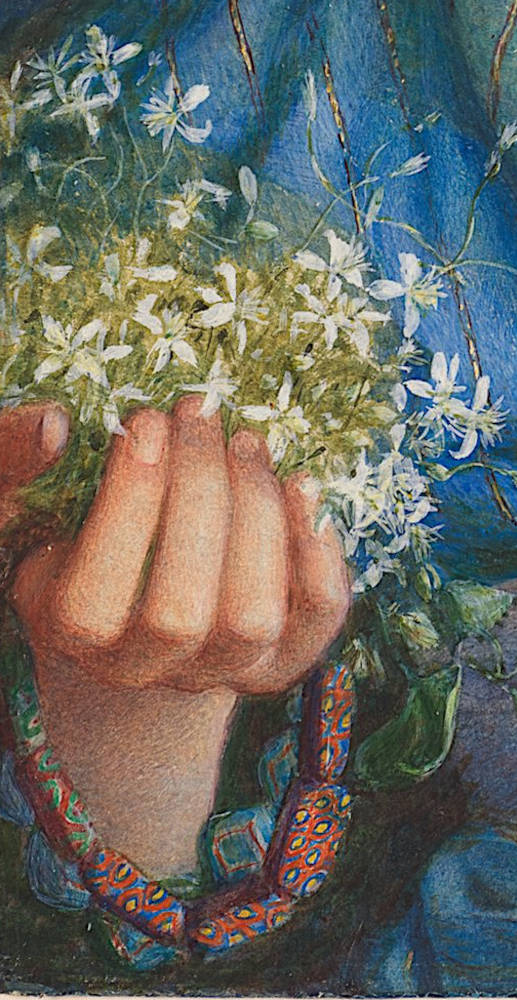

Clematis. Frederic William Burton. Watercolour and gouache on card, 13 15/16 x 10 ½ inches (35.4 x 26.4 cm). Collection of Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, object no. 1943.484.n.

This work that Burton exhibited at the O.W.S. in 1865 appears to be a variant of The Child Miranda that he had exhibited the year previously and utilizing the same child model. Her head and torso are in the exact same position but he has modified the position of the arms and hands and changed her costume to an exotic fabric of pale blue with golden stripes. Her left arm is held upright, with her hand behind her head, and appears awkwardly handled for so able a draughtsman. Burton has changed the direction of the lighting and the backgrounds are different as well, with this time it largely featuring a green fabric rather than green foliage and passion flowers. The picture is entitled Clematis for the bouquet of tiny white clematis flowers she holds in her right hand. This is very much a subjectless “Aesthetic picture” dependent for its success on formal and decorative values rather than telling a story like most Victorian genre paintings. The clematis flowers may have been included for symbolic not just decorative purposes. These flowers can convey various symbolic meanings including travelers joy, wisdom, and mental prowess.

Left: The Child Miranda. Middle: The Climatis Flowers. Right: The child’s hair (right). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The critic of The Art Journal had these comments on the picture: “Mr. Burton, we are sorry to say, shows some falling away from his former high estate. Of the two drawings he has executed, ‘Clematis’ (247), a small and careful study of a single head, is the best. Here is a little girl, ‘Clematis’ flower in hand, with rose in the cheek, gold in the hair, and green of contrasted harmony in the robe, colours which compose into a subject altogether charming” (174). F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum recognized the similarity of this work to his exhibit of the year previously and that the left arm was not well drawn: “Clematis (247) shows what we saw before here, - a young girl with one arm that is not well drawn, behind her head; the face is tender in expression, soft and clear, and well drawn” (593). The reviewer of The Illustrated London News compared this unfavourably to The Child Miranda: “Clematis (247), a smaller drawing, by the same artist, of a girl holding a tangled branch of the pretty creeper, is more to our taste, though rather heavy (particularly the hair), and not to be compared to a former drawing of a similar subject” (410).

This watercolour was again influenced by the Venetian-inspired works by D. G. Rossetti and his circle in the 1860s. In this case Frederick Sandys in particular comes to mind in works such as Mary Magdalene of c. 1859, King Pelles’ Daughter bearing the vessel of the Sangrael of 1861, and May Margaret of 1865-66. Certainly Frederick Sandys and Burton were well acquainted and friends by 1866 if not earlier and Burton would have seen the works that Sandys had exhibited at the Royal Academy.

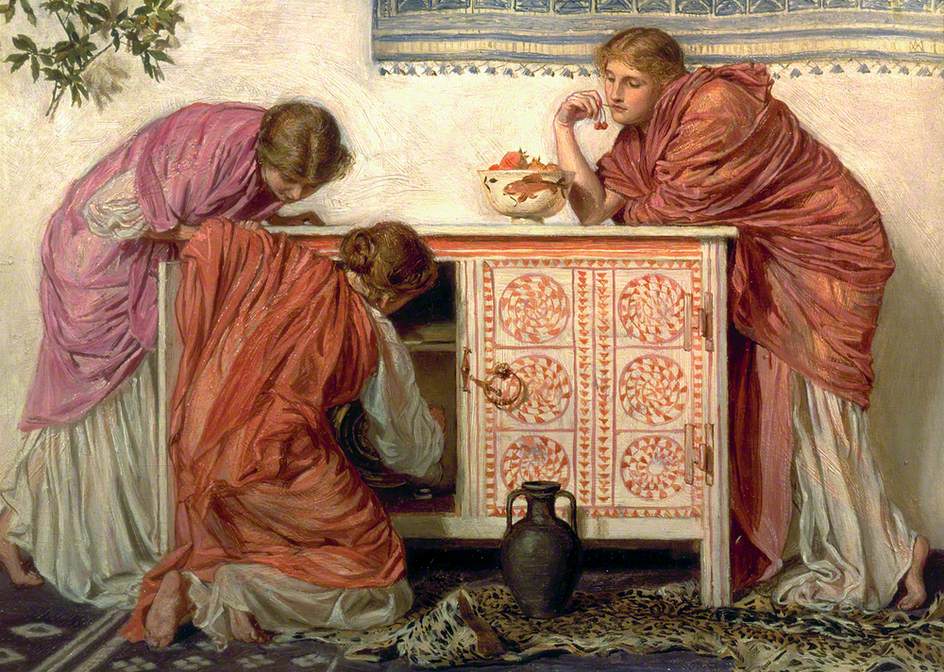

Naming the composition after one of the accessories, in this case flowers, and also using an almost identical composition but modifying the colour harmonies and accessories is reminiscent of the later practice of Albert Moore starting in the 1860s.

Three paintings by Albert Moore. Left: Pomegranates. Middle: White Hydrangeas. Right: Anemones.

Examples of Moore naming paintings after accessories would include Pomegranates of 1865-66, Apricots of 1866, and Azaleas of 1867-68. Instances where Moore used the same identical composition but changed the colour harmonies and/or accessories would include Beads, Apples, and A Sofa, all of 1875.

Frederic Leighton also produced similar examples of fancy portraits of young girls, particularly Italian models, such as Catarina or Neruccia. For many years this watercolour was attributed to J. E. Millais on the basis of a fake Millais monogram in the upper right. This must have been added very early on as the work had been bequeathed to Harvard by famed collector Grenville L. Winthrop in 1943. It is not surprising that this attribution was accepted for so long because Burton’s work would have been long forgotten at that time and Millais, of course, was famous for his portraits of children.

Bibliography

“The Society of Painters in Water Colours.” The Art Journal, (1865): 173-75.

Stephens, Frederic George. “Society of Painters in Water Colours.” The Athenaeum no. 1957 (April 19, 1865): 593-94.

“Fine Arts. Exhibition of the Society of Painters in Water Colours.” The Illustrated London News 46 (April 29, 1865): 410-11.

Last modified 11 April 2022