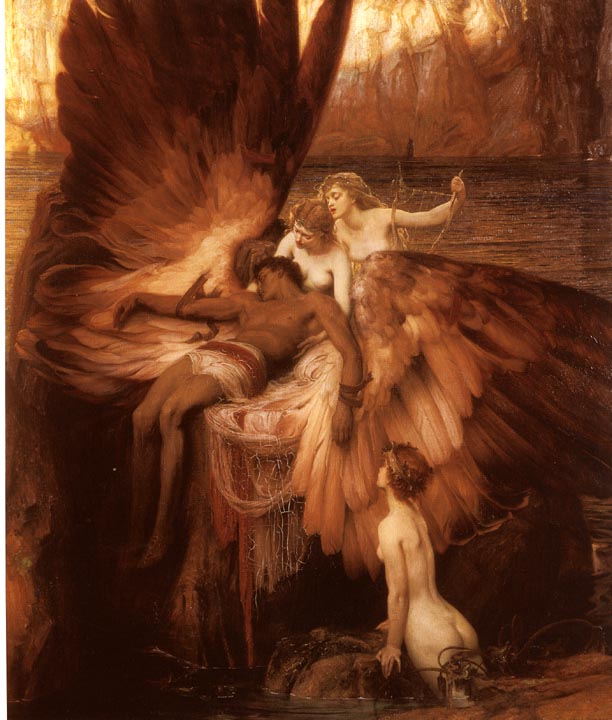

(Left) The Golden Fleece (Right) Lament for Icarus [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Simon Toll's amply-illustrated, well-written biocritical study and catalogue raisonnée goes a long way to moving Herbert Draper out of the shadows. Gaining access to unpublished letters and other manuscripts, he provides many valuable details of the painter's parents, training, painting techniques, early successes, and valuable information (in the manner of Christopher Wood's work) about models for particular pictures. He also does a good job including images of little-known painters contemporary with Draper for comparisons and otherwise placing him in the context of his time. Perhaps most important, he makes available in a single book enough images of the artist's work to begin the difficult task of making an assessment of Draper's work and artistic stature, neither of which turns out to be an easy task.

(Left) In the Studio (Right) Pot Pourri [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Part of the difficulty in assessing Draper derives from the fact that he seems an artist with many styles: in addition to the combination of Poynter and Waterhouse that characterizes major works, such as the The Golden Fleece, Lament for Icarus, and Ulysses and the Sirens, Draper paints the Watts-like allegory (or personification) of Day and the Dawnstar (see 128), the Waterhouse-like Lamia, the lovely Pot Pourri, which could have been painted by Fantin-Latour or possibly Sargeant, and the beautiful In the Studio with a pale color-range reminiscent of Albert Moore. Then, there are his portraits, some of which appear to have been painted a century earlier, which vary widely in style and success.

The one constant element in a majority of the work that the artist himself most valued lies in his superb draftmanship when representing the nude human body, male or female, particularly when matters of difficult poses or problems of perspective are involved. This volume's many reproductions of paintings and drawings repeatly demonstrate that Draper loved the unclothed human body, apparently taking equal delight in the adult male and female form which he endows with a powerful sexuality and often with what Toll correctly terms "erotic abandon" (151). His difficulty as an artist often lies in finding an adequate, appropriate subject for his nudes, too many of which, such as The Foam Sprite, The Kelpie, and The Water Nixie, seem little more than off putting, somewhat tacky pinups. According to Toll,

The first use of this motif of the ravenous feminine desire was for the The Water Nixie of 1908, a sexy enough fantasy, but not one of Draper's best pictures. The expression of the nixie is rather disturbing, and the image is uncomfortable, as the discourse between her and the beholder is so overtly sexual and predatory. Early drawings in Draper's sketchbook depict the nixie seducing a young man (and in one case, a satyr) amid the reeds. The nixie in the painting directs her attention to the spectator. [134]

I fully agree that this erotic fantasy, which to me resembles a Flint or Vargas pinup, is not one of the artist's best works and that the image (or the experience of viewing it) is "uncomfortable," but nothing of "ravenous feminine desire" or a "predatory" relationship comes across. Rudolph Arnehim long ago pointed out how test subjects project vastly different interpretations of mood and attitude upon the same picture according to verbal context, and I believe that Toll's reading of the picture exemplifies his forcing things to fit his emphasis upon the predatory-woman theme. Certainly, when I showed the image to several people, including my wife, sometimes without providing a title, no one perceived the nude figure as predatory, though all perceived this as an eroticized image, one in which the male spectator is the potentially predatory one.

I fully agree that this erotic fantasy, which to me resembles a Flint or Vargas pinup, is not one of the artist's best works and that the image (or the experience of viewing it) is "uncomfortable," but nothing of "ravenous feminine desire" or a "predatory" relationship comes across. Rudolph Arnehim long ago pointed out how test subjects project vastly different interpretations of mood and attitude upon the same picture according to verbal context, and I believe that Toll's reading of the picture exemplifies his forcing things to fit his emphasis upon the predatory-woman theme. Certainly, when I showed the image to several people, including my wife, sometimes without providing a title, no one perceived the nude figure as predatory, though all perceived this as an eroticized image, one in which the male spectator is the potentially predatory one.

Another difficulty in judging him as an artist — in addition to his frequent lapses into bad taste — are the color plates in this volume, because, not having had to opportunity to see The Kelpie and Halcyone, I cannot tell if these cold, off putting blue images so different from Pot Pourri or The Golden Fleece, accurately represent the originals. (Like many another writer on art, I have had the experience of having been betrayed by printers who failed to make required color corrections and thus produced very misleading reproductions. Did that happen here?)

Throughout his bio-critical study Toll offers many astute observations, pointing out in relation to Flying Fish, for example, that Draper "favoured depictions of women either propelled by water or floating on clouds of air, thus elevating them from the mundane triviality of dry land and casting them into the mysterious darkness of the ocean and the spectral heavens" (151). Of course, such as description doesn't fit any of his major works, with the exception what is probably his masterwork, the Draper's Hall ceiling. Nonetheless, when all is said and done, Draper and his career remain somewhat mysterious. Toll narrates the young man's confused early love life when he courted two women at the same time and tells us about later attachments, including a possible affair with a model, but we receive little detail about his marriage to Ida other than that

A photograph contemporary with Draper's portrait of Ida and Autumn shows Ida to be handsome, with the fine, if not delicate, features which Draper often found attractive in models. She retained her looks even into old age and was intelligent, refined, and sociable, sharing a good sense of humour with her husband. According to their daughter, Ida and Herbert's marriage was very happy and it seems that Draper put previous complications behind him. [88]

Before rereading Herbert Draper I had just completed going through Veronica Franklin Gould's massive, not to say ponderous, biography of G. F Watts, which contains so much about the relation between the painter and his wife. I longed for more information about the Drapers' relationship for two reasons, the first of which is that, as Toll frequently emphasizes at length, many of Draper's most important works depict devouring, sexually predatory women. Second, Toll points out the likelihood of Ida having posed for Autumn and presents side-by-side her photograph and the beautiful figure study, which certainly seems to have her face and hair. "If Ida was the model for this picture, it certainly would have been one of the most erotic pictures of a artist's wife ever painted" (88). Given the centrality of both the painter's delight in the erotic and his repeated use of themes of devouring sexuality, one needs to know more here — but the problem may well be that no reliable information exists, and, like most biographers, Toll remains somewhat dependent upon the goodwill of his subject's family. It's also particularly unfortunate that Toll was unable to reproduce the finished painting.

Another mystery lies in Draper's failure, despite his major early success and friendship with members of the Royal Academy, to gain election to that institution. Toll makes a game, if not entirely convincing, attempt tat an explanation:

Few artists became academicians until they were middle-aged, and by the time Draper was old enough to be regarded as 'established', Poynter was President. Edward Poynter was notoriously easily offended. It is possible that Poynter felt threatened by the similarity of Draper's pictures to his own. It is probably not a coincidence that no other artists in a similar style to Poynter became Associates during his Presidency. . . On 27 February 1920 Draper's name was again proposed by Frank Dicksee who became the president four years later. The Committee refused Draper's election (perhaps in respect for Poynter) and the artists Short, Tuke and Blomfield renominated him a few days later to no avail. There was nothing more that his friends could do for him. [167]

Yes, Draper may have offended Poynter and other members of the Academy, but, unlike Toll, I don't find his works all that similar to Poynter's or that he could have been perceived as a threat to the more established man. Although he draws upon Greek and Roman mythology or his major works, Draper is anything but a classical painter: impassioned to the point of grotesquerie, captured in mid-action, his figures show no interest in the classical balance and calm we find in Leighton and Poynter (an exception perhaps being the latter's The Catapult).

A good test both of Toll's claim that Draper is in some sense enough of a classical painter to threaten Poynter and of his interpretative emphasis upon the predatory female appears in The Gates of Dawn, which may also contribute to an explanation of the artist's failure to gain admission to the Royal Academy. Toll, who believes that this painting contains "one of Draper's most monumental figures," points out that artist "preferred to paint Greek legends, but in this case he painted Florrie Bird as Aurora, the Roman Goddess of the Dawn," and he speculates that Ovid's description of Eos (the equivalent Greek goddess) may have inspired the artist's treatment of the subject: "far in the crimsoning cast wakeful Dawn threw wide the shining doors of her rosefilled chambers" (101).

According to Toll, The Gates of Dawn, which at first glance appears to portray a proud, though thoughtful beauty, conveys Draper's fascination, even obsession, with destructive female sexuality:

A good test both of Toll's claim that Draper is in some sense enough of a classical painter to threaten Poynter and of his interpretative emphasis upon the predatory female appears in The Gates of Dawn, which may also contribute to an explanation of the artist's failure to gain admission to the Royal Academy. Toll, who believes that this painting contains "one of Draper's most monumental figures," points out that artist "preferred to paint Greek legends, but in this case he painted Florrie Bird as Aurora, the Roman Goddess of the Dawn," and he speculates that Ovid's description of Eos (the equivalent Greek goddess) may have inspired the artist's treatment of the subject: "far in the crimsoning cast wakeful Dawn threw wide the shining doors of her rosefilled chambers" (101).

According to Toll, The Gates of Dawn, which at first glance appears to portray a proud, though thoughtful beauty, conveys Draper's fascination, even obsession, with destructive female sexuality:

Aurora is inviting and alluring, magnificently beautiful and proud, but she is also divinely powerful. Punished by Aphrodite for enticing Ares, Aurora was condemned to be restless and destructive in her pursuit of young men. In future years Draper considered painting a scene from the story of Aurora's love for Tithonus, a mortal granted immortality without eternal youth, metamorphosed into a grasshopper after his beauty faded. The discarded roses that litter die floor at Aurora's feet refer to her inexhaustible passion, and the parasitic bindweed flowers in her hair also allude to her strangling, obsessive desire. She is like the sirens: beautiful, erotic, insatiably voracious, and never able to live happily in the company of men. Aurora was even prepared to hypnotise and rape her lovers as they slept to satisfy her sexual hunger. Draper's femmes fatales simultaneously solicit and repel, entice and caution, desire and despise. [101]

If Toll has evidence from the artist's notes or records of his conversations, the artist could well have meant the painting to mean that, but roses can mean many things, including the obvious: roses, like the dawn, have a fragile evanescent beauty . . . but return in the cycle of time. Yes, she could be looking for her next victim, but she could also be looking towards the new day, since she is, after all, the dawn. Like his handling of The Water Nixie, this passage seems forced and unconvincing.

One also has to point out that however magnificently sexual Aurora appears, she hardly seems "monumental" — at least if by that one means Draper has portrayed her with the calm and balance found in The Knidian Aphrodite or the Aphrodite of Melos — or paintings by Leighton. Unlike therm, Aurora stands with most of her weight on her right (or rear) foot, and her arms provide balance by resting against the dates of dawn. More important, The Gates of Dawn presents an extraordinarily sexualized female figure, an effect created both by the sway in her body and the painter's emphasis upon Aurora's lush, curving belly beneath which the fabric covering her hips threatens to fall, leaving her completely nude. Can it be that one reason Poynter and the other academicians did not want Draper to join them lies in precisely Draper's very-unclassical overtly erotic paintings. Lovely as the The Gates of Dawn may be, it can be taken as a semi-nude portrait of the lovely — and easily identifiable — Florrie Bird, a popular model.

What ever few questions Toll has left unanswered, he has provided a major, pioneering study of an artist who had the bad luck to have been born slightly out of his time. Toll's book, I am sure, has moved an often fascinating artist out of the shadows and at least on the edge of the limelight.

References

Toll, Simon. Herbert Draper, 1863-1920: A Life Study. Woodbridge, England: Antique Collector's Club, 2003.

Last modified 5 April 2007