Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

[In transcribing the following essay from The English Illustrated Magazine I have followed the invaluable, but here often very rough one found in the Hathi Trust online version. — George P. Landow] .

All the materials used at the potteries are, save one, brought from some distance. The blue clay comes from Poole Harbour, once made fashionable by the “Lord of the Island;” the white china clay and china stone come from Cornwall. The bones used for fine porcelain as the cheapest and best form of phosphate of lime come from the great saladeros of South America, where hecatombs of beasts are slaughtered daily. Flint also comes from a distance. There is therefore no reason at all why the potteries should exist where they are, except that a certain coarse clay, used for “saggers,” or cases for holding crockery in the kiln, is found there in great abundance. This coarse clay doubtless determined the original establishment of ceramic work near Stoke, Hanley, and Longton, and formed the material of the clay pots for honey, butter, and other produce, which Holcroft, the author of The Road to Ruin, helped a master to hawk round the country before he became first a jockey, and having failed at that superior trade, a dramatist and general literary person.

The other materials used for earthenware and porcelain appear to have gravitated towards the area in which the coarse Stafiordshire clay supplied brute basis for pots. The enormous quantity of the latter a used for “saggers” may be guessed from the excavations near Hanley. It would cost a vast sum to convey the annual requirement of the potteries for “saggers” to any great distance, as much perhaps as all the actual constituents of china and fine earthenware put together. Some of these arrive partially pre pared, others in a completely raw condition. For instance, the kaolin or china clay is purified at St. Austell's, where it is dug, or rather washed from its bed. Both this Cornish clay and Cornish stone are simply the silicate of alumina known as felspar in difierent stages of decomposition. These require no more preparation when they arrive at the potteries than allowing the stone to remain some time in the open air before use. At the works of Minton's (a private limited liability company) immense blocks of this stone may be seen piled beside the canal which has brought them thither. The grey or blue clay from Poole is used in far greater quantities at the potteries than these precious materials, and may be said to bear the same relation to earthenware that kaolin does to porcelain. It is a silicate of alumina like the other, but contains a smaller proportion of the valuable alumina. Pure silica is seen in the familiar form of flints, heaped high in great irregular cairns by the side of the craggy masses of Cornish stone. There is a tremendous bone house too at Minton’s, where bones are used in large quantities for porce-. lain. Both flint and bones require considerable preparation. Both are calcined before being ground in a. mill with water to the extreme fineness required. Every organic constituent of the bones is completely burnt out, so that there remains only the mineral ash, mainly phosphate of lime with a little carbonate of lime and magnesia. Beside the canal, where lie heaped many of the constituents of fine porcelain and earthenware, are the grinding mills. It is not, I believe, customary for all potters to calcine and grind their materials, but it has long been a custom of Minton’s to do so. Hence crushing-machines and mills for reducing Cornish stone, flints, and bones to a smooth white paste, and a colour mill for grinding the mineral pigments used in printing and painting the potter’s work. It is obvious that extreme care and scrupulous cleanliness are needful at every stage of manufacture. When the various materials are mixed they are as white as milk and much freer from impurities than that article of food as commonly vended.

The process of mixing takes place in the slip house as it is called. For earthenware all the ingredients I have enumerated are used in various proportions except the calcined bones, which are only used for porcelain. To earthenware the blue clay gives toughness and solidity, flint gives whiteness, kaolin whiteness and porousness, and Cornish stone acts as a sort of flux binding all together. These materials being weighed and measured, are placed together with a large quantity of water in huge vats fitted with an agitator called a “blunger,” by which they are thoroughly stirred up and mixed together. As my courteous guide raises the lid of one of these “blunging” machines, I descry, as it were, the interior of a vast churn filled with a strong white sea, as if the cliffs had get mixed with the tide in the manner depicted by some painters of seascapes. This beautifully white fluid runs off when its parts are judged to be sufficiently mixed, into troughs, and is strained through sieves of lawn, varying in fineness from twenty-two to thirty-two threads to the inch. It is next tested by weight, a certain measure being required to weigh a certain number of ounces. The slip now reposes for a while in quaint receptacles shaped like the Noah's ark given to children. To get rid of the superfluous dampness of the compound “slip,” it is forced by means of pumps into bags of strong cloth. It is then pressed, and sometimes cut up and pressed again, being then ready for the thrower.

The Thrower. From a Drawing by A, Morrow.

This is hardly the place in which to descant upon the potter’s wheel as used by the Egyptians. Sufiice it to note that the main distinction between the modern and the ancient potter is that the latter turned his wheel with his foot while his descendant is supplied with motive power by steam. When the sort of sausage machine just described has done its work and the slip has been pressed, the material is of the consistence of stiff dough. In this condition it comes into the hands of the potter, but not directly. Before it reaches him it is weighed out in lumps and handed to him by the girl who acts as his assistant. When the lump of clay is finally handed to the potter he deals with it in a wonderful manner. Placed on the horizontal wheel revolving before him, the clay is made to perform the most extraordinary evolution. It spreads out, leaving a hollow centre, and grows like a mushroom under his skilful hand. It becomes anything he likes. It may be a bowl, a cup, or take any other shape. As the clay revolves rapidly the workman has only to change the position of his hands to produce any shape he may wish. To an imaginative person this is the prettiest part of the manufacture of earthenware. It is incredibly rapid. The workman has hardly his piece of clay placed before him by the girl attendant than he spreads it out and draws it up as if by magic. There are many industrial operations picturesque enough, nay, really grand in effect. Grand effects are to be got from smelting furnaces and rolling mills, the working of an emigrant ship out of harbour, the landing of a great catch of herring, mackerel, or pilchard, and beauty may be sought in the ever lovely picture of loading and carrying corn——but for sheer prettiness and swiftness, the potter’s wheel still holds its own. The whole proceeding is so rapid, the touch of the workman so clever, that it is just a little be wildering. One stands and wonders whether one could do it one’s self by the aid of the outer and inner gauges, which appear to be the only aids to the workman beyond his fingers to throwing by the dozen cups of the same size. The principle of the potter’s wheel, that of making the article to be operated upon while some kind of tool is held against it in one fixed position, is carried out in many departments of pottery.

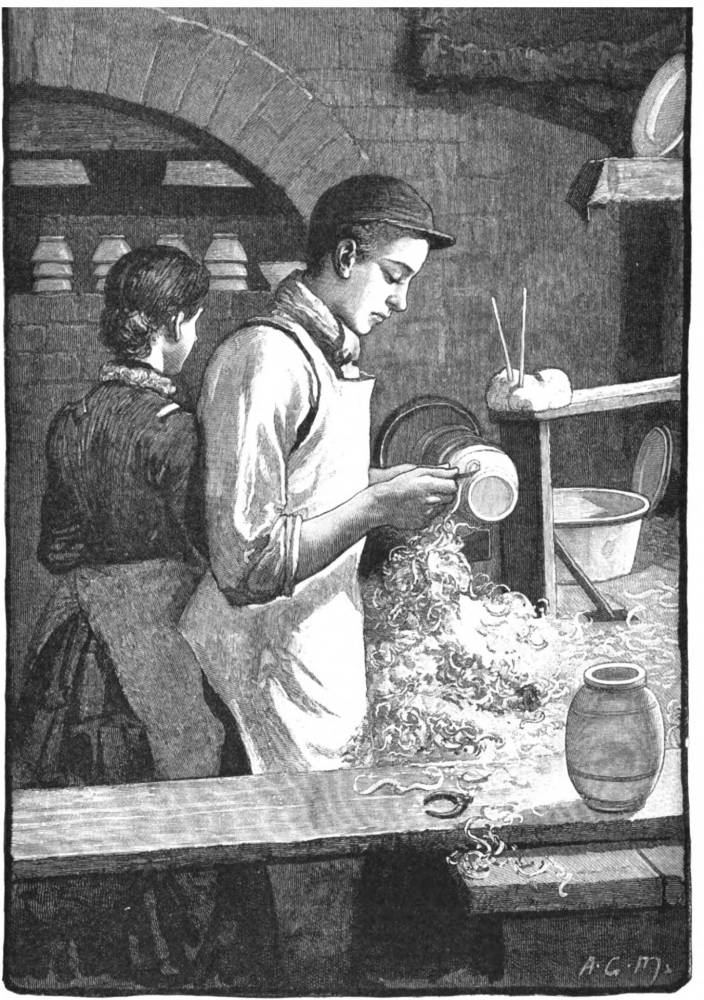

In the turning room many articles thrown on the wheel are finished by the ordinary process of turning—once, by the way, made fashionable in royal families by Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Émile, a work of great influence in its day, albeit it did not, like the Contrat Social, attain the distinction of being bound in the skins of aristocrats tanned under the first French Republic at Meudon. Pressing or moulding is perhaps a more modern kind of work, and is applied to plates and such objects as hardly need to be thrown or turned. A workman makes what is technically called a “bat,” that is a pancake of slip out of the material weighed out to him, and this is moulded into the form required by pressing a profile or mould upon it while it revolves on a rotatory frame called a “jigger.” What is called “handling” is done in a room in which a kind of duplex operation is carried on. Handles for milk jugs and such like vessels cannot be thrown upon the vessels, which thus must be “handled” afterwards. Handling material, slip like the rest, is pressed through a tube, and is then cut off in lengths by the workman, given the requisite curve by his deft hand, and united to the jug by a little liquid slip applied with a brush. It is said that handles sometimes break but never “come off” at their point of attachment.

In addition to throwing, turning, and pressing, there are in other rooms of Minton’s great manufactory carried on operations such as moulding and casting on a large scale. It is the pride of the potter to produce a large piece. He is not satisfied with any piece which requires the support of a gold rim or collar — that, he insinuates with a shrug of the shoulders, was cast and fired in bits and united by the ormolu. Consequently it is not good pottery like the old Japanese pieces and the big work of Minton’s — the storks and cranes and peacocks were all fired in one piece. Nevertheless these objects are very often moulded or cast in several pieces which are afterwards bound together before they are dry, and are submitted to the kiln. The various sections are united by a thin roll or band of slip, no sign of which is permitted to appear, and perfect cohesion is ensured by all being fired together. In making Parian and some other figures, liquid slip is poured into moulds, and the images are produced in a manner like that employed for plaster or bronze.

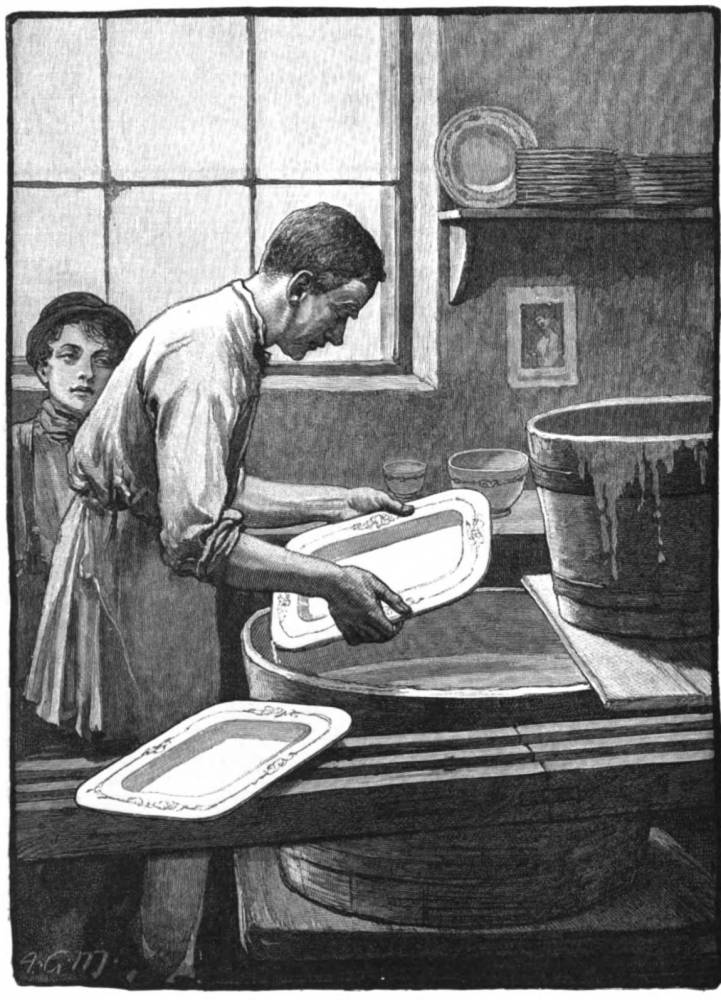

Left: Turning. Right: Dipping in Glaze.

In the so—called “greenhouses” a large quantity of ware is drying preparatory to being “fired.” This process is the crucial test of pottery. All the preceding operations have been carefully conducted with a distinct view to this one. All the combinations of clay, flint, stone, or bone have been made with forethought of the kiln in which the ware will be partially vitrified. Earthenware and porcelain are only, as is well-known, less perfect forms of glass, or rather of glass in another stage of development. When the earthenware slip cups and saucers, mugs and jugs, are sufliciently dried, they are ready for the “biscuit” kilns as they are oddly called, for the ware is not twice baked in them nor is it good to eat. Some kinds of ware are submitted to the intense heat of the kiln three times, all twice—once in biscuit and once in glaze. When painting is introduced over the glaze, as in the old Sèvres paté tendre, and the various kinds of fine porcelain, there is a third firing. Before being placed in the kilns all the articles thrown, turned, or moulded are arranged in the “saggers,” receptacles of coarse clay, very thick and strong, like deep pie dishes.

Into these the various articles are packed with considerable skill, little triangles being placed between each to prevent their touching each other, and the saggers are next packed together in the kiln or oven, each sagger being lined at the bottom with a layer of rock sand. Piled one on the other the saggers make a fairly compact column, and when the oven, some nineteen feet in altitude is filled, the fire is applied. It will be understood that the fire by no means touches either the ware or the saggers in which it is inclosed. They are simply in an oven about to be raised to a tremendous heat. The firing is done by means of flues so arranged as to diffuse intense heat throughout the whole interior of the ovens. This firing is a ticklish operation requiring the supervision of a skilled workman capable of existing without sleep for some thirty-six or forty hours. At first the heat is applied gently for fear of cracking the ware, and the fireman has an anxious time of it. Little openings in the brickwork enable him to judge of the progress of his work. The heat of a biscuit oven during the last twenty-four hours is intense, between twenty and thirty thousand degrees of Fahrenheit. As the ware has taken from forty to fifty hours in firing, so does it require an equal time to become cool. In this condition it is sorted by girls and stacked in immense warehouses. Technically it is “biscuit” ware, and is susceptible of a great variety of treatment. It may be painted or printed on at once, that is “under the glaze” as it is called, or before the metallic glaze is applied, or it may be painted over the glaze, or the regular pattern may be produced in one way, and the floral design, the variable handiwork, in the other. Every body has been made familiar with biscuit ware by Sèvres and knows the aspect of this half-made china, minus the glaze and the subsequent firing. Of decoration it may be roughly said that oriental work such as Nankin is all under the glaze and indestructible by fair wear and tear, while Sèvres is over the glaze, and majolica is painted “in” the glaze itself, is in fact a coloured glaze employed as pigment. This being stated, it will be seen that biscuit, so-called because it has only once been tried in the furnace, has before it various destinies.

Printing Transfers.

The printing under the glaze, always employed for ware subjected to severe friction, and consequently requiring the protection of the highly vitreous glaze, is an interesting process conducted in large rooms filled with women and girls, all active and bright as seen by a glimpse of wintry sun. The designs for the various patterns are engraved upon copper plates, of which there is an array in one room at Minton's which must have cost a very large sum of money. In printing on crockery of any kind it is necessary that the process should be per formed rapidly. When the design has been produced upon a copper plate, it must be transferred, first to a piece of thin, tough paper, and thence to the biscuit ware. To those familiar with the operation of printing etchings, it will hardly be necessary to explain that warmth is necessary to success full transfer. Still more is a high temperature essential to the charging of the plate for earthenware with the mineral pigments alone possible for such work. As the skilled workman stands at his desk to print the papers required for transfer, plate and pigments are alike hot. Very swiftly he charges the plate with sufficient pigment, cleans it off, and prints off rapid impressions. These the numerous women and children filling the room apply at once to the earthenware, the porous biscuit at once absorbing the colour. The work, however, requires some little neatness of hand and quick rubbing down with a flannel roll. The thin tough paper charged with hot pigment adheres to the porous plate, which at once absorbs the latter. Immediately the paper is washed off, leaving the design on the biscuit from which it will not wash off on account of its oily character. Useful thus far, this oiliness would prove a serious impediment at the next stage of operations. No glaze would be absorbed by the part of the biscuit covered by the design, and it is therefore necessary to get rid of the oil. This is done by baking the were in an oven just sufficiently heated to destroy the, oil without damaging the colours.

The were is now ready for the dipping-house, in which are vessels full of liquid glaze—literally a form of glass, ground to exquisite fineness. Dipped into the glaze the porous biscuit greedily absorbs it, and the ware is packed in saggers which have been washed out with phosphate of lime. Fifteen or sixteen hours’ firing at a lower temperature than that of the biscuit oven suffices to complete this part of the process, and in the case of ware ornamented only under the glaze, finishes the potter’s work. In many cases however, overglaze work is added, and this is done by women and girls occupying a range of large rooms high up in Minton’s factory, and very pretty to see on a bright morning while work is going briskly forward. These are all work women, be it understood, not artists, and merely fill in the colours according to the design marked out for them, work requiring attention and neatness, but no inventive power or skill in drawing. The colours laid on, it is almost needless to mention, are what are called enamel colours, all made from metallic oxides with turpentine, tar, or oil of aniseed as a medium. Beyond the painting shops are those occupied by the gilders, who complete the ornamentation of the ware, after which it is again fired for about six hours at a red heat. This final firing is an important part of decorated pottery. Many of the colours change entirely during the operation, the greens and reds being the most constant to their original hue. Then the gilding requires to be burnished with agate or bloodstone burnishers, and the surface of the ware generally to be sandpapered till it is free from any trace of roughness. One kind of mark or defect nearly always leaves its trace, generally easy enough to detect by the naked eye. This is the impress of the little tripods known as “spurs," which are placed between the pieces in the kiln to prevent them from touching each other. The spur-mark is rubbed down and removed as far as possible. When the ware has reached this stage it only requires to be sorted, an operation needing some care and a quick eye, inasmuch as some of the mineral colours employed change greatly in firing. Not only do they change, but in degrees varying greatly according to the intensity and duration of the firing. The standards of colour kept at Minton’s demonstrate the variety of shades to be obtained, for instance, of a certain oxide of iron, which yields not only many differences of strength, but of actual hue, according to the degree of firing applied to it. The “flown” were, as it is called, is that printed or painted with these “false fleeting,” but very convenient pigments, and requires “sorting” accord ingly, the lighter coloured pieces in the one set, and the darker in another.

The slight and rapid description just given of the various processes of making earthen ware will almost suffice for that of the tiles and china. with which Minton’s name is intimately associated. Tiles are made under enormous pressure, the aim being to render them indestructible. When the body of the tile has been thus made and subsequently fired, the tiles are printed by the “transfer” process already described, and hand-painted if necessary. The designs for tiles are often by artists of eminence, such as Mr. H. Stacy Marks, R.A., who drew The Seven Ages of Man. The china-works have slight differences from those carried on exclusively for the making of earthenware, the fundamental difference in the “slip” being the large proportion of phosphate of lime or calcined bones employed in the former, and entirely absent from the latter. The slip too is “wedged,” that is, cut in pieces or strips and pounded so as to drive out, if possible, any air which may have become inclosed in its substance. There are too, difierences in throwing, pressing and moulding, too minute to be dwelt upon. Altogether, the work is far more ticklish than that of making earthenware, from the short nature of the paste or slip. Great skill is required in the modelling room, when vases of different form requiring what is called “undercutting,” are to be produced. The enormous value of some of the pattern pieces lent by the courtesy of liberal collectors to Minton’s has at times proved a fearful joy. One of Sir Richard Wallace’s vaisseaux à mât in old Sévres was kindly lent by him to Minton’s and proved a thing of terror. The reproductions of such work are made by slip casting, a process like any other casting, but requiring especial delicacy.

Among The Kilns.

From imitation, however clever, to original design, is a wide step, but not perhaps in the opinion of the technical potter, who prides himself on the greatness of his pieces, and the skill displayed in overcoming difficulties of form. In detail there is great difficulty in reproducing the colours, the rich redundancy of glaze feeling “like the touch of a baby's hand,” as Mr. Gladstone put it, and the massive gilding of old Sèvres, the latter of which has a thickness as fine as pâte tendre, almost suggesting the massive character of a mount. This “lumpy” gilding, and luminous because not uniform, sur face of turquoise and gros bleu, Minton’s have become very successful in imitating. But these technical triumphs only supply setting for the exquisite pictures supplied by the department under the direction of M. Arnoux, a member of Minton's private company. During long years M. Arnoux has presided over the department of hand-painting on china from original designs made by him self and his colleagues. These gentlemen go like other artists to Chatsworth and Rangemore, to cornfield, coppice, luxuriant river side, yellow bogland, and purple moor to seek inspiration for the subjects they limn in indestructible colours. Large life-size sketches made in the open air are reduced in the atelier of M. Arnoux to the dimensions prescribed a by the centre of a plate or the side of a vase. The beautiful turquoise blue and other colours used in the exterior ornamentation are simple matters compared with the delicate hues employed in the medallions. Many of these are studies of flowers, others, figure subjects, some from picturesby Boucher, Watteau,or Greuze. Much of this work is exceedingly costly, rivalling in prices the original charge for royal Sévres. M. Arnoux, with his able assistants, produces work worthy of note in every section of his department. The hand painted dessert-services are marvels of skill. and the number of richly decorated vases annually produced is very great.

A special department is that of M. Solon, whose work, pâte-sur-âte, has during the last few years excited extraordinary attention. Many more persons are familiar with this rich and delicate cameo-like work than understand how it is done. The mind naturally seeks analogies, and perceiving the effect of a cameo, and that of the ware named after M. Solon, supposes that a stratum of semi-diaphanous white paste is laid upon the dark green or olive coloured vase, and carved away by the artist as he would the lighter seam of sardonyx. The greater degree of transparency is attributed to the lower degree of relief, not without reason, save that the white paste is by no means laid on the other and treated like a cameo. M. Solon who is found himself at work among his assistants shows his visitor at once that nobody is less of a cameo or relief engraver than he. In fact he simply takes advantage of the semi transparency of the so-called parian or kaolin material to convey the highly prized effect obtained from onyx, sardonyx, or shell by taking advantage of variously coloured strata, just as the cunning goldsmith adapts his jewel to the shape of the strange and barbaric pearl. M. Solon’s method might be more accurately described as a heavy impasto or as modelling in very low relief. M. Solon having previously made his design, stands before a vase, and with a pencil puts on the thick white paste he employs. The beautiful effects pro duced are due to the varying thickness of this china slip. For delicate diaphanous draperies it is reduced to extreme tenuity. For the bolder modelling of the figure it grows thicker and thicker until it becomes as opaque as its dainty quality permits. Laid on with a brush, the slip is capable of subsequent manipulation by modelling tools, but in its essence, M. Solon’s work is painting with china paste on other paste. It is not engraving in relievo, and has, except in its charming effect, no analogy with gem or cameo engraving. The bolder portions or “high lights” are not laid on in bulk at once, but are gradually thickened as the artist sees that they require to be strengthened.

Other rooms under the direction of M. Arnoux are occupied by skilled artists engaged in producing every kind of ware decorated by hand. In little rooms they sit bent over their difficult work, for they cannot, except by the eye of practice, see what they are doing. And, it may be added for the benefit of art students, that painting on round and hollow surfaces is not quite the same thing as painting on canvas. The consequences of a mistake are far more serious, and the awkwardness of the position far greater. When it is considered that dessert services are roduced of which every plate is worth 20l, the care expended on this kind of work may be imagined.

In the show-room of the great factory may be seen every kind of successful pottery produced at Minton’s up to this moment. There are grouped together immense figures of beasts and birds, the triumphs of pottery, and with them the results of many attempts to rival the old Sèvres tints, turquoise, rose Pompadour, and gran bleu. Not the least interesting are the modern imitations of the wondrous faïence d’ Oiron or Henri Deux ware as it is called in this country. The curious discussion as to whether this costly ware was produced by means of “transfer” or by inlaying, was set aside by the experiments made at Minton’s by inlaying with coloured clays. There is now no doubt. from the reproductions exhibited, that the famous ware was a species of ceramic marqueterie in which a yellow body was inlaid with coloured clays placed in incised lines like niello in metal work. In pottery, however, the operation requires more care than in metal, for the variously coloured clays shrink unequally. Costly now as at all times, in great disproportion to the effect produced, the ffaïence d’ Oiron is not likely to become as popular as the Minton's reproduction of the majolica and other famous wares, or the beautiful statuettes in Parian ware. The rarity of the old Henri Deux were probably arose from its extravagant cost, and the same reason militates against its reproduction in any great quantity. Perhaps it was the result of misdirected ingenuity, and is rather a proof of the potter’s technical skill than of his success in producing one of those things of beauty which are joys—not for ever, but until “neat-handed Phyllis" brings them to an untimely end.

While looking at the enormous quantity of ware of various kinds in the hands of the packers who cleverly pile it in barrels, hogs heads, and crates, it is difficult to realise that good earthenware in great plenty is one of the most modern of popular luxuries. It was only in our grandfathers’ day that the wooden trencher and the pewter platter made way for the willow-pattern plate, and new the productions of the English potteries are found all over the habitable globe, while “bits” of old battered pewter are sought for that they may be like “bruised arms hung up for monuments.” On the continent of Europe the million was no better off not withstanding the lustre-ware of Gabbio and the turquoise blue or rose Pompadour of Sévres. In the Eringer Thal and other remote villages of the Alps was to be found only the other day, perhaps the most primitive form of table equipage, consisting of a solid table like a butcher’s block with holes scooped in the upper surface to hold the soup or stew on which the hardy natives subsisted, and I fear that even now it would be possible to find in the mountains of Kerry or on the wild coast of Connaught cabins destitute of any vestige of that great promoter of cleanliness and care, good crockery.

Related Material

Bibliography

Becker, Bernard H. “China-Making at Stoke-on-Trent.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 2 (1884): 781-90. Hathi Trust version of a copy in the Pennsylvania State University Library. Web. 3 January 2021.

Last modified 5 January 2021