For details of the exhibition's associated publication, also titled Women of Influence: The Pattle Sisters (edited by Emily Burns), please see the bibliography. Apart from the installation shots, and the last photograph in the grounds of Little Holland House, the images featured below can be found elsewhere on our own website, often by kind permission of the Watts Gallery. Click on them for more information, and to see larger versions of them. — Jacqueline Banerjee

I first encountered the Pattle sisters almost a decade ago while researching the Victorian artist, George Frederic Watts, trying to understand how his networks helped secure his international reputation. Many Victorianists who know the seminal work of Caroline Dakers and Wilfred [or Wilfrid] Blunt will be familiar with the story of how this budding painter plagued by illness came into the care of Sara Prinsep (née Pattle) at Kensington’s Little Holland House in the 1850s. There she created a legendary salon frequented by many of the century’s leading figures, including Lord Alfred Tennyson, William Gladstone and Sir John Herschel, and Watts soon became her artist‑in‑residence. Sara Prinsep famously remarked that "he came to stay three days; he stayed thirty years" (Watts 128). In practice, he lived with the family for twenty‑one years, painting portraits of their visitors in what became known as his Hall of Fame series and developing the allegorical subjects that would establish him as a distinctive social commentator in an age of accelerating industrialisation, mobility and empire.

At first, it seemed astonishing that so much activity could be traced back to the ingenuity and communicative powers of one woman. It very quickly became clear that Sara Prinsep belonged to a remarkable constellation of seven Pattle sisters who, collectively, exerted a quiet but distinctively feminine influence on nineteenth‑century society, shaping British art and culture in ways that still reverberate today. The Pattles were Adeline, Julia Margaret, Sara, Maria "Mia," Louisa, Virginia and Sophia. I found myself wondering why they had never been placed at the centre of an exhibition before.

Fast‑forward to 2022, and Emily Burns (then curator at Watts Gallery) raised precisely this question with me in a committee meeting. After some discussion, I was invited to join the project as co-curator with Corinna Henderson joining me in 2024.

In curating Women of Influence: The Pattle Sisters at Watts Gallery, the aim was never to simply present a group of historical figures. I wanted to foreground the feminist, sisterly and decolonial perspectives which shaped the Pattles’ lives and legacies. My intention was to re‑animate their presence: to restage their salon, to let their conversations echo once more through the halls of Victorian art, and to reclaim their influence as a guiding force rather than simply a sidenote in accounts of Victorian men.

G.F. Watts’s rare double portrait, The Sisters: Sophia Dalrymple

and Sara Prinsep (1852-53).

That is why our exhibition opens in the historic galleries with Watts’s rare double portrait called, The Sisters: Sophia Dalrymple and Sara Prinsep (1852-53). Painted on the balcony of Holland House, this portrait introduces two of the seven sisters upon their entry into London society as Anglo-Indian women complete with Kashmiri shawl, rakhis (sacred bracelets tied by siblings), and large almond shaped eyes.

Operating at a time when women’s opportunities were limited to the domestic sphere, the Pattles benefited from considerable privilege. They were not only born into an affluent East India Company family in Bengal. They also received a French education and experienced elements of the European "grand tour" at a time when most women had access to far fewer opportunities. Their father, James Pattle, was an English civil servant who was known for being a drunk, argumentative gambler in Calcutta (today’s Kolkata). Their mother, Adéline Maria Pattle (née de L’Étang), came from a French colonial family with ties to the court of Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI. In fact, we believe that her great-great-great-grandmother was a Bengali Hindu from Chandernagor who was baptised Marie Monica, or Monique, having converted to Christianity and marrying a French officer in Pondicherry on 2 July 1703. Thus, the Pattle sisters held a multicultural heritage with English, French, Bengali and Swiss ancestry. This enabled them to take up leading roles within colonial society through marriage. For example, Sara wed Henry Thoby Prinsep who became Chief Secretary to the Indian Government and an expert on ancient Indian and Persian texts. Julia Margaret married Charles Hay Cameron, a law commissioner, and became the highest ranked woman within Calcuttan society assuming duties reserved for the Vicereine seeing as Governor General Henry Hardinge was unmarried.

We see these multicultural, colonial links painted onto the canvas in Watts’s The Sisters for both Sophia (left) and Sara (right) have fair complexions, auburn hair and large "Pattle eyes" or "Pondicherry eyes," as they became commonly known. This portrait was not simply a likeness of the Pattles, though. What we hope visitors to the exhibition, and readers of its accompanying publication, come away with is a real sense of the co-creation process which developed between artists and models – with the Pattles serving as more than just inspiration, but as patrons and influencers of contemporary art from the period.

The Little Holland House Album (1859) on show at the exhibition.

This narrative of influence continues with one of my favourite objects from the entire exhibition – our star item, the Little Holland House Album (1859), lovingly prepared by Edward Burne-Jones and gifted to Sophia Pattle (later Dalrymple) in gratitude of their time spent together in Sara Prinsep’s home. This was in the year of the " great stink" on account of sewage impacting the smell from the River Thames. Suffering from overwork and nervous exhaustion, Burne-Jones came into Sara’s care in much the same fashion as Watts had ten years prior. Considered "the greatest genius of the age" and yet "shy, delicate and without any visible signs of female support," Burne-Jones entered the Prinsep household to convalesce (Burne-Jones 8). From this time, he produced an album rich in medieval-inspired illustrations, poems and stories centred around the theme of courtly love with the young artist sketching a dedication to Sophia onto the final page alongside notes of music and her insignia. Thus, whereas Sara exerted a motherly influence and patronage, Sophia became something more romantic. The album, therefore, is both synonymous of the Pattles’ influence over Burne-Jones and the formation of his early Pre-Raphaelitism. Lent from a private collector, this album has been rarely exhibited so we are very lucky to be able to display it.

Humanity in the Lap of Earth (1851–52).

Watts’s fresco Humanity in the Lap of Earth (1851–52), on loan from Leighton House, offers a vivid glimpse into the collaborative, at times symbiotic creative exchange that flourished between Watts and the Pattle sisters. Commissioned by the Prinseps and originally painted directly onto a wall at Little Holland House, the fresco formed part of a wider scheme of allegorical works which frequently featured the Pattles. These works mark Watts’s earliest foray into Symbolist ideas that would culminate in his internationally acclaimed House of Life series, painted from the 1880s until his death in 1904. Yet the fresco also carries a poignant legacy that extends beyond its artistic significance. When Little Holland House was slated for demolition in 1875 to make way for Melbury Road, Watts’s biographer, Emilie Barrington, painstakingly rescued this fragment. Today, it is believed to be one of only two surviving pieces of the house’s once richly painted interiors, serving as a rare, tangible remnant of the creative environment which shaped both the cultural life of the Pattle–Prinsep circle and Watts’s artistic career.

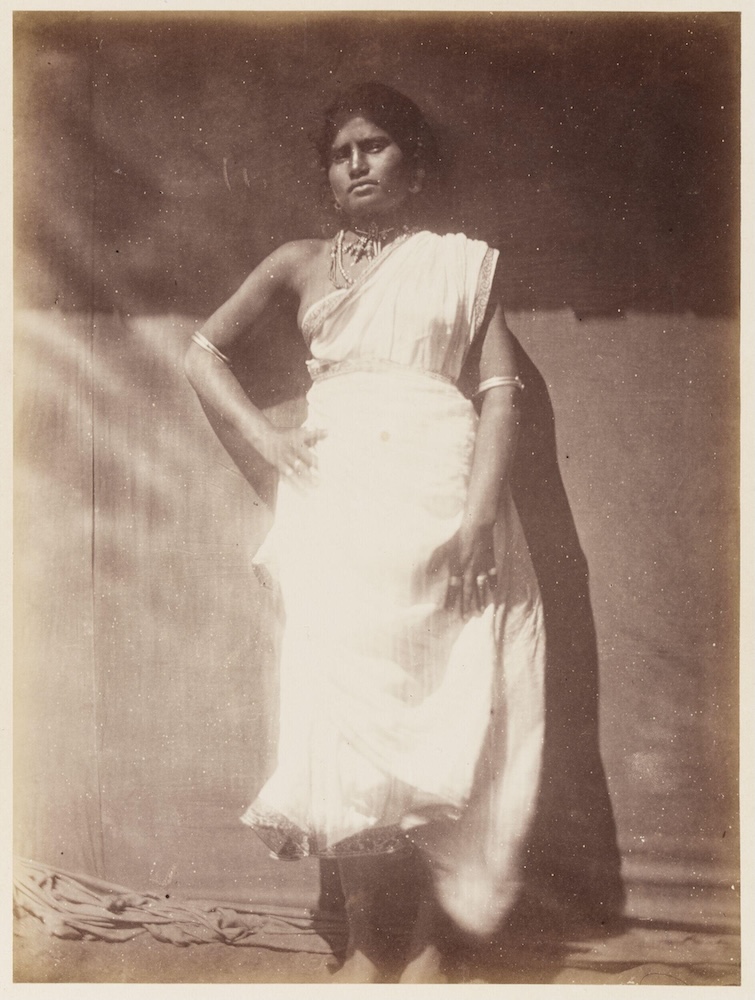

In conversation with male contemporaries such as Watts, Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose works are featured in the exhibition, I wanted to reframe Julia Margaret Cameron’s photography (née Pattle) by placing it within the vibrant context of her sisters and their wider creative network. The penultimate section of the exhibition traces these influences on Cameron’s practice, from her letters to mentors such as Watts and Herschel, through to her intimate family portraits – including the strikingly aesthetic images of Virginia Pattle and Mia’s daughter, Julia Jackson – and culminating in her evocative photographs taken later in life in British Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). Drawing inspiration from the latest scholarship in the field of Cameron studies, artworks such as Young Woman (c.1875-79, a facsimile photograph) are exhibited in ways which challenge the contention that the Ceylon period was merely for documentary purposes. Instead, we link Cameron’s practice to her study and work in England both at Little Holland House and Freshwater on the Isle of Wight.

Left: Section of the exhibition on Julia Margaret Cameron. Right: One of Cameron's photographs of Ceylonese women at the exhibition.

The exhibition culminates by tracing the Pattle sisters’ enduring legacy in the modernist innovations of the Bloomsbury Group in the twentieth century. Returning to a photographic portrait of Mia Pattle, most likely taken by Oscar Gustave Rejlander and displayed in the showcase gallery, we can see how the Pattle sisters’ distinctive confidence, bohemian spirit, and aesthetic sensibility echoed in the creative lives of Mia’s granddaughters, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Their own sisterly dynamism, feminist expression, and artistic experimentation can be understood as a direct continuation and rejection of the cultural and creative ethos cultivated by the Pattles.

Gathering in front of Little Holland House, date and photographer unknown, in the collection of the Watts Gallery Trust. Watts himself can be seen sitting on the far right.

What I hope emerges from this object-led tale of sisterhood is that the Pattles were not just a part of cultural history, they were drivers of it. Long before hit tv-shows like Bridgerton and The Buccaneers celebrated womanhood and sisterhood, the Pattles were declared the "diamonds of their season." Long before we spoke about influencers, they were living the role: defining artistic taste, forging powerful networks, challenging fashion, and creating the kind of cultural buzz that defined an era. It is my sincere hope that this exhibition re-establishes their role and influence within Victorian Britain, contributing to the increased recognition of women throughout history whose unique vision and energy have transformed our cultural landscapes as explored in further exhibitions and scholarly research into the subject.

Links to Related Material

- G.F. Watts's portrait of Sophia on her own (1851-53)

- [Ceylonese Woman] (another of Julia Cameron's portraits in Ceylon)

- Little Holland House

Bibliography

Burne-Jones, Edward Coley. The Little Holland House Album. North Berwick: Dalrymple Press, 1981.

Burns, Emily, ed. Women of Influence: The Pattle Sisters, with chapters by leading experts including Dr Caroline Dakers, William Dalrymple, Dr Marion Dell, Dr Gursimran Oberoi herself, and Jeff Rosen. Compton: Watts Gallery Trust, 2025. Available here.

Watts, Mary Seton. George Frederic Watts. Part 1: The Annals of an Artist’s Life. London: Macmillan, 1912.

Created 14 December 2025