The following essay comes from the Studio, No. 244 (June 1917): 149-160. The accompanying illustration have been added as close as possible to their place in the original text. In just one case (the first view of Bosham, Sussex), a colour version from one of Ball's own books has been exchanged for the black and white one in the text. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Portrait photograph by an unknown photographer.

Source: Hind 149.

CLOSE my eyes, dream back a quarter of a century, and out of the mist of memory comes Wilfrid Ball, quick of step, quick of smile, quick of comprehension, more vivid to me than many of the living. Those were the days of the old Hogarth Club, and regularly, when he was in London, he would descend from his spacious sky studio in Albemarle Street to lunch and dine at the Hogarth. His habits were methodical. Early training as an accountant had taught him method. His mind, too, was orderly. Revolutionary art, revolutionary opinions, did not interest him. His pleasure and duty was to produce Wilfrid Ball Water-Colours. On that he concentrated. He loved painting; he loved etching; he loved nature, and he was quite content to march modestly along the pleasant road of his pleasant choice. I do not think that he was in the least ambitious, and I am sure that he had no vanity, and no illusions about himself. He liked to etch and to paint, and he was delighted to find that art dealers and the public also liked his water-colours and etchings. For years Agnew's showed a panel of Wilfrid Balls at their annual water-colour display. He was successful. In a quiet way his work was in greater demand than the performances of men with a much greater reputation.

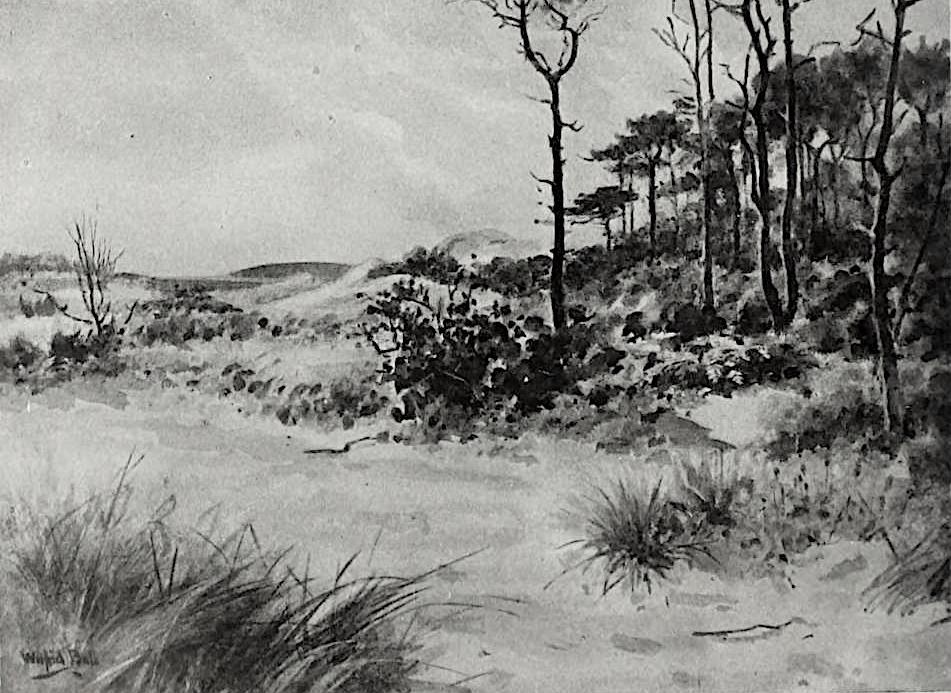

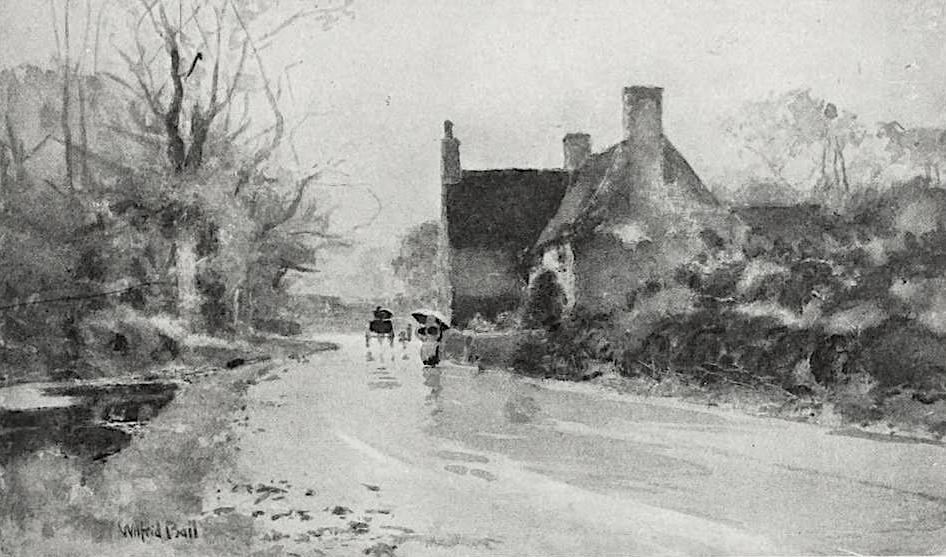

Left: View at Bosham, Sussex. Source: Ball, Sussex, 140. Right: A Path in the New Forest, by courtesy of Arthur R. More, Esq. Source: Hind 151.

The explanation is simple. His patrons were not professional buyers. They bought his water-colours because they liked them, liked to hang them in their drawing-rooms. A Beardsley would have been provocative; a Ball was sedative. His patrons were wide-cast and faithful. Last week when I asked a bank manager of my acquaintance, who spends his Sundays painting in water-colour, if he knew Wilfrid Ball's work, he smiled and invited me into his home. I counted over twenty Wilfrid Balls in various rooms. And Mr. Deighton, a lifelong friend and patron, tells me that for years he had only to put a Wilfrid Ball into his window to sell it immediately. They were not bought by les jeunes, or by those who scramble for fine Brabazons>; they were bought by the solid, family English who never change. (How [149-50] Wilfrid would have laughed at all this: how his face would have puckered up into protesting smiles!) Yes, people liked his work, and they liked him. He never roughed anybody: a man with such a genial, sympathetic nature was always welcome. He was companionable, he was retiring. If he had been asked whether he would like to spend his evenings performing the duties of President of the Royal Academy, or playing a game of snooker pool with his friends, I know what answer he would have made. He never talked about himself, so it happened that although we met constantly for years, I did not know, until after his death, that in his youth he had been a great athlete. He was the holder of the London Athletic Club's Challenge Cup for walking in 1876, and he was a good man with the oar, and a splendid cross-country runner. Yet when I come to think of it, that trim figure, and the bird-like movements of that active body showed that he had practised and retained the advantages of physical culture.

Left: Cromer. (The property of Mrs Pidgeon.) Source: Hind 153. Right: Near Southbourne (The property of Mrs S. N. Bolton). Source: Hind 154.

When the Hogarth Club closed, Wilfrid Ball was one of those who migrated to the Arts Club, and when in 1895 he married Miss Florence Brock-Hollinshead, and went to live at Lyming- ton in Hampshire, naturally we did not see so much of him as formerly. He would come to town for " Varnishing Days," or to attend a Council Meeting of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers, or a dinner of the " Sette of Odd Volumes," of which he was a popular member, or to hang a one-man show of his works at the Fine Art Society's or Dunthorne's; and on those dates, looking in at the Arts Club it was a distinct joy to me to see Wilfrid's smile, that rippling puckered smile, and to hear him ask for news. Oh, yes, we always had what Border Men call a "crack" about the old days, and latterly about the strange new days in which we are living. He deeply regretted that he was over age (he was born in 1853) and so could not offer his services to his country. The last time I saw him, in the Academy week of April 1916, we mingled our regrets at being "out of it," and he filled his much-used, much-scarred pipe, almost viciously, because he was "letting go" at the Boche, and sorrowing for the English boys, many our friends, who are no more. And I remember we talked about The Studio which was planned in the old Hogarth Club days, when Mr. Charles Holme was a member, and for which Ball wrote and illustrated charming articles, one on "Egypt" in 1893, and another later, on "Venice as a Sketching Ground." So we talked and parted, and with that parting [150/151] his bodily presence passed out of my life for ever.

Early Morning: Venetian Lagoons. Source: Hind, facing p. 154.

For in May I went to live in the country, and was rather out of touch with things; and when I thought of Wilfrid Ball I thought of him as the English Village Painter of these days, of the village green, the village pond, lanes, woods, and lakes, for he loved to paint water, and loved the serene simplicity of Bosham, the Hamble river, and Lymington. I thought of him easing the agony of many of the days through which we have lived since August 1914 in trying to pursue the happy avocations of peace-time.

Then one day — it was February 19 of this year — I received a letter from his wife which startled, shocked, and grieved me. And yet it was a beautiful death — a death one may envy. It may be summed up in the following brief announcement: " Wilfrid Ball, R.E., died at Khartoum on February 14th, 1917, from heat apoplexy, aged 64."

That was the bald, cruel fact, and the details, the steps that led up to it, are as follows. Since the war began, anxious to serve his country, he had taken up, and performed with a will, uncongenial war work. While he was doing this news came to him that the firm of accountants with whom he had been associated as a youth were short-handed at their Cairo branch. The need for extra help was imperative as most of their staff had joined the army. Wilfrid Ball saw his duty clear, and, without any fuss, left England for Cairo in September 1916, to become an accountant again at the age of 63. He had been there but a short time when a message was received from the Commandant at Khartoum saying it was absolutely necessary that some one should be sent at once to audit the military accounts. Ball volunteered, knowing well that, owing to the excessive heat, the risks a man of his age ran were grave. The rest we know. He did his duty. No one can do more. All his friends agree, entirely and proudly, with a sentence in his wife's letter to me: "It was as much a sacrifice as if he had died in the trenches."

Left: A Wet Day, Bosham. (The property of Dr. Neville Blagg.) Source: Hind 157. Right: Southampton Water, from Warsash. (The property of Arthur R. More, Esq.), Source: Hind 157.

The illustrations that accompany this article illustrate admirably the purpose and the performance of Wilfrid Ball's art. It never fell was placid and serene, and instinct with a deep below an accomplished level; it never attempted love for the rural scene and the unassuming wild experiments, or soared into rhetoric. It pastoral. It was placid and serene, and instinct with a deep love for the rural scene and the unassuming pastoral. Although Holland, Italy, France, and [157/160] Egypt were included in his sketching grounds, he was essentially the painter of the English Village. Nowhere, I think, is his talent more completely expressed than in the two books on Hampshire and Sussex he illustrated for Messrs. A. and C. Black. The quiet, faithful scenes follow one another, like still, sunny days in those dear Home Counties, and I can imagine an exile in Khartoum, the burning sun above, the burning sand around, growing heartsick with longing while looking at these two volumes expressing temperately the tempered sunshine of patted, petted, pretty, unchanging England.

Almost all his work was in water-colour. He painted a few oil pictures which were shown at the New Gallery and the Dudley; but he never felt quite at home in oil. His etchings were as successful as his water-colours. The series of the Upper Thames had a great vogue; his etchings were constantly hung at the Royal Academy, and he was awarded a Bronze Medal in Paris for his etching of Venice.

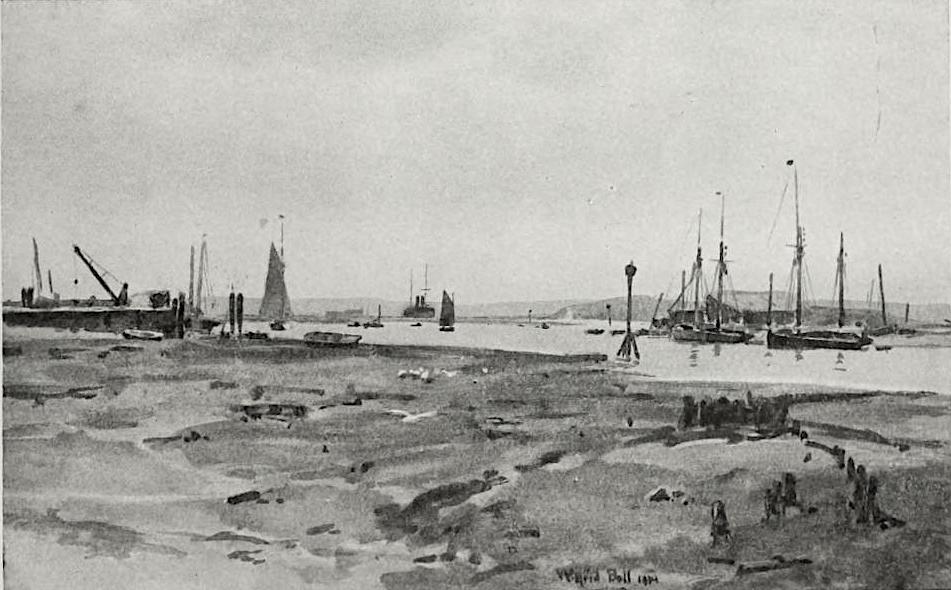

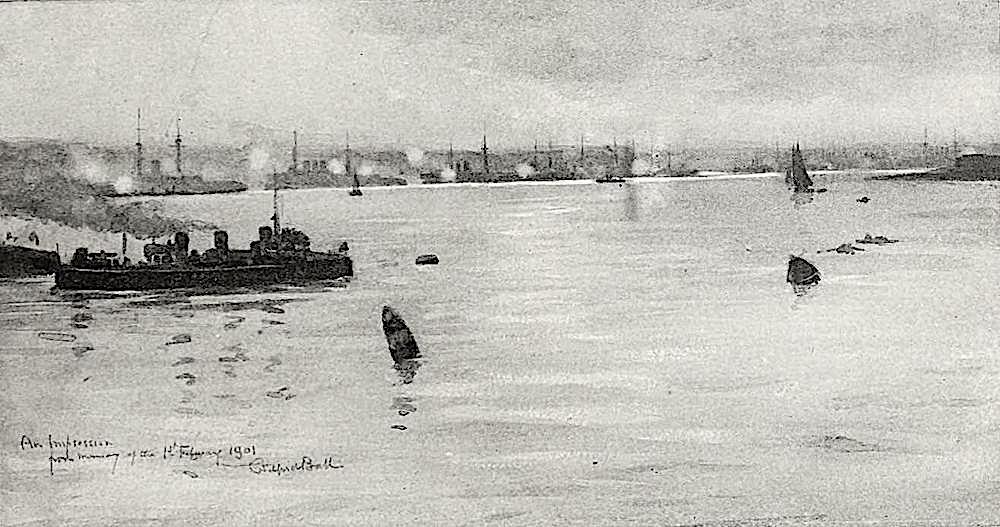

The Passing of Queen Victoria. (The property of Arthur R. More, Esq.), Source: following p. 157. Right: Torbay. (The property of George N. Stevens, Esq.). Source: following p. 157.

It was a quiet and happy life — and the end — how dramatic, how strange, how enviable! An English water-colour painter whose deepest love was for quiet English landscape — to die for his country at Khartoum, where Gordon died, where G. W. Steevens did his finest descriptive work, and whence Lord Kitchener, "who placed five million men between Calais and Khartoum," derived his territorial title!

Farewell, old Friend! You are remembered with love — you who loved our English hedgerows.

Bibliography

Hind, C. Lewis. "In Memoriam: Wilfrid Ball, Water-Colour Painter" The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art. Vol. 61 (Nos. 242-44, March-June 1917): 149-160. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts library, University of Toronto. Web. 11 September 2022.

Created 7 September 2022