avid Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948) was issued just two years after his first Dickensian film, Great Expectations (1946). Both releases were met with universal acclaim and Twist, especially, was feted in the press as a ‘home-produced smash hit’ (Whiteley 5), a ‘masterpiece on celluloid’ (‘Oliver,’ Lewisham 7), and a ‘magnificent’ (‘Oliver,’ Eastbourne 13) adaptation of Dickens’s original. All aspects of the film were praised, with extravagant eulogies mentioning the ‘brilliant acting’ (Whiteley 5) and the intense black and white photography which, as noted by numerous critics, carefully recreates the style of George Cruikshank’s illustrations in the original edition of 1838 (Lewisham 7) and must have been used as visual reference. Above all else, praise was heaped on Lean’s directorial control and visual storytelling as he translated Dickens’s lengthy novel into a compact unit of sharply realized drama. All in all, Lean’s Oliver Twist was regarded as an exemplary piece; as Melvyn Bragg remarks, it was seen as ‘one of the great British films’ (182).

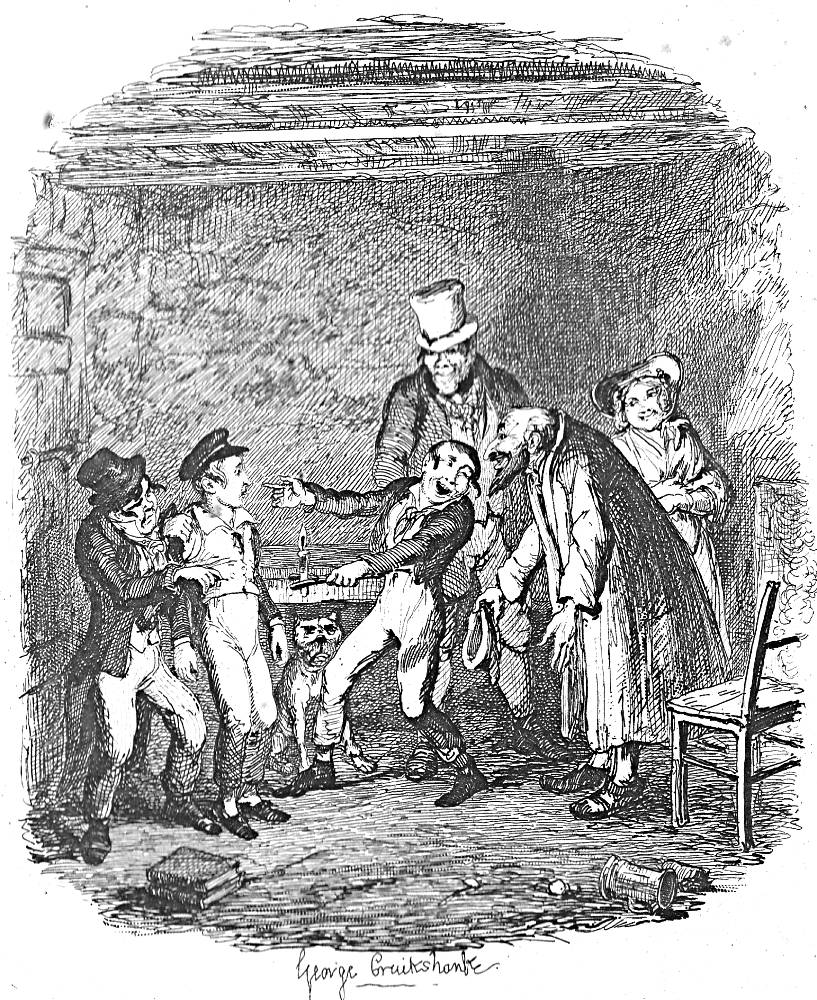

A publicity photograph in The Sketch showing the characters with enlarged heads.

Bragg was writing in 1980, and more than forty years after that assessment the film’s reputation is largely intact. It is interesting, however, to re-consider a work which is now almost eighty years old and now competes with several other visual treatments on the television and in the form of Roman Polanski’s successful version of 2005. In particular, it is possible to reconsider Lean’s creation through the lens of neo-Victorianism as a period piece, a reflection on the past which is itself part of the long-gone context of post-war Britain. Two questions are important to consider: how effective is the film as an adaptation of Dickens’s picaresque exploration of childhood and suffering? And how does it reflect not only on the Victorian novel, but on Britain in a period of trauma and recovery? These issues are important because they enable us, I believe, to analyse Lean’s complex cineplay in ways which uncover its strengths as a neo-Victorian translation of an established text while establishing its wider cultural significance.

Oliver Twist in the Twenty-First Century

Social and cultural values and attitudes invariably change over time, and all products of the past are evaluated, to some degree, from the perspective of the present. Describing a piece as ‘dated’ is meaningless as a critical term, but ‘modern’ attitudes inevitably inform our view of previous artworks, even if we recognize the dangers of anachronistic judgments. In the case of Lean’s Oliver Twist, the text is problematized by two elements which have complicated critical responses.

One of the difficulties in making sense of Lean’s film in the context of the present is the accent employed in some of the dialogue. Oliver, generally played very effectively by the child actor John Howard Davies, is supposed to be a northern waif but speaks non-regionalized Standard English in the idiom of ‘RP’ (Received Pronunciation). In this regard Lean merely follows Dickens – who makes his Oliver ‘well-spoken’ in order to avoid alienating the sympathies of his bourgeois readers, and there is certainly no trace of a ‘northern accent.’ But translated to the screen this linguistic strategy undermines Oliver’s poverty-stricken origins and implicitly identifies him as a Home Counties member of the respectable middle-classes. Indeed, this approach skews the film’s attempt to reproduce other class accents, notably Fagin’s (Alec Guiness’s) rasping tones, a version of English spoken by a non-native speaker, and the Cockney briskness and grammar of Bill Sikes (Robert Newton), Nancy (Kay Walsh) and Fagin’s juvenile gang. Oliver’s ‘clipped’ accent is the province of the stage-school, sounds incongruous within this verbal structure, and undermines the film’s attempt at rough-edged verisimilitude. The rest of the spoken dialogue film is brutal, brisk, frequently shouted in exclamations, and rich with slang and contractions; but Oliver speaks like one of the staid middle-class actors in Lean’s earlier films, notably Brief Encounter (1945). It is an approach that passed without comment in the 1940s in a period when there was a clear notion of linguistic correctness – speaking the ‘King’s English’ – but for observers in our own time seems ill-judged.

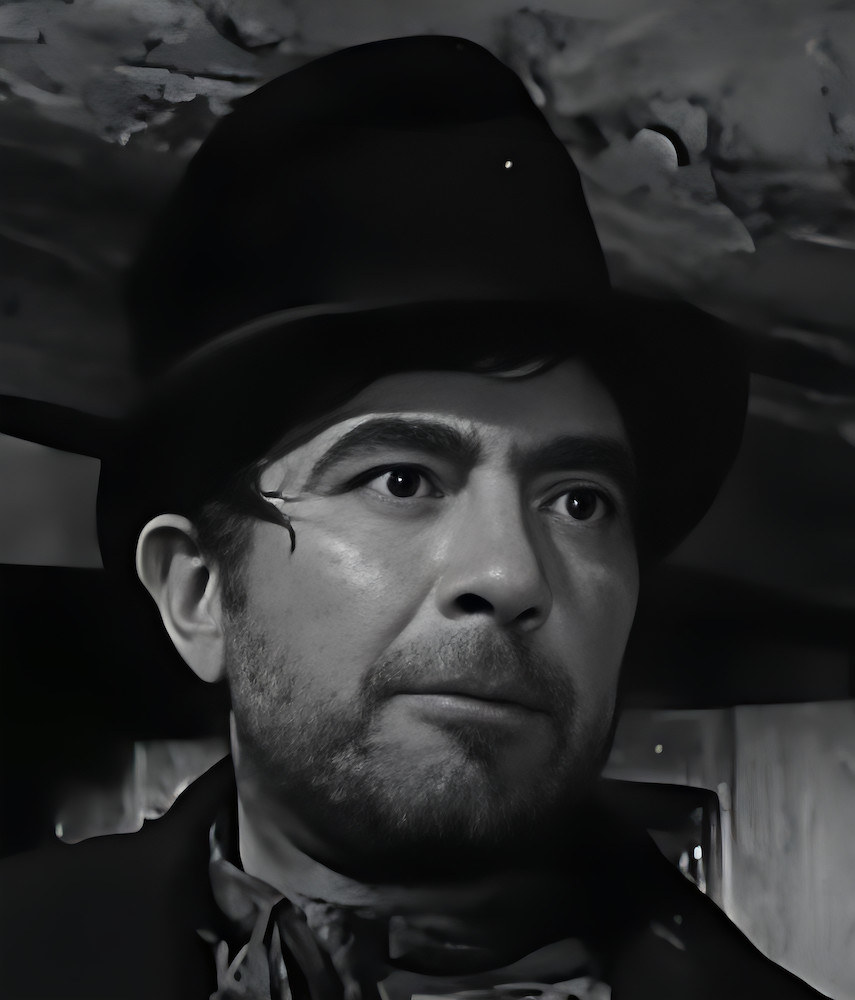

More difficult still, as critics such as Juliet John have observed, is the film’s representation of Fagin. Dickens’s character is of course an antisemitic type, presenting a stereotypical notion of Jews as avaricious and evil, and in Lean’s work the director both preserves and extends the cliché in the form of Alec Guiness’s exaggerated make-up. Dickens describes Fagin only in generalized terms as ‘very old’ and ‘shrivelled,’ with a ‘villainous-looking and repulsive face’ (Dickens, 1, 132), but Guiness is converted into a stage-caricature, with long greasy locks and beard and a ridiculously overlarge nose, the racist sign of Jewishness, that one critic has likened to a ‘toucan’s beak’ (McKee 43) and another to Cyrano de Bergerac’s absurd ‘proportions’ (‘Oliver Twist,’ Picturegoer 12).

Left: Guiness as Fagin, wearing a false nose; and Right: Cruikshank’s stereotypical characterization.

This treatment is pantomimic and, for many viewers, offensive. What is extraordinary is that the film presents this racist imagery, which echoes the visual tropes of Nazi propaganda, in the late 1940s. Lean was trying to reproduce the hook-nosed caricature in Cruikshank’s original illustrations rather than Nazi imagery, but he makes an artistic choice of bizarre (and strangely ignorant) insensitivity; in the blunt words of Maria Paganoni, his version of Oliver Twist is ‘complicated by the act of repositioning Jewishness within the cultural and political contexts subsequent to World War 2 and the genocide of the Jews’ (308). Guiness’s appearance certainly caused offence at the time of issue with foreign audiences if not with the British: fights broke out when the film was shown in Berlin in 1949 and its release was delayed in America until 1951, only being screened when cuts had been made to remove the more cartoon-like moments of racial stereotyping (Brownlow). From the date of its issue, Lean’s Oliver Twist developed a ‘prickly reputation’ (McKee 45) for its supposed antisemitism, and the presentation of Fagin continues to be an obstacle in modern assessments.

Issues of class and race thus complicate our reading of the film today. These, we might say, are its vices; but what are its virtues?

Adapting Dickens: From Illustration to Interpretation

Lean’s adaptation is an effective piece of neo-Victorianism which, despite its problematic elements, is still a concerted attempt to interpret the source material sympathetically in a form that was intelligible to viewers of the 1940s and still signifies today. Narrative, characterization and setting are figured to evoke the spirit of the original text while converting those elements into a modern cinematic language. In fact, Lean’s treatment can be clearly divided into aspects of his film in which he sets out to provide a literal translation of Dickens’s text and Cruikshank’s illustrations, and also shapes the material in order to provide a distinctive interpretation of the source-material.

The director’s starting point for his literal transposition was the narrative. Lean was far from a Dickensian scholar, but his reading of A Christmas Carol and Great Expectations had introduced him to the complexities of the author’s storytelling and the need, for any cinematic treatment, to produce a condensed version of the original. For Oliver Twist, he collaborated with the producer Ronald Neame to write a sharply-focused screenplay – drafted in just a month – that preserved the essentials of Oliver’s progress but omitted what the adapters saw as needless complications. The subplot involving Rose and Agnes Maylie is not included, and other events are removed or altered: Fagin’s time in the condemned cell is deleted; the shooting of Oliver at the bungled burglary, is removed, and Oliver is placed on the roof with Bill for the climactic finale. There are also changes in the characters’ roles, with some being conflated so that, for example, the betrayal of Nancy is taken from Noah Claypole and reassigned to the Artful Dodger.

These changes refigure the narrative in a manageable, linear form that was appropriate to the running time of under two hours. More especially, Lean and Neame’s alterations infused the text with the dynamic directness of cinema, completing the narrative adaptation by cutting the dialogue to terse exchanges and emphasizing the action, especially the more brutal events. As Mckee observes, the film ‘moves forward in staccato bursts propelled by coiling tensions and by outbreaks of sudden, brutish violence’ (41). In Lean’s hand, the author’s digressive writing style is replaced by a crisp visual montage, heightened by incisive editing, that efficiently directs the viewer from Oliver’s mother’s arrival in the workhouse to his final salvation in the household of Mr Brownlow.

This approach preserves the essentials of Dickens’s story and acts as a direct equivalent to the written narrative which, despite some changes, follows the same storytelling arc. Near-fidelity can also be traced in Lean’s characterization, which provides a cinematic match to the author’s emphasis on appearance as a sign of personality. Fagin’s character, as we have seen, in condensed in his villainous face, and it is noticeable that several of the main characters closely resemble Dickens’s descriptions and, more particularly, Cruikshank’s. The filmic Oliver is a good match with the graphic depiction, so is Brownlow (Henry Stephenson), and so is Bill, played with grimacing intensity by Robert Newton; the exception to the rule is Nancy, who is depicted by Cruikshank as a voluptuous figure but converted into a more conventional beauty by Kay Walsh.

Left: Cruikshank’s Oliver, as he attacks Noah; Right: John Howard Davies in the part.

Left: Cruikshank’s Bill, ‘Attempting to destroy his dog’; Right: a gurning Robert Newton, who excelled at such extravagant parts, and is here shown in the final minutes on the rooftop.

These visual types are broadly in line with the original text, and Lean preserves the intensity of Dickens’s characterization by privileging their faces in close-ups and in other dramatic images in which he stresses strong facial expressions. In Lean, as in Dickens and Cruikshank, the working of the characters’ minds is invested in their appearance rather than in their dialogue and utterances. The director thought of his film as ‘fantastic’ and ‘outsize,’ as a sort of fairy-tale or romance (Crabbe 47), and there is no doubt that his characters are visually intense, almost pantomimic in effect, and recreate the melodramatic extravagances of the Victorian original.

Left: Cruikshank’s visualization of Fagin’s seedy den; Right: the crepuscular set in Lean’s film.

Dickens and Cruikshank’s dual text was similarly observed in the settings and particularly in the treatment of interiors and the foetid backstreets of London. Dickens’s descriptions have the journalistic intensity of real observation when he speaks of ‘wretched’ places ‘impregnated with filthy odours’ (Dickens, 1, 129), and Lean’s art director, John Bryan, recreates this documentary realism in the shattered alleyways of a post-war capital and in the squalid interiors of rooms that are clearly based on Cruikshank’s domestic tableaux. Guy Green’s photography takes the effect further in his emphasis on chiaroscuro, presenting cinematic images that could almost be seen as animated versions of Cruikshank’s etchings.

Lean’s Manipulation of his Source Material

Lean’s recreation of these elements constantly link his film to Dickens and Cruikshank’s novel, providing a cinematic retelling that is never less than respectful of its source. Yet the film could not be described as a purely faithful rendition. As we have seen, narrative changes were made and characters rearranged, and it is more generally the case that Lean uses the parameters of his adaption as a framework within which to explore a more personal interpretation: not only an adapter, he was also an auteur who manipulated Oliver Twist to explore his own thematic concerns.

The director was primarily concerned with the concept of suffering and misunderstanding, with Oliver Twist, like many of his characters, being faced with inexplicable events and hostile environments. Oliver’s world is as warped and strange as the circumstances faced by Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Nicolson in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and in Oliver Twist, as in those films, Lean manipulates viewpoint so that events are presented from an omniscient point of view and from the perspective of the main character.

In this respect the director's approach differs from Dickens’s technique, which is purely a third person narrative, and focuses instead on subjective experience within the wider context of the storytelling. With Oliver as the centre, Lean starts this process by representing his mother’s travails as she struggles to find her way to the workhouse: Dickens offers barely any information, noting only that ‘she was found lying in the street’ and had ‘walked some distance’ (1, 6), but Lean shows her walking through a dramatic storm not in an urban setting but on a wind-swept moor. Lean’s approach, in other words, is a symbolic inscription of the character’s pain, using the pathetic fallacy to represent her anguish in the perpetual rain, in the drama of the skies, with black cloud and moonlight alternating in a febrile pattern, and in the jagged outline of a bramble which recalls the neo-romantic imagery of Graham Sutherland. No dialogue is spoken and the character’s inner turmoil is expressed in a visual way.

Two shots concerning Oliver’s mother, played by Josephine Stuart, as she struggles through the storm: Left: borne down by wind and rain: Right: the emblematic bramble that suggests her agony, outlined as an abstract form against a tumultuous sky.

Lean’s emphasis on the ‘primacy of the visual element’ (Petkovic and Vunic 40) has led some critics to describe Oliver Twist as a version of film noir (McKee 41), but in its use of light and dark it is probably closer to the style of German Expressionist cinema of the 20s (Petkovic and Vunic 42). Green, the cinematographer, explicitly set out to make the chiaroscuro menacing, using ‘diffused light’ to convey the ‘harsh’ (Brownlow) perceptions of Oliver’s mother in the opening scene, and throughout the film the darkness is deployed to suggest the fearfulness of her son’s progression into Fagin’s menacing, crepuscular world; noticeably, Oliver’s experiences with Brownlow are figured in bright light to form a moral and psychological contrast.

Close-ups of Bill and Fagin, each figured as ogres in the boy’s childhood perspective.

Oliver’s inner perceptions are further visualized in a variety of other forms. The huge close-ups of Fagin and Sykes suggest his child-like perspective, making the characters’ features monstrous and strange as he struggles to understand what is happening to him, and his disorientation is further suggested in the teeming excess of the urban scenes, with people in constant movement crammed into impossibly small spaces. Commentators have stressed the realism of the film, but in many respects it is an interior text, a map of Oliver’s mind rather than a representation of objective reality.

A confused Oliver is surrounded by a milling crowd; Lean compresses the space to make the scene claustrophobic and oppressive, as seen from the character’s point of view.

Lean stresses this subjectivity by deploying numerous POV (point of view) and travelling shots, in which we are literally placed behind Oliver’s eyes. When the Dodger takes him to Fagin’s den the camera recreates the character’s moving perspective as he climbs up the steps, and when he is pursued through the streets, following the bungled theft, we are carried in a series of thrilling dolly shots. Lean’s strategy is epitomized by the representation of the ‘clever blow’ (Dickens, I, 155) that fells Oliver. Dickens noted only that he is stopped, but Lean gives us Oliver’s first-person perspective as he is confronted by the man who hits him: the single punch is directed in a huge distorted close-up straight into Oliver’s – and the film-viewer’s face – followed by blackness as the boy is knocked out.

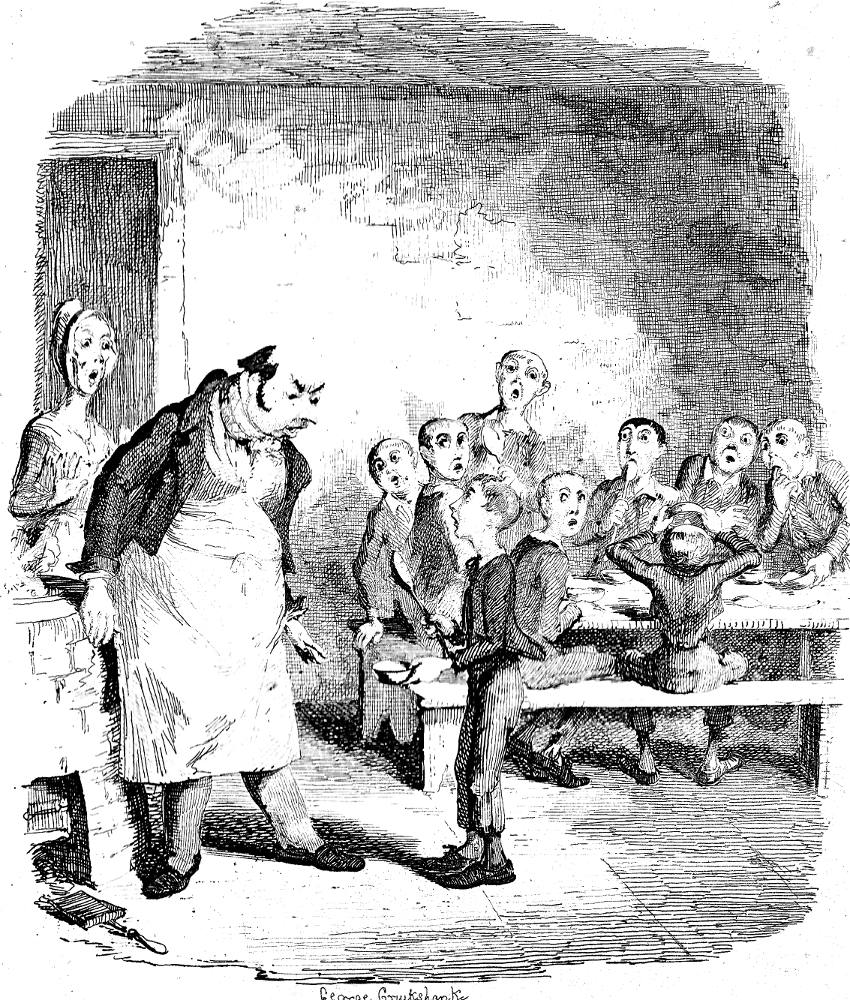

Two versions of a famous scene: ‘Sir I want, some more.’ Left: Cruikshank’s treatment; and Right: Lean’s expansion of space to suggest Oliver’s dread of having to make the request, visualizing a few paces into fear-freighted, extended steps.

This visceral subjectivism intensifies the film’s emotional effects, converting it from a respectful adaptation of an ancient text into the present tense of lived experience. In Lean’s film, indeed, Oliver’s traumas are deeply involving, and in each case the director finds a visual formulation to convey their impact. When Oliver goes to ask for more in the workhouse his reluctance is suggested by a shot of deep recession, with the supervisor’s cane twitching in the foreground; and his brutal treatment is generally suggested by the many scenes of manhandling, threats, violence and shouting, and by his fear as he looks at the coffins, looming out of the darkness, when he is forced to sleep in Sowerby’s workshop. In Lean’s film childhood is an existentially fearful space, a modern version of Dickens’s portrait of juvenile suffering, rendered in the terms of Expressionist cinema.

Lean’s Oliver Twist and Reflections on the 1940s

Oliver Twist analyses Victorian society as mediated through the lens of Dickens’s novel, and Lean’s cineplay also acts, it can be argued, as a commentary on the society of post-war Britain. Like all neo-Victorian works, it is necessarily about a time and the time in which it was produced. Indeed, its impact on the original viewers is largely generated by its only lightly coded reflection on several key issues which were sources of anxiety as Britain emerged from the prolonged struggle and tragedy of the Second World War.

Foremost among these points of cultural reference is Lean’s focus on the sufferings of Oliver, which could be said to refer not only to Dickens’s theme but also, as Melanie Williams observes, to the growing concern for the welfare of children in the post-war period (Williams). Britain’s children had, after all, been subjected to some terrible privations. Some had been orphaned during the war, and many were evacuees, and Lean dramatizes both experiences in an exaggerated and symbolic form as Oliver loses his mother and is placed under the grim guardianship of Bumble and the workhouse, moves on to Sowerby and the bullying Noah Claypole, and is finally taken into the gross, exploitative stewardship of Fagin. Many British children experienced loss, relocation and unsettling encounters with unsuitable guardians, and some of that experience is inscribed and amplified in the film. Though figured as a tale of how the Victorians treated their poverty-stricken children in the late 1830s, the film questions how a modern British society had and should treat its youngsters of the 1940s. Victorian cruelty is brought into focus, but contemporary cruelty resonates in the moving images as well.

So does criminality. Dickens’s novel explores the workings of crime in a period of great social instability, and Lean’s film reflects on the years of the War which, despite the official, propaganda version of Britain’s unity in a common purpose, were characterized by a crime wave. The murder rate increased, especially of young women, as in the case of the serial killer Gordon Cummins – an event referenced, perhaps, in Sykes’s killing of Nancy – and petty crime was widespread as gangs looted bombed-out houses and even stole from families while they were sheltering from air raids. Particularly commonplace was pickpocketing of the sort practised by Fagin’s gang: once again, the telling of a story set in the 1830s has application to the 1940s. This connection is not spelled out, but it was picked up by contemporary reviewers, as for example in one critic who noted how Fagin was a ‘fence’ (‘Oliver,’ Eastbourne 13) – a term popular in the 40s to describe a receiver and seller of stolen goods. Indeed, Fagin, Sykes and the gang are participants in a Victorian black market which may have reminded modern audiences of the ubiquity of this sort of illicit trading in the long years of the conflict with Germany and in the post-war period as the Labour government (1945–49) sought to stabilize the shattered economy.

The film’s violence and settings more generally reinscribe the character and conditions of the War. As noted earlier, Oliver’s treatment is brutal, but it is interesting that Lean ultimately chooses not to confront the horrors of killing. Dickens presents Bill’s murder of Nancy in melodramatic, but unsettling, terms:

The housebreaker … grasped his pistol [and] beat it twice with all the force he could summon, upon the upturned face that almost touched his own … She staggered and fell, nearly blinded with the blood that rained down from a deep gash in her forehead …It was a ghastly figure to look upon. The murderer staggering backward to the wall, and shutting out the sight with his hand, seized a heavy club and struck her down. [Dickens, 3, 195–96]

In the film, though, we only see some of the assault. The event is mainly represented by Bullseye’s whimpering and scrabbling against the door as he tries to escape – a horror too dreadful for even a dog to have to see. This brilliant device – achieved by placing a stuffed cat’s tail just out of sight – seems to embody the lingering sentiment at the end of sustained conflict and loss: the British people had had enough of killing and suffering; the implication of violence was enough.

Lean’s representation of the ruined state of the urban environment further reflects on the condition of London and many British cities as they recovered from heavy bombing. Fagin and all the other characters navigate gloomy backstreets, rotten with dereliction and decay, and the same can be said of Britain’s modern towns. More than this, the squalor is a demand for change and renewal. Lean had some socialist sympathies, and in Oliver Twist he reminds the audience of the need to move forward, under Labour’s programme of the 40s, to rebuild and modernize, to replace the wreckage of the cities, to sweep away the slums and to eliminate the urban poverty of the 1930s.

In short, Oliver Twist is a thoughtful adaptation of its source, an inventive piece of cinema in which powerful acting and imagery convey its messages, and a product of its time that uses an historical lens to meditate on its immediate cultural context. Its problematic elements remain, but it still acts as a powerful representation of a highly significant text of enduring interest and application. Dickens intended his novel to be didactic, and Lean figures his film in parallel terms as an appeal for compassion and new beginnings.

Filmography

Lean, David. Brief Encounter. Eagle-Lion, 1945.

Lean, David. The Bridge on the River Kwai. Columbia Pictures, 1957.

Lean, David. Great Expectations. Cineguild, 1946.

Lean, David. Lawrence of Arabia. Columbia, 1962.

Lean, David. Oliver Twist. Cineguild, 1948.

Polanski, Roman. Oliver Twist. Pathé, 2005.

Bibliography

Bragg, Melvyn. ‘Literature and the Screen in the United Kingdom Today.’ India International Centre Quarterly 7, no. 3 (September 1980): 175–185.

Brownlow, Kevin. David Lean: a Biography. London: Faber, 1997; Google books online edition.

Crabbe, Katharyn. ‘Lean’s “Oliver Twist”: Novel to Film.’Film Criticism 2, no, 1 (Fall 1977): 46–51.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. 3 Vols. London: Richard Bentley, 1838.

John, Juliet. ‘Fagin, the Holocaust and Mass Culture: or “Oliver Twist” on Screen.’ Dickens Quarterly 24, n. 4 (December 2005): 2004–223.

McKee, Al. ‘Art or Outrage? “Oliver Twist” and the Flap Over Fagin.’ Film Comment 36, no 1 (January –February 2000): 40–45.

‘Oliver Twist.’ Eastbourne Gazette (8 September 1948): 13.

‘Oliver Twist.’ Lewisham Borough News (4 July 1948): 7.

‘Oliver Twist.’ Picturegoer (23 October 1948): 12.

‘Oliver Twist.’ The Sketch (21 July 1948); 18.

Paganoni, Marie Cristina. ‘From Book to Film: the Semiotics of Jewishness in “Oliver Twist.” Dickens Quarterly 27, no. 4 (December 2010): 307–320.

Petkovív, Rajko, and Vunic, Kresimir. ‘Symphony of the City: “Oliver Twist” and David Lean’s Film Adaptation.’ Journal of the Association – Institute for English Language and American Studies 10, no. 11 (November 2021): 30–48.

Whiteley, Reg. ‘Schoolboy John Becomes World Film Star.’ Daily Mirror (23 June 1948): 5.

Williams, Melanie. David Lean. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014. Online edition, Google books.

Created 4 September 2025