The author has kindly shared these materials with readers of the Victorian Web, who might wish to consult his extensive website.

In 1988, on the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, William Knibb was granted Jamaica's highest civil honour, The Order of Merit. Only one other non-Jamaican and no white man shared this honour at the time. In a powerful article advocating this award Devon Dick stated

He was for the black man and had great faith in the untapped resources of the negroes. No other person of his era demonstrated such faith in the prowess of the black people.

- For Knibb's work as Liberator of the slaves;

For his work in laying the foundation of Nationhood;

For his support of black people and things indigenous;

For his display of great courage against tremendous odds;

For being an inspiration then and now.

His lifetime's work in a nutshell! William Knibb's legacy is to be seen in the Coat of Arms of his native Kettering — a black figure stands on the right with, dangling from his left wrist, a broken chain, symbolizing William's pioneer work in the cause of the abolition of slavery. Would that in this century William Knibb were recognised elsewhere than in Jamaica and Kettering as the great man he was. Whereas Clarkson, Wilberforce and others were resigned to the eventual abolition of slavery, William Knibb secured its immediate abolition in the British Empire, paving the way for it to be later abolished elsewhere — much later in many colonial countries.

The Reverend William Knibb was born a twin on 7th September 1803 in the family home in Kettering, Northamptonshire, the third son of Thomas, a tailor, and "poor but noble" wife Mary, née Dexter. There were eight children in total, and life could not have been comfortable, since his father, often the worse for drink, was declared insolvent in 1810. William's mother Mary, the pious religious partner of the marriage, was a teacher and member of the nonconformist Kettering Independent Church called "The Great Meeting," the building now part of The Toller Chapel. William's formal schooling only lasted to the age of 12 and more than one commentator has remarked on his skill at playing marbles, rather than upon any academic brilliance.

He also attended from the age of 7, the Reverend Toller's Sunday School with brothers Thomas and Christopher (later a draper in Birmingham). William's Sunday School teacher had, according to some reports "early on recognised the lad's maturity for his age and the compassionate side of his nature" and others quote Mr Gill "a good boy but somewhat volatile and very difficult to manage until his affection had been gained." He looked like and looked up to Thomas, four years his senior. The two boys followed similar career paths. Both became apprenticed in turn to Mr J. G. Fuller whose printing business was in Gold Street, Kettering, close by his father's Baptist church. Indeed, the Reverend Andrew Fuller was a founding member, with William Carey, John Ryland, Reynold Hogg and others, of the Society formed in Kettering "for propagating the gospel among heathens", destined to become the Baptist Missionary Society.

In 1816, the printing business removed to Bristol, Thomas and William moving with it. Mr Fuller became the Superintendent of the Broadmead Baptist Church and the brothers were drawn to its Sunday School. They were further exposed to the work of the Baptist Missionary Society through printing of its pamphlets and accounts. Dr John Ryland, Pastor of the Broadmead Church and Principal of Bristol College, the oldest Baptist theological school, was also on the Executive Committee of the Baptist Missionary Society.

Thomas Knibb led the way to Jamaica, with his bride "Bett," having been accepted as a teacher in 1822, the year William committed himself fully to God. They were both baptised by Dr John Ryland himself. Within 14 months of beginning to teach at the school in Kingston, and before he could make any real impact, tropical fever struck Thomas down in April 1824 (sic). William, who was regarded as less able than Thomas, immediately wanted to take his brother's place. This despite the death also in Jamaica of his friend Samuel Nichols, assistant to James Coulthart, who was himself ill at the time.

He succeeded in persuading the Baptist Missionary Society to allow him to go to Jamaica. He first married fellow Church member Mary Watkins in Bristol; her background in South Wales is obscure, apart from the fact that her parents died when she was young. She spoke fluent Welsh. Before setting off, he took her to meet his family in Kettering, where his mother wished them God's speed. Later her nephew Benjamin Dexter, the son of her brother Worcester Dexter, was to make the same journey as a Baptist missionary with his wife Ann.

An early signed portrait (courtesy of Rose Marie Harrison née Knibb)

From teaching at mission schools and preaching at various places without at first licence to do so, William eventually achieved full pastor status at Falmouth. To him from the outset, the whole concept of slavery was totally abhorrent, and he determined to do all within his power to "slay the monster" that was slavery. However, the Baptist Missionary Society relied upon the goodwill of the masters on their sugar plantations and could not support (at least openly) the emancipationist movement. Missionaries were firmly instructed and reminded not to interfere in civil or political affairs. This was their stance right up to the reception of William's speech at their public Annual Meeting in Spa Fields Chapel on 21st June 1832.

"I call upon children, by the cries of the infant slave who I saw flogged on the Macclesfield Estate, in Westmoreland. . . . I call upon parents, by the blood streaming back of Catherine Williams , who, with a heroism England has seldom known, preferred a dungeon to the surrender of her honour. I call upon Christians by the lacerated back of William Black of King's Valley, whose back, a month after flogging, was not healed. I call upon you all, by the sympathies of Jesus".

At this point, Mr Dyer, Secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society, is stated in the Patriot to have pulled the tail of his coat by way of admonition.

"Whatever may be the consequence, I will speak. At the risk of my connexion with the Society with the society, and of all I hold dear, I will avow this . . . . Lord, open the eyes of Christians in England, to see the evil of slavery and to banish it from the earth."

William's oratory brought thunderous applause and by the end of the evening Dyer himself had proposed the next round in the struggle — a public meeting at Exeter Hall.

William made several enemies amongst the planters, traders and merchants whose livelihood rested upon slavery and the slave trade, still in full swing on many ships operating outside the jurisdiction of the British Empire. William Wilberforce and others had been famously instrumental in getting the British involvement in the slave trade banned in 1807.

Whilst he was more than once accused of inciting slaves to revolt, he never did so, relying upon his acquired skills as a prolific letter writer and orator to turn the minds of men who mattered. Early on, he was threatened with withdrawal of his Licence to preach, having given persistent and public support to Sam Swiney, a deacon of his who had been flogged for preaching when, in reality, only praying with others during William's absence. Later, at the time of what became known as the 'Christmas Rebellion' in Jamaica, he was arrested and threatened with death by the Authorities. The revolt, allegedly led by Sam Sharp, occurred when the slaves mistakenly thought that freedom had already been sanctioned by the British Parliament. William had to convince his congregation that this was not the case and he advocated strongly against violence as a means to achieve freedom from slavery. There was little trouble where his influence extended but that did not stop the militia burning down his chapels and schoolrooms. After seven agonising weeks, the charges against him were eventually dropped for lack of evidence. During his career, he was more than once cruelly libelled, notoriously by the John Bull newspaper - see Knibb v Bunney. The British press were generally hostile as they represented the planters' point of view. Ill-informed articles in The Times during the century were incredibly biased towards them and were sure to engender racialist hatred. Such reporting nowadays would thankfully send an Editor straight to jail.

After the Christmas riots, William was chosen to go to England to represent there all the other Jamaican Baptist Missionaries. The purpose of the trip was to explain what had happened and to raise money for the rebuilding of the burnt out missions, his own included, fired by the militia during the insurrection. His arrival in 1832 coincided with the passing of the Reform Bill, which would see a more representative House of Commons. On hearing the news, he exclaimed 'Thank God, now I will have slavery down'. First he had to account for his actions in Jamaica before seeking the money to rebuild the Churches but took every opportunity to bring to the public's attention the evil of slavery.

|

Facts and Documents connected with the Late Insurrecion in Jamaica and the Violations of Civil and Religious Liberty arising out of it Extracts: "The Baptist Chapel at Falmouth had been occupied during Martial Law as Barracks by the St Anne's Regiment. . . . It was completely demolished. . . . information was given to Lieutenant Thomas Tennison. . . . "it was no matter whether they broke it or not, he supposed they would set fire to it too!" Mr Knibb ... paid a visit to Falmouth early in March. For three successive nights his lodging was stoned, and he was cautioned by two respectable gentlemen, against venturing out in the evening, as a party had clubbed together to tar and feather him. After Martial Law was discontinued, the horses of Mr Knibb were taken from Falmouth, by Major General Hilton, who has, until very recently retained posssession of them." The full publication contained a Memorial by the Baptist Ministers seeking relief from the Governor of Jamaica and other relevant documents designed to make the British Public aware of what had happened at the time of the Insurrection. |

The Missions were always short of capital and resources, not least because William always endeavoured for his chapels and schools to be self-sufficient but of course that didn't take account of the 'great and glorious' destruction of the 'pestitlential hole, Knibb's Preaching Shop' by the Militia — those words used in letters printed in The Jamaica Courant which published other letters in similar vein. The losses and expenses amounted to £23,250 in Jamaican currency but the Governor refused to meet the claim.

The Notice below was surely inspired by William's stand at the 21st June Annual Meeting of the Baptist Missionary Society, and he certainly made use of it by including a copy of the Notice in the Facts and Documents publication.

RESOLVED That the principles of Christianity and slavery are so entirely opposed to each other, that the only remedy for these evils is the immediate and complete extinction of slavery; and that is the opinion of those meeting and that in the approaching General Election, it is the duty of every friend of humanity and Christian religion, to give a decided preference in his vote to those candidates who will support in Parliament, such measues as shall have for their end the accomplishment of this desirable object.

From a Special meeting of the DEPUTIES from the several Congregations of PROTESTANT DISSENTERS of the three Denominations in, and within twelve miles of London .... 26th July 1832 as extracted from a Notice in 'The Times' the following day and included in the 'Facts and Documents' already quoted.

William Knibb's determination had won over the Baptist Missionary Society Committee to recognise that slavery had to be abolished. He argued that until its abolition 'root and branch' there was no way of slaves enjoying everything the gospel had to offer. Notably he spoke at a packed public meeting of the Friends of Christian Missions, Exeter Hall, London on 15th August 1832, where it was said that his face 'glowed as he spoke with impassioned sincerity and fervour for the cause'.

I look upon the question of slavery only as one of religion and morality. All I ask is, that my African brother may stand in the same family of man; that my African sister shall, while she clasps her tender infant to her breast, be allowed to call it her own; that they both shall be allowed to bow their knees in prayer to that God who has made of one blood all nations as one flesh

From William Knibb's speech at Exeter Hall, The Strand, London on 15 August 1832, at which he raised to the full view of the 3,000 present, iron slave shackles, which he hurled deafeningly to the floor. Those same shackles were over 70 years later donated to the Baptist Missionary Society and were lent to the Kettering Manor House Museum in 2003 for their exhibition as part of the bicentenary celebrations of William's birth.

The speech was received with 'deafening applause' albeit that 'The Times' reporter present quoted the by then famous speaker as 'Mr Nibbs'. To redress that, Printed Reports of the Speeches ran to at least three editions — the third, 5,000 copies.

William embarked upon a series of public meetings throughout the length and breadth of the Kingdom to make known his repugnance of slavery. He was accompanied at times by Thomas Burchell who had joined him from America.

Devon Dick in 'William Knibb: A National Hero?' recounts his exploits as follows:

To mobilise the entire British populace against slavery was a daunting task because the anti-slavery feeling was not widely diffused or intense in Britain. It was the pastime of idealists. To achieve his aim, Knibb travelled in five months six thousand miles, in the process attending 154 public services and addressing 200,000 people throughout Scotland, Ireland and England. No other person did a tenth of the volume of work that Knibb did. Knibb used mordant satire and gave lurid accounts of the atrocities to convince the people. He was the most sought after and effective of of anti-slavery speakers. He defeated the subtle Mr Borthwick, a pro-slavery advocate, in many a debate.

His speeches to packed audiences were regularly printed in pamphlet form and were reported in local/national newspapers, thereby reaching many more thousands of electors. Having come to prominence, William gave forceful evidence, with others, for several days before Committees of both Houses of Parliament.

After a long struggle and the passing of the Abolition of Slavery Bill, slavery was to be abolished in British Colonies as from 1 August 1834, with £20 million compensation to be paid to the slave owners, but for six years those over six years old were to be apprenticed to their former masters, so full freedom was still not achieved. The apprentice system was much abused, particularly the price that apprentices had to pay to acquire their freedom. The gross amounts sought hardly supported the planters continually voiced complaints that the negroes were lazy. Nothing infuriated William more than this widespread accusation which he was able to demonstrate time and time again was an unjustified slur on the blacks. As he wrote in a letter to Mr Eustace Carey in February 1835

You may have heard that the apprentices are lazy and idle, and this is just as true, as that they have "four parlours and a saloon." Though attempts have been made to annoy them, and though a most iniquitous law has been passed, which compels night-work, still they submit.

Continued pressure by William and others eventually reduced the period of apprenticeship to 4 years. So it was that on 1st August 1838, the 'monster' of slavery was finally dead. "The hour is at hand, the monster is dying" as recited by William Knibb on 31 July 1838 at his Falmouth church, Jamaica moments before midnight, the time set for the final abolition of slavery. Once the church bell had struck, he shouted "The monster is dead; the Negro is free!". A pair of shackles were then buried in a coffin with a sign over the grave. "Colonial Slavery died 31 July 1838, Age 276 years".

The peaceable way in which emancipation was achieved and celebrated gave William much satisfaction. There was no rioting nor drunkeness and no blacks committed crimes as the Authorities had feared. A fitting celebratory plaque, was affixed above William's pulpit in the Falmouth Chapel.

I here pledge myself, by all that is solemn and sacred never to rest satisfied, until I see my black brethren in the enjoyment of the same civil and religious liberties which I myself enjoy, and see them take a proper stand in society as men" declared William Knibb on 1 Aug 1838 at a public meeting in Falmouth, Jamaica, the first day of freedom for the slaves.

Even so, the former slaves were more or less left at the mercy of the plantation owners regarding eg fair and proper payment of wages. New taxes were introduced which were grossly unfair. Once again it was William who took up the cudgels on behalf of the oppressed, making further trips to England in this respect and to counter spurious allegations made against him and his fellow missionaries. He published accounts showing all income and expenditure of his Mission, and though it pained him to talk about his own lifestyle (which was unquestionably humble) he produced a receipt for 15 pounds for the 'so costly magnificent car in which the pope of Jamaica (for so accusers called him) visits his diocese'.

He apologised not for straying into the political arena because of the many new measures which impacted on the freed slaves. He spoke out against capital punishment, European immigration to Jamaica (which was killing thousands unaccustomed to the climate). He denounced the need for and cost of an armed police force, giving detailed evidence of the lack of crime committed by the emancipated population. His publicly reported speeches of the time to packed audiences wherever he went demonstrated once again his popularity and the huge influence upon those who attended. But he never gloried in his success, all commentators agreeing upon the fact that his fervent commitment to the cause and his utter humility shone through. He publicly refused to accept the title "The champion of the negro," giving credit to others, such as Burchell, whom he thought hid their light under a bushel.

This is what William looked like around this time. It's a copy of a Baxter print commissioned by the Baptist Missionary Society which was given away in a series of three baptist luminary pictures with the Patriot magazine. This one comes from a copy kindly supplied by the New Baxter Society. Note the silver inkstand shown on 'The Antiques Roadshow'.

In September 1839, he founded the weekly newspaper the Baptist Herald and Friend of Africa which gave the emancipated slaves a voice of their own and inspiration to better themselves.

A major accomplishment for him, on his last trip to England, was to persuade the Baptist Missionary Society to start missionary work in Africa. His daughter Catherine later went with her husband Captain Thomas Milbourne on a Missionary ship to the West African coast. This took a toll on her health and, returning to Jamaica, she died there in 1858. Their daughter "Minnie" left Jamaica for England where she was taken to meet her prospective stepmother by Mary, who was herself in England 1861-1862.

A unique and highly successful innovation of James Phillipo, readily adopted by William, was the system of Free Villages. He acquired land (usually via agents as the owners would not have sold to him) for settlements where emancipated slaves could live and build houses free from the threat of eviction from their former Estate hovels. He personally stood surety for all monies borrowed but conveyed the land to the mission. He founded new chapels at each and both Sunday (for religious study) and day schools to educate the young, organising the training and appointment of teachers. One such township, Kettering (appropriately named for its associations), was founded nine miles outside of Falmouth, where his principal church remained. Two others were the free villages of Hoby Town & Birmingham in Trelawny in memory respectively of his friend Dr James Hoby and Joseph Sturge of that City in England.

He helped found the Calabar seminary at Rio Bueno for the training of local men for service to the Baptist Missionary Society in the West Indies and Africa. "Massa Knibb," as he was addressed, in all baptised around three thousand of his poor "blacks," the term he used himself, each spiritually readied for the event — he would not baptise anybody merely to swell the numbers. In tribute to his works, many emancipated slaves adopted the surname Knibb.

Personal tragedies were the deaths of most of his children at very young ages and worst of all his adored eldest and namesake aged 12 years in 1837. The youngster had already begun to follow in his father's footsteps in caring for the children of slaves and was beloved by them. Hoby wrote a book about him and a memorial plaque is located in the Falmouth Baptist Chapel — not to be confused with William's memorial outside the church:

The same God who made the white made the black man. The same blood that runs in the white man's veins, flows in yours. It is not the complexion of the skin, but the complexion of character that makes the great difference between one man and another." So spoken on 1st August 1839 at a meeting of the Falmouth Auxiliary Anti-Slavery Society chaired by a black man.

Freed slaves, writes his great granddaughter, Inez Knibb Sibley (descended via daughter Ann & the Rev Ellis Fray, a black graduate of the Calabar seminary), gave William his house at 'Kettering' where he died of fever at the age of 42, before he could accept an invitation to go to America to speak against slavery there. He left Mary his widow and their three surviving daughters, two of whom married; Ann and Catherine (as both mentioned). An estimated 7,000-8,000 people thronged around the Falmouth Church for his funeral just 25 hours after his death, so quickly did word spread.

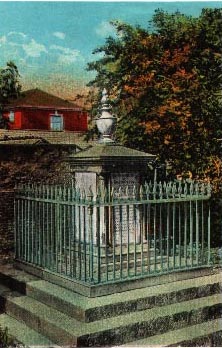

Here's an old photograph of his tomb erected outside the Church at Falmouth with the inscription written on it alongside.

|

To the Memory of William Knibb Who departed this life on the 15th November, 1845, in the 43rd year of his age. This monument was erected by the emancipated slaves to whose enfranchisement and elevation his indefatigable exertions so largely contributed; by his fellow-labourers, who admired and loved him, and deeply deplore his early removal; and by friends of various creeds and parties, as an expression of their esteem for one whose praise as a man, a philanthropist, and a Christian minister, is in all the churches, and who, being dead, yet speaketh. |

|

Photo by E Wells Elliott |

Even in this day and age, the World needs men as forceful and courageous as William Knibb to eradicate slavery once and for all.

Related Web Materials

- http://website.lineone.net/~gsward/pages/wknibb.html

- http://www.broadmeadbaptist.org.uk/knibb-rh.php

- http://cockpitcountry.com/falmouth/knibbchurch.html

- Here's a tale from 'The Missionary Herald' about 'The Stolen Girls' which shows yet another aspect of William's humanity.

Bibliography

Baptist Missionary Society. The Man Who Could Not Be Silent. London: The Carey Press, nd.

Catherall, Rev Dr. G. A. "William Knibb, Freedom Fighter." (Author's Manuscript Copy)

Dick, Rev. Devon, JP MA BA. "William Knibb: A National Hero?" Published in 1987 (Photcopy manuscript kindly supplied by the author who is Pastor at The Boulevard Baptist Church in Kingston, Jamaica and Chairman of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust.)

Facts and Documents connected with the Late Insurrection in Jamaica and the Violations of Civil and Religious Liberty arising out of it. London, 1832.

Hall, Catherine. Civilising Subjects. .Polity Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7456-1821-9.

Hinton,John Howard. Memoir of William Knibb. Second edition. London: Houlston and Stoneman, 1849. (two copies, one Mary Knibb Milbourne's copy)

The Kettering Connection — Northamptonshire Baptists and Overseas Missions. Edited by R.L. Greenall containing an item on William Knibb by Rev Dr G A Catherall. Department of Adult Education, University of Leicester 1993 ISBN 0 901 507 45 8.

Kettering Return of Enrolment 1 Aug 1803, Religious Persecution in Jamaica - Report of the Speeches of The Rev Peter Duncan and The Rev W Knibb (Exeter Hall, 15th August 1832), various newspaper cuttings and tributes.

Knight, R. A. L. William Knibb Missionary and Emancipator. London: The Carey Press, 1924.

Payne, Ernest A. Freedom in Jamaica. London: The Carey Press, 1933.

Smith, Mrs John James. William Knibb: Missionary in Jamaica. A Memoir. �London: Alexander & Shepheard, 1896. (ie Mary Esther Smith - Carrie Hutchen née Smith's copy)

Wright, Philip. Knibb The "Notorious" Slaves' Missionary, 1803-1845. London: Sidgwick & Jackson� London, 1973.� ISBN 0 283 97873 3

Last modified 2003