Click on all the images for more information about them, and to see larger versions of them. — JB

Introduction

Statue of W.E. Forster (1818-1886), who laid the groundwork

for a national system of elementary education.

There was no national system of education in Britain until the year 1870, when William Forster, Liberal Party statesman, successfully guided his Elementary Education Bill through parliament. Children of both sexes from the middle and upper classes were usually taught at home by a governess or a tutor until they were about ten years old, and then only boys continued education in the exclusive public schools, such as Eton, Rugby or Harrow. In the first half of the century schooling for middle- and upper-class girls was normally limited to home instruction provided by parents or governesses, although private girls' schools such as the charitable Cowan Bridge School in Lancashire (immortalized as Lowood in Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre) and Miss Wooler's school at Roe Head, which Charlotte attended next, provided education for a limited number of girls. Generally, upper- and middle-class girls were educated "for the drawing room," whereas boys had the opportunity to prepare for vocations and pursue courses of academic study. The education of girls was particularly unsatisfactory until the late Victorian period, when schools for girls underwent a rapid transformation, which led to an unprecedented increase in the number of females receiving academically-oriented and formalised education.

Accomplishments

Woman Sewing by Thomas Charles Farrer (1839-1891).

When Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, the non-academic education available for upper- and middle-class girls was therefore conducted at home, usually by ill-equipped and untrained parents, tutors or governesses, or at fee-paying boarding establishments. There were a few large schools for girls, and a number of small ones, usually run by a respectable lady and one or two female assistants. Apart from the basic subjects of reading, writing, and arithmetic, these girls were mostly expected to acquire "accomplishments" — domestic skills, such as sewing, embroidery and needlework, as well as drawing, piano-playing, and dancing, French conversation, and the etiquette proper to young ladies. Unlike boys, they were not normally taught science or classics because this was considered too stressful for them, due to their supposed mental and physical frailty. The main aim of girls' education was to inculcate strategies for becoming a good spouse and pleasing a future husband. Female writers and social reformers like Hannah More (1745–1833), Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849) and Emily Shirreff (1814–1897), argued against "accomplishment" education and called for a more serious, academic curriculum for girls (Jordan 440). Of course, there were notable exceptions. Some parents did encourage their daughters' intellectual development, providing them with academic instruction in Greek, Latin, French, Italian, history and philosophy in addition to the usual "accomplishments." Examples of such well-educated girls include outstanding figures such as Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891), or Beatrice Potter Webb (1858–1943).

Sunday Schools

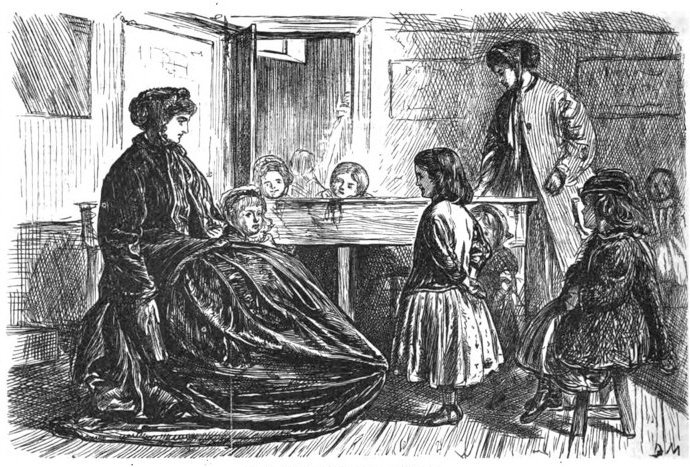

At the Sunday School by George Du Maurier from Punch (16 March 1867): 106.

Provision for educating lower-class girls was more limited. Here, the most important resource was the local Sunday School. The origins of these schools in Britain can be traced back to the late eighteenth century when St. Mary's Parish Church in Nottingham initiated in 1751 Sunday School education for children who were unable to attend a day school due to poverty and long working hours. In the 1780s a few Sunday Schools were established throughout England to teach reading, writing, arithmetic, as well as catechism, to the "deserving" poor. In the Victorian era the number of Sunday Schools rapidly spread all over Britain. These schools therefore provided training in basic skills and religious instruction for poor children and adults of the both sexes who worked from Monday to Saturday and had a day off only on Sunday. Children ranging in age from three years to late teens usually came to a Sunday School after ten in the morning, and stayed till twelve. Then they went home for lunch and returned at one. The school day ended in a visit to church. The children usually left for home at 6 p.m. Teachers in Sunday Schools were often daughters of the local clergy and gentry. The Sunday School was nornmally divided into three divisions: the primary department for the infants; the large middle department, comprised of children between the ages of seven and twelve; and the advanced department, consisting of senior pupils, whose ages ranged from thirteen to eighteen. Religious education was, of course, a core component and the Bible was the basic textbook used for learning to read. Philanthropists and charitable organizations supported the schools financially. The establishment of the Sunday School Union in 1803 contributed to the growth of Sunday and Church Schools. This was not simply an urban phenomenon. In rural counties with a few urban concentrations Sunday School enrolments appear to have been distributed fairly uniformly between city and countryside (Laqueur 53). In 1818, about 4 per cent of the child population attended Sunday Schools (Seaman 20). In 1805, a huge Sunday School was opened in Stockport. It had had 12 large classrooms. According to an 1859 report, it was "the largest Sunday school in the world" (Wright 22). By 1831, some 1,250,000 children of both sexes, i.e. about 25 percent of the population, attended Sunday School. Numbers rose dramatically during the reign. In 1880, there were 550,000 teachers and five million pupils in all Sunday Schools in Britain (Palmer 23). For working-class girls, schooling was, until the vote of 1870 Education Act, mostly limited to Sunday Schools. Nevertheless, and despite being open only one day a week, they contributed significantly to improving literacy among lower-class girls in the early and middle nineteenth century.

Dame schools

In the early nineteenth century, private dame schools with relatively small numbers of pupils in a mixed age group of usually both genders were run by elderly women (school dames), who taught basic reading and writing skills and arithmetic, and provided modest childcare. These schools, whose tradition went back even further than that of Sunday Schools, to the seventeenth century, played an important role in the formation of nursery and primary education in Britain. The dame school was usually run right out of the woman's home. The school charged fees, which, although low (about 3d. a week), excluded very poor children. As well as the basics, girls of a better class might learn needlework, music, dancing, drawing and other accomplishments designed to impress prospective husbands. There was little control over the quality of teaching and some dame schools were run by almost illiterate teachers, whereas others provided quite a good basic educational foundation. In the 1830s and 1840s, dame schools began to decline in numbers with the appearance of new types of schools. Eventually, after the introduction of compulsory state elementary education in 1870, dame schools almost disappeared in England .

Charity Schools

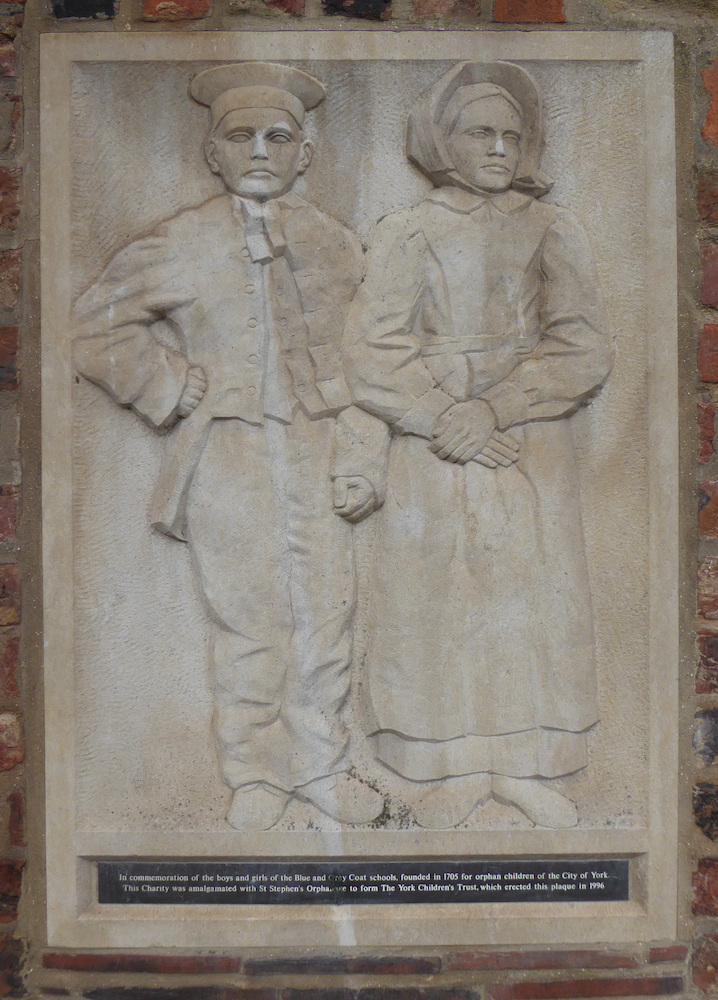

Plaque in Commemoration of the boys and girls of the Blue and Grey Coat schools founded in 1705 for the orphan children of the city of York, near an entrance to St Anthony Hall's garden, York.

During the early Victorian period, some working-class girls attended charity schools maintained by voluntary or charitable societies managed by Anglican or Nonconformist groups, such as the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the National Society and the British and Foreign Schools Society. Funded by private donors, these schools followed a curriculum which again included the skills of basic reading and writing, as well as moral and religious education (Bible-reading), but also, from the 1840s, geography and history. Mostly concentrated in towns, these schools provided pauper boys and girls with free basic instruction of a slightly wider range. Learning was usually accomplished by rote memorization, i.e. children chanted basic concepts over and over again until they knew them by heart. Lower middle-class girls could attend a charity school from the age of ten. Charity schools, which dated back to the late seventeenth century, also contributed to the formation of nineteenth-century public primary education in England and Wales. Some of the most famous charity schools included Cowan Bridge and Roe Head, as mentioned above, and the Blue Coat School in Westminster. In York alone several such schools operated: the Grey Coat Charity School for Girls, the Spinning School for Girls, the York British Girls School, and the Quaker Trinity Lane Girls School. In Manchester, five Anglican charity schools for girls were established.

Ragged and Industrial Schools

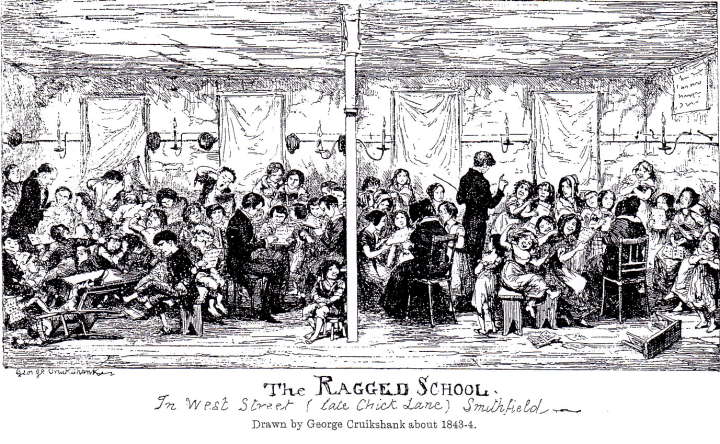

The Ragged School / In West Street (late Chick Lane) Smithfield by George Cruikshank, 1792-1878.

Ragged schools were another type of charitable schools dedicated to the free education of poor children of both sexes in Britain. The first ragged school was started by John Pounds, a Portsmouth cobbler in 1818. Soon Pounds' idea of free schooling for working class children found many supporters in both Scotland and England. In 1841, Sheriff Watson established the Aberdeen Ragged School for boys who lived in great poverty. A similar school for girls opened in 1843, and a mixed school in 1845. In 1844, Lord Shaftesbury formed the Ragged School Union (Seymour 4). The idea of ragged schools was to educate destitute and neglected children of the both sexes and incorporate them into society. Wealthy individuals gave considerable sums of money to the Ragged Schools Union, which helped to establish some 350 ragged schools in London and over 100 in provinces by the time the 1870 Education Act was passed. Apart from a basic education they provided some craft training for boys and domestic skills for girls, such as knitting, sewing, spinning and housework, including laundry. Between 1844 and 1870, the number of ragged schools grew steadily. Charles Dickens, who visited the Field Lane Ragged School in Holborn, London, in 1843, was initially sceptical about their aims, but eventually donated some funds for maintaining them.

The London Mechanics' Institution in Southampton Buildings, Chancery Lane, its home from 1825-1885.

The ragged school movement was also involved in the development of industrial schools. In 1844, the Liverpool Mechanics' Institution opened a school for the daughters of tradesmen, clerks and shopkeepers. Between 1847 and 1883 Huddersfield Female Educational Institute provided evening classes to girls and young women. This is regarded as one of the first such institutes for working-class women in Britain. In 1854, the Leeds Mechanics' Institute founded a similar Ladies' Educational Institution which gave a practical education (equivalent to that in the "modern" or "commercial" schools of the time), and included as well as the basic subjects, classes in accounts and book-keeping (Avery 63).

Secondary Education for Girls

After the Education Act of 1870, elementary education for both sexes became compulsory, but few girls had the opportunity to enter into secondary education as most families preferred their sons rather than their daughters to pursue a more advanced education.

It was still the purpose in educating women to keep them in their role as the domestic middle-class wife and mother. John Ruskin believed that a woman's education should be such that it should "take into consideration a husband's need to share his interest with his wife and conduct intelligent conversation with her." [Levine 30]

As a rule the girls' secondary schools lagged far behind boys'. There were several notable exceptions, like Cheltenham Ladies' College, established in 1854, which started off as a day school with a boarding house for girls who lived too far away to attend daily. From 1858, its headmistress was the feminist, Dorothea Beale (1831–1906). She modified the traditional female-oriented curriculum, which basically consisted of needlework, music, dance, and domestic skills, by introducing courses such as English, French and German, mathematics, history and physical geography. She contributed significantly to reforms in women's education in Britain. Cheltenham Ladies' College became a leading secondary education institution throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1850, Frances Mary Buss (1827–1894), a pioneer in women's education, and her mother founded in Camden Town the North London Collegiate School (NLCS), a fee-paying day school which offered girls of the professional classes an education of the same standard as that of middle-class boys. The school's ethos marked a departure from the middle-class tradition of home-schooling girls with an emphasis on social accomplishments, with less time devoted to the development of intellectual activity. The NLCS served as a model for girls' secondary education. The City of London School for Girls (CLSG), established by the Corporation of London in 1894 in Carmelite Street near the Victoria Embankment, provided — apart from religious instruction — literary education and "all other useful learning" (Avery 40). After 1871, the National Union for Improving the Education of Women of All Classes significantly contributed to the establishment of a number of secondary schools for girls. Maria Grey (1816–1906), one of the founders of the Girls' Day School Trust, called for giving the same educational opportunities to men and women in a speech to the Society of Arts in 1871. On her initiative, the Girls' Public Day School Company established 38 day schools for girls throughout Britain.

Women's Colleges

Female student at the one of the corners of the base of the Founder's Statue, Royal Holloway.

In 1849, Elizabeth Jesser Reid (1789–1866), a social reformer, opened Bedford College in London as the first higher education college for women in the United Kingdom. The College offered teacher training from the 1890s for women students. However, female students could not obtain degrees until 1878, when the University of London first allowed women to graduate. In the 1890s, the College also began to offer courses in public health and hygiene, which allowed the alumnae to find employment in public health inspection. Among its early students and supporters were Barbara Leigh Smith (later Bodichon, 1827–1891), the philanthropist and campaigner for women's property rights and later founder of Girton College, Cambridge; Bessie Rayner Parkes, (1829–1925), the feminist and campaigner for equal opportunities for women in education and employment; the novelist George Eliot; and Sarah Parker Remond (1826–1894), the American black activist and abolitionist campaigner. Another early student was Dickens's thirteen-year-old daughter Katey, who attended drawing classes in 1853–1854. The College became a constituent part of the University of London in 1900, and finally merged with Royal Holloway College in 1985. In 1869, the Watt Institution and School of Arts in Edinburgh, a predecessor of Heriot-Watt University, began to admit women students. Other colleges for women in Edinburgh included the Edinburgh Ladies' College and George Watson's College for Ladies. At St. Andrew's University a college for girls was established in 1877. Women's colleges were also established at Oxford and Cambridge in the 1870s, where younger women sought to get better education and more economic and social independence. Girton College, originally a college for women, opened in Cambridge in 1869. Other women's colleges included Newnham College, founded in 1871, Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville Hall, opened at Oxford in 1878 and 1879 respectively, followed by St Hilda's College in 1893. In 1874, the London School of Medicine for Women was founded, becoming the first medical school in Britain to train women. In 1876, University College, Bristol (now the University of Bristol), opened as the first co-educational university college in England, although it did not have the right to award degrees. During this college's first year, 99 day students (30 men and 69 women) registered, and the number of evening students was 238 (143 men and 95 women) (Sherborne 3).

Entering the Professions

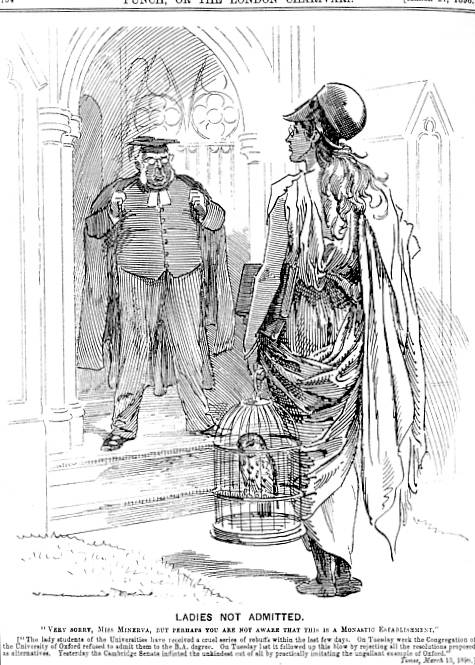

Ladies not admitted — a cartoon by Linley Sambourne in Punch, 21 March 1896, p. 134. Right: Twenty-first century women graduates on the way to their graduation ceremony at Royal Holloway, University of London.

In the early Victorian period, universities were exclusively a male preserve which provided a professional education for lawyers, doctors, the clergy and secondary-school teachers. All these professions were closed to women. As early as 1833, the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution opened its classes to women. In 1848, Queen's College in London offered an improved system of education for future governesses who wanted to receive professional certificates. Soon the College extended its educational offer to women who did not necessarily wish to become governesses. Among its early alumnae were two important educationists already mentioned, Dorothea Beale (1831–1906), the suffragist and educational reformer, later principal of the Cheltenham Ladies' College, and Frances Mary Buss, founder of the North London Collegiate School for Girls. In 1878, London University became the first university in the United Kingdom to admit women to two colleges: Bedford College and Royal Holloway College, allowing these colleges to award degrees to women on exactly the same terms as to men. In 1880, first four women gained BA degrees at the University of London. However, most Oxford and Cambridge colleges held out against women until the next century. Despite gaining more educational access, women were not granted degrees at the two most prestigious universities in England until the twentieth century (1920 at Oxford and 1948 at Cambridge), although Scottish universities, such as the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow, allowed women graduates in the late nineteenth century. The Edinburgh Seven were the first group of matriculated undergraduate female students who began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869, but were prevented from graduating and qualifying as doctors, although their campaign to grant women the right to become doctors gained national attention and won them many supporters among prominent physicians and scientists, including Charles Darwin. In the later 1870s, five of them earned their degrees abroad. In 1886, Dr Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake (1840–1912) established the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. She was the first female physician in the city. In 1894, Marion Gilchrist was the first woman to graduate from the University of Edinburgh, and the first woman in Scotland to graduate with a medical degree, despite the fact that medicine was considered an 'unfeminine' subject at the time.

Conclusion

During the late nineteenth century, education for middle- and upper-class girls underwent significant transformations in Britain, leading to an unprecedented increase in the number receiving an academically-oriented education. This educational shift brought them in line with their male counterparts, enabling some girls to pursue higher education and gain access to previously unattainable careers. Simultaneously, changes in labour laws and education reforms greatly improved access to schooling for working-class girls. These reforms standardized the educational curriculum for girls and allowed them to remain in school for a longer periods compared to their early Victorian counterparts. At the close of the Victorian era, an increasing number of middle- and upper-class girls and women attended schools and colleges with a curriculum similar to that in boys' schools and some of them even attained university education. Instead of going into poorly paid domestic service, more women were able to take up a range of jobs, from shop assistants to telegraph clerks at one end of the scale, to professions like teaching and medicine at the other.

Links to Related Material

- Primary and Secondary Education in England and Wales, 1850-1876

- Ragged Schools

- Queen's College and the "Ladies' College"

- The University of London: Opening the Doors of Higher Education

- The University of London and Women Students

- Archival Resources Relating to the Higher Education of Women in England

- Nineteenth-Century Education, Theory and Practice: A Bibliography

Bibliography and Further Reading

Avery, Gillian Avery. The Best Type of Girl: A History of Girls' Independent Schools. London: André Deutsch, 1991.

Barnard, H.C. A History of English Education, from 1760. 2nd edition. London: University of London Press, 1961.

Blackmore, Jill. Troubling Women: Feminism, Leadership and Educational Change. London: Open University Press, 1999.

Bryant, Margaret E. The Unexpected Revolution: A Study in the History of the Education of Women and Girls in the Nineteenth Century. London: University of London, Institute of Education, 1979.

Burstyn, Joan N. Victorian Education and the Ideal of Womanhood. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1980.

Busher, Hugh. Education since 1800. London: Macmillan Education, 1986.

Clarke, A. K. A History of Cheltenham Ladies College. London: Faber and Faber, 1953.

Cliff, P. B. The Rise and Development of the Sunday School Movement in England 1780–1980. Redhill: National Christian Education Council, 1986.

Copelman, D. London's Women Teachers: Gender, Class and Feminism, 1870-1930. London: Routledge, 1996.

Digby, Anne, and Peter Searby. Children, School, and Society in Nineteenth Century England. Macmillan, 1981.

Dyhouse, Carol. Girls Growing Up in Victorian and Edwardian England. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981.

Higginson, J.H. "Dame Schools", The British Journal of Educational Studies , Jun., 1974, Vol. 22 (2) (Jun., 1974): 166–181.

Jordan, Helen. "'Making Good Wives and Mothers'? The Transformation of Middle-Class Girls' Education in Nineteenth-Century Britain", History of Education Quarterly, Winter, 1991, Vol. 31(4) (Winter, 1991): 439–462.

Kamm, Josephine. Hope Deferred: Girls' Education in English History. London: Methuen, 1965.

Laqueur, Thomas Walter. Religion and Respectability: Sunday Schools and Working-Class Culture 1780 –1850. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1976.

Levine, Philippa. Victorian Feminism 1850-1900. Gainesville, FL: Univ. Press of Florida, 1994.

Jones, M. G. The Charity School Movement. London: Cassells, 1964.

Martin, J. Women and the Politics of Schooling in Victorian and Edwardian England. London: and New York: Leicester University Press, 1999.

Palmer, John. The Sunday School. Its History and Development. London: Hamilton, Adams & Co., 1880.

Prochaska, Frank. Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-Century England. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Sanderson, Michael. Education, Economic Change and Society in England 1780–1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Seaman, L.C.B. Victorian England: Aspects of English and Imperial History 1837–1901. London and New York: Routledge, 1973.

Seymour, Claire. Ragged Schools. Ragged Children. London: Ragged School Museum Trust, 1995.

Sherborne, J.W. University College Bristol 1876–1909. Bristol: The Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, The University of Bristol, 1977.

Stephens, W.B. Education in Britain 1750–1914. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

Wright, J.J. The Sunday School: Its Origin and Growth. London: The Sunday School Association, 1900.

Created 14 December 2024