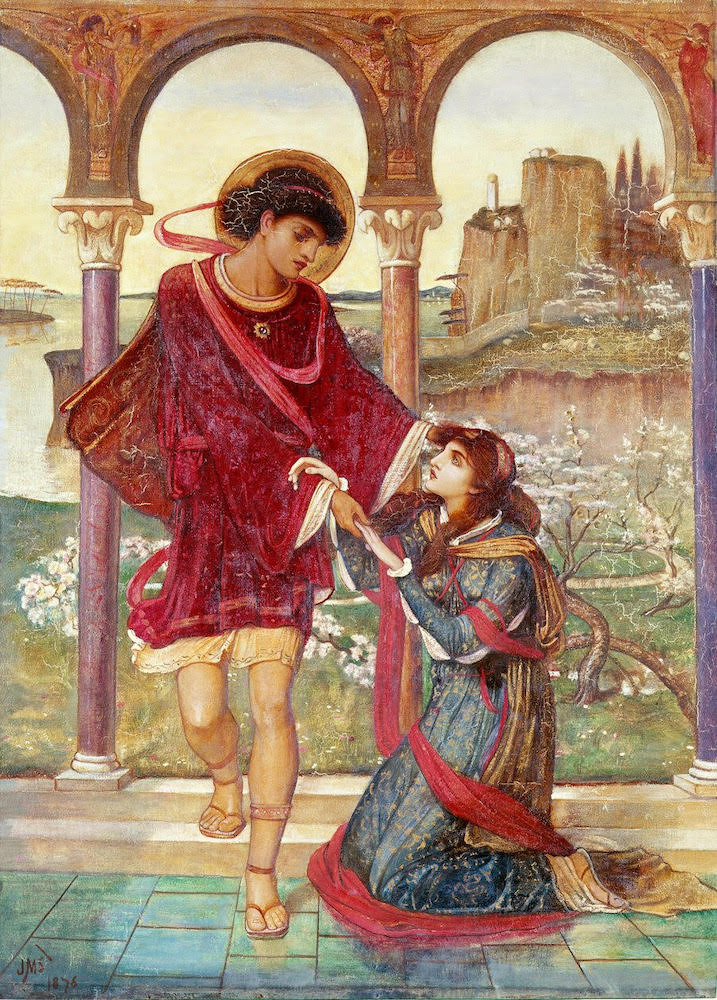

The Annunciation, by John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937). 1876. Oil on canvas. 22 x 16 inches (56 x 41 cm). Private collection, image courtesy of Sotheby's, London. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

This early work by Strudwick is of particular interest because it shows the obvious influence on his work of J.R.S. Stanhope, an artist for whom Strudwick had previously worked as a studio assistant and who remained his lifelong friend. Although depictions of the Annunciation have been common in art since the Renaissance, and were particularly favoured by the Pre-Raphaelites, Strudwick's is a most unusual interpretation with little of the normal iconography expected in such a subject. The biblical story is well known: as told in the gospel of Luke I, 26-38, the archangel Gabriel appears to Mary at her father's home in Nazareth to tell her she has found favour with God and has been chosen to bear his son. The scene depicted by Strudwick does not show a humble home in Galilee, however, but appears more like a palace situated in Renaissance Italy. Mary is clad in rich clothing and not the humble garments that one would expect of someone of Mary's social position in biblical times. Instead of recoiling in awe at being visited by an angel, she is kneeling and reaching out her hands to him. Unlike more conventional depictions of the Annunciation, Mary has no halo nor is she seen reading from the book of Isaiah in which the Prophet foretold the Virgin birth. The holy dove, so frequently shown as a symbol of the descent of the Holy Spirit, is also absent, as Christopher Newall points out (68). The archangel Gabriel is identifiable only through his halo but lacks his wings and he is not carrying attributes like a lily or an olive branch with which he is frequently portrayed. His robe is a rich red colour and not the white garment symbolizing purity in which he is generally portrayed. In fact, if it were not for Gabriel's halo, one would be hard pressed to identify this as an Annunciation subject at all.

However, it is not without its symbolic touches. The almond tree in bloom in the background was probably chosen because, in the language of flowers, almond blossoms symbolize rebirth, hope and new beginnings, an appropriate choice when Gabriel's appearance foretells the birth of Jesus, who will become the saviour of the world. In the Middle East an almond tree might be the first tree to bloom but it is the last to bear fruit. Strudwick is not known to have been particularly religious, but he did paint a number of religious subjects during his career. Newall comments specifically on this point, presuming that the artist would have been "encouraged to follow Anglican observations at St. Saviour's Grammar School, where he was educated," and that his subject here "may indicate that he was devout at that period, while the reinvention of the theme in terms that depart from Catholic iconography is in keeping with attitudes of Protestant artists in the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic circles from the mid-nineteenth century onwards" (68).

Newall has also discussed the ways in which this early work differs from his later paintings, arguing that it shows

Strudwick's distinctive style in its first florescence, when his colours were brighter and compositions less shadowed than at a later stage. The reds and blues of the draperies, the turquoise of the pavement and the lapis lazuli blue of the right-hand column, and the freshness of the landscape, with its drifts of almond blossom, seen through the arcade placed across the width of the composition, are all characteristic of the painter's early career. As George Bernard Shaw wrote in his important 1891 article on Strudwick's art, "in colour these pictures are rich, but quietly pitched and exceedingly harmonious. They are full of subdued but glowing light; and there are no murky shadows or masses of treacly brown and black anywhere." [68]

Bibliography

Kolsteren, Steven. "The Pre-Raphaelite Art of John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937)." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies I: 2 (Fall 1988): 1-16.

Newall, Christopher. Victorian and Edwardian Art. London: Sotheby's (13 December 2005): lot 24, 68-69. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2005/victorian-edwardian-art-l05133/lot.24.html

Shaw, George Bernard. "J. M. Strudwick." The Art Journal LIII (April 1891): 97-101.

Created 25 September 2025