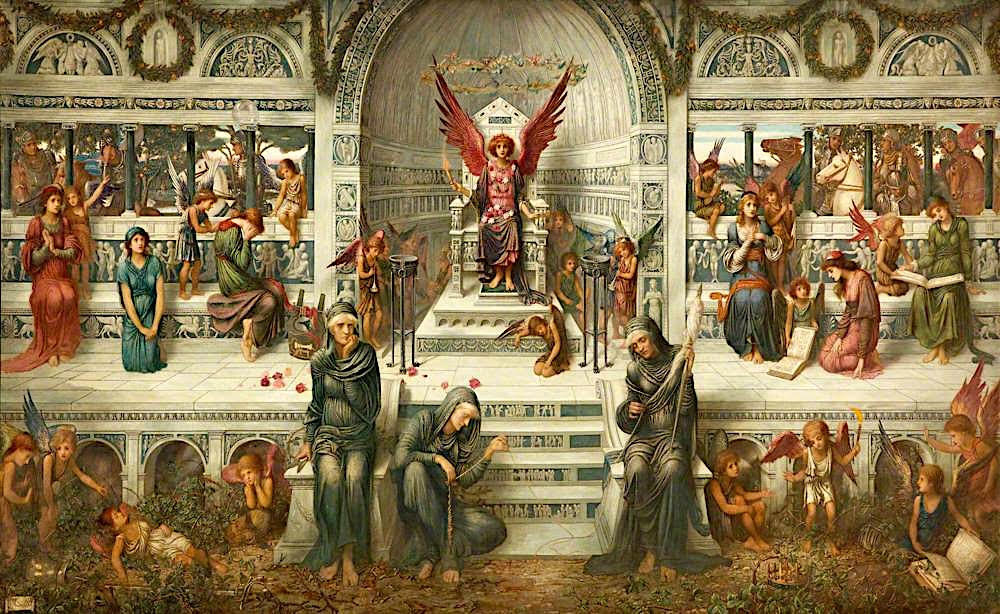

Love's Palace, by John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937). 1891-1893. Oil on canvas; 25 1/2 x 45 ¼ inches (64.7 x 114.9 cm). Collection of Sudley House, Liverpool, accession no. WAG 304. Image courtesy of Sudley House, Museums of Liverpool, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Strudwick exhibited Love's Palace at the New Gallery in 1893, no. 19, and then later at the Brussels International Exhibition in 1897, no. 183. It was the first of the three paintings commissioned directly from the artist by Liverpool collector and wealthy shipping magnate George Holt who was a great admirer of Strudwick's work. He had earlier purchased Strudwick's Circe and Scylla. In a letter of 14 June 1890, Strudwick wrote to Holt about the possible subject that had been agreed upon. It was "to represent 'Love' seated on an ivory throne, and as wonderful a Palace as I can produce - He will be surrounded by 'Loves' and Lovers, by Girls playing musical instruments, by - but I have not yet given this idea shape on paper yet…" (qtd in Morris 441). The painting took three years to complete. Initially the title of the painting was to be The King's Palace, but prior to its exhibition at the New Gallery this was replaced by a couplet by the architect George Frederick Bodley that was published in the exhibition catalogue. Strudwick felt these lines of Bodley's poem expressed well the meaning of his allegory: "Let come what may, for that grim fate decides, Love rules the day, and Love, enthroned abides." Bodley was a friend of many of the second-generation Pre-Raphaelites, particularly Edward Burne-Jones and J.R. Spencer Stanhope, one of whom had likely introduced Strudwick to him. Bodley became not only a friend but also a patron of Strudwick's and in 1894 he commissioned a replica of Strudwick's Golden Strings. The frame of the original version of this subject had another verse by Bodley inscribed on it: "Thy Music, faintly falling, dies away, Thy dear eyes dream that Love will live for aye." (Hall 232). Because none of these epigraphs are from Bodley's published poems, Hall speculates that it is possible Bodley composed them only after Strudwick had painted the pictures (233).

In a letter of 4 May 1893 from Strudwick to George Holt, after the painting had been paid for, Strudwick wrote a detailed description of it:

In the centre Love sits enthroned - Around are a number of winged boys or Amorini, one of whom has fallen asleep at the foot of the throne. At the base of the steps leading to the throne sit the three Fates - Around the feet of Clotho, flowers are growing; while Atropos, who holds the shears, treads upon dead leaves, amongst which are a few ears of corn. On the left of the centre figure as we look at the picture, are three girls; two of whom are watching a bubble as it floats in the air, the bubble has burst for the third girl and she is in grief. A little winged love tries to comfort her, but in vain as yet. On the other side a girl is listening to Love's music; another is learning from Love's book, and another, who is also learning, tries to prevent her winged teacher turning the page, for her lover is whispering to her, and the page is pleasant, too pleasant to be turned she thinks. At the back Knights are riding by. Most of them look into Love's house as they pass; but one, who rides a white horse, keeps his eyes straight in front – Love's joys are not for him - the Knights on the other side are in grief; except the one who rides on the white horse, and keeps his eyes straight in front - Love's sorrows are not for him. Low down in the front of the picture, winged boys are playing among brambles, amidst which live the King's crown, knights' armour, and wise men's books. One of the winged boys sleeps, and his fellows wonder "will he wake again, or is he dead?" (qtd. in Morris 441-42).

Steven Kolsteren points out that "The Fates and Love seem to be unaware of each other's presence, and even of their own surroundings…. In Love's Palace, the lovers are separated and Love rules over sad people conscious of their mortality; he himself is isolated and unable to withhold Time and Fate, symbolized by the three Fates" (2).

Kolsteren thinks this painting may have initially been inspired by Philip Bourke Marston's sonnet "Love's Lost Pleasure-House" which was published posthumously in A Last Harvest in 1891, the same year that Strudwick started this picture. Kolsteren also notes the obvious influence of Pre-Raphaelitism: "Stylistically, the painting exhibits an interesting mixture of the earliest styles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as well as with Burne-Jones, and, in the figures of Stanhope. Besides constricted depths, detailed rendering of objects, and harsh colours, standard Pre-Raphaelitism appears in a quest for something essential, even supernatural: a Romantic mood of escapism, stressed by silence and seclusion, as well as the use of poetical themes. Combining the Pre-Raphaelitism of Holman Hunt, and Rossetti, the modest painter Strudwick was highly sensitive to literature, decoration and colours, and serious and even more rmoralistic in his allegories of life, which led him to dreamland" (2). The background of the knights riding by is very reminiscent of those seen in Edward Burne-Jones's Laus Veneris, which Strudwick would have been very familiar with since it was shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1878.

The Sudley House Museum website has also described the painting: "Enthroned in the centre of the composition sits Love. The three Fates are seated by the base of the steps. On either side of these figures are several young women; some watch a bubble floating away - a symbol of both vanity and hope - and one cries in vain, while the others listen to sweet music and read about love. Behind them are knights on horseback, those on the left symbolising the sorrow of love and on the right, its joy."

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

When the painting was shown at the New Gallery in 1893 only F.G. Stephens in The Athenaeum reviewed it at length although he found it over-laboured and lacking a coherent design in its composition:

There is usually something confused and laboured about the work of Mr. J. M. Strudwick, who, in No. 19, has attempted an apotheosis of Love. The scene is a kind of hall of marble, richly sculptured and painted, while in an open arcade of the background a company of young knights and others are seen riding without. A number of pretty figures of damsels and amorini, which are left quite isolated and are not brought into any relation to one another, are delineated in a manner which reminds of a late sixteenth century illumination of a decaying school. The design cannot be said to be confused, because no composition is discoverable in it; there is no systemized scheme of coloration, tone, or chiaroscuro. Love, a nondescript, splendidly attired and winged, is enthroned under a sort of alcove and upon a platform which is approached by steps in the foreground. Mr. Strudwick has toiled on this curious anachronism and over-laboured rather than firm and really finished style. [576]

A critic for The Artist found Strudwick's Triumph of Love (19) charming as he did Claudius Harper's Dedication but concluded "neither artist draws well enough to fully justify his position on the line" (183).

Bibliography

Hall, Michael. George Frederick Bodley and the Later Gothic Revival in Britain and America. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014. 232-33.

Kolsteren, Steven. "The Pre-Raphaelite Art of John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937)." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies I:2 (Fall 1988): 1-3, no. 21.

Love's Palace. Art UK. Web. 1 October 2025.

Love's Palace. Liverpool Museums. Web. 1 October 2025.

Morris, Edward. Victorian & Edwardian Paintings in the Walker Art Gallery & at Sudley House. London: HMSO Publications, 1996. 441-43.

Stephens, Frederick George. "Fine Arts. The New Gallery." The Athenaeum No. 3419 (May 6, 1893): 576-78.

"The New Gallery." The Artist XIV (1 June 1893): 183-84.

Created 1 October 2025