Illustrated from our own website, although the same illustrations may be found, among many others, in the book itself. Please click on the images to get more information about them, and to see larger versions of them.

Victorian Artists and Their World, 1844-1861 has a stellar cast of contributors and a fine variety of illustrations. Moreover, the authors of these essays had access to the diaries and letters of a small circle of artists well deserving of greater recognition: Joanna Mary Boyce Wells (1831-1861), her brother George Price Boyce (1826-1897), and her husband Henry Tanworth Wells (1828-1903). The Boyce siblings were the children of George John Boyce, a well-heeled and enlightened businessman who encouraged their artistic inclinations, taking them on a sketching trip to Betws-y-Coed in mid-Wales, and later conducting Joanna on a visit to the Paris art galleries. The trip to Wales was in 1849, and in this year too William Frith came to their home to be shown their early work. It was a promising start. By the time Joanna married Wells, who was less fortunate in his background but had nevertheless embarked on his own artistic path, the three young artists had formed a small but intimately linked artistic community.

Hungry for inspiration, they had already begun travelling widely at home and in Europe, much as earlier artists had taken the obligatory Grand Tour. Like Betws-y-Coed, where the Boyces first met Wells), the places they chose were tried and tested artists' destinations, and included not only Paris, but Rome and Venice. The newly-wed Joanna and Henry Wells spent their honeymoon in Naples in 1857, and George Boyce would later travel as far as Cairo, a popular draw for artists with Orientalist interests. In the first essay here, Sue Bradbury's map and research into their correspondence bring their experiences to life and provide illuminating contexts for paintings as different as Wells's A Farmhouse Kitchen in Betws-y-Coed (1849), and George Boyce's The North Side of St Mark's, Venice (1854), while also affording rich material for those interested in Victorian travel literature.

Yet these travels were only part of the trio's artistic training. The biggest surprise in the next essay, by Matthew Potter, is the variety of ways into the profession. For the young Boyces, contact with David Cox in Wales was only one, if significant, step on a colourfully varied journey. Joanna, for example, took classes at several different schools of painting and drawing, including Leigh's Academy, where she and Wells both attended classes in the early 1850s. Wells had already served an apprenticeship as a lithographic draughtsman, and George Boyce derived much of his skill in draughtsmanship (evident from several studies reproduced here) in a different way — from his architectural training with some major architects of the day, including William Burges. Particularly informative here is the discussion of the influential Thomas Couture, in whose atelier in Paris both Édouard Manet and Mary Cassatt studied: Joanna attended classes with Couture for about three months, longer than was once thought, realising from this experience that drawing nudes could be, and indeed, should be, "as unconstrained for women as it was for men" (81) — although this was not an opinion she felt able to share with her peers at home. Still, Potter shows that she resisted Couture's influence in certain ways. Like her brother and her husband, she made the most of the various training opportunities at their disposal, but developed her own individual style.

The Oxford Arms, Warwick Lane, City of London by George Price Boyce, c. 1868, showing his interest in architecture, and his skill in depicting it.

Alicia Hughes writes next on the art market, and the need to penetrate it, an aspect of the profession that helps to explain the way artists banded together in "schools," "cliques" or exhibiting societies for support and visibility; and Joyce H. Townsend looks at the various materials available, such as the greater range of pigments now being sold, a practical aspect of the profession that had the important effects of boosting the appearance and status of watercolours, and making a fundamental impact on any work — discussing Joanna Boyce later, Herrington recalls a critic noting in 1935 that she went beyond Pre-Raphaelitism in the "warm, deep colouring" and "true feeling for pigment" of her paintings (193). Modern scientific analysis has proved useful in confirming such observations; but less technological skill is required in order to understand how working on ivory and vellum affected Wells's miniatures, much admired at the time and still exquisitely fresh now. This is another subject picked up again later, when it is examined at length by Herrington, Louise Cooling, and Hughes herself, with contributions from Sue Bradbury and Mark Pomeroy, in the book's final essay. It is perfectly true to conclude, as Hughes does in this earlier chapter, that "A study of their painting processes encapsulates a study of their age" (125).

Princess Mary of Cambridge (1835-1897), later Duchess of Teck (1853),

a miniature by Henry Tanworth Wells.

By now we are very much aware of the widening of the focus from these three artists to encompass the many inter-related developments in their artistic world. Along with Pre-Raphaelitism, for instance, consideration is given to the rise of landscape painting and the continued popularity of history painting, with a special interest in the medieval period. In more practical terms, the contributors note the narrowing of the gap between high art and the fine arts, and advances in many aspects of the artist's life, including those examined by Bradbury, and Potter — art training and materials. Hughes also notes the impact of a new art form, photography, on Wells's particular speciality, portrait-painting. It produced a significant shift in demand: we will learn in more detail later how the tailing off of commissions encouraged him to broaden his scope, and paint larger canvases of more general interest to us today.

One of Boyce's landscapes: The Teme at Ludlow, 1871.

Perhaps most importantly, we see how the status of women artists began to improve — although not without a long struggle. Unsurprisingly, then, at heart of the book are three essays on Joanna Boyce Wells by Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Herrington herself, and Meaghan Clarke. Their emphasis on her is not just from considerations of gender: this artist has already begun to emerge as the most innovative of the three. All three essays now reveal, from different angles, the extent of a talent so sadly lost when she died after giving birth to her third child in 1861. She was not even thirty. All too common a tragedy, this was nevertheless an especially great blow to her profession as well as to her family.

Gerrish Nunn had first drawn drawn attention to Joanna Boyce in her seminal book, Victorian Women Artists (1987). Long her advocate, here she shows how this gifted and dedicated artist stood back from the Society of Female Artists, formed in the very year of her marriage, and fought marginalisation by competing in the mainstream, rather than confining herself, as so many women artists did, to "amateurism and copying" (151). Her aloofness from the SFA may have been down to her husband's influence, Gerrish Nunn acknowledges, and the cost was high, witness her soul-searching and struggles with her duties as a daughter, wife, and young mother: she like other women had to contend with "tangled thoughts about dependence, self-fulfilment, the appropriateness of family to determine women's lives" (161). But the result was memorable work that could be pointed to in exhibition "as proof of this new population of painters" (166). Furthermore, it sold, sometimes even before being exhibited. In this way she became, as Gerrish Nunn demonstrates so effectively, an important voice for her peers.

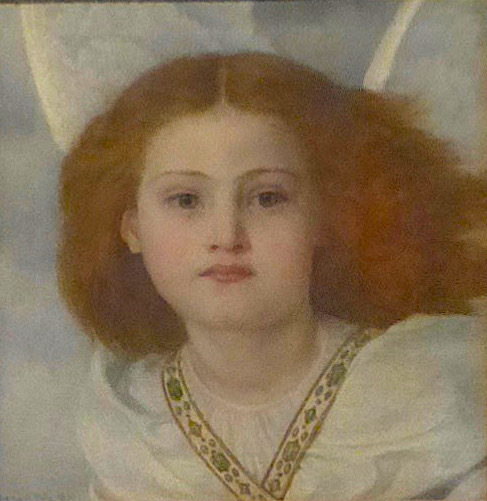

Three paintings by Joanna Boyce Wells. Left to right: (a)Portrait of Sidney Wells (1859). (b) Study of Fanny Eaton (Head of a Mulatto Woman) (1861). (c) Thou Bird of God (1861).

Herrington then provides close analyses of individual works like The Heather Gatherer (admired by G. F. Watts, among others), showing not just their subtle and intelligent refinement of both Pre-Raphaelitism and early Aestheticism, but their emotional sincerity. The latter is naturally very apparent in her paintings of her own children, like the adorable Peep-Bo!, featuring her second child, her daughter Alice. It is left to Meaghan Clarke to look in detail at her "knowledgeable and forthright" art criticism in the Saturday Review (221), an aspect of her work entirely new to this reader, but an important marker of women's emergence into the professional art world.

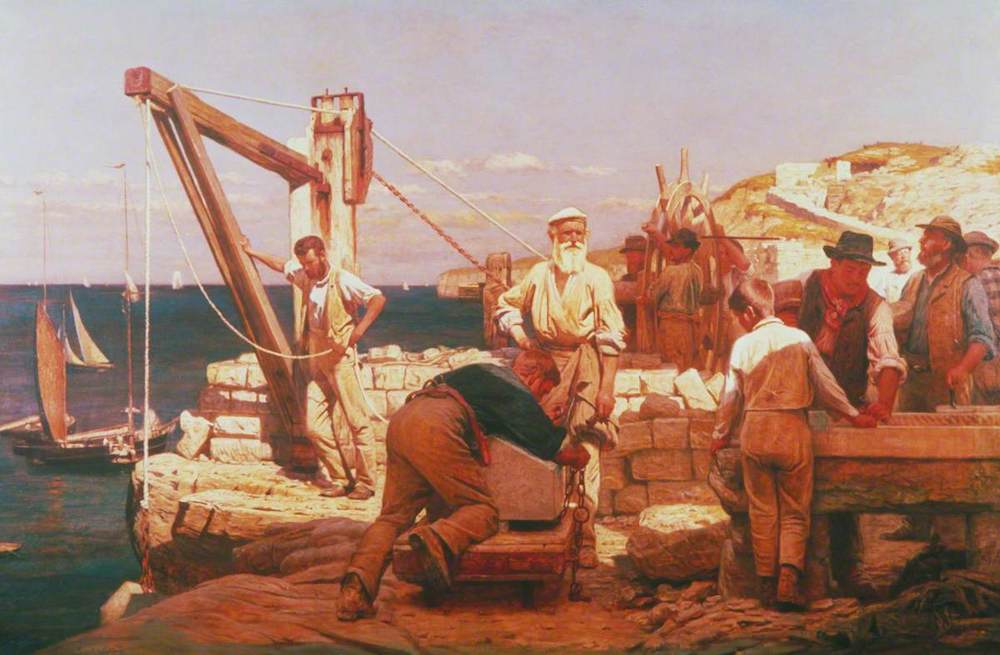

The next three essays, two on George Price Boyce by Christiana Payne and Glenda Youde respectively, and the last on Wells, also cast welcome light on the talents of these under-appreciated artists, with Payne drawing out the uniqueness of the former's vision; Youde giving credit to him as an art collector; and several of the contributors coming together, along with Cooling (curator at Kenwood) and Pomeroy (archivist at the R.A.), to bring specialist knowledge to bear on Wells's portraits and miniatures. There are some wonderful examples of both artists' work here, including George Boyce's "subtle, direct and understated" oil painting, a rare example of his work in oils, Profile Portrait of Ellen Smith (237), and Wells's exquisite miniature (shown earlier in this review), of Princess Mary of Cambridge. It was good to learn that Boyce was a founder member of the SPAB (the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings), and that he acquired and hung Rossetti's Bocca Baciata in pride of place in his Chelsea dining room, where his artistic circle could best appreciate it, thus no doubt contributing to its popularity: there are some fascinating photographs of his collection in situ there. Finally, it was also good to see some of Wells's less familiar works, for instance, his Quarrymen of Purbeck, Dorset (1885). His range was indeed far greater than many will have realised.

Quarrymen of Purbeck, Dorset, 1885, by Henry Tanworth Wells — a less familiar aspect of his work.

Of course, most of the artists the three knew were either Associates of the Royal Academy or Royal Academicians. Its summer exhibition was, indubitably, "the foremost in the country" (166). But Boyce, working almost exclusively in watercolour, was a member of the Royal Watercolour Society, and women, even gifted ones like his sister, while not formally excluded from the RA, were not expected to participate in its procedures. Wells's involvement here therefore adds usefully to the general picture of the profession at this time: he began to exhibit there as early as 1846, and in 1895, as the senior-most Academician, served as its Deputy-President when Leighton was ill. No picture of the art world of this time would be complete without glimpses into its inner workings.

Every essay here is thoroughly researched and repays the closest attention, especially since the earlier part of the century is the less fully researched elsewhere. Topics covered range widely, as we have seen, from the resumption of art travel in Europe after the Napoleonic wars, to the expanding art market onwards. Various schools and groups come under consideration. As Herrington says herself at the beginning, "By virtue of their differing artistic journeys — their contrasting training, the divergent types of paintings they produced, distinct exhibiting practices and additional roles they each played — the Boyce family artists provide a broad and multi-angled view of the mid-nineteenth-century British art world" (15). This engaging collection of essays gives us a window on this whole diverse and dynamic aspect of Victorian culture, and is sure to yield new rewards on every re-reading.

Bibliography

Herrington, Katie J.T., ed. Victorian Artists and Their World, 1844-1861, as Reflected in the Papers of Joanna and George Boyce and Henry Wells. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2024. 312pp. £100.00. ISBN 978 1 78327-259-4.

Created 13 July 2024