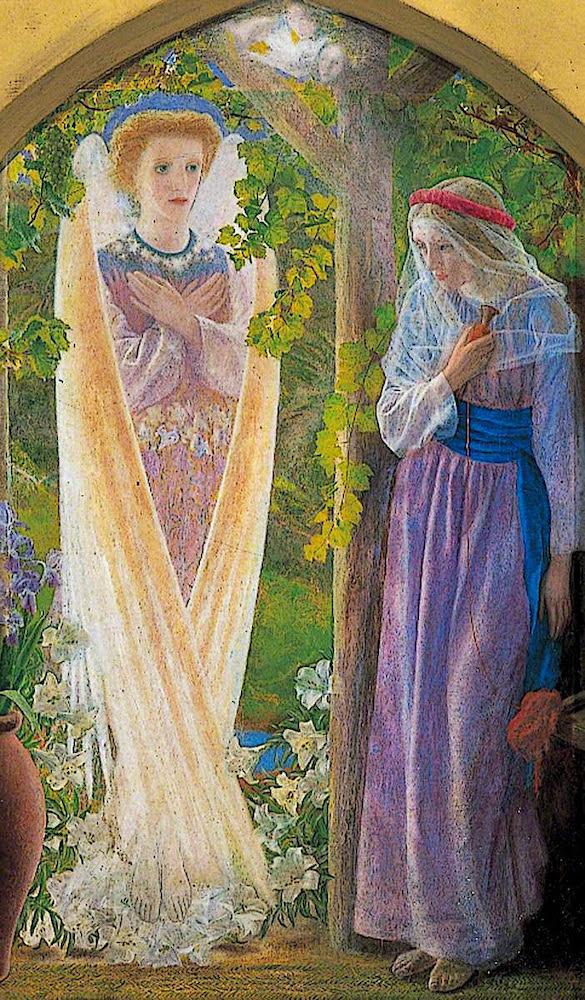

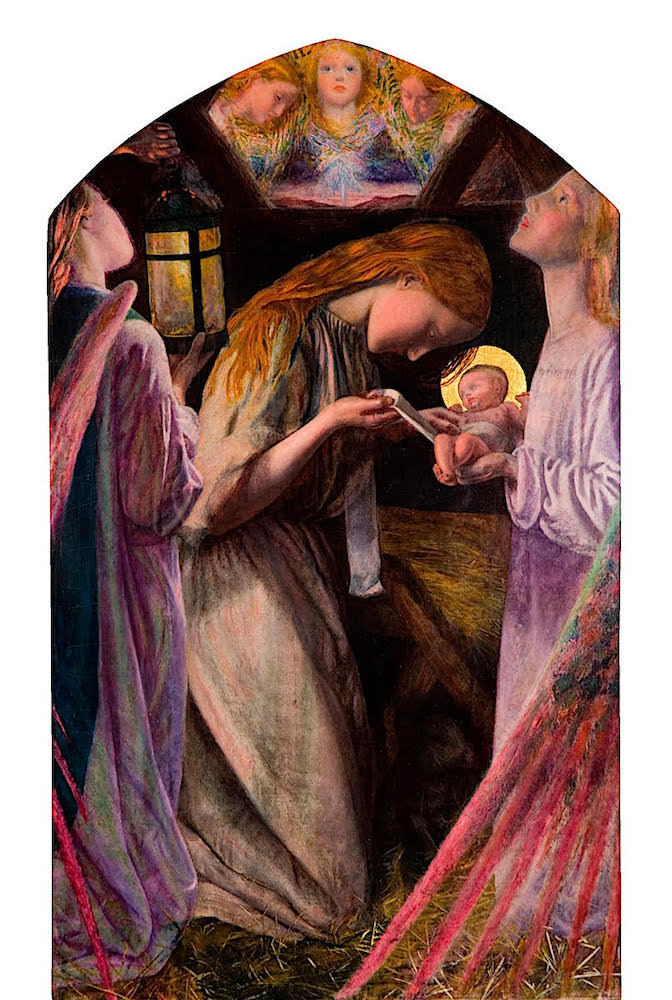

The Annunciation and The Nativity, by Arthur Hughes (1832-1915). 1857-58. The Annunciation: Oil and pencil on canvas. 24¼ x 14¼ inches (61.3 x 35.9 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, accession no. 1892P1. The Nativity. Oil and gold leaf on canvas. 24¼ x 14¼ inches (61.2 x 35.8 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museums Trust, accession no. 1892P2. Images released by the Birmingham Museums Trust under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero licence (CCO). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

These two religious works have generally been considered as a pair because they are the same size and framed identically, are from the same date, and are thematically related. In 1858 both paintings were submitted to the Royal Academy but only The Nativity was accepted for the exhibition, no. 248. John Ruskin remarked in his Academy Notes that he knew The Nativity to have been "hastily finished," and The Annunciation may possibly have been even less finalized, resulting in its rejection. Even D. G. Rossetti commented on how the former was inadequately finished in a letter to William Bell Scott of c. June 21, 1858: "It is a frightfully seedy Academy. Not a picture which is not done in prose (nor always in grammar). Perhaps Hughes's little Nativity might be the one exception were it better finished" (Rossetti, letter 58.6, 213).

Hughes may not have resubmitted The Annunciation to the Royal Academy exhibition of 1859 because it was such an obvious pendant to his previous year's exhibit. The Annunciation shows the Virgin Mary, veiled and clad in a lilac robe with a blue belt round her waist, startled and fearful at the sudden appearance of the Archangel Gabriel. The scene is set in the brilliant sunshine and plants such as the white lilies, purple irises, grapes, and the ivy are included for symbolic purposes. The Nativity is set in the evening in a humble stable. A very young redhaired Virgin Mary is wrapping the Christ child in swaddling clothes prior to placing him in a manger and is assisted by two angels. Three further angels look down upon the scene from above. Both paintings were initially owned by the famous Pre-Raphaelite collector Thomas Edward Plint.

Modern Opinions on the Paintings and the Influence of Pre-Raphaelitism

As Julian Treuherz has pointed out these works have many features of Pre-Raphaelitism and were particularly influenced by the works of D. G. Rossetti:

Both paintings depict traditional religious subjects in a new way, rejecting medieval or Renaissance precedents, a characteristic of Pre-Raphaelitism. Other typical Pre-Raphaelite features are the fine painting of detail, the angularity of the figures, and the confined, shallow space which pushes the figures, especially in The Nativity, close to the viewer, giving the scene startling immediacy. The paintings owe much to the influence of Rossetti: as in Rossetti's Ecce Ancilla Domini! Hughes shows the angel Gabriel with a strong vertical emphasis, hovering above the ground and Hughes has also taken from Rossetti's The Annunciation (1855, Private Collection) Gabriel's enfolding wings, crossing in front of his body. In The Nativity Hughes follows a scheme much used by Rossetti, with a central figure flanked by two figures in mirroring poses. But the singing colours and the gentle delicacy of feeling are hallmarks of Hughes' own style. [168]

Stephen Wildman felt there were certain uncomfortable features about The Annunciation which made it a less appealing picture than its companion piece:

Although the angel is meant to represent an unearthly figure, the body is stiff and the expression blank, while its juxtaposition with the foliage is rather contrived, as is the placement of the angelic heads and dove at the apex of the image. It is as if Hughes were attempting to combine the striking composition of Rossetti's Annunciation picture, Ecce Angeli Domini! with Millais's observation of natural detail…. Nevertheless, Hughes makes telling use of simple elements to reinforce the symbolic nature of the subject. Lilies and irises denote the Virgin's purity and innocence, while the angel hovers at the doorway, which thereby becomes the threshold between Mary's present humility and future glory" (171). In terms of The Nativity Wildman felt, like Treuherz, that there was little hint of Hughes having followed any medieval or Renaissance precedent: "The Nativity impresses the viewer through its freshness of treatment, simple strength of composition, and subtlety of colour … instead he offers in addition to the Christ child, a touching group of young female figures (at which he excelled) that combines realism with mystery. [174]

Unusual Religious Symbolic References in the Painting

Victoria Osborne has emphasised the religious symbolic references in the two paintings and how they differed from conventional artistic portrayals of these common biblical scenes:

These two pictures, with their tender mood and bright, luminous color, are typical of Hughes's early Pre-Raphaelite paintings. In The Annunciation, Mary draws back, startled, at the sudden appearance of the angel; the scene is frozen at the moment the skein of wool has dropped from her hand but not yet hit the floor. The hieratic figure of the angel is surrounded by lilies and irises, denoting, respectively, the Virgin's purity and her future sorrows; the vine leaves, delicately glowing from the sacred light, prefigure Christ's passion, and death. The Nativity offers an intimate and unconventional interpretation of the familiar scene, excluding Joseph and the traditional supporting cast of animals, shepherds, or magi to focus on the bond between mother and child. Hughes emphasized Mary's youth and inexperience: dressed in a simple shift, with her red hair loose, she bends over the baby Jesus with an intense concentration, delicately wrapping him in swaddling bands, while one angel supports the infant and another raises a lantern to light the scene. In its lack of pretension and attempt to convey the emotional impact of new motherhood, it exemplifies the Pre-Raphaelite attentiveness, in John Ruskin's words, to 'what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent, irrespective of any conventional rules of picture making [136-37].

Contemporary Reviews of the Pictures

John Ruskin in his Academy Notes defended the religious simplicity of this painting and the role of ministering angels as well as admiring Hughes's power as a colourist:

Quite beautiful in thought, and indicative of greater colourist's power than anything in the rooms; there is no other picture so right in manner of work, the utmost possible value being given to every atom of tint laid on the canvas. I happen to know that it was hastily finished, in an afterthought; and I am sorry to see that the painter has been fatigued to the point of not seeing how far he had failed in some parts of his purpose…It is quite possible that, in this nativity, thoughtless people may be offended by an angel being set to hold a stable lantern. Everybody is ready to repeat pretty verses from Spenser about angels who 'watch and truly ward,' without ever asking themselves what they look out for, or what they ward off; everybody is also ready to talk about ministering spirits, so long as it is not asked what ministry means. Perhaps they might even reach to a distinct idea of such practical ministries on the part of angels as warding off a bullet from their son in India, or leading him to a spring when he was thirsty. But they cannot conceive that highest of all dignity in the entirely angelic ministration which would simply do rightly whatever needed to be done—great or small—and steady a stable lantern if it swung uneasily, just as willingly as drive back a thunder-cloud, or helm a ship with a thousand souls in it from a lee shore [162-63].

The reviewer for The Art Journal decried the unusual nature of the subject as it was portrayed: "No. 284. The Nativity, A. Hughes. This is a kind of extravagance for which it is not difficult to account, since there is extant so much fanaticism in painting. The angel holding the lantern for the Virgin to swathe the infant, which is held by another angel, is a conception existing, we believe, at Cologne. There is some good execution in the work, but its pretension is unlike anything in heaven, or on earth, or in the waters under the earth" (166). The critic for The Athenaeum also failed to be impressed finding the conception eccentric and puerile: "The Nativity (284), by Mr. Hughes, too often wilfully eccentric, seems to us – though Mr. Ruskin calls it beautiful in thought and indicative of colour, and admires the phosphoric lilac angel with the stable lantern – a silly puerility. The mean care with which the violet-coloured angel twists the tape around the child is laughable, were not the whole thing pitiable as a clever poetical man's aberration and sectarian folly" (629).

W. M. Rossetti in The Spectator initially merely stated: "In the Middle Room are a small, but truly lovely, Nativity, by Mr. Hughes, in which the holy simplicity of the old Praeraffaelism is marred by the executive ease of the new" (471). In a later review, however, Rossetti felt this painting was the finest work yet produced by Hughes in terms of its conception, design and aim:

In the present exhibition there is exactly one worthy religious picture – the Nativity, by Mr. Hughes. It is not a grand work in any sense – small in size, condensed in treatment, slight in execution; but it is exquisitely pure in feeling, and delicious in colour. Reverence and joy are the soul of it throughout; and, aided by the chaste, sweet young faces, and the glow-worn radiance of the angels, give it a certain look truly heavenly. Mr. Hughes's is not precisely a naturalistic treatment of the subject, nor precisely an abstract treatment; but a something between the two, of which he is not indeed the first to furnish the type in the school whereto he belongs, but which, as here embodied, we can see to be very nearly the right medium for our own day. The more robust principle of giving simply the human facts of the event would fail in any save the most powerful hands, and perhaps would scarcely even realize the subject so truly. One point where the painter has felt and expressed very charmingly is the contrast between the supernaturalism of the angelic figures and the merely natural effect and treatment of the stable, the scene of the Nativity, and all that pertains to that. In conception and design, as well as in the aim though not the completeness of his execution, we rate this little work higher than anything heretofore produced by Mr. Hughes [503].

Bibliography

The Annunciation. Art UK

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1594 (May 15, 1858): 628-30. The Nativity. Art UK. Web. 5 March 2025. Osborne, Victoria. Victorian Radicals. From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts & Crafts Movement. New York: American Federation of Arts, 2016, cat. 34, 136-37. Roberts, Len. Arthur Hughes His Life and Works. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1997, cat. 36 and 37, 142. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Formative Years, II. 1855-1862. William E. Fredeman Ed. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002, letter 58.6, 212-15. Rossetti, William Michael. "Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XXXI (1 May 1858): 470-72. Rossetti, William Michael. "Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XXXI (8 May 1858): 502-04. "The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series IV (1 June 1858): 161-72. Ruskin, John. "Academy Notes." The Works of John Ruskin, XIV, edited by E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. London: George Allen, 1904, 163. Treuherz, Julian. The Pre-Raphaelites. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2009, cat. nos. 38 and 39. Wildman, Stephen. Visions of Love and Life. Pre-Raphaelite Art from the Birmingham Collection, England. Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International, 1995, cat. nos. 46 and 47. 171-74. Created 5 March 2025