmingham or Edinburgh in all our London papers within a few hours. Even the punching is at the General Post Office made easier by calling in aid mechanical power. The keys of the machine are elsewhere struck by small mallets, but at the Post-Office the air pressure employed in the building to work the pneumatic tubes is used to work the perforator, and by this means the machine may be worked by three piano keys easily depressed by the finger. Moreover the power brought to bear is suflicient to punch as many as six strips of paper at once, while the average rate attained is about forty words per minute. Thus it requires many perforators working simultaneously to keep an automatic instrument employed, while as many clerks at the other end may be kept occupied in translating the printed tape into ordinary long hand. But the perforators can supply six automatic instruments as well as one, and thus six difierent places may be enabled to receive the message at the same time.

In practice, the simultaneous transmission of messages is carried still further. A certain circuit, containing perhaps five towns, is supplied with automatic machines. Whenever the machine in London is fed with the punched ribbon each of the other towns receives the green printed slip at the same moment. For press work this arrangement is invaluable. Messages are handed in by some news agency like the Press Association to be sent to a string of country papers, and to various exchanges and news-rooms besides. Many of the towns are on circuits supplied by the automatic instrument. Six of these circuits be set in motion by the work done by one perforator, and each flashes the news to a circle of four or five towns at the same moment. At the provincial post-office the telegraphist knows from the nature of the message and the instruction sent with it where it has to be delivered, and, as quickly as men can write, the news is disseminated through the town to the various papers and institutions entitled to receive it. One instrument which dispenses with the use of any artificial code is to be seen at the Post-Office. This is known as Wheatstone’s A B C instrument. It consists in appearance of two dials like the face of a clock, round each of which the letters of the alphabet are inserted. One dial is used for sending, the other for receiving, messages. On the sending dial each letter is supplied with a key, and below it is a handle. When the handle is turned and one of the keys depressed the pointer on the dial revolves and stops opposite the correspond ing letter, and at the same moment at the other end of the line the pointer on the indicating dial points to the same letter. Thus any one who can spell out a word can work the instrument, and it has consequently been found very suitable for private use,—for example, in connect ing a private house and a place of business, where the telegraph is worked by ordinary clerks and servants. It is, however, very slow, the average rate of working not exceeding five words a minute, and it is also expensive, for though simple in visible working its mechanism is exceedingly delicate and complicated. It is being rapidly superseded for private use by the telephone, and will probably soon be confined to a few small village post-offices where few messages are sent and no trained labour can be employed. The instrument is interesting in one respect that it is worked entirely by electromagnetism without the aid of any galvanic battery.

There is another direction in which telegraphy is developing. Means have been found by which messages may be sent over the same wire in contrary directions at the same time. Thus, while London is speaking to Birmingham, Birmingham may, over the identical wire, at the same time be speaking to London. This is called duplex telegraphy, and instruments working on this principle may be seen at the General Post—Office. Even this wonderful arrangement has been improved upon, and by means of what is called quadruplex working, the same wire may be utilised for two messages in each direction; and in America a Mr. Delany has even invented a multiplex instrument by which six messages may travel simultaneously over the same wire in one direction or the other.

Keeping Time by Electricity by Harry Furniss.

The economy of posts and wires resulting from such inventions and from the rapidity with which messages are now transmitted is shown by the fact that an increase of more than 300 per cent. in message work has necessitated an increase of only 150 per cent. in mileage of wires. And this is no trifling con sideration. For not only are posts and wires expensive things, but there are many difficul ties in carrying them from point to point. A line of telegraph in England is in a some what similar position to a sewage farm; every one acknowledges it to be the right thing, but every one objects to its presence in his immediate neighbourhood. The gentle— man who finds it the greatest convenience to have a telegraph station in the village within half a mile of his house, yet objects to the intrusion of a single post inhis drawing-room view, and will not allow his park trees to be lopped to allow a wire to be carried along the adjoining road. Every one is prone to resort to the cry that the wires should be placed underground. But not only is the expense of this process often ten times that of erecting an overhead line, but in long distances any considerable length of under ground line sensibly retards the speed of working. Fortunately the feeling is not quite so strong as in the case of sewage farms, and the Post-Office is mostly able by the exercise of some ingenuity and diplomacy to meet reasonable objections and overcome unreason ing opposition. But any one who enables two messages to be sent over a wire where only one could be sent before, deserves from the telegraphists the same species of praise which has always been accorded to the man who doubles the productiveness of the earth. Other forces besides electricity are called in aid in the conduct of practical telegraphy.

The Central Telegraph Oflice is connected with all the district offices and some other metropolitan centres by tubes, through which small packets are blown in one direction and sucked up in the other. For transmission through these tubes half a dozen messages are taken together, rolled up, and placed in a small leathern pouch like a dice-box with an elastic band across the top. The dice box is put in the mouth of the tube and is forthwith shot to its destination in a few seconds. So great is the saving of time and labour effected by this pneumatic despatch, that the tubes have lately been provided with a room to themselves, so that they and the telegraph instruments may each have freedom to develop without encroaching on the space required for the other. In Paris and Berlin the system is Still more popular, a kind of express post being organised in each place. In London the tube plays a leading part in the transmission of foreign messages. Nearly all the offices of the foreign cable companies are connected in this manner with the General Post-Ofice; and some six thousand messages coming from or destined for abroad are blown along their journey to and from the Central Office in the course of a day. The longest tube, however, is that between the General Post Office and the House of Commons. It is more than two miles long, and the journey occupies six minutes. The total length of tube in London now exceeds 32 miles.

It seems almost anomalous to speak of telegraphic work and not to mention the telephone. There are, however, no telephones to be seen in the Post Office galleries, for this instrument does not at present occupy any prominent place in the Post-Office system. We all know that it enables two persons to talk directly to each other without the aid of any signal or the manipulation of any instrument. That it must have a great future cannot be doubted, but at present its use is confined to private connections between house and house, and to the institution known as the exchange. The exchange is of the nature of a club. A certain number of persons subscribe to it, and any two of these persons can at any time be put in a position to talk to each other. The Post-Office has twenty seven of these exchanges, that at Newcastle on-Tyne being probably the most perfect specimen of an exchange in England; the private telephone companies, which are licensed to carry on business by the Post master-General, have many more. But the total number of telephone subscribers in England is only about 20,000, and there are more than half that number in New York alone. Saving of physical labour is much more important in America than at home, on account of the greater heat of the climate and the higher rate of wages for unskilled labour.

Pneumatic Tubes at the Central Post-Office by Harry Furniss.

In addition to the conversion of ordinary letters into the Morse alphabet many devices are employed by the Post-Office to facilitate the sending of messages. Thus it is of course necessary to note the time of handing in a message, so that it may take its proper turn. But as figures are indicated in the Morse alphabet by combinations of five signals, while letters never require more than four, it is found economical to construct a code of letters to note the time. For this purpose the twelve hours on the clock are indicated by the first twelve letters of the alphabet, J being omitted, and the same letters are used to indicate the twelve periods of five minutes. The intervening four minutes are in each case denoted by the letters R S W X. Thus by means of three letters any time may be indicated. A, for example, sent alone means 1 o’clock, but AA means 1.5, while AB means 1.10, and ABS means twelve minutes past one. In addition to the time of handing in, many other items of information have to be telegraphed with each message besides its actual contents. Thus it is necessary in the first place to tell the receiving ofiice whether the message handed in is an ordinary message paid for by the public, a foreign, or press message, one on the service of the Post-Office, or one transmitted free by arrangement with a railway company or Government Department. It is also necessary to say whether the message is one for delivery from the receiving—station or for retransmission by telegraph to another. For in all these cases separate forms have to be used in taking down the message. Accordingly a letter such as 1, which indicates that the message is an ordinary one for immediate delivery, or a combination of letters such as SP, which indicates that it is a press message, must be sent over the wires to prepare the receiving clerk at the ofiice of destination. This letter or combination of letters is called the prefix. Further, the message, in order to insure accuracy, and the instructions as to the mode in which the message has to be delivered; and these several signals together with the prefix and the code-time are known together as the preamble of the message.

Before even this preamble can be sent the office for which the message is in tended has to be “called up.” When only two stations are in communication the separate forms have to be used in taking down the message. But when several stations are connected by the same wire, the attention of the particular station for which the message is destined must be secured. This is done by signalling, not the full name of the station, which would occupy time, but an abbreviated name, consisting of two or three letters, assigned to that particular station and known as its code name. Thus LV is Liverpool, EH Edinburgh, and so on. It will be seen that much work has to be done before any part of the message handed in by the public is flashed over the wires. Moreover the simple transmission of a message in one direction is in many cases not deemed enough to insure accuracy. When the more common instruments, such as the single-needle, are used, and the operators are not specially expert, every word is acknowledged by a distinct signal sent back by the receiving to the transmitting office, and figures are always repeated in the reverse direction to ensure accuracy. There is also an elaborate system of accounts, the message-forms handed in by the public being carefully checked at head-quarters with duplicates of the forms on which messages are delivered in order to see that all proper charges have been made and accounted for. The handed-in forms, or original telegrams, are kept for three months, during which time the Post-Office will produce them to the sender and receiver, but to no one else. They are subsequently converted into pulp by a machine such as that shown in one of our artist's sketches — an apparatus which receives telegrams at one end and at the other gives out a thick white fluid, which again, under the pressure of heavy rollers , forms sheets of a soft dirty- grey material. Forty-one tons of telegrams can be thus pulped in a month.

It will be seen from this slight sketch of telegraph-working , that what the public hava been in the habit of getting for a shilling is far more , from the point of view of the Post Office, than the mere transmission of twenty words. In the first place, until recently, the addresses of both sender and re ceiver, which , on the average, extended to eleven words, were transmitted free of charge. Beyond this must be taken into account the preambl, comprising on the average six words; the calling up of the proper office, and the acknowledgments and repetitions necessary to insure accuracy of transmission, besides all the checking and account-keeping necessary in an enormous business. People who talked of the possibility of sending a shilling tele gram for sixpence, and spoke in that light-hearted way, with which we are all familiar, of the timidity and want of enterprise of the Post-Office, and the certainty that large profits would accrue from low prices had of course no knowledge of the amount of work which each message represents. Nevertheless the demand for a cheaper telegram was reasonable enough, and was from the first favourably viewed by Mr. Fawcett. When the tele graphs were transferred to the State in 1870 the number of ordinary messages telegraphed in the year was 9,000,000. In the year ending March 1885 it was thirty-three millions and a quarter. This is an enormous increase, but it took place mainly in the first ten years of the Post-Office administration. During those years there was an increase of twenty millions, while during the succeeding four years the whole increase was less than four millions, and what is more ominous the rate of increase tended to diminish year by year, the increase of 1884-5 being little more than half that of the preceding year. It is true that the number of telegrams sent in England, per head of the population, has always com pared favourably with other countries. But then the number of letters sent in the United Kingdom is very much greater than in other countries, and judged by this standard, the telegraph has not been used to the extent which might have been expected. Thus in the United Kingdom each person sends forty letters in the course of the year, and in France only fifteen. But the proportion of telegrams to letters prior to the introduction of the sixpenny telegram was in England one to forty-four, while in France it was one to twenty-nine. All these facts pointed to a failure on the part of the telegraph to attain that popularity which might fairly be expected. Parliament, taking this view, in 1883 insisted, against the faint protests of the Government, upon a reduction in the minimum charge for a telegram to sixpence; and the new system with which we are now all familiar, came into force on the 1st October, 1885. There was a lively controversy over the abolition of free addresses, before Parliament, at the instance of Mr. Shaw-Lefevre, was induced to sanction the step; but it may fairly be said that the arguments for the change bore down all opposition by their superior weight. Under the old system there was no inducement to shorten either addresses or message, and the wires were constantly burdened with the transmission of useless matter. Now nothing is sent but what is necessary, and every word pays toll.

It was in expectation of the sixpenny telegram that the additional story at St. Martin's le-Grand was built, and a new room devoted entirely to pneumatic tubes. This additional space was not provided too soon, for the number of messages sent has increased by more than fifty per cent. since the reduction of charge. One can imagine the keen interest with which Mr. F awcett would have watched the effect of the new mode of charge; and, mingled with regret that he cannot chronicle for us the result of the reform which he did perhaps more than any one else to bring about, must-be the wish, always present to his mind, that such agencies as the Post-Office and the telegraph may, not only by their direct operation, but by their more subtle influences on the production and distribution of commodities, continually tend to make life go more smoothly with all classes of the community, and especially with the poor and struggling.

Homepages for Related Material

Bibliography

“Post-Office Parcels and Telegraphs.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 5 (1887-1888): 738-51. Hathi Trust version of a copy in the Pennsylvania State University Library. Web. 23 January 2021.

Last modified 25 January 2021