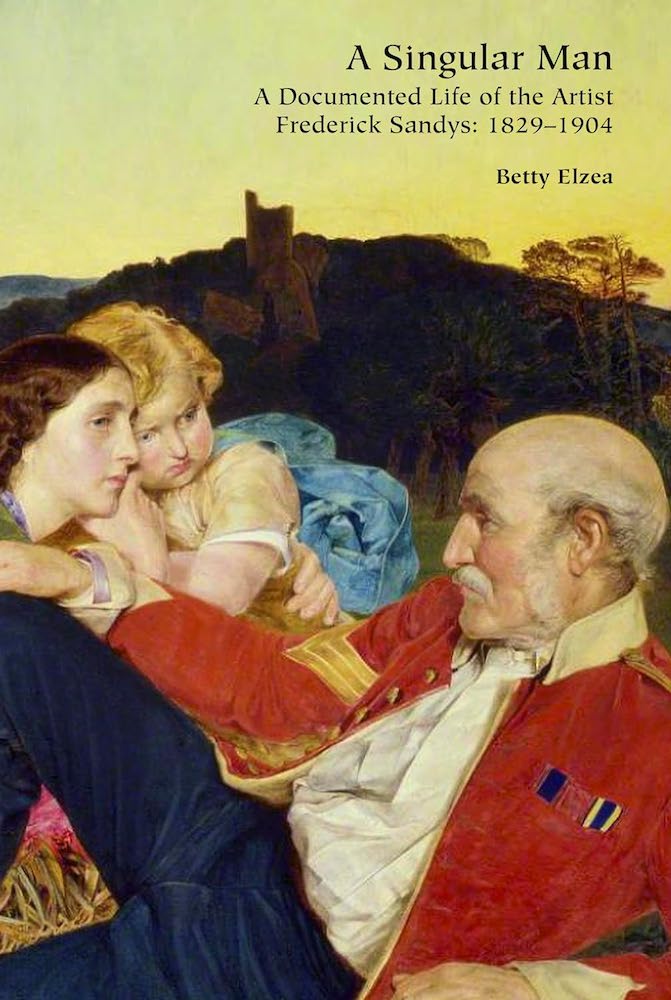

Cover of the book under review.

Betty Elzea's new book is a sequel to the complete catalogue of Frederick Sandys's work compiled by the author and published in 2001. That was a great achievement; here we are given a comprehensive survey of both Sandys's life and the work itself.

Sandys is often viewed as a second division artist who worked on the outskirts of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, but was an associate of Dante Rossetti and an outstanding draughtsman. Born in Norwich, he spent his early years in that city and by the age of nineteen was contributing designs of archaeological antiquities for Rev James Bulwer’s enormous publication, Norfolk Collection, which he formed to augment Francis Blomefield’s Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk published posthumously between 1805 and 1810. The young Sandys provided over two hundred meticulous designs for it between 1845 to 1858.

Sandys studied at the new Norwich School of Design, which was among the earliest of the government art schools founded to provide training in art and design. He was one of the first students to enter this institution and benefitted from the expertise of the first headmaster, William Stewart (1823-1906). In 1846 he won a silver medal at the Society of Arts in London for a portrait drawing. In 1847 he won another medal, this time for an oil painting entitled Wild Ducks from Nature.

Self-Portrait in a Broad-Brimmed Hat, c. 1848.

Sandys continued working in Norwich, and began to enjoy patronage especially for his portrait drawings of local worthies. By the 1850s he was busy with commissions both in Norfolk and London; his London debut was for two oils done in his medieval Pre-Raphaelite style, Mary Magdalen (c.1859) and Queen Eleanor (1858), which were shown at the British Institution gallery in 1860. He associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, notably William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and Arthur Hughes, and began to receive contacts via Rossetti who introduced him to the fashionable actress Ruth Herbert; he drew a portrait of her and her friends. Such contacts helped him to become in demand from those involved in the theatrical world in the capital but he was also to spend much of his time in Norfolk where he met a local patron, William Houghton Clabburn, who employed him to provide portrait drawings of his father, his wife and his mother.

Queen Eleanor, 1858.

Elzea writes effectively of Sandys’s life, and all of this information is backed up with clear and comprehensive discussions of sitters as well as details about his patrons. Elzea has been working on Sandys since 1973 and this book is the result of meticulous research using original letters, documents and diaries. In fact the amount of detail included means that all the work of the artist is presented to the reader in extensive and succinct prose – erudite but always readable.

The 1860s proved a period of great activity for Sandys and is described as the most “fruitful” of his life. The demand for his portraits was increasing. He painted a portrait of Mrs Stephen Lewis which turned out to be one of his finest. Set in an elaborately staged interior it came close to the work of Hans Holbein who was greatly admired by Sandys. Then, in 1863, he showed his portrait of Mrs Susanna Rose at the Royal Academy, and this exhibit was to mark his true entry into the London art world. It was widely praised; Robert Ross, evaluating these two pictures in the Dictionary of National Biography, stated that they were “among the great achievements of English painting.”

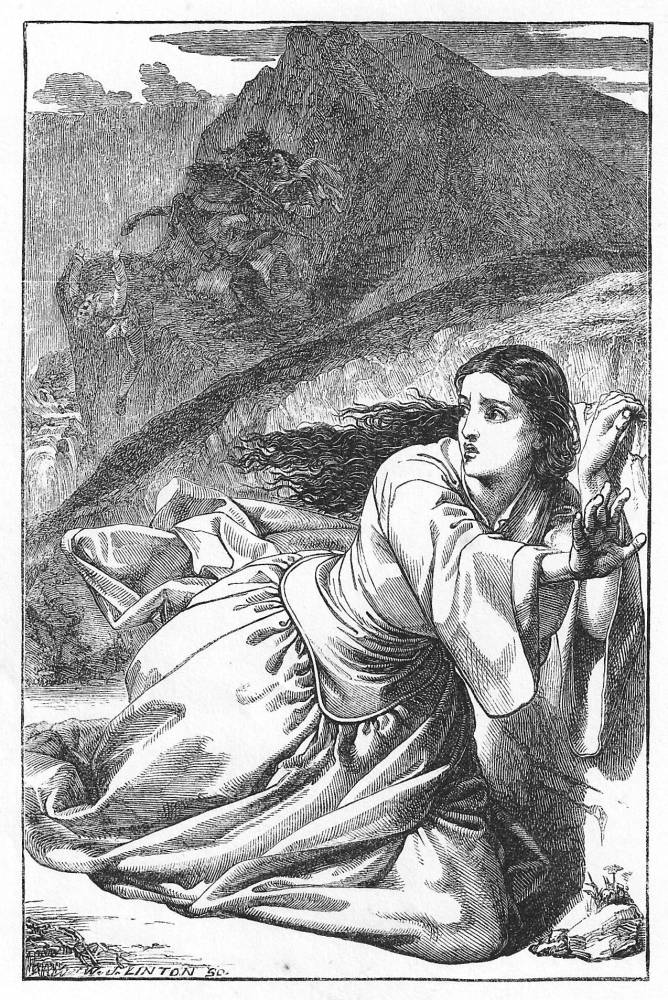

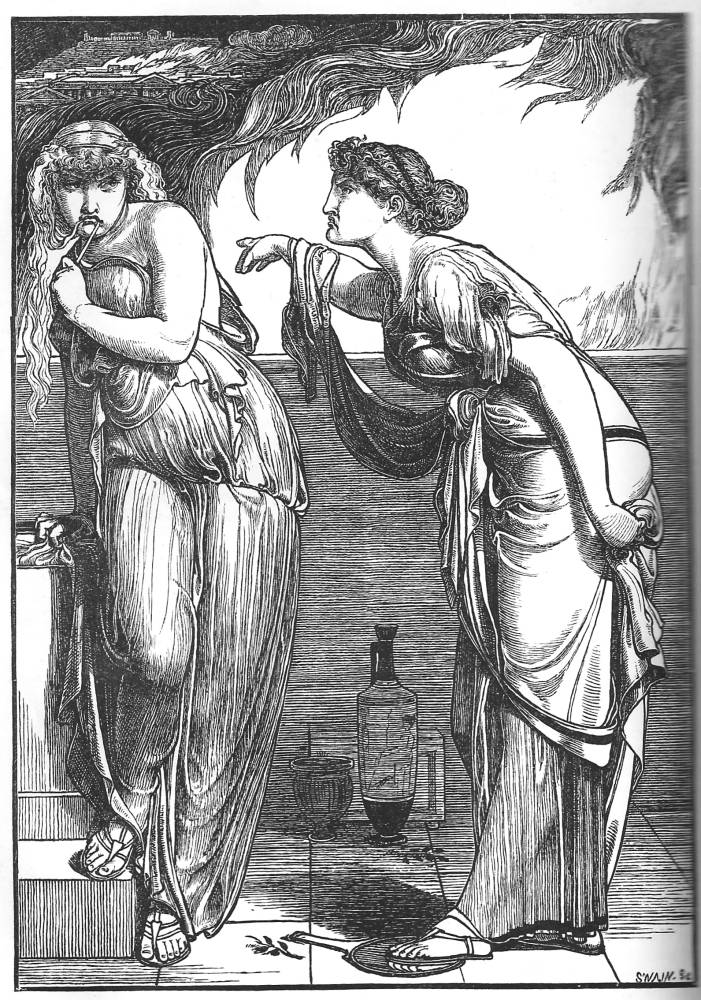

In the field of work for books and periodicals Sandys produced just twenty-five wood-engravings, all of which are distinguished. His first, The Legend of the Portent, appeared in the first issue of the Cornhill Magazine of May 1860. It illustrated "The Portent," a short story by George Macdonald. Further commissions came from the editors of the rival periodical, Once a Week, and two designs in 1861 were Yet once more upon the organ play… to illustrate a text from "The German of Uhland” and The Sailor’s Bride which accompanied a poem by Marian James. Indeed, Sandys was to provide in all twelve designs between 1861 and 1866 for Once a Week, which became the home of more of his work than any other periodical.

Three of Sandys's illustrations for periodicals, from left to right: (a) The Portent for The Cornhill (1860). (b) The Three Statues of Aegina (1861) for Once a Week. (c) Helen and Cassandra for The Cornhill (1866).

For some critics, his illustrations are among his greatest artistic achievements; nevertheless, during this period Sandys continued to paint. A number of these new works portrayed the gipsy Keomi Gray, who was strikingly beautiful, become his mistress, and bore him several children. Most of these pictures were dramatic, including Judith and Holofernes, 1863-64, and Medea, 1866. Rossetti and Sandys became estranged in 1869 because Rossetti accused Sandys of plagiarising his work by working on similar themes. However, Elzea points out that their styles were very different. The rift was later repaired.

1875 was a good year for Sandys and he received several commissions for his magnificent chalk portrait drawings. However, by 1876 he was in financial difficulties and was declared bankrupt in July of this year. The details of the reasons for this state of affairs are explained clearly and the author reveals at length the views of his creditors. Yet Sandys continued to work on portraits despite these problems. He also had family responsibilities; by 1879 he had some seven children by his wife Mary, and four more by Keomi.

Unfortunately he was served with another bankruptcy notice in 1880, while working on a portrait drawing of the Flower family. Cyril Flower was one of his debtors, but he worked out a method to help Sandys out by paying him £12 a week; this small sum enabled him to keep his head above the waterline. We learn of more financial difficulties during this decade, for Sandys was constantly having to borrow in order to meet his debts. However, his numerous commissions enabled him to somehow keep his debtors at bay. Again, all of this information is dealt with in great and illuminating detail.

An Ideal Head, a drawing in black,

white and red chalks of c. 1880.

How Sandys managed to produce so much work is really incredible, bearing in mind his financial worries and his family concerns. In 1884, for instance, he completed a fine chalk drawing of Tennyson, although the sitter proved difficult and Sandys was constantly irritated. He continued to draw his portraits throughout this challenging period.

Towards the end of the book is a fascinating chapter devoted to Sandys’s aesthetic attitudes, techniques and materials. Elzea’s range of material is novel, much of it entirely new, and the author has researched Sandys in a manner that is quite ground-breaking. Indeed, the work is completed in such detail and in so much depth that it demands no successor. This is a superb life, erudite but accessible, and a scholarly triumph. It is also very well illustrated.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Elzea, Betty. A Singular Man – A Documented Life of the Artist Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. Norwich: Unicorn Press, 2023. £30.00. ISBN 978-1838395391.

Created 15 April 2024