he second half of 1900 was a momentous period for Australia's six self-governing colonies: New South Wales, Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Queensland. As the indvidual colonies had grown during the settlement years, they had developed their own feelings of identity and their own systems of government, with different regulations for everything from trade to travel. But after a long process dating from as far back as the 1840s, the idea of a federation had gained ground in the 1880s. A united defence had proved to be an important incentive (see Clark 163). In July 1900 therefore, Queen Victoria was called on to give Royal Assent to an Act that would make the whole land a Commonwealth. Later in July, only about three weeks after the Assent was given, the results of a referendum brought the last outstanding colony, Western Australia, into the fold. That September, the former Governor of Victoria, Lord Hopetoun, became the country's first Governor-General.

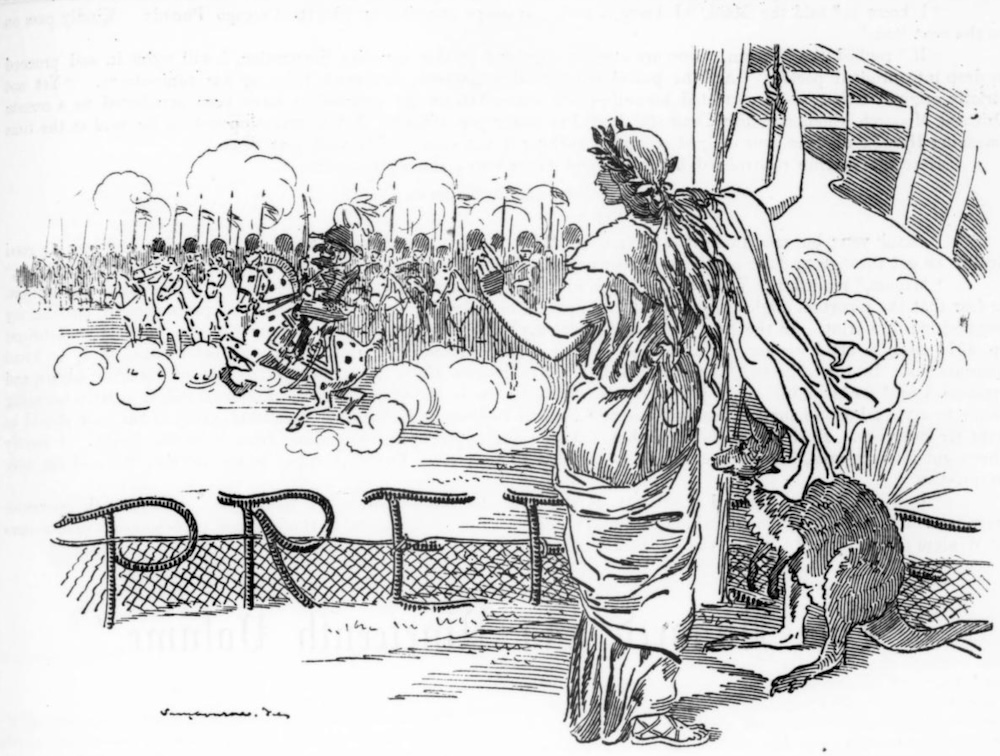

Edward Linley Sambourne's uncaptioned cartoon captures the jubilation with which the Federation of Australia was greeted. Dated "Xmas," it is the opening engraving in Punch on 26 December 1900 (Vol. 119: iii). Here Australia is depicted as "the Imperial Maid," accompanied by her "faithful bodyguard," the kangaroo, as she takes the salute from Mr. Punch, who in turn is accompanied by his orderly — his dog Toby, though not visible in the cartoon — and a whole army of cavalrymen, representing "the flower of Britain's chivalry."

There is a jubilant note here not only because of the imminence of the official inauguration of a federal Australia on 1 January 1901, but because the bitterly fought Boer War seemed to have been largely concluded with the annexation of the Transvaal after the capture of Pretoria — as it happened, a prematurely optimistic view. The word partially seen on the fence in front of Australia might be Pretoria, although this is not explained. However, the immediate cause for celebration was Australia's Federation, and Punch was right to greet it as a milestone:

At the first touch of rosy-toed Aurora, the Imperial Maid had risen to the occasion, the same being unique. Its peculiar features were three; and only two of them could ever meet again. First, it was New Year’s Day; but this recurs, roughly, with every thirteenth moon. Next, it was the opening of the New Century; but every hundredth year we may enjoy the repetition of this splendid event. Lastly, it was the day for proclaiming the Federation of Australia; and this could only happen once in the history of the world.

Fresh from a studied toilette, the Maid emerged into sunlight not more dazzling than herself. The air was heavy with fortunate omens; the soil paved with spotless resolutions. Over these last lightly bounded her faithful bodyguard, the kangaroo, always finding himself in one or other of his elements. Comely by grace of nature, and dressed to distraction, she passed trippingly, yet with majesty, to the playing fields of Mars, a very Atalanta for advance. As she assumed a posture of dignity at the saluting base, the punctual bugle rang; and at the head of his troops forth rode the Veteran of Bouverie Street [i.e. Punch himself]. Traces of pallor shewed about his cheek, for he had seen the New Year in on native Burgundy, a wine that needs its Bush; yet was he full of movement, and mounted on a charger that caracoled superbly.

Behind him marched the flower of Britain’s chivalry, a specimen bouquet of all arms, spared from the long war-harvest, and still leaving a few behind where they came from [the Boer War had entered into its long phase of guerrilla warfare]. Sabre, lance, and cuirass, those discredited tools of a by-gone age, now relegated to pension and pageantry, shone bravely under a dazzling top-light. Onward they came, the thousand and one knights, war-like infants, massed in quarter-column, and not a soul among them seeking cover.

So, with sword at the salute, the Veteran led his legions past our Lady of the Southern Cross.

Some banter follows, and Punch proclaims that little Toby has laid a copy of his speech, uninterrupted by his rather impatient addressee, at her feet as a "New Year's gift" (iv). In the next illustration she is seen reading a scroll entitled "Proclamation."

The "Imperial Maid" had reason to be impatient with his speechifying. Events in Australia were unfolding rapidly now. On Christmas Eve, Edmund Barton (1849-1920), born to parents who had emigrated from England in 1827, and long a dominant figure in the pro-federation campaign, was asked to be the first Prime Minister of this newly unified country. The formation of a federal ministry was announced on 30 December, just after Linley Sambourne's cartoons were published, and just before the official ceremony was due to take place in Sydney.

The inauguration of the new federation was duly celebrated on 1 January 1901. It was a splendid affair that quite outshone Sambourne's imagined one:

At Centennial Park, in the presence of seven thousand invited guests, the imperial troops, a choir of fifteen thousand voices, and sixty thousand spectators, a slight and interesting figure, Lord Hopetoun, came on to the arena to loud and sustained applause. After the choir sang "O God Our Help in Ages Past," and the Anglican primate recited the prayers set down for the occasion, E.G. Blackmore, who had been clerk to the federal convention of 1897-98, administered the oaths of office as Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia to Lord Hopetoun. The choir sang a Te Deum, which because of the terrible heat wafted fitfully around the arena; the flag of the new Commonwealth was hoisted, and the artillery thundered as cheer after cheer ran round the great arena. Then in loud, clear tones Lord Hopetoun read messages of congratulations and hope from the Queen and from the British government. Again cheers resounded round the arena, only to be drowned by the playing of the national anthem, after which the official party retired. So ended the "right and brilliant" inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia. [Hope 171]

For all the euphoria of that day, and for all his own hard work and abilities, Sir Edmund Barton himself is not celebrated wholeheartedly in our own times because of the "White Australia" policy of the period, to which, personally, he was party (see MacCallum 13). Under his leadership, the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 gave the vote "to adult British subjects resident in Australia for at least six months" — but not to "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and African and Asian immigrants" ("Prime Ministers of Australia"). As a result, the placing of the statue shown here on the left has proved controversial. An over-lifesize seated and apparently welcoming figure, the work of the Australian sculptor Carl Merten, it was installed on this bench by Horton Street on Town Green, Port Macquarie, New South Wales, in 2002 to celebrate the centenary of the Federation. But unfortunately it was placed in close proximity to another monument marking the green as an aboriginal burial ground. Many have objected to this insensitive choice of location.

On another matter, that is, in the matter of female suffrage, Barton was untainted by the prejudices of his time. In many ways admirable, he was knighted in Britain in 1902, and received various other honours. By then, however, he was experiencing many difficulties, both personal and political; he resigned in the following year. It had turned out to be rather a brief premiership. Yet Barton's great and abiding achievements — his tireless and successful promotion of the federation during the Victorian period, and his subsequent role as the newly federated nation's first Prime Minister — cannot be gainsaid. These last, in themselves, justify his reputation as the new nation's founding father.

Image scans, text and formatting by the author. Photograph of statue by Philip V. Allingham. You may use the images, and the photograph, without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Clark, Charles Manning Hope. A Short History of Australia. Illustrated Ed. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin, 2001.

"Federation Timeline." Museums of History, New South Wales. Web. 12 February 2026. https://mhnsw.au/guides/federation-timeline/

MacCallum, Mungo. The Good, the Bad & the Unlikely: Australia's Prime Ministers. Collingwood, Victoria: Black, 2012.

"Prime Ministers of Australia: Edmund Barton." National Museuum of Australia. Web. 12 February. 2026. https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/prime-ministers/edmund-barton

Punch, or the London Charavari Vol. 119 (1900) Internet Archive. Web. 12 February 2026.

Sir Edmund Barton. Monument Australia. Web. 12 February 2026. https://www.monumentaustralia.org/themes/people/government---federal/display/22798-sir-edmund-barton

Created 12 February 2026