All illustrations apart from the first come from our own website. Click on them to enlarge them, and for more information about them. — JB

Elizabeth Lowry has made her mark as a writer of historical fiction: her earlier novels, The Bellini Madonna (2008) and Dark Water (2018) both won plaudits for their analyses of unusual minds. The later work was set in the nineteenth century with a suitably Gothic atmosphere. Now, in The Chosen, Lowry has turned to an apparently plainer tale, though one which also involves a considerable element of haunting, about the Dorset-born novelist and poet Thomas Hardy, and his long-suffering wife Emma.

When the facts are well known, there is a special onus on the author not to distort them, but to bring them into play in a wholly convincing way. The main events of Hardy and Emma's story are familiar enough: the couple met on Hardy's professional visit, as a young architect, to the church of St Juliot in Cornwall. The visitor was at once smitten by the incumbent's sister-in-law, Emma Gifford. His feelings were reciprocated, but the class divisions in their respective families created problems for them. Emma and her sister Helen were the daughters of a solicitor, while Hardy's own father was a stone-mason, or, at best, a builder. Nevertheless, after a courtship of four years, they finally got married in 1874, not near either of their family homes, but in London, at St Peter's, Paddington. It was a quiet wedding, but one at which Emma's uncle, then Canon of Worcester, officiated. Hardy would always be deeply aware of having "married above himself" (128).

St Juliot's Church, Boscastle.

The marriage would be an unequal one in other ways too, and Lowry probes it plausibly and sympathetically. Emma, who had literary ambitions herself, encouraged her husband to make his career as a writer. It turned out well for him. We see her making useful suggestions that would help shape Tess of the D'Urbervilles, which, rather to Hardy's distaste, she wants to call "our novel" (189). But she herself has no such support, and no such success. This is seen as perhaps the most important of the factors that "wrought division" between them, as Hardy put it himself in his poem "After a Journey." Emma was sidelined, as so many women of famous husbands were in those times, and probably still are. "Do not help him — to the extent of extinguishing your own life — but go on with former pursuits," Emma advises other women in her position. This is in one of the private diaries that Lowry shows Hardy reading after her death (88). Nor were there any children to bring up. Hardy's biographers cannot tell us the reason for this, but Lowry's fictional Emma declares, again in her diaries, "All I wanted was a child. If I'd had a child I could have stood it. He's made sure that there was never to be a sign of one for us" (74). The clear implication here is that this was a physical problem — in one episode, at least, "his fervour fails" (231). But it goes deeper than that: Emma says later, accusingly, "Outside your stories you've no life in you, or feeling" (260).

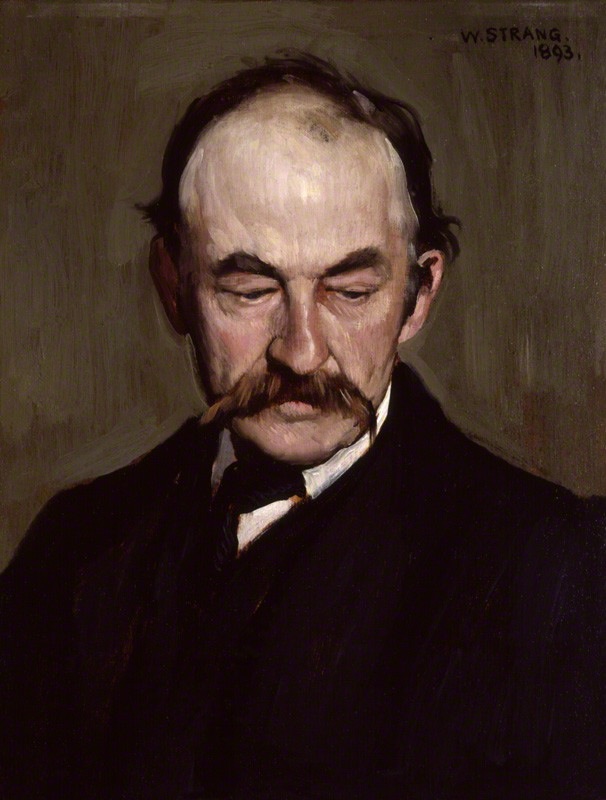

William Strang's portrait of Hardy in 1893.

Lowry imagines Emma telling Hardy this in an argument on the very day before she dies in 1912. By this time, the couple have long been estranged, living in different parts of the house that Hardy designed for them at Max Gate in Dorset. It was a situation that apparently troubled the now famous author much more after her death than before it. Again, as in her earlier novels, Lowry is drawn to look into a complex mind being forced to try and comprehend itself. Perceptive in the world of the imagination, Hardy would seem to have been unaware of the needs of the very person closest to him.

One of Lowry's aims is to to show how increased self-awareness, a belated understanding of a failed relationship, led to some of Hardy's greatest poetry, the volume entitled simply, Poems of 1912-13. In these lyrical verses, he expressed his grief not only over Emma's death, but, even more plangently, over the loss of that magical, romantic start to their courtship and marriage — and over his own part in its collapse.

The whole course of these events, therefore, is seen in flashback, with Lowry's opening chapter, "The Going," recreating the shock of Emma's passing, and the narrative moving forward as Hardy (with the help of her writings and felt presence) looks back. It must be said that the process is sometimes disorienting. But it does serve to keep Emma's past experience of the marriage, and Hardy's present exploration of it, in balance. By immersing us in the known biographical materials, and expanding them with added layers of frustration, disillusion and resentment, Lowry helps us as well as Hardy to inhabit Emma's unhappy world. At the same time, she shows Hardy coming to accept his part in the failure of the marriage: "My Emmie. What a poor excuse for a husband I was. You were loyal and true. But you're gone" (157).

One of the most telling exchanges comes in the penultimate chapter, when Hardy goes to visit his favourite sister Mary back in Higher Bockhampton, in the cottage in which he was born:

...What is it, Tommy dear?

"Did you all hate Emma?"

"I never hated her. She was a lovely thing when you first brought her to us. I thought she would bring you life."

"Did I lack life?" But he knows. "I did. Mary, I did."

"She hadn’t enough for 'ee, poor lass. She only had enough for herself, and you took that. She wasn’t strong enough to stop you. You took it and made a shadow of her. Then it was harder to like her."

"Oh, dear God." He bows his head. He can feel the cold air of the December day on his neck. “What shall I do?"

"You must learn to miss her, Tommy. That’s what you must do."

He holds tightly on to Mary’s hand. He won't lift his head, he won't look up. [254]

Note that Mary herself has admitted to Hardy, "We weren't always kind to her" (171). The blame for the failed marriage does not all fall on Hardy. Lowry's narrative is fair, convincing, often moving. When we reach the acknowledgments at the end, where a few rather minor departures from chronology are outlined and explained, we are inclined to believe that while The Chosen must be classed as fiction, it is, as Lowry hopes, "essentially true" (293). Even the fact that Emma's journal entries are part of Lowry's fiction seems acceptable, considering that Hardy burned the actual diaries after reading them. That in itself says much about their contents. Lowry adds that in writing these entries — this "catalogue of grievances" (103) — she drew on Emma's surviving letters "for their tone, and sometimes for their content" (294).

Max Gate in recent times.

The story does not quite end there. Not long after Emma's death, Hardy marries his long-time secretary Florence Dugdale. It seems like “a second chance at life. There's still time” (275). He has always been certain of Florence's goodness, he tells her; their relationship, and particularly his encouragement of Florence's literary leanings, had been another cause of bitterness to Emma. Yet this is still not the kind of fulfilment he had hoped for (of which he was quite probably incapable). When Florence decides to visit her parents at Enfield, he “can't bring himself to utter the word love" (275), but he escorts her to the station. Before they set out, she asks him “to try to sit at your desk for half an hour every day. Just half a hour,” and he replies obediently, “Yes, my dear” (277). She recognises and perhaps accepts more thoroughly than Emma that it is in writing that he finds his real fulfilment. She understands his ways well enough by now. After he simply squeezes her hand, there on the platform “she puts her mouth to his. Their lips meet” (278).

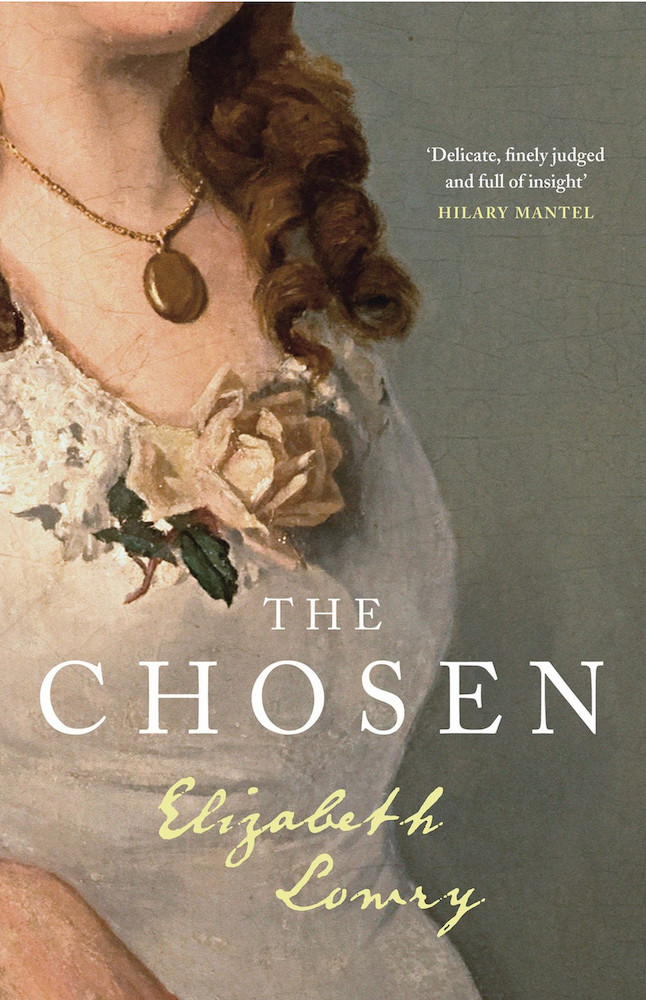

Portrait of Emma, aged thirty (the front cover

of Lowry's book uses a detail of this portrait).

Despite all the sadness of Hardy's first marriage, Lowry draws on the ideas and vocabulary of the poems themselves to provide a satisfyingly lyrical ending. After Florence leaves, Hardy instructs his driver to take him to Stinsford church where his family graves are. He chooses to go to the plot where Emma was buried, and, having made it neater, kneels there for a while, before walking back to the house at Max Gate where the two of them had lived their increasingly separate lives. And there, as in memorable poems like "The Voice" and "After a Journey," he is confronted by a vision of her that transports him back to the old days. Sitting at his desk again, he writes her one last letter: "It's been many years since I wrote you a letter, like this one, a love-letter. I am very much to blame. I thought there was no sense in writing, but I was wrong. I know you'll forgive me because you understand what I am, how simple, how unseeing.... I love you, Emmie. I've loved you from the day we first met: the never-to-be forgotten day." He signs off, "Ever your most loving husband, Tom" (290). What is pleasing here is that, despite the charges levelled against him, Hardy himself remains a sympathetic character.

By fleshing out the known facts, Lowry has done what so much recent literary criticism and neo-Victorian fiction does, that is, she has given the women in the life of a famous man their own voices, and their due, at last. But she has done so more temperately than some. As for those who object to the idea of such "fleshing out," they might bear in mind what Emma says in the novel to A. C. Benson, later to become Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge: "most biographies are fiction, I find" (221).

Bibliography

Lowry, Elizabeth. The Chosen. London: riverrun (Quercus), 2022. 296 pp. Hardback. ISBN 978-1-52941-068-6. £18.99

Created 18 July 2022