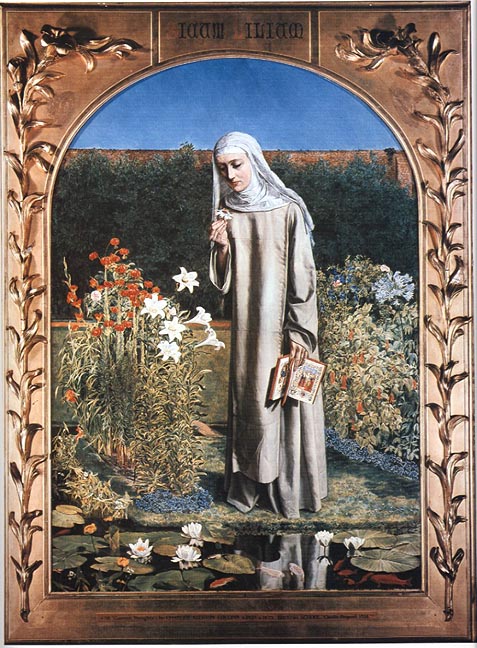

Convent Thoughts by Charles Allston Collins. (1828-1873). 1851. Oil on canvas. Arched top, 33 1/8 x 23 1/4 inches. Collection: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Compare Collins's study for the painting. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

According to Christopher Wood, "Collins's picture is typical of the early, gothic phase of the movement, and the religious piety of these works led many critics to accuse the painters of being Roman Catholic sympathizers. The mood of this picture is generally similar to Rossetti's early works, but the flowers and garden reflect Millais's influence" (22).

Peter Nahum explains that "Frances Sarah Ludlow was the beautiful model for the nun who is so delicately portrayed in this painting. The competition for stunning models was revealed by Millais in a letter to Mrs Combe on 15th January, 1851: "I saw Carlo last night, who has been very lucky in persuading a very beautiful young lady to sit for the head of the nun. She was at his house when I called, and I also endeavoured to obtain a sitting, but was unfortunate as she leaves London next Saturday" (qtd. in Faberman 66, from Millais' Life and Letters I: 94). About the same time Collins wrote to Holman Hunt mentioning that he had been working on the nun's face from "a friend of a friend" at her own house. Collins had borrowed the same nun's costume that Holman Hunt had used in Claudio and Isabella. Preparatory studies for Convent Thoughts are in the Ashmolean and the British Museum. A later version in pen and ink, dated 1853, is in Tate Britain."

Commentary by Dennis T. Lanigan

This is Collins's best-known picture and one of the masterpieces of the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851, no. 493. In the catalogue two quotations followed the painting's title. The first was taken from Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream: "Thrice-blessed they, that master so their blood / To undergo such maiden pilgrimage." The second comes from Psalms 143,5: "I mediate on all thy works; I muse on the works of thy hands."

Inception

Collins began this painting in June 1850 when he and John Everett Millais were staying at a cottage at Botley, near Oxford. Millais was initially working on his painting The Woodman's Daughter and then later on Mariana. It was at this time the two artists were introduced to Thomas Combe, the superintendent of the Clarendon Press, and a supporter of the Oxford Movement. Led by Oxford dons, such as Edward Pusey, John Keble, Richard Hurrell Froude and John Henry Newman, from 1835 through the 1850s Anglican religious leaders attempted to restore High Church ideals and rituals to the Church of England. It was the efforts of the Oxford Movement that resulted in the restoration of religious orders for women in the Anglican church. Pusey advocated that such sisterhoods should undertake useful works in hospitals, prisons, mental asylums, and homes for fallen women [Magdalen homes].

In the late summer and autumn of 1850 the Combes invited Collins and Millais to stay with them at their home in Oxford and both artists remained there until they left on November 12, 1850. Preliminary drawings by Collins in the British Museum show that he had initially intended his picture to be a secular one, illustrating the poem "The Sensitive Plant" by P. B. Shelley, but later he changed the female figure into a nun. The background for Convent Thoughts was therefore painted some time prior to adding the figure of a nun in religious contemplation. The nun's costume was borrowed from Holman Hunt and was the same one used by Hunt in his painting of Claudio and Isabella. The flowers were all painted from nature in the garden of Thomas Combe's home in the quadrangle of the Clarendon Press in Oxford. The flowers in the painting symbolise various traits of a nun in the language of flowers, including remembrance (Forget-me-nots), purity (Madonna lilies), constancy (Evergreen trumpet honeysuckle) and the most important of all the passion for Christ (the Passion flower). The background for the picture was painted very much under Millais's influence and guidance (Warner 87). Rupert Maas has noted about Collins's painting and Millais's Mariana, also exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851: "Both Mariana and Convent Thoughts are about seclusion, the former by abandonment and the latter by choice" (6). The background of Collins's picture was painted in minute detail consistent with the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. Combe remembered the painstaking work of Collins painting it: "He worked very slowly, and I know that a flower of one of the lilies occupied a whole day" (qtd. in Warner 87). According to Anne Neale, Collins was the first Pre-Raphaelite artist to demonstrate that "medievalism and naturalism could be successfully integrated in a modern work" (93).

Liz Prettejohn has further expanded on this concept:

"Collins's Convent Thoughts offers a visual demonstration of the parallel between ancient and modern Pre-Raphaelitism. The illuminated missal in the nun's hand is an example of "archaic" art. The pages that are visible show "primitive" depictions of the Crucifixions and the Annunciation. The nun has allowed the missal to drop unregarded to her side, in order to contemplate the "natural" passion flower in her hand. We might read this as symbolic of the shift in emphasis from archaism to naturalism, found in discussions of Pre-Raphaelite art, both ancient and modern at this point. But the precise delineation of the missal artist's work corresponds to the botanical specificity of the nineteenth-century artist's work, and the jewel-like colours of the illumination are echoed in the vivid hues of the garden. Even the missal's decorative borders, with their bold colours and intricate interlaced lines, seem to correspond to the luxuriant flowerbeds of the nun's garden. The picture asks us, with the nun, to compare the mediaeval artist's work with the natural beauty of the garden. [63]

Religious Context and Iconography

Collins's attraction towards asceticism and to the ritualistic aspects of High Anglicanism are obviously reflected in this work that he painted following his conversion to the Tractarian Movement. While the painting exemplifies the ideals of "truth to nature" of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, it also incorporates complex literary symbolism. Malcolm Warner has noted:

A nun, probably a novice, contemplating the crucifixion of Christ as symbolised in a passion flower – so called because of the cross shape formed by the stamens. The manuscript in her hand is open at illuminations showing the crucifixion and the Virgin Mary, to whom she is implicitly likened. The inscription at the top of the frame, "Sicut Lilium," is from the Song of Solomon 2.2, "Sicut lilium inter spinas" ("As the lily among thorns"), an image applied frequently to the Virgin Mary. Here it is taken up in the white lilies near the nun and (for the thorns) the roses towards the back of the flower beds. The garden also contains turk's-cap lilies, water-lilies and an African lily (agapanthus) and there are lilies on the frame, which was designed by the artist's friend Millais. The image of the "garden enclosed" or "hortus conclusus" from the Song of Solomon 4.12 is also associated with the Virgin and virginity in general and Collins may have had that in mind as well when devising the iconography of the picture. The goldfish, some red, some white, seem to echo the major themes of Christ's sacrifice and the nun's purity. [87]

The fish itself is a symbol of Christ.

The obvious religious iconography contained in this painting, and in Rossetti's painting Ecce Ancilla Domini exhibited at the National Institution in 1850, led some critics to accuse the Pre-Raphaelites of Roman Catholic sympathies. It is no surprise that the first owner of Convent Thoughts was Thomas Combe who was a strong devotee of the Oxford Movement. Combe purchased the painting under its alternative title Sicut Lilium for £150, which was the highest sum Collins ever received for a picture. It appears, however, the Combes bought the picture more to help Collins than because they particularly liked the painting. In a letter of 28 May 1851 from Millais to Martha Combe he writes: "I cannot help believing, from the evident good feeling evinced in your letter, that you have thought more of the beneficial results the purchase may occasion him than of your personal gratification at possessing the picture" (Millais I: 103).

Alison Smith has pointed out the associations in the painting between the nun, likely a novice, and the Virgin Mary:

The picture represents a nun in an enclosed garden contemplating the stamen of a passion flower, an emblem of the Crucifixion. This connection is suggested by the Book of Hours she holds in her left hand, which is shown open at a page emblazoned with an image of Christ on the cross surrounded on three sides by the Virgin, St John and Mary Magdalene. The page she has actually been studying, which is marked by her index finger, discloses an image of the Annunciation. Ideas associated with this event are developed within the painting itself through the image of the lily, a standard attribute of the Virgin Mary. Through a sequence of registers of verisimilitude, the eye is led from the representation of the Annunciation in the book to the painted lilies in the garden, and the three-dimensional blooms on the frame, which was designed like that of The Return of the Dove by Millais. The Latin description at the top, Sicut lilium ("as the lily among thorns"), taken from a passage in the Song of Solomon, reinforces the association between the nun and the Virgin and the former's vocation in a celibate cloistered existence. The theme of virginity would have been further acknowledged by the quotation from A Midsummer Night's Dream that accompanied the painting when it was first shown at the RA in 1851: "Thrice blessed they, that master so their blood / To undergo such a maiden pilgrimage." [121]

The Frame and Compositional Elements

The frame was thus an artistic collaboration between Collins and Millais. On April 11, 1851 Millais wrote to Thomas Combe: "I have designed a frame for Charles' painting of 'Lilies' which, I expect, will be acknowledged to be the best frame in England" (Millais I: 100). It features a single stem of Madonna lilies in high relief at each side and was inscribed "Sicut Lilium" at the top. The illuminator and botanical illustrator Edward La Trobe Bateman had suggested to Millais the medieval-style script and the naturalistic flowers as narrow vertical manuscripts.

Smith goes on to point out the importance of the late fifteenth century Italian Book of Hours held by the nun:

"The manuscript that Collins adapted from a missal in the Soane Museum would seem to provide the key to the composition. What we see in miniature form on the open page – a bordered hieratic scene surrounded by a decorative margin - is reinterpreted in the main body of the composition in the image of a nun encased within her shapeless habit, isolated on a grassy island, and hemmed in on either side by carefully aligned areas of brilliantly coloured foliage. Collins was well known among the pre-Raphaelites for his High Church sympathies, and the "Catholic" elements of his picture would not have been lost on his audience at a time when the revival of secluded orders was a subject of intense debate within the established church. [121]

Julian Treuherz has discussed the topical nature in Tractarian circles of such a nun as portrayed in Collins's picture: "In the six years before 1851, when it was exhibited, six communities of nuns had been founded within the Church of England, the first since the Reformation. The earliest was a Puseyite sisterhood which opened in 1845 at 17 Park Village West, across Regent's Park from Hanover Terrace where Collins lived. In 1848 the sisters moved to Albany Street and worshipped at Christ Church, Albany Street, also attended by the Rossetti family" (157). In 1874, at the age of forty-six, Maria Rossetti joined the Society of All Saints, an Anglican order for women.

Susan Casteras has discussed the transformation of the painting from Collins's original idea of illustrating Shelley's "The Sensitive Plant" into a postulant contemplating a passion flower and holding a Bible:

"In the final work, which was at first entitled Sicut Lilium, the young woman wears the light grey habit and white wimple of a postulant, perhaps that of a Poor Clare; her garb indicates that she is probably not yet taken her final vows. This 1851 Royal Academy entry was accompanied by several lines chosen by the artist from both A Midsummer Night's Dream and the Bible – 'I meditate on all thy work; I muse on the work of Thy hands' (Psalms 113:5). Using this biblical allusion, Collins places a Madonna-like figure amidst virginal lilies as she meditates on God's work – her physical surroundings – in this modern hortus conclusus, or enclosed garden of chastity. The rose with thorns growing in this garden contrasts implicitly with the thornless Virgin, who was exempt from the consequences of original sin. The sombre postulant marks two places in her missal with her fingers: one is an image of the crucified Christ, the Holy Bridegroom to whom she is now promised, and the other is a scene of the Nativity, perhaps an allusion to the role of mother and wife which she has spurned by electing to become a sister. As with other representations of this type, the young woman is isolated from the outside world in a religious inner sanctum, bordered by a high brick wall that restricts her sphere of action and forcibly closes out all reminders of the past. The artist uses several goldfish and tadpoles in the pool on this tiny island of chastity to contrast their procreative state with the young woman's virginity. The beautiful blossoms of agapanthus, lobelia, fuchsia, and other flowers similarly confirm the luxuriant, colorful vitality of nature, thus reiterating the contrast between the setting's bountiful lushness and the woman's austere garments and existence" (171-72).

Casteras has possibly identified the order to which the young nun belonged:

The novice in Collins's painting may have been a member of the Society of the Holy and Undivided Trinity at Oxford, which was where the artist created the work and might have seen or known of the sisterhood. Grey robes were worn in other Anglican nunneries, but light grey seems to have been reserved for probationary stages at Oxford and elsewhere. The sister who had taken final vows was more likely to wear a habit of darker grey or even black. [170, n.27]

The Model

Who modelled for the face of the nun in Convent Thoughts is controversial. The face of the nun has always thought to have been modelled from Frances Sarah Ludlow, a maid in the Oxford household of Thomas Combe (Faberman 66). More recently, however, Susan Haines has suggested that the face was instead modelled from her great-grandmother, Sarah Eliza Hackett (Haines 23). Sarah Hackett was born in 1832, the daughter of a farmer in Diseworth, Leicestershire, where she spent her formative years. In 1851, however, she is recorded in the census as residing in Lambeth as a visitor. Her uncle, Dr. John Thompson, lived in the Marylebone district and he was not only the family doctor to the Collins household for over twenty years but he and his family were also close friends of the Collins family. Charles Collins must have met Sarah Hackett sometime during the winter of 1850-51. On 15 January 1851 Millais wrote to Mrs. Combe: "I saw Carlo last night, who has been very lucky in persuading a very beautiful young lady to sit for the head of 'The Nun'. She was at his house when I called, and I also endeavoured to obtain a sitting, but was unfortunate, as she leaves London next Saturday" (Millais I: 94). Millais would have hardly written such a letter to Mrs. Combe if the lady in question was a maid in her own household. At about the same time, but in an undated letter, Collins wrote to Holman Hunt: "I have been very much occupied lately having taken the trouble of persuading a young lady to sit, who struck both Millais and myself as having possessed a very beautiful head – she was a friend of a friend of mine so after some trouble I managed to secure her, but I have been obliged to hurry very much as her time was limited. I had to pursue her to her own house and take sittings there, getting up very early for this purpose" (Haines 25-26). The fact that the model is referred to in the letters as a young "lady" makes it much more likely that Collins and Millais are referring to Sarah Hackett than to Frances Ludlow, who was a domestic servant. More evidence is contained in a letter that Sarah Hackett's married daughter Frances Burder wrote years later: "Mamma's cousin Charlie painted her as a nun just before she was married and Sir John Millais wanted to but her husband objected" (Haines 25). Sarah Hackett was soon to wed her fiancé, the Reverend Frederick Nash, who may have objected to her modelling because she was "venturing outside the parameters of social convention in modelling for one painting, let alone two…. Then, there were her duties and responsibilities as a clergyman's wife to consider and he did not want his or her reputation compromised in any way" (Haines 25-26). Unfortunately no known photograph of Sarah as a young woman survives. A family photograph of her at age 57, taken in a frontal view, shows her features are compatible with the model of the nun in Convent Thoughts (see Haines, fig. 1, 28)

Reception

When Convent Thoughts was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851 it was extensively reviewed but generally not favourably. The critic for The Art Journal recognized its Pre-Raphaelite affiliation but decried its feigned primitiveness:

No. 493. Convent Thoughts, C. Collins. A composition in the taste of the P.-R.B., representing a single figure, a nun meditating in the garden of her nunnery. The figure is excessively meagre; there seems to be nothing within the draperies, and then the head, which is disproportionally large, over balances the rest of the figure: there was never anything in nature like the effect of the potent greens of these parterres. If there be anything right in this then all art since the days of Masaccio is wrong. [158]

The reviewer for The Athenaeum, singled out Collins's painting as being the most prominent Pre-Raphaelite picture in the Royal Academy exhibition, surprisingly since both Millais and Hunt also exhibited major works:

Of the Pre-Raffaelite brethren little need now be said, - since what has been already said was said in vain. Mr. Charles Collins is this year the most prominent among this band in Convent Thoughts (493). There is an earnestness in this work worth a thousand artistic hypocrisies which insist on the true rendering of a buckle or a belt while they allow the beauties of the human form divine to be lost sight of. [609]

F. G. Stephens writing in The Critic not surprisingly praised the work and felt it showed a highly poetical imagination:

Mr. Collins's work, Convent Thoughts, No. 493, a nun in a garden, looking thoughtfully at a bloom of the passion flower. The idea suggested, which is most extremely beautiful and touching, is admirably expressed by the face of the nun. Her drapery is well painted, so is every portion of the picture, especially a pool, by which she is standing, with some water lilies in it. The flesh is also beautiful in drawing and colour. We think, however, that the right hand of the nun is a little too large, and the whole of the picture rather flat, and wanting gradation of colour and half-tint. We must not forget, in looking at this, that the subject is an invention (a most beautiful one it is), as well as the design which expresses it, and allow Mr. Collins no small credit for a highly poetical imagination. [290]

Stephens then went on to counter John Ruskin's earlier assertion that the painting exhibited a "Tractarian and Romanist" tendency, despite the fact that it obviously did:

Mr. Ruskin's letter to The Times, which was reprinted in a previous number of this journal, relating to these last mentioned pictures, calls, we think, for some remark. While allowing a very high degree of merit, he attributes a "Tractarian and Romanist tendency" to them – an assertion, we imagine, scarcely worthy of that most talented and eloquent writer, whose works have done so much to assert the true dignity and mission of art. We must, with great deference, protest against the assumption of this tendency as being found in these works, particularly as relates to the artists themselves, for we all know that our good protestant, Mr. Bull, is extremely apt to take these phrases as a portion of the red rag of Popery, and, confounding the painter with his work, to toss both into the air. Stick but these words upon a man, and, shocked and terrified, our excellent John rends up the ground, and gores at once. We do not even see that painting a nun in a convent garden (this is the only point which can possibly have connection with the remark) has necessarily a "Romanist or Tractarian tendency." No one, we fancy, will imagine her thoughts can be purely in human happiness, or that depicting such a subject is a recommendation to any young lady at the exhibition to go and do likewise. Surely there is no false sentiment or affectation in the picture, or the choice of the subject. [327]

The comments by Ruskin that Stephens refers to are found in a letter Ruskin wrote to The Times on May 13, 1851 in defense of Pre-Raphaelite artists. The pertinent part of the letter relating to Collins is:

"Let me state, in the first place, that I have no acquaintance with any of these artists, and very imperfect sympathy with them. No one who has met with any of my writings will suspect me of desiring to encourage them in their Romanist and Tractarian tendencies. I am glad to see that Mr. Millais' lady in blue is heartily tired of her painted window and idolatrous toilet table; and I have no particular respect for Mr. Collins' lady in white, because her sympathies are limited by a dead wall, or divided between some gold fish and a tadpole -(the latter Mr. Collins may, perhaps, permit me to suggest en passant, as he is already half a frog, is rather too small for his age). But I happen to have a special acquaintance with the water plant, Alisma Plantago, among which the said gold fish are swimming; and as I never saw it so thoroughly or so well drawn, I must take leave to remonstrate with you, when you say sweepingly that these men sacrifice truth as well as feeling to eccentricity. For as a mere botanical study of the water lily and Alisma, as well as of the common lily and several other garden flowers, this picture would be invaluable to me, and I heartily wish it were mine. [320-21]

In a follow up letter to The Times of May 30, 1851 Ruskin writes:

I do not think I can go much further in fault-finding. I had, indeed, something to urge respecting what I supposed to be the Romanizing tendencies of the painters; but I have received a letter assuring me that I was wrong in attributing to them anything of the kind; whereupon, all I can say is that, instead of the "pilgrimage" of Mr. Collins' maiden over a plank and round a fish-pond, that old pilgrimage of Christiana and her children towards the place where they should "look the Fountain of Mercy in the face," would have been more to the purpose in these times. [327]

The reference to Christina and her children comes from John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Part two.

One of the most scathing reviews of the painting came, not surprisingly, from the pages of Punch, well known for its anti-Catholic sentiments:

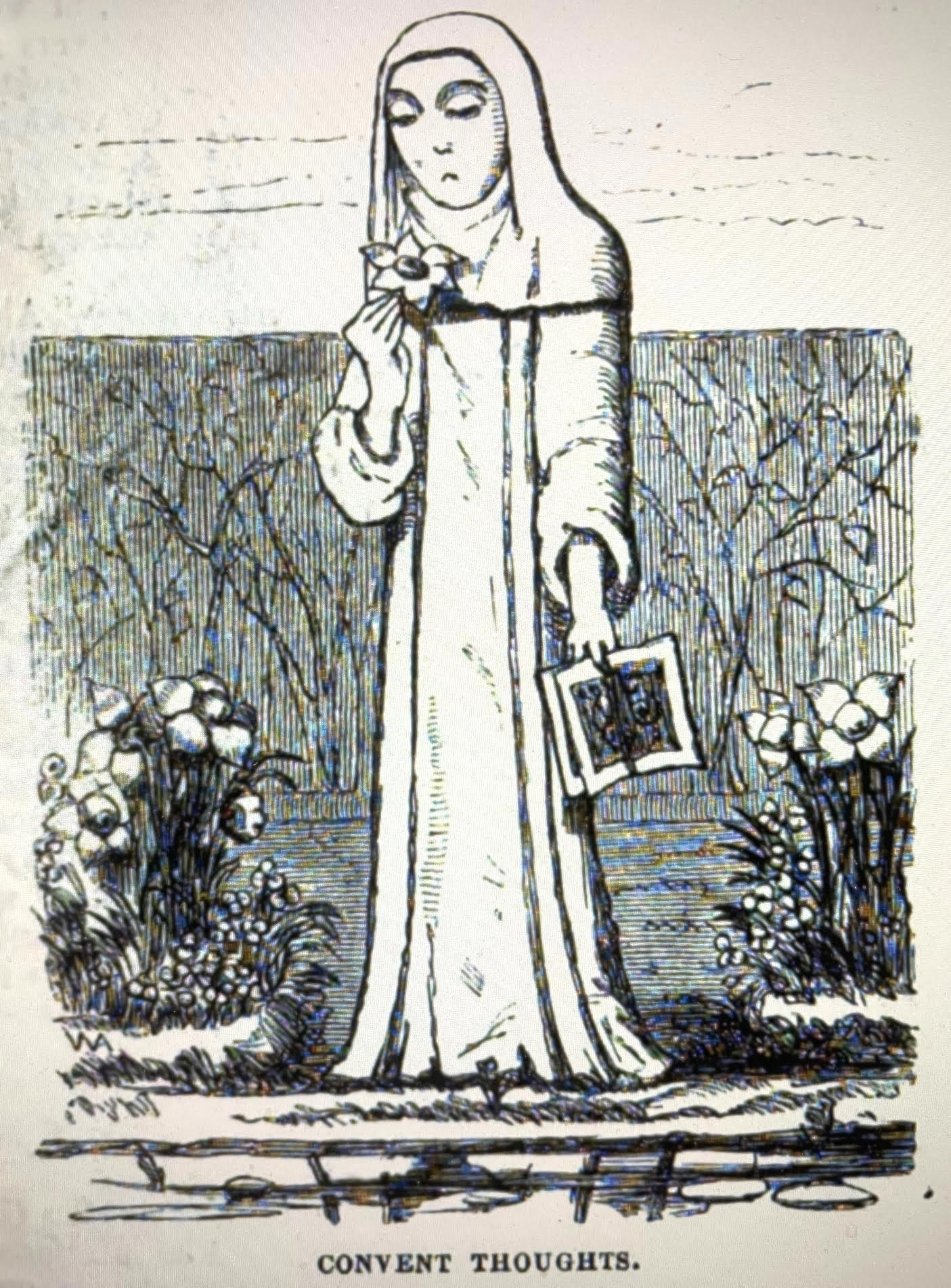

"Our dear and promising young friends, the Pre-Raphaelites, deserve especial commendation for the courage with which they have dared to tell some most disagreeable truths on their canvases of this year. Mr. Ruskin was quite right in taking up the cudgels against the Times on this matter. The pictures of the P.R.B. are true, and that's the worst of them. Nothing can be more wonderful than the truth of Collins's representations of the "Alisma Plantago," except the unattractiveness of the demure lady, whose botanical pursuits he has recorded under the name of Convent Thoughts. Whether by the passion-flower he has put into her hand, he meant to symbolise the passion which Messrs. Lacey, Drummond, and Spooner are inspired against the conventual life, or the passion the young lady is in with herself, at having shut up a heart and life capable of love and charity, and good works, and wifely and motherly affections and duties, within that brick wall at her back – whether the flower regarded and the book turned aside from, are meant to imply that the life of nature is a better study than the legend of a saint, and that, therefore, the nun makes a mistake when she shuts herself up in her cloister, we are not sufficiently acquainted with Mr. Collins's ways of thinking to say. By the size of the lady's head he no doubt meant to imply her vast capacity of brains – while by the utter absence of form and limb under the robe, he subtilely conveys that she has given up all thoughts of making a figure in the world" (219).

Left: The painting without its frame. Right: "Convent Thoughts" in Punch XX (1851): 219.

Wilkie Collins writing anonymously in Bentley's Miscellany discussed extensively the works of the Pre-Raphaelite painters in the exhibition including that of his brother:

"Mr. Collins's picture, in the Middle Room, is entitled Convent Thoughts and represents a novice standing in a convent garden, with a passion-flower, which she is contemplating, in one hand, and an Illuminated missal, open at the crucifixion, in the other. The various flowers and the water-plants in the foreground are painted with the most astonishing, minuteness and fidelity to nature – we have all the fibres in a leaf, all the faintest varieties of bloom in a flower, followed through every gradation. The sentiment conveyed by the figure of the novice is hinted at, rather than developed, with deep poetic feeling – she is pure, thoughtful, and subdued, almost to severity. Briefly, this picture is one which appeals, in its purpose and conception, only to the more refined order of minds – the general spectator will probably discover little more in it, than dexterity and manipulation. [623-24]

Collins then goes on to write further, after discussing paintings by Millais and Hunt:

Such are some of the most prominent peculiarities of these pictures which come within the limits of so brief a notice as this. If we were to characterize, and distinguish between, the three artists who have produced them, in a few words, we should say that Mr. Collins was the superior in refinement, Mr. Millais in brilliancy, and Mr. Hunt in dramatic power. The faults of these painters are common to all three. Their strict attention to detail precludes, at present, any attainment of harmony and singleness of effect. They must be admired bit by bit, as we have reviewed them, or not admired at all. Again, they appear to us to be wanting in one great desideratum of all art – judgment in selection. For instance, all the lines and shapes in Mr. Collins's convent garden are as straight and formal as possible; but why should he have selected such a garden for representation? Would he have painted less truly and carefully, if he had painted a garden in which some of the accidental sinuosities of nature were left untouched by the gardener's sped and shears?... We offer these observations in no hostile spirit: we believe that Messers Millais, Collins, and Hunt, have in them the material of painters of first-rate ability. [624]

Two very early studies for Convent Thoughts are at the British Museum. A preliminary sketch for the composition, dated 1851, is at the Ashmolean Museum and a copy of this drawing, dated 1853, is at Tate Britain.

Related Material

- Study for Convent Thoughts in the British Museum

- Study after Convent Thoughts at Tate Britain

- Women's Religious Orders in Victorian England

- The Conventual Life and Victorian Culture

- Reverie and the Contemplative Woman

- On Process and Persistence: Visions of Time in Pre-Raphaelite and Decadent Works

Bibliography

Al-Maliky, Saad Mohammed Kadhum. Charles Allston Collins's Paintings of 1850s. University of Basrah, College of Education for Human Sciences, Department of English, 17-19. https://faculty.uobasrah.edu.iq/uploads/publications/1709056417.pdf

Casteras, Susan P. "Virgin Vows: The Early Victorian Artists' Portrayal of Nuns and Novices." Victorian Studies XXIV, No. 2 (Winter 1981): 157-84.

Collins, Wilkie. "The Exhibition of the Royal Academy." Bentley's Miscellany XXIX (June 1851): 617-627.

Faberman, Hiliarie: The Substance or the Shadow: Images of Victorian Womanhood. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1982. 66.

Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1232 (7 June 1851): 608-10.

Haines, Susan: "Sarah Eliza Hackett: Fresh Research Places Her as the Model for the Novice in Convent Thoughts." The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society XXI, No. 2. (Summer 2013): 23-30.

Hallett, Mark and Sarah Victoria Turner Eds. The Great Spectacle: 250 years of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2018. 86.

Hewison, Robert, Ian Warrell and Stephen Wildman. Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Publishing, 2000, cat. 9, 35.

Maas, Rupert. "The life of Charles Allston Collins (1828-73): and his painting The Devout Childhood of St Elizabeth of Hungary." The British Art Journal XV, No. 3 (Spring 2015): 41-42.

Meisel, Martin. "Fraternity and Anxiety: Charles Allston Collins and the Electric Telegraph." Notebooks in Cultural Analysis. Two Vols. Eds. Norman F. Cantor and Nathalia King. Durham: Duke University Press, 1985, Vol. II: 112-168.

Millais, John Guille. The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais. Two Volumes. New York: Frederick A Stokes Company, 1899.

Neale, Anne. "Considering the lilies: Symbolism and revelation in Convent Thoughts (1851) by Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873)." The British Art Journal XI (2010): 93-99.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

"Punch Among the Painters." Punch XX (1851): 219.

Somerset, Douglas. "The Models for Convent Thoughts. The PRS Review. XXIX, No. 2 (Summer 2021): 46-50.

Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin. Eds. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. London: George Allen, 1904. Vol. XII: 320-21 & 327.

Smith Alison. "Convent Thoughts." Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde London: Tate Publishing, 2012. 121.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Critic X (June 14, 1851): 289-90

The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series III (June 1, 1851): 153-163.

Treuherz, Julian. "The Pre-Raphaelites and Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts." Pre-Raphaelite Papers. Ed. Leslie Parris London: The Tate Gallery / Allen Lane, 1984. 153-69.

Last modified 14 September 2024 (commentary added)