This unusual book is the result, its author says, of "an all-consuming obsession" (viii) and the zeal that drives it is indeed hinted at in the injudicious choice of adjective in its subtitle "The True Legacy of Elizabeth Eleanor Rossetti." It could equally well be called "Everything you ever wanted to know about Elizabeth Siddal – and then some." It joins the eclectic list of publications devoted to this atypical figure in the history of Victorian art, who in recent years has attracted a variety of champions keen to prove that she is worthy of a degree and kind of attention of which she has been cheated – as the final pages declare, "Elizabeth's own voice has been silenced. It is time for change. This book is just the beginning of the revolution" (189).

Youde, an alumna of the University of York's distinguished art history department, divides her territory into three parts, "Exploding the Myths," "Exploring the Art" and "Exposing the Legacy." She takes the present-day habit of sub-titles and sub-sections to an extreme, with each of these three parts broken down into chapters – eleven in total – which are themselves sub-divided into several parts each with its own heading; in some cases these are merely one page in length.

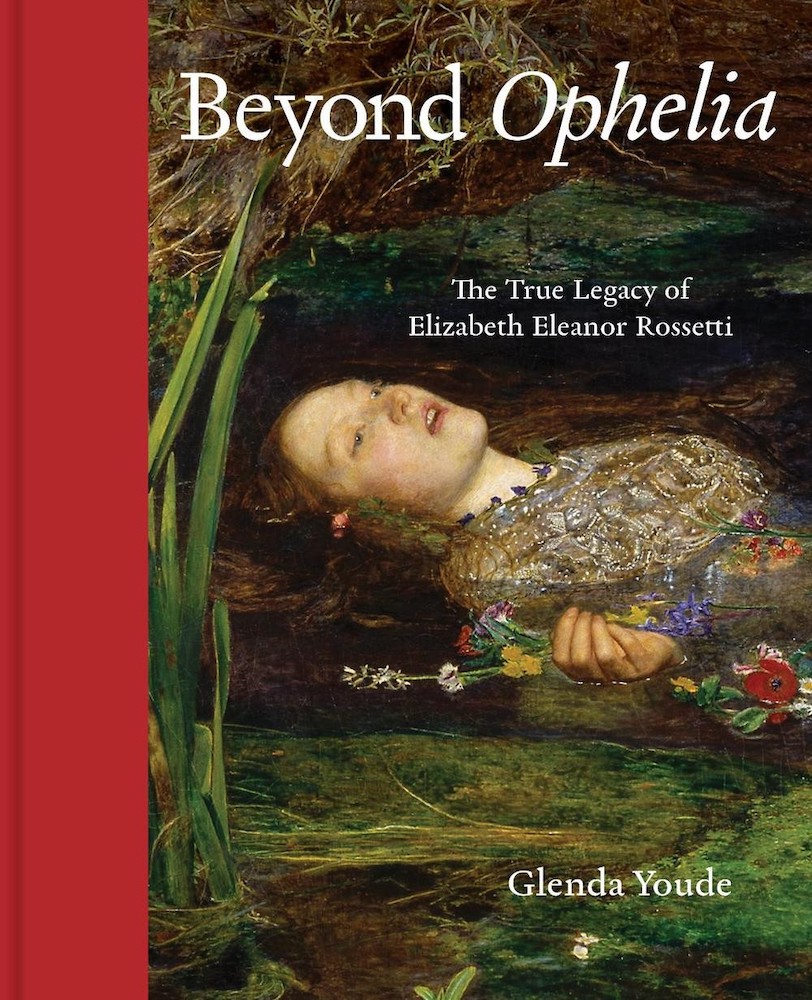

Elizabeth Siddal/Rossetti has, of course, been remembered as "the face of Pre-Raphaelitism," which is where Youde begins: with the best-known instance of that role, Millais' masterpiece Ophelia (1851-52, Tate). The fame that her protagonist has from this work is not the fame that Youde wishes for her: because of her role as model herein, "Elizabeth's notable achievements as an artist and poet have been virtually ignored", she complains (3). Youde moves through the publications (written and visual) that have been inspired by this painting, concentrating on how they have pictured Siddal/Rossetti. She then turns from her heroine as model to Siddal/Rossetti as artist, charting the visibility of her own artwork from the 1850s to the present.

Right: Ophelia, by John Everett Millais, modelled by Siddal. 1851-52. Left: Lizzie Siddal, drawn by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, c. 1854 [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Part 2 homes in on this aspect of the matter, attending at length to a primary source which has been little studied up to now, a set of photographs of Siddal/Rossetti's work that was made to D.G. Rossetti's command. It resides now, at least partially, in the form of glass-plate negatives in the Ashmolean Museum. Youde calculates that her protagonist created upwards of 100 drawings and watercolours, of which the Ashmolean's collection of negatives numbers sixty-one. Herein lie many individually compelling pieces of evidence, such as the photograph of a now unknown watercolour illustrating Wordsworth's poem "We are Seven" and variations on the well-known motifs in Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott." DGR's aim, it seems, was to compile a portfolio of his late wife's drawings for presentation to a select few who had loved and admired her, while preserving a record of the creativity which he had nurtured in this uniquely important person in his life. Ruskin's role in supporting and promoting Siddal/Rossetti's talent came into force from 1855, and Youde shows that with the additional encouragement of Ford Madox Brown, Siddal/Rossetti became an industrious producer of designs based on the Pre-Raphaelite circle's shared enthusiasms – medieval ballads, Shakespeare, Tennyson, Browning and so on. Concurrently, however, her role as DGR's muse only increased, although this factor gives further evidence of her own creative activities in the form of depictions of Siddal/Rossetti by DGR at the easel. One of Youde's primary themes here (repeated throughout the book) is that Siddal/Rossetti and DGR collaborated or, rather, generated a substantial body of collaborative work.

The Quest of the Holy Grail, a watercolour of c. 1855 by Rossetti and Siddal. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Part 3 expands on this contention, which Youde trailed in her contribution to the catalogue for Tate's recent exhibition The Rossettis. She picks apart the closely interwoven activities of Siddal/Rossetti and DGR as the fomer modelled for pictorial ideas that became subjects of the latter's work (and thus now identified as fruits of his artistry). She also analyses in detail the themes, both similar and distinct, in Siddal/Rossetti's own drawings. Positing a kind of creative teamwork, then, Youde goes on to assemble a number of instances in which these ideas, which should be attributed to both creators or even solely to Siddal/Rossetti, appeared in the work of associated artists such as Burne-Jones, Holman Hunt, Spencer Stanhope and (Arthur) Hughes.

Youde concludes, "Clearly Elizabeth's work must be seen as an integral part of the Pre-Raphaelite story. Her ideas caused a directional change in the visual development of Pre-Raphaelite art" (191) ... "Elizabeth's true legacy lies hidden in the work of others" (172, repeated verbatim 186).

The doyenne of Siddal/Rossetti scholarship, indeed the person who has done the most to bring this figure into present-day view, is of course Jan Marsh. Her work has covered nearly all this territory thoughtfully and fruitfully from 1985 onwards, continuing until very recently. Originally a biographer, she has presented Siddal/Rossetti's artistry within a vividly understood social context. Others who have made significant contributions to the present-day awareness of Siddal/Rossetti include the magisterial duo of Deborah Cherry and Griselda Pollock (1984) and the industrious, able but often overlooked Debra Mancoff – whose 1992 essay "Is there Substance behind the Shadows? New Works on Elizabeth Siddal," doing much the same job as that attempted here by Youde in a much more condensed form, is notably absent from this book's bibliography.

Clerk Saunders, a watercolour by Siddal. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

To advance on the work of these scholars must be a central aim of this book, and Youde brings to attention two important sources that have been either missing or under-written by her predecessors. The first is a 1972 doctoral thesis by a German author, Eleonore Reichert, a by-product of the crucial flurry of interest in Siddal/Rossetti's own work within London's commercial sector at the end of the 1960s and early 1970s; the second, the aforementioned portfolio of photos compiled by DGR. Her argument concerning the significance of Siddal/Rossetti's drawings and watercolours (the jury may still be out on whether she painted in oil, but the likelihood seems slim) is her other claim to a new development of the subject.

While the material under discussion is undoubtedly fascinating, whether this argument convinces or not may depend on the reader's understanding of mid-century British society and knowledge of Victorian art en large. It isn't clear from the potted biography on the back of the book how extensive her study of Victorian art has been, but Youde's determination to prove her thesis frequently over-eggs the pudding, leading her to wishful thinking, to forced interpretations of the evidence, and to the evasion of objective conclusions in favour of those that suit her project. The canny historian of any subject keeps in view the spectrum on which, according to the available evidence, the story may move from the demonstrably true to the probable to the merely possible, stopping short of the unlikely, never mind the rugged realm of the unbelievable. This reader found a certain leaden-footedness to Youde's explorations, limited reference to contemporary practices and occasional tin ear for social realities, which taken together weighed against the visual evidence mustered.

Youde states: "Elizabeth has left us a valuable legacy" which has been "excluded" from the narrative (191) but she herself quotes DGR as writing in the 1860s of "Lizzie's sketches – many mere scraps, but all interesting" (57), while Marsh calmly observes of Siddal/Rossetti, "In her lifetime, she had virtually no public identity" (1988: 65). "Scraps" and invisibility do not impress posterity, and while it may be true (to use Youde's favoured epithet) that Siddal/Rossetti's creativity deserves more acknowledgement than it has had, some attention to how a career and an ensuing reputation could be made in Victorian Britain would have tempered the evangelism of this examination of Siddal/Rossetti's significance with a greater understanding of how art and artists enter the canon.

Related Material

- A review of Beyond Ophelia: A Celebration of Lizzie Siddal, Artist and Poet (Exhibition at Wightwick Manor, 2018)

- A review of The Rossettis: Radical Romantics (Exhibition at Tate Britain, 2023)

- A review of The Rossettis (Exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, 2023-24)

Bibliography

[Book under review] Youde, Glenda. Beyond Ophelia: The True Legacy of Elizabeth Eleanor Rossetti. Hbk. Lewes, E. Sussex: Unicorn, 2025. £30.00. ISBN 978-1916846777

Jacobi, Carol, and James Finch eds. The Rossettis . London: Tate Publishing, 2023.

Mancoff, Debra N. "Is there Substance behind the Shadows? New Works on Elizabeth Siddal." The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies. n.s. I:1 (Spring 1992): 21-28.

Marsh, Jan. Elizabeth Siddal, her story. London: Pallas Athene, 2023.

_____. "Imagining Elizabeth Siddal." History Workshop. 25 (Spring 1988): 64-82.

Created 9 May 2025