he Pre-Raphaelites and their followers relied strongly on narrative sources for paintings. They also created groups of paintings, those discussed here ranging from two to eight, that together convey a narrative. By painting works that not only draw from texts but relate to other paintings, these artists demonstrated with their art a strong desire to make connections. Why did these artists feel such a strong urge to draw connections between literary and visual art, among groups of paintings and occasionally among multiple texts? By creating art with strong connections to texts and other paintings, the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates created art that expanded outside the scope of a single canvas, hence heightening the gravitas, complexity and significance of their works, as well as increasing the demands made upon the viewer. These connections among paintings and texts function in several distinctive ways to achieve this heightened complexity: serial paintings expand upon texts; they manipulate time in ways different from those used in single paintings; and most significantly, they maintain their ties to these texts.

he Pre-Raphaelites and their followers relied strongly on narrative sources for paintings. They also created groups of paintings, those discussed here ranging from two to eight, that together convey a narrative. By painting works that not only draw from texts but relate to other paintings, these artists demonstrated with their art a strong desire to make connections. Why did these artists feel such a strong urge to draw connections between literary and visual art, among groups of paintings and occasionally among multiple texts? By creating art with strong connections to texts and other paintings, the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates created art that expanded outside the scope of a single canvas, hence heightening the gravitas, complexity and significance of their works, as well as increasing the demands made upon the viewer. These connections among paintings and texts function in several distinctive ways to achieve this heightened complexity: serial paintings expand upon texts; they manipulate time in ways different from those used in single paintings; and most significantly, they maintain their ties to these texts.

Paintings expand upon a text by drawing a theme or particular moment from a narrative and both broadening and making more specific an idea in the text. The artists discussed here broaden the scope of a text by sometimes creating moments that are implied rather than actually described in the text; they increase the specificity of a text by depicting details that may not be described in the text, thus expanding the world created together by text and paintings. In many series, the paintings and the texts they use for inspiration complement one another, each providing information not contained in the others, and thereby connecting even more strongly to each other. In addition, the Pre-Raphaelite preoccupation with creating archaeologically accurate and practically believable scenes led them to create complete, evocative visual images that rely not only on description in a text, but also on logical and imaginative extensions of texts, and sometimes on powerful reinventions of the images within a text. By creating a unified world within a series of paintings, artists sometimes created visual narratives, parallel to but expanding upon the associated text.

Paintings painted together as a series contain within the series, from painting to painting, the ideas of temporal progression and implied time in a way that mirrors the structure of a narrative. They manipulate time by requiring a viewer to consider them as a series, as well as in relation to a text. Serial paintings painted years apart or by different artists relate to each other and to a text somewhat differently than planned series. Even if it was not the artist's intention, a painting broadens its potential connections by being linked to a narrative, and hence relates in interesting ways to other paintings drawn from that text. In a slightly different way, paintings drawn from different narratives can complement each other and increase the web of connections the viewer must consider.

Critically, the paintings discussed here do not allow the viewer to sever the connection to the text. This bond was emphasized in different ways: by physically affixing a poem to a painting's frame; by exhibiting a work with a fragment of its textual source or with a brief text as its title; or by drawing from a text that the viewer was expected to know. In the series discussed below, the inclination to expand upon a text in a couple or group of paintings does not at all sever the connection to the textual source. On the contrary, the paintings strongly maintain their connection to the source, requiring a viewer to engage with both the paintings and a text in order to most fully appreciate the visual art. By leaving certain questions unanswered in their paintings, and providing certain details not indicated in their source texts, these artists demanded that their audience consider the strong ties between literary and artistic production. Furthermore, they offered to that audience a more complicated and challenging yet potentially rewarding exploration of narratives in related literature and art.

In one instance considered here, a topic was initially explored together by Sir John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, but then the artists executed their final products with a gap of almost twenty years between them. In another instance, two paintings by Millais seem to relate strongly to one another in a connected narrative, despite their different textual sources. In a third example of this phenomenon, two of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's paintings and an accompanying poem function interdependently. Augustus Egg's series of three paintings, Past and Present, has no textual source, yet a quoted text displayed with the paintings aids in reconstructing his clearly mapped narrative that progresses over the course of the series. Sir Edward Burne-Jones painted several series of paintings, and the one discussed here illustrates the Perseus myth as retold by his close friend, William Morris; yet the liberties Burne-Jones takes and the creativity with which he evokes his own mythical, imagined world make the paintings far more than illustrations. John William Waterhouse painted three different scenes of Alfred Lord Tennyson's "The Lady of Shallot," and although all painted by the same artist, each displays new and different exploration and consideration of his subject.

These artists' use of narrative in serial painting functions in various ways: when two artists depict one narrative, their joint effort draws them closer to each other; the narrative provides connections not only to texts and ideas outside the paintings but also to other paintings; it allows for the creation of different places and times in a strongly linked structure; it also allows different styles and depictions to function dependently and provide a multifaceted view of a story. Thus, one must consider these artists' choices in setting, composition and figures; the moments and details within a story they choose to select and how these relate to each other to heighten or downplay the dramatic tension; their relative attention to the details of the text they use and how effectively they then convey the narrative to the viewer. All these groupings of paintings convey the progression of time and the impact and import of change. Despite the many meanings and symbols crammed into a single painting in almost all of these cases, the images nonetheless provide transient moments that expand enormously by association with other related images.

Different but Connected Responses to Keats' "Isabella: Or the Pot of Basil" in Hunt and Millais

By 1847, William Holman Hunt and Sir John Everett Millais shared a great enthusiasm for John Keats, and they worked together on illustrations for Keats' "Isabella: Or the Pot of Basil." Hunt and Millais used fine brushes rather than pens and considered the works preparatory drawings for etchings. although Rossetti said he would join them in illustrating the poem, he never actually did (Hunt, 103-4 and 142). A tragic tale based on Boccaccio, the poem tells the story of Isabella, who lives with her two greedy brothers, the three sustained by inherited wealth. Isabella and Lorenzo — who works for her brothers — fall in love, to her brothers' horror since they had wanted her to make a profitable, noble marriage. Murder, deceit and heartbreak ensue.

Hunt's drawing contains various groupings of figures, placed in the far and near background, some apparent below an opening in the floor, and some distantly visible through the open door. In the foreground, Lorenzo sits at his desk, distracted by the sound of a hand on the door and knowing that his beloved enters even though she remains momentarily concealed by the door. Beside him, a man who may be one of the brothers bends over, oblivious to the opening door. A dog darts from beside Lorenzo, eager to meet the entering Isabella, who has a similar dog at her side. The moment portrayed illustrates the lines, "He knew whose gentle hand was at the latch / Before the door had given her to his eyes" (III). Despite the multiplicity of figures engaging in different states of work in the sketch, the centrality of Lorenzo and Isabella, situated close to front of the scene, and their pensive expressions help place the focus firmly on them and their as yet secret love.

although both Millais and Hunt would ultimately paint scenes from the poem, Millais began Isabella (1849) soon after they completed the sketches, and Hunt would not paint Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1867) until many years later. Hunt wrote that they each wanted to deal with the position of Lorenzo within the household of the two brothers (Hunt, 142). Millais' painting, completed rapidly in time to be exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, depicts a meal within the brothers' home. Elaborately brocaded wallpaper, tablecloth and garments enrich the scene, as do shimmering velvet fabrics. Lorenzo sits next to Isabella, offering her half an orange from his plate, which she takes cautiously. One of her brothers, evidently now aware of what he views as the undesirable love between Isabella and Lorenzo, has just furiously kicked a dog who falls, his legs lifted from under him, into Isabella's comforting lap. The other brother lifts his glass almost sarcastically to the lovers, his pinky held aloof at an affected angle and his other hand pensively covering his mouth and chin. A falcon with a feather in its mouth perches on the back of this brother's chair, spying the lovers from across the table, and the image of the falcon, though out of context, appears in the poem (III). Both brothers' eyes suggest knowledge of the love, one reacting with a hint of scheming in his eye, the other responding with passionate violence, yet each faintly foreshadowing the course of their actions.

although both Millais and Hunt would ultimately paint scenes from the poem, Millais began Isabella (1849) soon after they completed the sketches, and Hunt would not paint Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1867) until many years later. Hunt wrote that they each wanted to deal with the position of Lorenzo within the household of the two brothers (Hunt, 142). Millais' painting, completed rapidly in time to be exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, depicts a meal within the brothers' home. Elaborately brocaded wallpaper, tablecloth and garments enrich the scene, as do shimmering velvet fabrics. Lorenzo sits next to Isabella, offering her half an orange from his plate, which she takes cautiously. One of her brothers, evidently now aware of what he views as the undesirable love between Isabella and Lorenzo, has just furiously kicked a dog who falls, his legs lifted from under him, into Isabella's comforting lap. The other brother lifts his glass almost sarcastically to the lovers, his pinky held aloof at an affected angle and his other hand pensively covering his mouth and chin. A falcon with a feather in its mouth perches on the back of this brother's chair, spying the lovers from across the table, and the image of the falcon, though out of context, appears in the poem (III). Both brothers' eyes suggest knowledge of the love, one reacting with a hint of scheming in his eye, the other responding with passionate violence, yet each faintly foreshadowing the course of their actions.

Millais does not depict a particular scene from the story. No dogs are mentioned in the poem, yet both Hunt's sketch and Millais' painting contain dogs. Keats does not mention a particular dinner gathering of assembled friends with the brothers and the lovers, although the line "They could not sit at meals but feel how well / It soothed each to be the other by"(I) allows for elaboration on this idea. Millais strays from these lines of text to some extent. Rather than wearing a soothed expression, Lorenzo gazes intensely and anxiously past Isabella, seemingly intensely absorbed in inward reflection on their difficult situation. Isabella does not look soothed either, her deliberate yet hesitant action suggesting her anxiety. although the poem offers various scenes of high romantic passion — the lovers' first kiss (IX), their surreptitious meeting in a bower (XI), the lovers' farewell as Lorenzo rides to his doom (XXVI), and Isabella's vision relating the nature of Lorenzo's death (XXXV) — Millais chooses not to isolate these lovers but to surround them with other figures, including their enemies, in a daily action heightened by tension. Millais portrays the instant of the brothers' angry recognition of Lorenzo and Isabella's love, although the poem does not contain this particular moment. The painting seems to represent the culmination of the "many signs" by which the brothers discerned the love between Lorenzo and Isabella (XXI).

Appropriately, when Hunt used the poem as the source for Isabella and the Pot of Basil two decades later, he chose a scene from later in the poem. Hunt's vertical painting provides an idiosyncratic pendant to Millais' horizontal one. Hunt drastically transforms the atmosphere and the figure of Isabella. No longer located in an early Renaissance room leading onto a loggia, Hunt places Isabella in an exotic, somewhat Eastern setting, with a patterned marble floor and red marble column, a delicately inlaid wooden chest, a frieze over the doorway and an elaborate curtained bed in the background. Millais' Isabella, with her pearly white skin, auburn hair wound tightly by ribbons extending down her back, long pale neck and downcast eyes, has been replaced by an Isabella with unruly jet black hair, tan skin, pronounced eyebrows and dark eyes that look forlornly at nothing.

Hunt's painting more closely follows Keats' details in the poem than does Millais'. Led by the vision to the site of Lorenzo's slaughter, Isabella unearths her beloved's head, cleans it, and places it in a pot over which she plants basil. although Isabella keeps perpetually tearful guard over the pot, she seems to have ceased her crying in Hunt's painting. She does not sit, as Keats says, but rather stands beside the pot, yet Hunt powerfully conveys the image of Isabella with her hair spread over the plant: "Beside her Basil, weeping through her hair"(LIX). A rich green plant seems to sprout out of the veil of hair draped over the top of the pot, and Isabella's arms enfold the shiny vessel, marked by Hunt with small skulls to remind the viewer of its carrion contents. Fraser's Magazine had critiqued Millais' painting in 1849 for its mannerist tendencies (Millais, 70), perhaps referring to the figures' poses. For example one brother's tightly flexed leg appears contrived, and Hunt somewhat awkwardly conveys space; this is particularly evident in the perspective of the table and the transition from the indoor to outdoor area. In contrast, Hunt's figure of Isabella lacks the refined elegance and the stiff poses of Millais' figures. Her appearance does not look idealized, and the room she occupies has convincing depth.

Hunt felt strongly the need for objects to be depicted in practical, archaeologically truthful ways and according to the text or historical event used as the artist's source, as indicated by his scathing comments about Ford Madox Brown's The Body of Harold brought before William the Conqueror:

Brown had adopted a glaringly unreasonable reading of the fact that William went into battle with the bones of the saints round his neck....Instead of painting a reliquary, he had hung femur, tibia, humerus, and other large bones dangling loose on the hero's breast, surely a formidable encumbrance both to riding and fighting. [Hunt, 120]

Yet nothing in "Isabella: Or the Pot of Basil" places it in an Eastern locale as Hunt seems to. although to a certain extent Hunt achieves archaeological constancy and practicability in Isabella and the Pot of Basil, he has at least one bizarre object that breaks with the setting. The richly colored cloth embroidered with Lorenzo's name and Latin words around the border has at least one Christian religious figure with a halo. Thus, this cloth seems incongruous in the Eastern setting Hunt has otherwise conveyed.

Despite their differences in approach and execution, these two paintings complement each other in their depiction of two stages of love: earthly love and love that outlasts the life of one of the lovers. although Hunt's scene takes place before the final turning point in the poem, when Isabella's brothers steal her pot, unwittingly revealing their murderous deed and depriving her of her last remnant of her beloved, the painting nonetheless provides a later moment that balances the early scene depicted in Millais' painting.

Pendants Drawn from Different Narratives: Linking Two Paintings by Millais

Hunt wrote that the members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle found Coventry Patmore's "The Woodsman's Daughter" (text) particularly interesting. Millais painted a scene from this poem that he sent to the Academy in 1852, one year before sending "Ophelia" Hunt, 145 and Monkhouse, 58). although the paintings have different sources — Shakespeare's Ophelia in Hamlet and Patmore's Maud in "The Woodsman's Daughter" — they both contain women who kill themselves by drowning in overgrown streams. Thus, since The Woodsman's Daughter portrays a scene early in the life of Maud, one may view Ophelia not only as a Shakespearian image, but as the fulfillment of Maud's fate and so an accompaniment to The Woodsman's Daughter.

Hunt wrote that the members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle found Coventry Patmore's "The Woodsman's Daughter" (text) particularly interesting. Millais painted a scene from this poem that he sent to the Academy in 1852, one year before sending "Ophelia" Hunt, 145 and Monkhouse, 58). although the paintings have different sources — Shakespeare's Ophelia in Hamlet and Patmore's Maud in "The Woodsman's Daughter" — they both contain women who kill themselves by drowning in overgrown streams. Thus, since The Woodsman's Daughter portrays a scene early in the life of Maud, one may view Ophelia not only as a Shakespearian image, but as the fulfillment of Maud's fate and so an accompaniment to The Woodsman's Daughter.

When exhibited at the Academy, two stanzas of Patmore's poem — though with slightly different wording than in later editions — accompanied the painting (Landow, Victorian Web). Patmore's poem alternates between different periods of time in a fluid way that is harder to achieve in a single painting. Some ways of solving this problem include simultaneous narratives — for example in early Netherlandish paintings such as Hans Memling's Seven Joys of Mary (1480) or in Burne-Jones' Perseus Series as discussed below — and typological symbolism as used in many of Hunt's religious paintings; however, Millais does not use either of these devices in his painting. Beginning with Maud's childhood, Patmore presents a happy, carefree existence for Maud and her father Gerald, each of them willingly laboring, with no hint of their future troubles. The poem's time then shifts into the future briefly to Maud's grief-induced madness, before returning to her childhood and gradually, chronologically explaining how her carefree existence sank into sin, sadness and ultimately death by drowning, all spurred by her relationship with a wealthy squire's son. Initially, this boy simply stares at Maud and her father as they work. Soon the boy gives Maud fruits, though his manner remains cold.

And sometimes, in a sullen tone

He offer'd fruits, and she

Received them always with an air

So unreserved and free,

That shame-faced distance soon became

Familiarity. [Lines 43-48]

Millais' painting powerfully captures the attitudes of the children as described in the poem. Leaning awkwardly against a tree and standing on the outsides of his feet, the well-dressed boy in tights and a tunic stretches out a stiffly straightened arm to Maud, proffering strawberries. His serious, aloof expression and rigid stance contrast strongly with Maud's naturally bent arm, her firmly-planted feet and easy pose, and her comfortable smile that seems to thank him for the fruit and request his friendship with it.

The young friends' class and gender differences lead them to "steal out to enjoy" each other's company and to purposefully conceal the time they spend together. Yet the poem, though glossing over the exact events of Maud's downfall, suggests that her friend seduces and then leaves her, and she comes home to her father broken-hearted and ashamed. Millais' painting does not include many foreshadowing symbols of Maud's demise. However, her idleness in her desire to befriend the boy and her father's turned back, suggesting inattention and perhaps inadequate supervision of his daughter, faintly hint at the negative turn her life will take. Hunt's The Hireling Shepherd (1851) also moralizes on the subject of idleness, though in different ways.

Millais paid careful attention to textual details in his painting. Maud's father labors "to thin the crowded groves"(line 35), and indeed the forest has the appearance of a luscious forest floor with humanly wrought spaces between the trees. In addition, appropriate depiction of a country girl's costume was important to Millais, who wrote to his friend in the country in January, 1851, requesting the acquisition of particular accessories that would aid his painting:

Would you ask the mother [of a little girl he had met] to let you have a pair of her old walking-boots?....I do not care how old they are; they are, of course, no use without having been worn....If you should see a country-child with a bright lilac pinafore on, lay strong hands on the same, and send it with the boots. ...I do not wish it new, but clean, with some little pattern — pink spots or anything of that kind. [Millais, 97]

Millais' son wrote that the subject of Ophelia's death had appealed to his father long before he executed it (Millais, 115). However, the short time period in which he painted first The Woodsman's Daughter and then Ophelia seems to link them and perhaps suggest that Millais might have seen his depiction of Ophelia's demise as a fulfillment of Maud's doom. Millais reflects and embellishes his profusion of luminous green nature and attention to botanical details in The Woodsman's Daughter in Ophelia. Beginning with its first showing, Ophelia received special attention from critics and botanists who noted Millais' careful observation and depiction of nature (Millais, 145 and 450-1). although some critics at the time criticized her floating pose as not believable, many people praised its dutiful following of Shakespeare's text (Monkhouse, 58 and 60). Indeed, Millais depicts the willow and the "grassy streame" (Shakespeare, 4.6.167-8), includes Ophelia's garlands, seemingly complete to the untrained eye with "Crownflowers, Nettles, Daisies and long Purples"(Shakespeare, 4.6.170), and paints "her clothes spread wide" in the water (Shakespeare, 4.6.176). Yet his painting also matches Patmore's text, whether intentionally or not: Maud rests by a willow before she drowns (Patmore, line 71); Millais' profusion of plants in the water allows for the possibility of weeds among them (Patmore, line 85); Ophelia's face, like Maud's, appears pale, and each girl in her madness sings, reflected in the figure's open mouth (Patmore, line 28 and Shakespeare, 4.6.178); that the floating Ophelia will soon sink, suggested in the already sinking position of her stomach, also of course conveys the image of Maud, "Sunk in a dread unnatural sleep"(Patmore, line 111). Even if Millais did not intend for these two paintings to act as pendants to one another, their relationship in terms of subject matter and their depiction together of a narrative of soured love and watery death in luscious natural surroundings strongly link them.

Millais' son wrote that the subject of Ophelia's death had appealed to his father long before he executed it (Millais, 115). However, the short time period in which he painted first The Woodsman's Daughter and then Ophelia seems to link them and perhaps suggest that Millais might have seen his depiction of Ophelia's demise as a fulfillment of Maud's doom. Millais reflects and embellishes his profusion of luminous green nature and attention to botanical details in The Woodsman's Daughter in Ophelia. Beginning with its first showing, Ophelia received special attention from critics and botanists who noted Millais' careful observation and depiction of nature (Millais, 145 and 450-1). although some critics at the time criticized her floating pose as not believable, many people praised its dutiful following of Shakespeare's text (Monkhouse, 58 and 60). Indeed, Millais depicts the willow and the "grassy streame" (Shakespeare, 4.6.167-8), includes Ophelia's garlands, seemingly complete to the untrained eye with "Crownflowers, Nettles, Daisies and long Purples"(Shakespeare, 4.6.170), and paints "her clothes spread wide" in the water (Shakespeare, 4.6.176). Yet his painting also matches Patmore's text, whether intentionally or not: Maud rests by a willow before she drowns (Patmore, line 71); Millais' profusion of plants in the water allows for the possibility of weeds among them (Patmore, line 85); Ophelia's face, like Maud's, appears pale, and each girl in her madness sings, reflected in the figure's open mouth (Patmore, line 28 and Shakespeare, 4.6.178); that the floating Ophelia will soon sink, suggested in the already sinking position of her stomach, also of course conveys the image of Maud, "Sunk in a dread unnatural sleep"(Patmore, line 111). Even if Millais did not intend for these two paintings to act as pendants to one another, their relationship in terms of subject matter and their depiction together of a narrative of soured love and watery death in luscious natural surroundings strongly link them.

A Single Linked Vision: Rossetti's Poem and Two Paintings

Dante Gabriel Rossetti completed "Mary's Girlhood (For a Picture)" (1848) and its two accompanying paintings The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) and Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850) all within in short period of time. Two distinctive features mark the creation of this pair of paintings in their relation to a narrative, and distinguish them from the other works discussed here. First, since the poem was intended as a source for the paintings, one might then expect to find a descriptive text, aimed to anticipate and lay a rich visual groundwork for the paintings. Secondly, because writer and painter were one and the same, the usual desire of the second creator to reinvent and leave his mark on the first's work is absent here; thus, one might assume the paintings would provide completely accurate representations of the text. However, neither of these assumptions entirely fits Rossetti's three works on this subject. The relationship of these paintings and the poem is not a matter of illustration and description; instead, they each raise questions that only knowledge of the others can answer. The poem and paintings challenge the reader and viewer to interact with them as an entire set, rather than as individual creations. Rossetti's position as sole creator of these works allowed him the power to mold this relationship.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti completed "Mary's Girlhood (For a Picture)" (1848) and its two accompanying paintings The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) and Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850) all within in short period of time. Two distinctive features mark the creation of this pair of paintings in their relation to a narrative, and distinguish them from the other works discussed here. First, since the poem was intended as a source for the paintings, one might then expect to find a descriptive text, aimed to anticipate and lay a rich visual groundwork for the paintings. Secondly, because writer and painter were one and the same, the usual desire of the second creator to reinvent and leave his mark on the first's work is absent here; thus, one might assume the paintings would provide completely accurate representations of the text. However, neither of these assumptions entirely fits Rossetti's three works on this subject. The relationship of these paintings and the poem is not a matter of illustration and description; instead, they each raise questions that only knowledge of the others can answer. The poem and paintings challenge the reader and viewer to interact with them as an entire set, rather than as individual creations. Rossetti's position as sole creator of these works allowed him the power to mold this relationship.

Divided into two parts, each composed of two stanzas, the poem explores Mary's childhood as well as the traditional symbols associated with the life of the Virgin. The first stanza of part one places Mary in geographical and temporal context and discusses her character. Rossetti does not visually describe Mary, her surroundings or her actions in the poem; instead, he reserves his adjectives for description of Mary's character. Her actions in the first painting subtly reinforce some of the poem's pronouncements, yet they do not blatantly convey the contents of the poem.

Unto God's will she brought devout respect,

Profound simplicity of intellect,

And supreme patience. (I)

These lines of the poem particularly convey Mary's simplicity and lack of learning. Rossetti took issue with earlier painters' depictions of the subject that showed the Virgin engaged in reading, citing the historical inaccuracy of such depictions. In a letter to his godfather in November, 1848, he wrote of The Girlhood of Mary Virgin,

The subject is the education of the Blessed Virgin, one which has been treated at various times by Murillo and other painters — but as I cannot but think, in a very inadequate manner, since they have invariably represented her as reading from a book under the superintendence of her mother, St. Anne, an occupation obviously incompatible with these times, and which could only pass muster if treated in a purely symbolical manner. In order, therefore, to attempt something more probable and at the same time less commonplace, I have represented the future Mother of our Lord as occupied in embroidering a lily — always under the direction of St. Anne. [Rossetti as quoted in Henderson, 18]

Thus, Mary's activity in the painting, though not explicitly suggested in the poem, is significant in that it depicts her engaged in the type of work she actually might have done. This task also emphasizes her "supreme patience," apparent in the way she continues her embroidery, despite the fact that her gaze — directed straight ahead, rather than down at her needlework — indicates that her mind may be elsewhere. The painting does not make clear the subject of her contemplation. Since the poem describes her faith and her "grave peace," it seems likely that she may be contemplating spiritual matters while accepting her current position without question. Indeed, she appears placid, serious and steadfast. Without the poem's clues to her character in the text, however, the viewer might find Mary's expression far more cryptic.

The second stanza of part one describes the Annunciation in the barest, least symbolic terms, relying instead on the change this event produces in Mary's emotions.

So held she through her girlhood; as it were

An angel-watered lily, that near God

Grows and is quiet. Till, one dawn at home,

She woke in her white bed, and had no fear

At all,--yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed;

Because the fulness of the time was come. [lines 9-14]

Rossetti depicts most of this stanza in Ecce Ancilla Domini. Analogous to the poem — in which Mary is described as a growing lily — rather than descriptive of the poem, Mary's completed embroidery of a lily hangs near the end of her bed in the painting. Her bed is white, as in the poem, and the light in the room suggests early morning. Rossetti does not depict her tears, however, perhaps for fear of resorting to sentimentality. Rather, Mary's pose and expression fill in the vague ideas suggested by her feeling of "awe." Her expression and hunched posture convey an intense hesitation, bordering on fear, although the poem states that she did not feel fear.

The second part of the poem contains an explication of the symbolism in The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, begun quite bluntly with the pronouncement "These are the symbols" (line 15). The symbolic explanations connect quite literally to the painting, and provide a kind of key to the painting's meaning, although they are not so much visually described as explicated. For example, Rossetti explains that the cloth on which Mary embroiders a lily is unfinished, suggesting "That Christ is not yet born" (line 18). The poem concludes with the metaphorical transfer of responsibility of caring for Jesus, from God to Mary.

Rossetti inscribed the frame of The Girlhood of Mary Virgin with the lines of the poem, and Maryann Ainsworth notes that since Part II was not originally published, Rossetti must have strongly felt the physical link between poem and painting and their strong tie to each other, which would make separation of the one from the other undesirable (Henderson, 18 and Ainsworth, 6). Not only do the paintings relate to the text, but they relate strongly to each other as well. Mary's embroidery from The Girlhood of Mary Virgin reappears completed in Ecce Ancilla Domini to suggest that the time has come for the Annunciation. Furthermore, unlike in some groupings of paintings, such as Waterhouse's three paintings of the Lady of Shalott discussed below — each with a different depiction of his protagonist — Rossetti's Mary is quite clearly the same girl in both paintings.

Creating a Narrative without a Long Text: Egg and the Expansion of a Brief Quotation

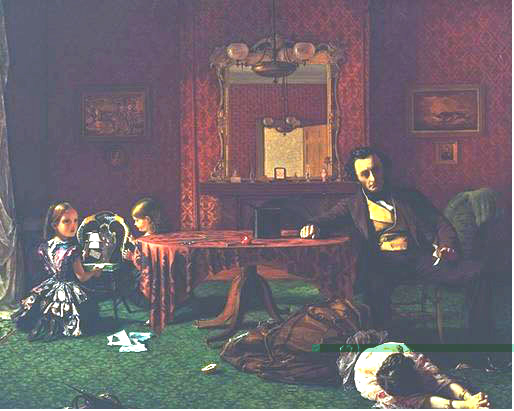

Although Augustus Egg's series, Past and Present (1858) does not draw from a single text, it strongly conveys a narrative developed from a single quote that encapsulates the three images. Since Egg originally exhibited the series without a title, this quote served that purpose and to some extent summarized and explained the contents of the paintings: "Aug. 4: Have just heard that B. has been dead more than a fortnight; so his poor children have now lost both their parents. I hear she was seen on Friday last, near the Strand, evidently without a place to lay her head — What a fall hers has been!"(Lister, 54). Strikingly, the quote provides merely a temporal framework, with the symbols within the paintings giving most of the narrative clues.

The Infidelity Discovered, part 1 of Past and Present by Augustus Egg

The first painting in the series contains the seated husband, holding a letter with evidence of his wife's adultery. His wife has literally fallen to the floor after he has confronted her with his knowledge. Her physical fall recalls the final sentence of the quote about a metaphorical fall. The apple she presumably cut has significantly fallen to the floor, reminding the viewer of the edenic fall. Paintings of the "The Fall" and "The Abandoned" — a shipwreck — decorate the walls and hang above images of the wife and husband, respectively and symbolically. Their two young daughters build a house of cards, and the common fate of all card houses foreshadows the doom of this household (Lister, 54). The open door, reflected in the mirror over the mantel, perhaps foretells the exit this woman must now make from her comfortable home and loving family. The strongly shocking, havoc-ridden nature of the scene — a living woman sprawled face down on the floor and a child staring in intense confusion at an interaction she should not be allowed to witness — contrasts strongly with the warm, cozy interior, carefully decorated and depicted with precise attention to details. Light enters Past and Present: I from a window outside the frame of the painting on the left, though indicated by the folds of a long curtain, and illuminates the faces of the little girls, one looking up, the other down. The unlighted gasolier and shadowy room suggest that it may be late afternoon.

Left: The Abandoned Daughters by Augustus Egg<. Right: The Wife Abandoned By Her Lover With Her Bastard Child by Augustus Egg. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

A different mood and lighting infiltrate the two subsequent paintings in the series that seem to depict "Friday last." A hidden lamp or candle provides a warm glow in Past and Present: II and an overhead lantern creates patches of light and eerie shadows in Past and Present: III. Egg depicts the moon in a framed sky in these two paintings — bordered by a window in one and an archway in the other — and in each, the moon's identical phase and the sliver of lighted sky beneath it suggest that they depict the same moment in two different locations (Lister, 56 and 58). In the first, the two daughters sit beside a window in a bedroom that, though not decrepit, certainly appears bare compared to the parlor of their youth. As in Past and Present: I, one daughter looks upward, the other downward as she buries her head in her sister's lap. Also linking explicitly back to the prior painting, the two framed likenesses of the parents once again hang on the wall, here on either side of the window. No longer a mood of shock and sudden despair, of illuminated treacheries and garish incongruities, this scene shares with the third one a deep melancholy and sadness. although the kneeling sister humbles herself, as her mother did in the first painting, a resigned, continuous pain characterizes this scene, rather than a sharp agony and fear. Raymond Lister writes that in Past and Present: II, as the daughters mourn the recent death of their father, they pause to wonder what has happened to their mother over the years (Lister, 58).

Egg answers their query, though he offers his response to the viewer, not the daughters. Past and Present: III shows the mother, nursing a likely illegitimate child, seated in the cavernous, covered area beneath two arches and surrounded by rocks and barrels with a view of the Thames and distant buildings (Lister, 58). Posters cover the wall behind her, with various significant words and phrases visible such as "Victims," "A cure for love," "Pleasure excursions to Paris" and "Return"(Lister, 58). The mother gazes up at the moon, and Lister writes that she wonders about the fate of her daughters at the same moment that they think of her (Lister, 58). Thus, rather than a linear continuation of a narrative, Egg begins with the past and follows this past with concurrent images of the present. The past's legacy strongly colors these scenes of the present: literally, the colors in the later two paintings appear subdued and tranquil compared to those in Past and Present: I. Furthermore, although he uses no lengthy text as a source, Egg's economy of images and efficient use of symbols in the paintings to convey meaning mirrors the conciseness of the quotation.

Imagining a New Mythical World: Burne-Jones' Interpretation of Morris' "The Doom of King Acrisius"

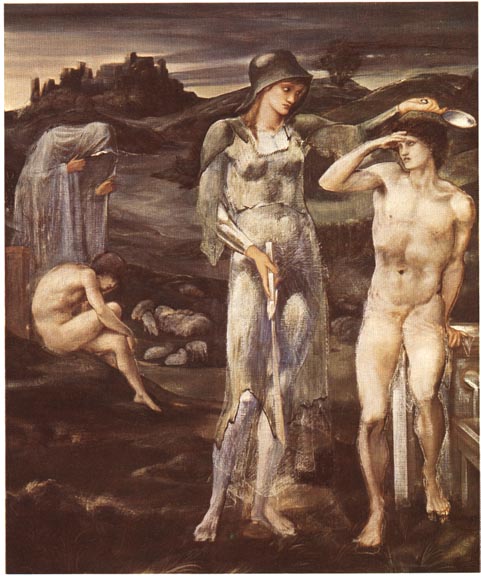

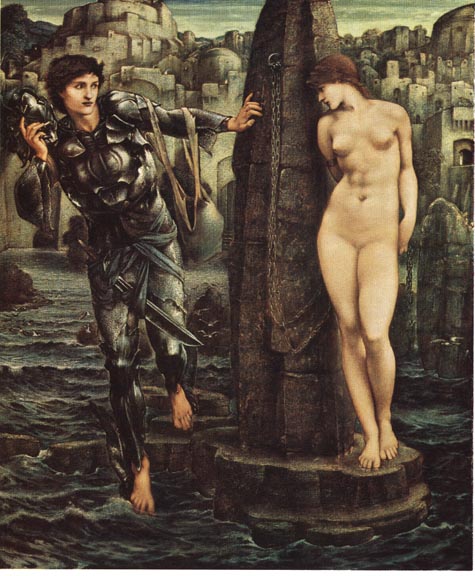

Sir Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris had been friends at Oxford, and Burne-Jones, throughout his career, illustrated Morris' poetry and created paintings inspired by it (Cody, Victorian Web). Burne-Jones used "The Doom of King Acrisius" from Morris' the Earthly Paradise (first edition 1868-70) as the source for his Perseus Series (1875-85), commissioned by Arthur Balfour (Spalding, 45-6). although he showed The Baleful Head at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1887 and subsequently exhibited The Rock of Doom and The Doom Fulfilled at the New Gallery's 1888 opening, several other images in the series remained cartoons, never executed as finished products, and yet others Burne-Jones began in oil but left unfinished (Cartwright, 24).

although inspired by Morris' text and clearly using it as a source, Burne-Jones certainly did not let the text play a constraining function in his process. An exploration of the text and the paintings yields certain patterns in Burne-Jones' tendencies when transforming another's written narrative into his own painted narrative. He generally depicts moments that occur within Morris' text and limits himself to the figures Morris presents in a scene. However, he departs from Morris' text by idealizing these figures, portraying no one as old or ugly, not following Morris' descriptions of costumes and poses, and limiting the number of objects and textual details he includes in his paintings. Furthermore, he has virtually no use for Morris' placement of scenes indoors; instead, he resituates the story entirely outdoors, with the first four scenes set in vague, rocky areas with bizarre lighting, the fourth and fifth set in similarly rocky but now also watery areas, the seventh, though in the same place as the sixth, in a more confined and almost cavernous space, and the eighth against a rich backdrop of foliage in a garden with a surrounding bench and a small pool. although these changes to Morris' narrative and exclusions of details sometimes obscure the story, they allow Burne-Jones to create a new sequential story and world, albeit one still closely tied to Morris' narrative.

The Calling of Perseus from the Perseus series by Edward Burne-Jones. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Burne-Jones depicts two moments in the first painting, The Calling of Perseus, the first in the background and the second in the painting's foreground, as alluded to earlier. In the background scene, Burne-Jones cloaks the "ancient woman....bent with weight of many a year" who approaches Perseus and depicts her hunched over as in the text, to convey her age yet avoid displaying any details of her ugliness (all quotes in this section drawn from the portions of Morris' "The Doom of King Acrisius," I, 248-77, quoted on the Victorian Web). The foreground scene contains Perseus and the woman after she has transformed into the youthful, powerful Pallas. although his depiction of her generally follows Morris' text closely, he changes Pallas' "many-coloured Indian silk" into a pale grey, in some places transparent material, darkens her hair from amber to a more auburn shade, and covers her arm with material when Morris indicated it was bare. However, by separating this scene into two moments, pre- and post-transformation, Burne-Jones makes it more difficult for a viewer less familiar with the story to discern that the two female figures are the same character. His alteration of Perseus' pose — from standing "with bowed head...and outstretched hand" to falling into a seated position with his hand at his brow, shielding his eyes, and his gaze directed upward at Pallas — still powerfully conveys the awe and respect Perseus feels for Pallas, even as Burne-Jones conveys these by means of a different pose.

Perseus and the Graiae from the Perseus series by Edward Burne-Jones. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

As noted, Burne-Jones removes the architecture from many of these scenes, setting them in otherworldly, rocky locales, and he does this in Perseus and the Graiae. Rather than sitting on a high dais in "a mighty hall" with a "white marble wall," the three sisters squat on the ground before hazy, rocky mountains. He idealizes the figures, changing the long white hair that trails down their backs in the poem into upswept, dark, graceful buns, and slightly altering their clothes. Far from the "dreadful," wrinkled faces Morris describes, these women appear pretty and youthful. Though they share but one eye for the three of them, Morris conveys their blindness not with literal depiction of deformity or even vacant stares, but rather by closing the eyes of the one sister who faces the viewer. Burne-Jones depicts the moment of Perseus reaching for the eye, which the sisters pass amongst them. Yet Burne-Jones does not clearly depict the eye, and Perseus seems to calmly reach towards them rather than to swiftly snatch away their prize possession. Thus, Burne-Jones again obscures the moment of action he draws from Morris' narrative in the interests of creating a beautiful, tranquil scene. He preserves the symmetry of the scene by presenting the moment before the eye has been stolen and so before the third sister rises to a standing position.

Left: The Death of Medusa from the Perseus series by Edward Burne-Jones.

Right: The Hero Arrives from the Perseus series by Edward Burne-Jones. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Despite certain departures from the poem in The Death of Medusa and The Hero Arrives, Burne-Jones nonetheless quite precisely depicts particular temporal moments from Morris' poem in these two paintings. He effectively conveys the "whirl[ing]" chaos as Perseus slays Medusa in the first of those paintings. In addition, the two immortals who dwelt with her rise up, as they do at a precise moment in the poem. In the second of these paintings, Perseus has just removed the cap that gave him invisibility, allowing the lovely Andromeda to see him standing "before her with flushed face at last," and as she turns her face modestly toward the stone, the chains pull her right arm backward as though in resistance to her attempt to conceal her nakedness, as Morris describes. Burne-Jones does not allow "tresses of her hair / That o'er her white limbs by the breeze were wound" to cover her frontal nudity, instead pulling it behind her head.

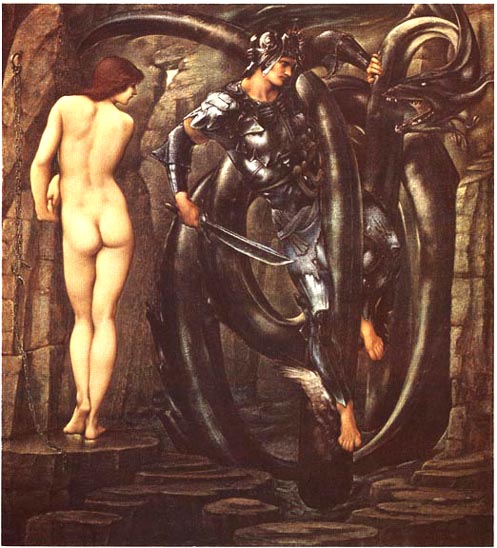

The Hero Triumphs [The Doom Fulfilled] from the Perseus series by Edward Burne-Jones. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

One of the most striking and active paintings in the series, "The Hero Triumphs depicts Perseus' battle with the monstrous serpent. Burne-Jones compresses the scene in order to include the nude Andromeda — now viewed from the back to complement the previous image — directly beside Perseus' struggle. She still stands upright, unlike in the poem, allowing Burne-Jones again to paint the pale and lovely nude body, this time beside the dark serpent. Unlike Morris' red-eyed creature, "Maned with grey tufts of hair," Burne-Jones' serpent has silver eyes and a smooth, metallic surface resembling a darker shade of Perseus' armor. Thus, Burne-Jones maintains the elegant beauty and small, cool spectrum of colors used in the other paintings. He precisely conveys the moment of the story at which his scene occurs: when Perseus stands in the "confused folds" of the monster. However, Burne-Jones does not depict Morris' description of what makes the monster so terrifying, such as the frightening shadows it casts or the strong wind of its venomous breath. Instead, Burne-Jones' rendition of the scene emphasizes Perseus' physical strength that seems to guarantee and foretell his triumph, even as he stands enwrapped in the monster's clutch.

Interestingly, Burne-Jones' The Tower of Brass, also exhibited in 1888 at the New Gallery though not a part of the series, serves as a kind of prequel to the series, portraying Danäe, Perseus' mother, gazing at the construction of a tower in which her father has ordered her imprisoned. Her father, King Acrisius, knew that the birth of his grandson would signal his own demise (Cartwright, 24).

A Backward Journey through the "Lady of Shalott": John William Waterhouse

John William Waterhouse painted three depictions of Alfred Lord Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott" over the course of his life, with the first and final versions separated by close to thirty years. Surprisingly, his choice of moments to portray moved backwards through the story as his own life moved forwards. Thus, unlike other situations here discussed, in which groupings of paintings generally were created with the fictional progression of time and time in the artists' lives moving in the same direction, Waterhouse continued to reinterpret "The Lady of Shalott" by delving deeper and chronologically farther back into the life of the Lady. Consequently, it may be possible to view the three images as increasingly probing considerations of the Lady's motives and mindset as she sets off on her ultimate course.

The Lady of Shalott by J. W. Waterhouse. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Waterhouse first chose to depict a moment from Part IV of the poem, in which the Lady has left her interior confinement to come out into the world. Nature surrounds her in this 1888 version, with a brown forest of trees behind her and rushes and water lilies in the stream beside her. The viewer can see the stone steps of the dock, from whence the Lady presumably came, and she holds the chain of the boat in her hand — these two aspects suggesting that she has only just now begun her journey outwards down the river. The fact that she still sits upright in the boat, rather than in a supine position, locates the exact moment even more closely, to the middle of the line, "She loosed the chain, and down she lay." Thus, Waterhouse portrays the Lady at the last point at which she actively engages in her life. This has been a short period of time for her: from deciding to reject the second-hand world she has experienced and instead looking directly out at the world, leaving her tower to experience that world, and claiming and setting in motion a boat as her final destination. The Lady has an apprehensive, tense expression, her chin raised almost defensively — she has not yet relinquished her autonomy to fate — and her eyes seek to penetrate something in the distance, no doubt Camelot as the poem suggests.

Far more so than in the other two paintings, this woman seems to embody the idea of "the fairy Lady" as the reapers called her (I), and Tennyson's descriptions of her as "glassy" and "like some bold seer in a trance"(IV) seem appropriately captured in her almost delirious tension. Her pale, waiflike complexion, wispy golden hair, and delicate features indicate her fragility in this new world she has entered. Dressed in white as described in the poem, her own paleness and delicacy contrast with the brightly colored tapestry she has woven and brought with her, the warm greens and browns of the natural world, and the strong, solid presence of the wooden boat.

For his second version, painted just six years later in 1894, Waterhouse moved back in the poem to the decisive moment at which the Lady takes action and changes the course of her life. This instant, then, explains how the Lady reached the moment he had already shown of her last grip on her life before she lay down to drift and die. In painting this precursor to his depiction of her in the boat, then, Waterhouse selected another key moment of the Lady's autonomy when she is still in her tower. The mirror, which previously provided her only view of the world, now stands at her back. She has arisen rapidly from the loom causing the entanglement her legs in threads of her web, and she now lurches toward the front of the painting to look out the window at the world. The cracks in the mirror behind her and her position looking outward indicate that the moment evoked here represents "'The curse is come upon me,' cried / The Lady of Shalott"(III).

In contrast to his previous image, in which luscious nature played a large role in the scene, in this painting only a small portion of the canvas depicts the natural world. Instead, the dark, confining nature of her room predominates, and a luminous patch of green in the mirror suggests the tantalizing brightness of the outside world. Until this point, she has only seen the world indirectly; now, Waterhouse places the viewer in her position, observing nature only as a gleaming patch in a mirror. In addition, he also paints Lancelot's helmet in the mirror, a reminder of what triggered the Lady's rejection of her old existence.

Here again, he portrays the Lady dressed in white, in a gown similar in style to that in his first version. However, he alters the appearance of the Lady: no longer waiflike and golden-haired, this Lady has rosy, flushed cheeks, bright pink lips, and thick dark hair that disappears down her back rather than spreading over her shoulders. Waterhouse conveys a strong sense of her body beneath the wrinkles of her dress. Her intense gaze suggests the doom she knows awaits her.

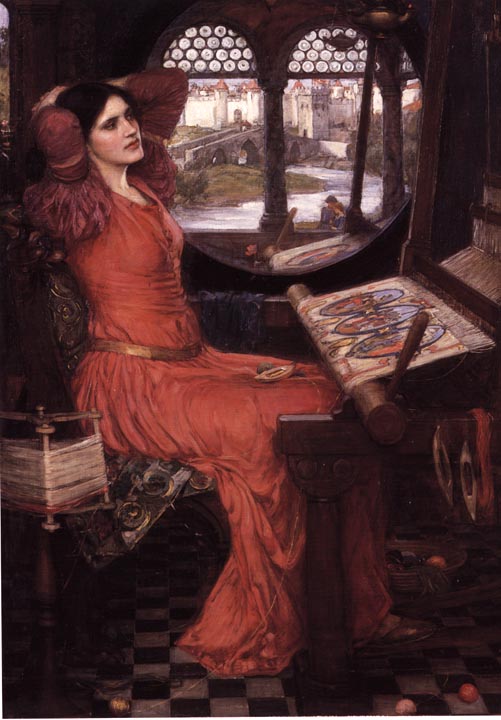

"I Am Half-Sick of Shadows," Said the Lady of Shalott by J. W. Waterhouse. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

Twenty-one years elapsed before Waterhouse again portrayed the Lady of Shalott in "I Am Half-Sick of Shadows," Said the Lady of Shalott (1915). In this painting, once again, the viewer faces the mirror. This circular mirror, not shockingly, dictates the shape of the Lady's woven images. Her woven tapestry with three of "the mirror's magic sights"(II) sits brightly before her as she pauses in her work. The reflection of part of this tapestry in the mirror reminds the viewer of the infinite images that have passed before her eyes, only to be copied by her second-hand, rather than lived. For the first time in this series, Waterhouse illustrates in this mirror an outside world according to the details with which Tennyson described it: "the river winding clearly, / Down to tower'd Camelot"(I). However, Waterhouse alters the time of day from moonlit evening to sometime during the day. He includes in the landscape the "two young lovers lately wed"(II) who cause the Lady to pause in her work and contemplate the life she is missing.Yet this circle of the outside world, for all its minute details, lacks the eye-catching brightness of that in his 1894 painting, if only because it must here compete with the very brightness of the Lady herself — a figure quite distinct from his earlier two versions of her. Unlike in the other two paintings, Waterhouse here paints the Lady dressed in a garish pink-red dress. although Tennyson mentions the red garments of girls and boys in the town in two places (II), his only description of the Lady's clothes comes near the end when she wears white, as noted. Thus, Waterhouse's decision represents a clear choice unrelated to description in the poem. The decadent appearance of her gown and the fine gold thread she uses to weave perhaps serve to contrast with the unfulfilled, pensive expression on her face: riches and lovely creations cannot satisfy her loneliness or justify her isolation.

Elizabeth Nelson points out that Tennyson's lack of description of the Lady and focus instead on her surroundings increase the Lady's aura of mystery (Nelson, 4). These aspects of the poem also allowed Waterhouse greater freedom in his depictions of the Lady herself. He clearly felt free to entirely reinvent the Lady with each further probe into the poem, changing her hair color, her features, her clothing and her mood as he sought to explore her role in determining her fate. Yet even as his three paintings seem to present three different women, the images connect strongly as a narrative trio and as different states in an artistic process: they demonstrate Waterhouse's gradual, backward-moving search to visually explain the Lady according to a careful reading of his poetic source.

Conclusion

The creation of series of paintings linked by a narrative had been done many times before the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers painted the works discussed above. In the century before these men worked, William Hogarth had created numerous series of images telling stories by means of the paintings' or prints' details, relationships to each other, and occasionally the text he placed within the images themselves. The Pre-Raphaelites admired Hogarth and his methods of conveying narratives, particularly those with moral messages. Yet in the case of Hogarth, for example in the Rake's Progress (1733), the primary goals consist in conveying the story's moral and the protagonist's choices that lead him to it. Numerous other issues arise in the pairs and series of paintings discussed above specifically related to their context and time. In particular, in the paintings and poetry of Millais, Hunt, Rossetti, Egg, Morris and Burne-Jones, their artistic and social milieu and shared ideals crucially affected their products.

Millais' and Hunt's friendship, discussions and similar goals certainly created a pronounced effect on the relationship between their two paintings of Keats' poem. Because Millais painted both The Woodsman's Daughter and Ophelia and within a short period of time, one can see a particular link between these narratives as bookends to a girl's life, each dealing with tragic love surrounded by natural beauty. The Pre-Raphaelites' interest in creating both poetry and painting — most successfully and doggedly pursued by Rossetti — reaps its just rewards in the powerful trio of his works and the way that he uses the two media to expand upon as well as depend on each other. Egg's series differs from the others discussed in that he does not use a narrative but merely a brief text. Yet as in Rossetti's poem and paintings, Egg's work requires one to consider both text and images to fully appreciate and understand the narrative he conveys. As close friends, Burne-Jones and Morris clearly influenced each other's works, and an exploration of Morris' text and Burne-Jones' images of the Perseus story suggest what narrative issues mattered strongly to each man, and the extent to which artists can take liberties with a text if they still hope to convey certain aspects of a story.

In selecting a commonly illustrated poem, Waterhouse needed to reconsider the poem closely in order to create images faithful to the text and not already depicted by earlier artists. although his second and third versions of the Lady of Shalott bear certain resemblances to Hunt's drawing and painting on that topic — the circular mirror, the archways outdoors, a claustrophobic space, and threads that entangle the Lady — his images nonetheless differ from Hunt's. He creates less crowded, cluttered images, and his scenes have a believable quality quite different from the fantastical nature of Hunt's scene with the Lady's hair standing magically in air overhead. Moreover, as three linked images, Waterhouse's paintings --as well as all the sets of paintings discussed here — have the ability to show a progression and change that compellingly parallels the nature of described change within a narrative. Yet unlike in literature, in which a continuous flow of words describes a story, in these series of paintings, the artists depict the narratives as frozen moments in time, with the ties between them suggested and expanded upon in the viewer's mind, rather than on the printed page.

References

Ainsworth, Maryann Wynn. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Double Work of Art. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1976.

Antal, Frederick. Hogarth And his Place in European Art. New York: Basic Books, 1962.

Cartwright, Julia. The Life and Work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones. London: The Art Annual, 1894.

Cody, David. "William Morris: A Brief Biography." Victorian Web.

Henderson, Marina. D.G. Rossetti. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973.

Hunt, William Holman. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood vol. 1. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1905.

Landow, George P. The Woodsman's Daughter. Victorian Web.

Lister, Raymond. Victorian Narrative Paintings. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1966.

Millais, John G. The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais vol. 1. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1899.

Monkhouse, Cosmo. British contemporary artists. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1899.

Nelson, Elizabeth. "Tennyson and the Ladies of Shalott" in Ladies of Shalott. A Victorian Masterpiece and its Contexts. An Exhibition by the Department of Art, Brown University. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University, 1985.

Spalding, Frances. Magnificent Dreams. Burne Jones and the Late Victorians. Oxford: Phaidon, 1978.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Seven Dials, 2000.

Last modified 5 March 2005