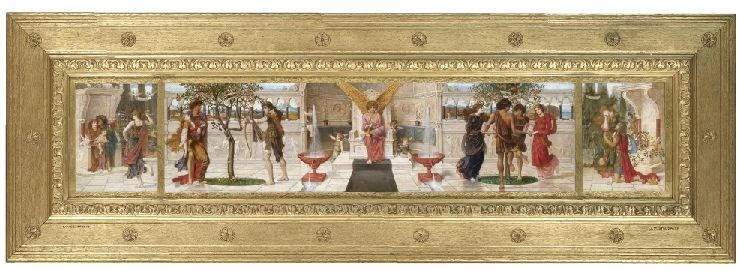

The painting in its original carved gilt frame.

Love's Music, by John Melhuish Strudwick, 1849-1937. 1877. Oil (? tempera) on three panels, contained in the original carved gilt frame; overall 8 ¼ x 45 inches (21 x 114 cm); two panels 6 x 8 inches (15.5 x 20 cm); the central panel 6 x 30 inches (15.5 x 77 cm). Private collection, image courtesy of Sotheby's, London. [Click on all the images on this page to enlarge them.]

Love's Music was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, no. 58, the year the gallery first opened. Exhibiting there was by invitation only, so it is likely Strudwick was recommended to Coutts Lindsay by his mentors Edward Burne-Jones and J.R. Spencer Stanhope. The picture is an astonishing accomplishment for a young artist who until recently had been a studio assistant first to Stanhope and then to Burne-Jones. It exemplifies Strudwick's own individualistic style of painting in its early phase, although the influence of Stanhope, in particular, can still be seen. It was the second of Strudwick's many paintings relating to themes evoking music, the first being Song without Words that he had exhibited at the Royal Academy the year previously; and the first of the broad sweeping canvases for which he later became well known, perhaps influenced by similar works by contemporary artists like Frederic Leighton, William Blake Richmond, or Walter Crane.

The panels without the frame.

Christopher Newall has described the conception behind Love's Music:

The composition of the central panel shows at its centre a stonebuilt apse enclosing a throne upon which is seated the figure of Love, a youth draped in red robes and with gilded wings, and at whose feet are four cupids. He is identified by the word "Amor," carved into the lower panel of his throne. Love plays a horn which suggests the painting's main theme and symbolic gist. On either side of the apse stone colonnades, incorporating relief sculptures, extend across the width of the composition, and through which may be glimpsed a rolling landscape of hills and coast. In front is a paved area, and with fountains playing in red stone basins. At either side are groups of figures, each gathered around fruit trees growing in circular beds, and prompted by the sound of the music to see whether love will bring happiness or tragedy. On the right side, four figures hold hands and form a circle around the tree to engage in a courtly dance, with the two men each raising their right feet in step, while the two women demurely watch their respective suitors. The hopeful message of this episode is supported by a band which rests in the branches of the tree, lettered with the words "Amor est vita" [Love is life]. On the panel's left side, however, a parallel scene unfolds, which warns that all may not end happily: two men who are rivals for the love of one woman confront one another around the tree, with one shooting an arrow which strikes the woman who is the object of both of their desires. She dies in the arms of the other. Here the inscribed message is "Amor est morte" [Love is death]. The two separate lateral panels show scenes which may be regarded as the consequences of the alternatives of contentment or rivalry in love. On one side we see a scene illustrating the motto "Amor est concordia" [Love is harmony], showing a loving man and wife seated together and with their child in a sculpted throne, while a maiden dances to them. On the other side, however, is shown a similar throne but which is here abandoned and already overgrown with brambles, while a desolate woman refuses to be comforted by the figure of a king who kneels before her. The message here is that "Amor est discordia" [Love is discord].

Closer view of each compartment, from the left, up to and including the central figure of Love. The one on the far left illustrates harmony in love, with an affectionate family group watching a dancing maiden. On the next panel, rivalry between suitors has meant that love has led to tragic death. The central figure of Love, at the right here, is at the heart of all.

Closer view of the two contrasting compartments on the right, following the figure of Love, illustrating the different outcomes — harmony and discord — to which love may lead.

This painting was owned initially by the Brighton collector Henry Hill, who became the first of Strudwick's loyal supporters, but it is unknown whether Hill bought it directly from the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition. Captain Hill had made his fortune as a military tailor and outfitter. He went on to own four more paintings by Strudwick, including Love and Time, Peona, Isabella, and Passing Days.

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

Although Strudwick was little known as an artist at the time of his first appearance at the Grosvenor Gallery, Love's Music was, in general, favourably reviewed by the critics. The Academy noticed the influence of early Renaissance art on this work: "Mr. John Melhuish Strudwick exhibits a pretty allegory, Love's Music (58), entirely imitative of the Mediaeval thought and manner. Many artists of our day seem determined that painting shall become, like architecture, a purely retrospective art. Intelligent imitation, however, requires some receptive and appreciative cleverness, and this Mr. Strudwick certainly has" (319). The critic for the Art Journal merely mentioned the painting in passing: "We must likewise commend Spencer Stanhope's Eve Tempted (53) and John M. Strudwick's 'Love's Music' (58), in several compartments" (244). W.M. Rossetti in The Spectator felt this work was an improvement over what Strudwick had exhibited the year previously:

There is a picture beneath this, by Mr. Strudwick, which shows a decided advance upon last year's picture in the Academy. It is called Love's Music, and is a painting in various divisions of the different phases of feeling which love excites. It is a long narrow picture, and its arrangement in general treatment seems to be imitated from an old master, but many of the figures are very graceful, the small cupids near the central figure being especially fanciful and pleasing. [632]

Bibliography

Kolsteren, Steven. "The Pre-Raphaelite Art of John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937)." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies I: 2 (Fall 1988): 1-16.

Newall, Christopher. Victorian and Edwardian Art. London: Sotheby's (July 15, 2008): lot 3, 14-17.

Rossetti, William Michael. "Art. The Grosvenor Gallery." The Spectator L (19 May 1877): 631-32.

"The Grosvenor Gallery.-II." The Architect XVII (19 May 1877): 319-20.

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Art Journal New Series XVI (1877): 244.

Created 25 September 2025