he Etruscan School was one of the major forces in British landscape painting in the second half of the nineteenth and into the early twentiethth century. According to Giuliana Pieri “It introduced a new style of landscape paintings in which purely compositional and formal elements were central to the artist’s vision” (297). This movement consisted primarily of a circle of English painters who had worked in Italy at some stage of their careers and who had been inspired by the landscape work of the Italian artist Giovanni “Nino” Costa. Costa’s studio on the Via Margutta in Rome became a popular meeting place for English painters visiting the city in the second half of the nineteenth century. The name Etruscan School was taken from Costa’s nickname “The Etruscan,” derived from his birthplace in the Trastevere district of Rome that formed part of the ancient Etruria. The name of this group as the Etruscan School was never widely accepted, however, at the time of its formation.

Artists Associated with the Etruscan School

The formal association of this group of painters did not begin until 1883, but the roots of this movement stretch much further back to when Costa was painting in the Roman Campagna in the company of his English friends George Heming Mason and Frederic Leighton in the early 1850s. Costa had met Mason in 1852 and Leighton in 1853 and both became his life-long friends. In 1866 George Howard and William Blake Richmond first made the acquaintance of Costa and in 1872 Leighton introduced Walter Crane to Costa.

When the Etruscan School was founded in the winter of 1883-84 its membership included the English painters Howard, Richmond, Edgar Barclay, Walter Maclaren, Matthew Ridley Corbet, Edith Murch [later Corbet], and the Hon. Walter James. Artists considered associated with the group, although not formal members, included Leighton, Mason, Crane, and John Collingham Moore. The Italian painters included in the group consisted of Giuseppe Cellini, Gaetano Vannicola, Cesare Formilli, Napoleone Parisani, and Norberto Pazzini. All these artists had found inspiration in sketching trips into the Roman Campagna, both guided and encouraged by Costa. The English painters associated with the Etruscan School initially exhibited their landscapes primarily at the Dudley Gallery and then at the Grosvenor Gallery when it opened in 1877. They later transferred their allegiance to the New Gallery in 1888 when it took over from the Grosvenor Gallery as the showcase for progressive painters, particularly those associated with the Aesthetic Movement.

Stylistic Characteristics

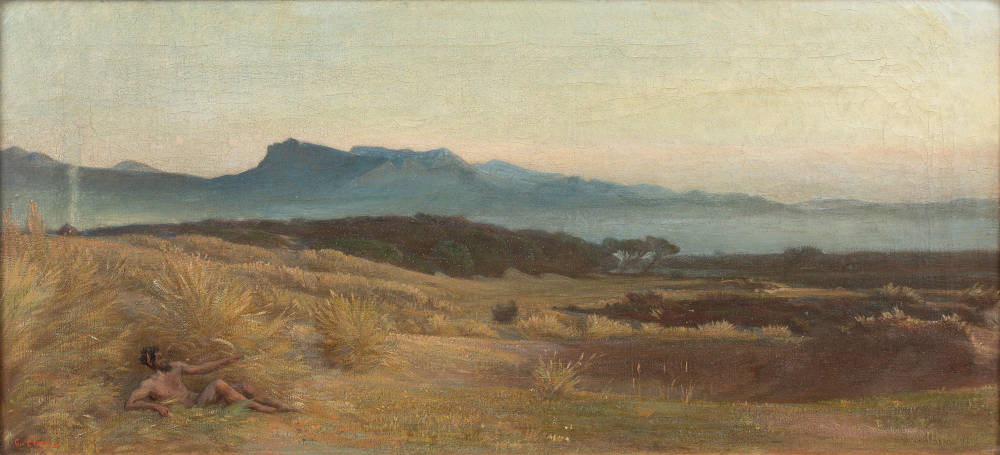

Costa's Campagna Romana near Acqua Acetosa. c.1883. Oil on wood; 97/8 x 32 inches (25 x 81 cm). Collection of William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, catalogue no. Br072.

The Etruscan School style of painting was characterized by breadth of handling, subdued tonalities, and broad panoramas. The focus of the Etruscan School was on a general impression of the landscape rather than focusing on minute details such as was emphasized during the first phase of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting. According to Bill Waters, the formation of the Etruscan School was “based on the principle of sentiment achieved through a process of abstraction founded upon direct experience of nature” (The Etruscan School, Fine Art Society, 4). Pieri has pointed out the features that he felt epitomised the Etruscan School of landscape painting:

The quintessential Etruscan landscape is a panoramic view of the countryside of the Campagna or Tuscany, with an asymmetrically arranged horizon; the middle distance is not very important; the foreground offers a sense of scale and the horizon is usually fairly high. Figures are often arranged in frieze-like compositions and they remain part of the landscape; they are frequently seen at work in the countryside, or participating in more mysterious events…The format is distinctly horizontal…Many paintings represent the landscape at sunrise or dusk, with effects of light streaming obliquely. Ultimately, they represent atmospheric tonality versus colour” (Costa and Pre-Raphaelite Landscape, 94)

Costa's Dawn – Study of the Awakening of Nature, c.1883. Oil on wood; 97/8 x 32 inches (25 x 81 cm). Collection of William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, catalogue no. Br072.

Pieri further elaborated Etruscan principles: ”Costa and the Etruscans went back to the same spot year after year. They painted the same views at different times of the year and of day in an attempt to capture the quality of the landscape and the sentiment that linked them to this location in the Italian countryside. It was an attempt to capture the subtle differences of light and atmosphere while making their initial sketches from life, in order to infuse their finished paintings with the emotional resonance of the place. The sketches function as an aide-memoir which helped the artist to recall the emotion he/she felt at the time. The sentiment of communion with nature and the spiritual connection with the landscape was only partially captured in the sketches, but essentially resided within the artist and his/her ability to render the emotional response to the places and moments captured on canvas. It is the spiritual essence of the place, the genius, loci, which is the ultimate aim of this type of landscape painting” (Costa and Howard, 302).

Christopher Newall felt much the same about the characteristics of this movement: “The quintessential Etruscan landscape consists of a panoramic view of the countryside of the Campagna, or Tuscany: distant mountains provide an asymmetrically arranged horizon; the middle distance is relatively unimportant except to link the artist’s viewpoint with the distant spaces of the landscape; the foreground offers a sense of scale and draw the eye into the composition” (36). Harrison and Newall further characterized the Estruscan School by emphasizing the importance of their plein air sketches over their finished compositions worked up in the studio:

The distinctive landscape type favoured by the Etruscans was of a pronounced horizontal format, often with the outlines of distant mountain ranges placed across the width of the composition, or with river bank or coastal plain. It had its origin in the artistic principles devised by Costa in the course of expeditions into the Roman Campagna, often in company with the English painters, George Heming Mason and Frederic Leighton, in the early 1850s. Together, they developed a technique of sketching in plein air, often on panels or on paper or card, in which they sought to convey the structure and atmospheric affect of the landscape in as direct and painterly a way as possible. These essentially private exercises served as a means of visual training, and were quite distinct from the large-scale figurative works which were painted in the studio, and which, especially in the case of Costa, could occupy them for many years at a time. [155]

Virginia Surtees has observed that in Etruscan School paintings a system was adapted in which certain basic features were observed: “The subject was to be drawn by means of spaces in the background…. In the method of interpretation the form was first planned, and this was largely governed by the extended horizontal format adopted generally by the school. Tonal quality and atmosphere followed and here the moods of nature were successfully reflected in the fall of light, sunrise and twilight in particular captured with evocative fidelity. Once accurately sketched from nature, the landscape subject, with its interest often heightened by the introduction of a building, was painted and enlarged in the studio” (131)

Members of the Etruscan School had obviously found inspiration in sketching trips into the Roman Campagna where its beauty, as well as Costa’s encouragement, acted as a stimulus for this group of artists to pursue plein-air landscape painting. Costa formulated his ideas on landscape art which he discussed with his followers:

A picture should not be painted from nature. The study which contains the sentiment, the divine inspiration, should be done from nature. And from this study the picture should be painted at home, and, if necessary, supplementary studies be made elsewhere…. Sentiment before everything. Art must express the sentiments of the artist’s own country, and its merit can be judged by the success it attains in this respect…. The difference between the Impressionist, and the followers of the Etruscan School consists in this: Impressionist do what they see without reasoning or really feeling it; the Etruscan gets his impression, and works upon it, and develops it at home, adding to the skill of his hands and the exactness of his eye judgment and feeling as to form, and the direction of colour and lines…You must always know the reason of what you are doing; work should be systematised and done in order – 1st, the construction building up of the whole; 2nd, the colour; 3rd, the atmosphere…. Above all, it is desirable to avoid that confusion which arises from putting in details before being sure of the exact value of each of the chief planes. One must proceed always, he maintained, from the masses to the details, excluding everything that does not help to express the main idea. [Agresti, Costa, 213-16]

Agresti also commented on the importance that Costa placed on technique: ”At the same time he was always keenly alive to the importance of technique; the composition of a picture is a question of sentiment; but sentiment aided by good technique is doubly powerful; and thus in all his work, both in the studies from nature and in his finished pictures, we find poetic feeling and comprehension of the essential characteristics of his subject allied to minute and accurate study and great delicacy of finish” (59-60). Although figures can often be found in Costa’s landscapes, as Agresti pointed out: “These small figures, which one is sometimes tempted to wish that he had not introduced, are characteristic of Costa’s landscapes; they are not introduced to lend a human interest, but, as Stopford Brooke says, are treated as a mere appendage to nature, or rather as one of her natural products, as much a part of her as a tree or a rock” (229).

Critical Reception of the Etruscan School

Etruscan School landscapes are not considered part of the Aesthetic Movement despite the fact that the artists associated with this movement exhibited at the principal venues for Aesthetic Movement artists the Grosvenor Gallery and the New Gallery. The figurative work by some members of this group, however, could frequently be said to belong to the Aesthetic Movement, and not just by its prominent practitioners like Leighton, Crane, and Richmond, but also members like Maclaren, Corbet, and Barclay. Certainly by the early 1870s critics were already beginning to recognize this. The reviewer for The Saturday Review in 1871 commented:

We will now turn to a pictorial phase which seems identified with the South of Italy. The aspect and the rise of this new phenomenon are exceptional. It was but the other day that certain singular products obtained a place in the Academy on sufferance, and now Gallery VII is mainly given up to the party; pictures which were used at first as foils become the ruling fashion, and a style which once provoked a smile is at length the symbol of faith, the badge of a party. The clique is numerous and compact; that it is sustained by more than common talent is at once obvious in the contributions (by the way, mostly sold) of Mr. Albert Moore, Mr. Barclay, Mr. Armstrong, Mr. Maclaren and others. This school seems identified with Italy in general, and with the island of Capri in particular. [666-67]

That same year the critic for the Art Journal made similar comments:

Certainly a large part of the pictures in Gallery VII would have been simply excluded from any exhibition in London ten or twenty years ago. And yet these eccentric works are not of a nature to pass under the term Pre-Raphaelite. In fact, since Pre-Raphaelitism has gone out of fashion a new, select, and also small school has been formed by a few choice spirits. This anomalous phrase it is not easy to define. Perhaps the school, if school it has a right to be called, can be best appreciated by examples which we owe to the talents of Mr. Moore, Mr. Maclaren, Mr. Armstrong, Mr. W. B. Morris, Mr. Barclay, and others…. The new and abnormal school we have attempted to describe has several phases; indeed, each individual artist has his distinct phase. Taken as a whole, it may be accepted as a timely protest against the vulgar naturalism, the common realism, which is applauded by the uneducated multitudes who throng our London exhibitions. [176-77]

Bibliography

Agresti, Olivia Rossetti. Giovanni Costa, his life, work, and times. London: Gay, 1907.

Cartwright, Julia. “Giovanni Costa. Patriot and Painter.” The Magazine of Art VI (1883): 24-31.

The Etruscan School. London: The Fine Art Society, 1976.

Harrison, Colin and Christopher Newall. “Giovanni Costa and The Etruscans – Painters of the Italian Landscape.” The Pre-Raphaelites and Italy. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2010. 155-182.

Newall, Christopher. The Etruscans: Painters of the Italian Landscape 1850-1900. Stoke on Trent City Museum and Art Gallery, 1989.

Pieri, Giuliana: “Nino Costa and Pre-Raphaelite Landscape.” Chapter 4 in The Influence of Pre-Raphaelitism on Fin de siècle Italy. Oxford: Maney Publishing, 2007.

Pieri, Giuliana. “Giovanni Costa and George Howard: Art, Patronage and Friendship.” The Volume of the Walpole Society LXXVI (2014): 289-307.

“The Royal Academy.” The Saturday Review XXXI (May 27, 1871): 666-67.

“The Royal Academy. Second Notice.” The Art Journal New Series X (1 June 1871): 176-77.

Surtees, Virginia. The Artist and the Autocrat. Salisbury, Wiltshire: Michael Russell Publishing Ltd., 1988.

Created 17 December 2022

Last modified 5 October 2025