he story of the serial killer known as ‘Jack the Ripper’ is one of the most famous narratives in the history of crime. In the weeks between 31 August and 9 November 1888, the unidentified murderer terrorized the streets of Whitechapel in the poverty-stricken East End of London and butchered five women, all of them prostitutes. He was never named and never caught, but his grotesque sobriquet – which was (probably) coined by an unidentified journalist (Oldridge 47) – has long been used as a moniker for depraved, sexually motivated killing and urban horror.

The Metropolitan Police of 1888 were clueless as to whom the perpetrator might be, and despite a wide-reaching investigation were never able to identify a plausible suspect. In an age before forensic science or electronic surveillance and a limited capacity to synthesize diverse reports, the Police had no means of nailing their man, and when the murders ceased the case was closed.

Further investigations, of a sort, have been left to generations of modern ‘Ripperologists’ who have advanced numerous theories – some convincing, some absurd: a vast field of speculation that blames everyone from William Gull, the Queen’s surgeon (Stephen Knight) to the singer Michael Maybrick (Bruce Robinson) and the artist Walter Sickert (Patricia Cornwell); sundry others, such as Aaron Kosminski, a hairdresser, and even Lewis Carroll, are also in the frame. These accusations are embedded in conspiracy theories of establishment cover-up and deception, with the Freemasons, especially, being the target of dubious or extravagant claims. The accounts are fascinating in their own right, if only for their intricacy, but after so many years the case is stone cold: no-one will ever establish the Ripper’s identity, and further investigation only leads to ever more improbable solutions.

Two examples of modern "Ripper" books.

More productive, given the impossibility of closure, are scholarly approaches which have interpreted the Whitechapel murders in the context of late Victorian culture. In this reading, as formulated by historians such as Judith Walkowitz, the Ripper is refigured as a symbol of Victorian values, anxieties, sexual and racial prejudices, the class struggle, the distrust of authority, and the processing of information. As Clive Bloom explains, the phenomenon known as ‘the Ripper’ is emblematic of its time, essentially a ‘legend’ around which a ‘constellation of historico-psychological notions … have gathered’ (91). For sure, the Ripper was not just a person but a culturally constructed phenomenon, an embodiment of social fears and a product, as we shall see, of the media and its negotiation of the truth.

To decode and explain the Ripper becomes in this context a matter of reading his social and cultural significance, and a large body of modern literature has focused on aspects of his status as a totemic trace. Most of those investigations have concentrated on the written word – particularly as they featured in the gutter press and in governmental and police reports. It is important, however, to note that little attention has been directed at the many visual representations of the murderer and his crimes. These images, which appeared in the illustrated press, are important because they too act as representations of Victorian attitudes as they were crystallized in the Ripper phenomenon. Decoding these visual signs tells us much about those ideas and understandings as the written evidence, and it is interesting to shift focus from the diffuse and extended speculations in words to the registration of those meanings in graphic designs. I would contend, further, that they sometimes help to shape the Ripper’s peculiar significance and to help us to understand Victorian attitudes that are not always clearly expressed in a written form.

Picturing the Crimes: Sensational Storytelling

Making sense of serial murders is problematic because it is not always clear if the crimes are in fact part of a sequence or even the work of one hand. In the Ripper’s case his grisly oeuvre is especially contentious: although five ‘canonical’ murders have been identified, women were killed in the same manner before and after the ‘official’ period of the criminal’s activity. His reign of terror was constructed out of similarities in the style of the killings – although there were variations which suggest that the pattern was not as clearly defined as one might expect.

Nevertheless, the original Victorian audience expected to learn of the Whitechapel murders in terms of an established narrative. Alexandra Warwick contends that the Ripper crimes were constructed textually, with connections made and stories assembled out of disparate parts. This structure notably took the form of serial publication as the murders were committed and the public consumed the crimes as a series of events (71–72). The agents of this construction were of course the newspapers (which published lurid instalments) and especially pictorial journalism. As Warwick continues, the ‘press, and particularly the more sensational publications, carried many illustrations [which] took the form of a page or a strip of drawings with captions’ (72). It was these designs, appearing in The Illustrated Police News, The Pictorial News and The Penny Illustrated Newspaper, which crystallized the notion of serial killing as quite literally a serial or narrative which enshrined ‘the rhythms of repetition’ (Warwick 72) that were so much a part of Victorian understandings of how reality might be assembled.

This type of visual story telling is epitomized by the reporting of the death of Elizabeth Stride on the front page of the Illustrated Police News. Drawn by an anonymous artist, this composition is presented as a tiered arrangement in which the focus is a portrait of Stride as she was alive, with framing scenes on either side and below. The effect is sensational, presenting the recent present – Stride’s murder – with that event being placed within a story, with other episodes showing the previous homicide of Catherine Eddowes, who was murdered nearby the same night. This arrangement works, in other words, to forge a link between what is and what has been within a narrative flow. The captions act as prompts and the whole design acts a concise epitome, endowing events with the clarity of a comic strip.

Two front pages from The Illustrated Police News, reporting (left) on the death of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes; and (right) Mary Kelly. Each is a dense pictogram of information – and speculation.

Such narrativizing makes connections as if the crimes were part of a plot and figures them in a pattern that alludes to the staccato, episodic rhythms of the Victorian novel and is explicitly linked to the structure of Sensational fictions by Wilkie Collins, Charles Reade and M. E. Braddon. More especially, this mode of telling invokes the Hogarthian ‘progress’ in which a character moves from virtue to vice, as in The Rake’s Progress (1732–4), or here, from one grisly homicide to the final horror of Mary Kelly’s murder. It also deploys a well-established mode of visualizing iniquity as it was developed in images by George Cruikshank, such as The Folly of Crime (1845). This narrative of compartments provides a prototype for the sort of visual storytelling that was applied to the real-life career of the Ripper.

Cruikshank’s The Folly of Crime, the moralizing pictorial

narrative that models for reportage of the Ripper.

The sensational front pages on The Illustrated Police News draw on this discourse and act to reinforce prevailing notions of how such events should be conceptualized. More than this, I think the visual montage influenced the way in which the Victorian audience made sense of the unpredictability of having a homicidal maniac on the loose: by converting the murders into a narrative it becomes possible to asset a degree of control, if only because all stories must have an end. The Pall Mall Gazette and other sensational newspapers such as The Star constantly wondered when the Ripper would next strike, but the visual front covers of The Illustrated Police News were both a lurid exploitation of suffering and the promise, as in Hogarth’s story-telling and Cruikshank’s Folly of Crime, that the criminal would eventually be caught and the murders concluded – a resolution half-achieved.

Poverty and the Ripper

The Ripper and his crimes were a focus of bourgeois anxieties about the impact of poverty and the idea that the suffering of the poor could lead to social upheaval, the collapse of order, and even revolution. The Ripper became in this sense the embodiment of social fears, a Gothic monster whose symbolic significance went well beyond his immediate impact.

The connection between poverty and fear of social unrest was widely expressed in contemporary literature and is epitomized by E. J. Milliken’s doggerel to accompany John Tenniel’s Blindman’s Buff [sic] in Punch (22 September 1888). Directly addressing the Ripper phenomenon, Milliken offers a lurid, sensational commentary on the conditions of life in Whitechapel, which he describes as a ‘slime-fouled … Ghetto,’ a ‘swamp’ where ‘well-armed Authority fears to tread’ and ‘Ruthless red-handed Murder sways the scene.’ Here, the poet says, is the Ripper’s natural domain, a place of ‘hags called women’ and ‘ghouls in the guise of men’, those ‘carnivores of crime’ who threaten, despite their natural home among the ‘vermin of vice’ (138), to corrupt society as whole.

Doré’s views of a squalid, reeking London, with its poverty and tovercrowding. It looks much like his version of Hell – perhaps deliberately.

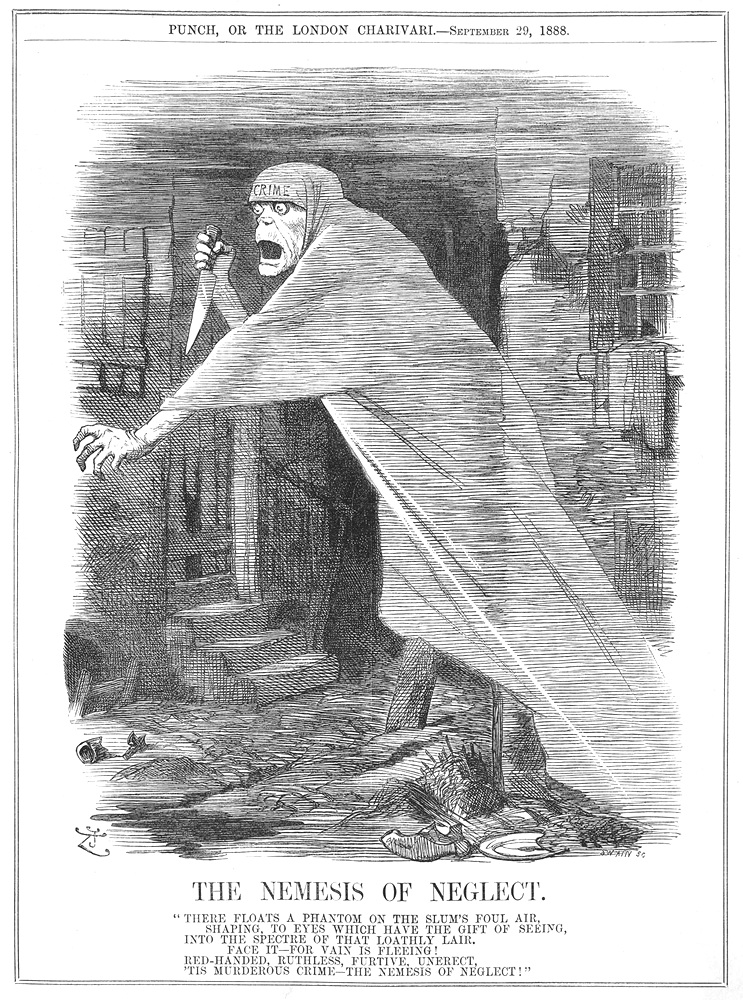

The writing is powerful in its crude excess and Tenniel makes its message entirely clear in his cartoon by showing a policeman engaged in an impromptu game of blindman’s bluff: surrounded by degenerates who have bestial physiognomies, he has little chance, the artist implies, of finding the Ripper; immersed in filth, crime, and the sort of urban decay that can be seen in Gustave Doré’s London. (1872), the officer’s task is probably impossible. Tenniel’s grim humour catches a sense of the panic of those who berated the police for not catching the culprit, but the artist goes much further in The Nemesis of Neglect (22nd September 1888). In this design Tenniel encapsulates contemporary fears by explicitly converting the Ripper into an emblematic type: the recent murders are referenced in the holding of the knife, but the figure has become a ghoul symbolizing all crime as he arises from the squalor of Whitechapel. Tenniel’s cartoons act, in short, to crystallize the idea of the Ripper as the embodiment of a generic murder and outrage. Acting as a development of the literature, his images give the Ripper an ever-greater status as a subversive power.

Left: Tenniel’s Blind Man’s Buff, and right, the same artist’s Nemesis of Neglect. Both cartoons reveal the Ripper’s emblematic significance as the symbol of social degradation.

Representing the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was mythologized to become a sort of urban bogeyman who recalls Spring Heel’d Jack, an eighteenth century spectre who supposedly stabbed women and, like his Victorian descendant, could always evade capture. Both figures, indeed, could vanish: Jack of the heels by jumping over high fences, and the Ripper by disappearing into the darkness.

Seemingly invisible, the Ripper’s appearance was debated as the police sought to identify a suspect, with many eye-witness reports of suspicious individuals providing the basis for widely varying descriptions. Sometimes he was short, sometimes tall; sometimes fair, sometimes dark; a gentleman or a labourer; wearing dark clothes or a light jacket; hatless, or sporting a sailor’s cap. The list was endless and always inconclusive.

Speculation was focused, in line with contemporary theories of the body as a text, on how his manner and face might represent a wicked character. Gait was viewed as an important sign embodied in the concept of ‘moving suspiciously,’ an idea difficult to define but one which informed written and visual representations and was central to pictorial images. Each criminal, one theorist observed, will ‘have their own peculiar walk’ (Rogerson 3); and in at least one design from Illustrated London News we have an image of how the Ripper might move in the form of a man shuffling along with his hands in his pockets.

A section from H. G. Sepping-Wright’s Sketches with the Police, which shows a seedy character hurrying away from one of the groups of vigilantes who patrolled the streets as the Police failed to make progress.

However, the most telling visual information was always going to be in the form of the Ripper’s face. In an age when visuality was central part of its culture and looking and seeing a crucial currency of exchange, there was a ‘persistent desire,’ as Craig Monk observes, ‘for a definitive image of the killer’(91). The Police were desperate to establish a likeness and that imperative often took a bizarre turn: for example, Annie Chapman’s eyes were photographed by the Police in the misplaced belief that the killer’s semblance would be imprinted on her retina (91) as her last sight before she died.

.More to the point, it was believed that the Ripper’s face was a signifier which, decoded correctly, would reveal his guilt. This concept was informed by the pseudo-sciences of physiognomy and pathognomy, and was widely believed that there was such as thing as a ‘criminal face’ (Cowling 284–316). Always, it was argued, ‘Certain forms of crime will have a certain form of face’ (Rogerson 3). One reporter, having interviewed several prostitutes, came up with a portrait which would clearly indicate the murderer’s black heart: ‘His expression is sinister … His eyes are small and glittering. His lips are usually parted in a grin which is not only not reassuring, but excessively repellent … ‘(Oldridge 52). It is of course subjective, naive nonsense, the stuff of Gothic novels and Penny Dreadfuls, but it represented a significant part of the Victorians’ attempt to conceptualize unspeakable horror and alienating strangeness.

Signifying, or trying to signify, in the context of the unknown, the Ripper’s appearance was also nuanced by racial considerations. As critics such as Sander L. Gilman have pointed out, perceptions of the Ripper were rotten with xenophobia and fear of the racial Other in a period when the East End had a large population of immigrants, and it was widely assumed that the murderer was – and would look like – a foreigner; after all, it was reasoned, such ghastly crimes were outside the domain of decent Englishmen. Those most under suspicion were the Jews who constituted a significant proportion of Whitechapel tradesmen, and descriptions emphasized what were perceived to be a Jewish appearance. The suspect with the glittering eyes, the Victorian reporter notes, was undoubtedly ‘a Jew or of Jewish parentage, his face being of the marked Hebrew type’ (Oldridge 52). This ‘marked type’ is of course illusory, but antisemitic racial stereotypes were reinforced by such written accounts and were given an added directness and intensity in the illustrated press.

Three representations of the ‘Jewish type,’ each taken from the front cover of The Illustrated Police News. The image is purely stereotypical and owes more to racist folklore than reality: a perfect bogeyman, a dark man who lurks in the darkness, and is invariably a murderer and/or a sexual predator.

Indeed, the picturing of Jack in The Illustrated Police News materialized and focused the notion that the murderer must be a type of depraved Jew, rendering his face in terms of time-honoured stereotypes which emphasise the hooked nose, glaring eyes, dark colouring, and facial hair. Such images provided a material representation, a sort of ‘wanted’ poster that was carried into the readers’ homes. The same can be said of an image by Tom Merry in Puck. It is noticeable that of the six pictured faces half are foreign caricatures and could be ‘Hebrews.’

Multiple representations of the Ripper, in Puck (September 21 1889). Produced almost a year after the murders. The arbitrariness of the portraits makes a telling comment on the inadequacy of the Police, who were unable to fix on a single likeness.

Such picturing amplified public prejudices, and that prejudice could also be described, in modern terms, as ‘institutional racism.’ Of the more than a hundred suspects interviewed by the police, a large portion were Jewish, and the notion of Ripper being Jewish was reinforced by the discovery of the so-called ‘Goulston Street graffito.’ This message was found on a wall near to the murder of Catherine Eddows: ‘The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ It makes no sense and, as a riddle using a double negative, could barely be described as evidence of Jewish involvement – what Jew would misspell ‘Jews’? Or was it written by a gentile to claim the crimes were by a Jew? But it was enough for Sir Charles Warren, the Chief Commissioner of Police, to order it to be effaced for fear that it would stimulate anti-Jewish riots.

Writing and Visualizing the Victims

The story of Jack the Ripper has stressed the mythopoeic status of the anonymous murderer whose savage bloodlust was unpunished as he tormented the police and terrified the public. Most attention has been directed on trying to identify the killer, and relatively little on those he killed. Hallie Rubenhold has offered a sympathetic account of the ‘canonical’ five victims in a recent study, but Victorian attitudes to the murdered women were far from compassionate.

Victorian notions of the victims were generally informed with moralism, sexism, and class-prejudice. There was sparce sympathy among the bourgeois public for women who were of a ‘low’ moral character, the exemplars of taboo, Punch described the prostitutes as ‘hags called women’ (‘Blind Man’s Buff,’ 138) and for the readers of The Pall Mall Gazette they were simply ‘wretched’ (‘Another Murder,’ 1). Their status as individuals offering an immoral service was compounded, moreover, by their position at the very bottom of Victorian society: prostitutes were despised. There was nevertheless a salacious interest in the manner of their deaths and the nature of their injuries, and several modern critics have interpreted this fascination in terms of voyeurism as male observers objectified the bodies of what were supposed to be highly sexualized women. L. P. Curtis exaggerates the case when he notes that ‘male readers of the Ripper news could hardly avoid fixating on the bodies of the victims ravaged by the phallic knife’ (214), a claim that sounds like a tired feminist cliché. But there is no doubt that the writing of the women’s wounds was both explicit and sensationalized, converting the all-too-pathetic victims into Gothic bodies, intriguing objects of horror which connected sex, violence, and death.

Such carnography is typified by the Pall Mall Gazette’s reporting of the crimes. Of Polly Nichols’s injuries the writer notes with relish how the ‘ferocious character of the wounds’ meant that the ‘throat was cut from ear to ear’ and goes on to specify the damage, which must have been done by a butcher’s knife (‘Polly Nichols,’ 9). Even worse – and more sensational – was the final condition of the ‘ripped-up’ Catherine Eddowes, who is described as a piece of meat in direct allusion to the idea that the Ripper could be a butcher: ‘Short of absolutely skinning his next victim, it is difficult to see what fresh horror is left for him to commit’ (‘Number nine,’ 10). Such callous commentary played to a certain sort of audience, and it is even possible that the Ripper took the Gazette’s remark as a suggestion, and indeed went on to skin his final victim.

This type of body-horror was again inflected with racism. Jewish butchers were suspected since they were supposed to kill animals in a particularly brutal way, and the damage done to the women’s bodies was viewed the work of uncivilized men whose grisly work displayed a ‘Red Indian savagery’ (‘Another Murder,’ 1). Repelled by the notion of a home-grown maniac, readers wrote to the press suggesting all sorts of Johnny Foreigners, with one suggesting that the murderer was a Malay sailor, since ‘the Malay race are extremely vindictive, treacherous, and ferocious’ (‘Is the Murderer a Malay?’ 1–2). As public hysteria grew it must have seemed that every foreigner was a suspect.

In every case, the written reporting of the crimes left nothing to the imagination, but visual representations are more complex, with two types of pictorial information being created: the official photographs taken by the police in an age when forensic science was in its infancy, and the wood engraved illustrations which appeared in The Illustrated Police News and The Penny Illustrated Paper.

The first of these post-mortem images reflect a curious indeterminacy about their function. Intended to help provide the investigators with clues, three of the five photographs are merely portraits of the dead women’s faces with their eyes closed, and do not show their bodily injuries. In a provocative feminist reading, Megha Anwer argues that the photographs reflect male prejudices about the status of the women by showing them as if asleep – a visual representation that comments on their role as prostitutes by linking sleep with ‘sleeping around’ (434). Anwer further suggests that the portraits are like mug shots, a visual trope which identifies each woman as a perpetrator, not a victim, and implies that they were somehow responsible for putting themselves in the way of danger.

Police photographs of two of the Ripper’s victims, as if asleep: a) Annie Chapman. (b) Elizabeth Stride. Both these images are in the Public Domain.

Such arguments are interesting but overplay the significance of the portrait format. A likelier explanation is that the police were unsure, at least for the first three murders, of the value or significance of making a visual report. Such photographs were intended, after all, to identify the victims for the public – showing their terrible injuries was not considered appropriate given that it would only generate panic, and apart from keeping their eyes open it is hard to see how they can be shown as anything other than being asleep. In this configuration, they are simply depicted in the terms of the post-mortem photography that was popular at the time, and of limited value as a means of understanding the crimes. However, the police did take full body shots of two of the victims as evidence – Eddowes and Kelly. These, for the first time, give a sense of the extent of their injuries. The Eddowes photograph represents the poor victim once she was stitched up by the pathologist, a terrible portrait of suffering, although it does not convey the condition of her body when it was found; that was recorded in an on-the-spot sketch. The only photograph to suggest the full extent of the Ripper’s butchery is the image of Kelly, which provides more than enough grotesque information about the dismantling of her body.

The gruesome photographs of the Ripper’s pathetic victims: left, Catherine Eddowes, and right, the remains of Mary Kelly. Both these images are in the Public Domain.

Neither of these photographs was released to the general public and only appeared in print some years after the event. Nor was it the case that the images appearing in The Illustrated Police News were any more revealing. Instead, the faces of the women are shown as portraits of them in death with what appear to be minor abrasions to their faces.

Polly Nichols, as reported in the press.

We can see, in short, that pictorial representations of the victims act in a way that is contrary to the general trend of visualization, which usually works to reveal, clarify or crystallize Victorian attitudes to the crimes. Here, though, the sight of ‘ripped-up’ bodies was beyond the bounds of Victorian propriety and the full range of the terrible injuries was suppressed or withheld from the process of picturing. These, it seems, were crimes that could be described in a written form, but not in the raw, blunt language of visual art. It was interesting to read of the crimes, but not to see them. For once, the process of showing kept the reality at arm’s length.

The Ripper, Sensationalism, and Exploitation

Recent historians such as Curtis have described the Ripper phenomenon as a media event which was constructed, to a large extent, by the tabloid press. The Ripper’s meanings were culturally constructed, but the fascination with his crimes was carried forward by the need for copy – for news that would intrigue and continue to engage the reading public.

The best way to achieve that effect, then as now, was to present the news sensationally. The Whitechapel murders were a ghastly reflection of the social conditions and values of the time, but for the editors of the tabloids they could be re-branded as Gothic horror, lurid excess, sex, scandal, and social taboo. As noted earlier, it is well known that a good part of the ‘coverage’ was based on fake letters written by journalists which were knowingly presented as genuine; whenever interest was flagging, new missives, with terrifying messages, were used to stimulate the readership. Many letters were from cranks, but these too were presented as if they were genuine.

Visual material was similarly used, as we have seen, to present the murders in an exciting way which linked to Sensational plots; picturing the crimes in an episodic form also linked to the traditions of the Newgate novel and the Penny Dreadful. To the modern eye, the front pages of The Illustrated Police News look like a comic strip or a graphic novel – and this, essentially, is what they are: pictorial epitomes intended for rapid consumption, with the montage of vignettes acting to present a sort of fast-moving, visceral experience, akin to the pace of a modern cinematic thriller, in which the reading eye is offered the instant gratification associated with scandal and horror.

In it interesting, moreover, to see how individual scenes are designed to evoke a horrified response by drawing on a series of iconographies. One of these is the gestural language of the melodramatic theatre, so that each scene is figured as an expressive unit in which the characters finding the bodies freeze into horrified attitudes, often with hands raised, and with staring eyes. This expressive convention is applied to images appearing in all of the pictorial tabloids and even the more respectable Illustrated London News. Gothic semiotics are similarly deployed, and it is noticeable that illustrators play on the crimes’ nocturnal settings by showing the bodies surrounded by threatening and suggestive shadows that owe as much to the Gothic novel as they do to the under-illuminated backstreets of Whitechapel.

A sensational, Gothicizing iconography made up of atmospheric lighting and melodramatic acting. a) from the front cover of The Illustrated Police News (13 September 1888), which shows the finding of Catherine Eddowes; b) from the cover of the same newspaper, with the discovery of Annie Chapman’s body (15 September 1888); and c), a policeman finding the remains of Mary Anne Nichols in The Penny Illustrated Newspaper (8 September 1888).

The pictorial reporting of the Ripper’s activities are thus mediated through the lens of sensationalizing visual languages which act to frame the murderer, once again, in the terms of a mythologized bogeyman. The Ripper becomes a Gothic monster, the property of stage and page, and two effects were produced: on the one hand, the crimes were amplified, made to seem ever more sensationally dreadful; on the other, they acted to control and moderate the reality, essentially to distance the Ripper from the public by turning him into a sort of literary or mythological figure, an emblematic Death rather than a real person; indeed, in one cartoon in The Illustrated Police News he is shown in exactly these terms, as the Grim Reaper. This ambiguity added to the complex responses to the Whitechapel murders. The Ripper embodied contemporary anxieties, but he could be controlled by being turned into a legend, a cipher rather than a maniac whose motivations were in equal measure banal, cowardly, and depraved.

The Ripper as Death personified as he escorts Mary Kelly to her room, on the front cover of The Illustrated Police News(8 December 1888). A truly grisly image.

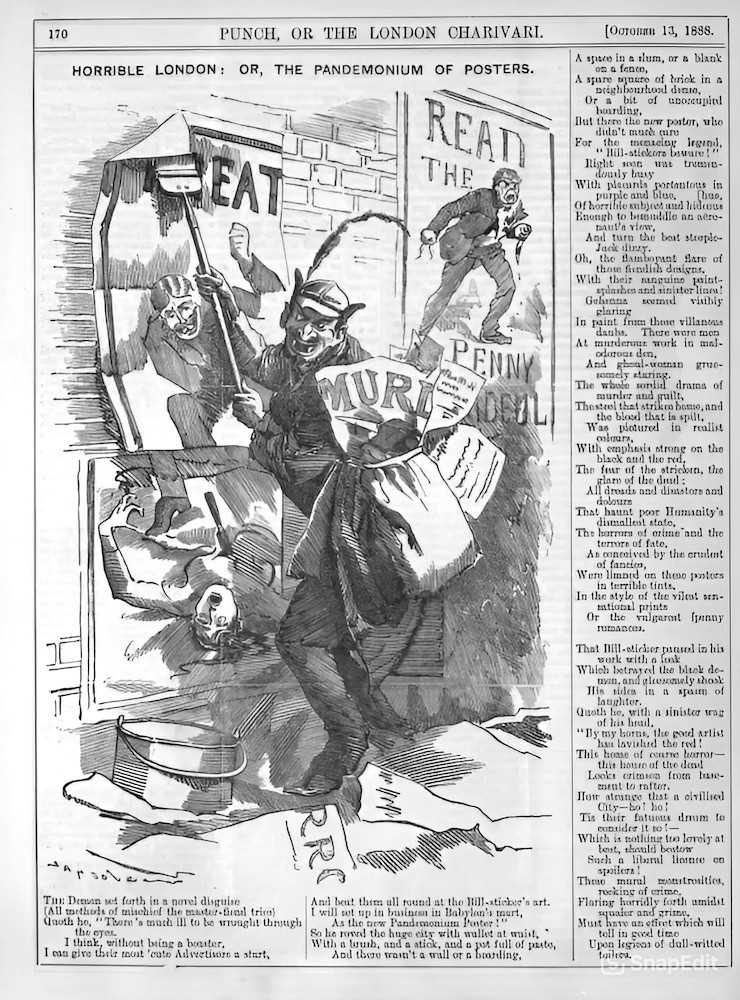

What is interesting, however, is the fact that commentators were aware of the process of mythologizing, of making it into a marketable commodity, at the very moment of its production. Punch astutely pointed to the way in which the Ripper phenomenon had been commercialized as a sensational experience. In Horrible London; or the Pandemonium of Posters, the excesses of vulgar advertising are linked to the murders in Whitechapel by showing a demonic figure – again an anti-Semitic type, and a surrogate for the Ripper – in the process of pasting up posters promoting a Penny Dreadful and a melodramatic play. One shows a woman who has been stabbed by a knife, a direct allusion to the Ripper, and the bill-poster is about to stick up another with part of the word ‘Murder’ as its headline. The implication of the whole is clear: murder is just another selling point, and the killings just another product to be sold and consumed in the pages of the papers. The Ripper story, Punch reflects, has been commodified, converted into a sensational scandal that appealed to the debased taste of the public and made considerable money for those who controlled the media. Like many a crime in our own modern age, the Ripper narrative was exploited for gain and inflected with capitalist greed. Alice Smalley reveals that in 1888 The Illustrated Police News had a circulation of 300,000 (13) – and it is not surprising that its publishers wanted to maintain its lucrative appeal, making sure that the Ripper tale took up more column spaces than any other story (Jones 85).

The Ripper and media capitalism, Punch’s take on the exploitation of a scandalous story (13 October 1888): 175.

There were nevertheless continuing anxieties about the dangers posed by the proletariat as symbolized by the Ripper. The metropolitan middle-classes felt vulnerable, and blamed the police for failing to protect society and social order by failing to catch the murderer. In Whitechapel, 1888 Tenniel depicts the widespread belief that the police had allowed crime to get out of hand as two miscreates celebrate the fact that they can conduct their business unimpeded, there being too few coppers on the beat to make any difference. The artist tellingly positions the figure of a policeman as he turns away into the background – a visual comment on the public’s understanding of the force’s underperformance: always there but not quite in time, the police were never effective and the Ripper always one step ahead of apprehension. The Ripper, it seemed, was taunting the authorities, just as in Tenniel’s image of sarcastic criminals. Justice was never being served, a notion exemplified in cartoons which repeated the notion of Blind Man’s Bluff, this time showing Justice herself being mocked by the incompetence of those who should have been upholding the law.

Left: Tenniel’s comment on the failure of policing – an event celebrated by criminals. Right: Justice blindfolded by the incompetence of the police, as shown in The Illustrated Police News (24 November 1888).

Some Conclusions

The Ripper phenomenon was inextricably linked to its time and acts as a multivalent sign of Victorian values which was constructed by the written and visual responses to the events in Whitechapel. Pictorial treatments reinforced and supported the writing of the crimes, but particular aspects of the Ripper’s significance were privileged visually: the idea of the seriality of the crimes was largely generated by the comic-strip narratives, and it is equally true that Jack’s supposed Jewishness was greatly extended by stereotypical portraits as they appeared in The Illustrated Police News. The concept of the murders as a threat to society at large was similarly promoted by the cartoons in Punch.

The body of images picturing the Whitechapel slayings can be read, in short, as a powerful materialization, a showing and embodying of the many anxieties surrounding this first, and most celebrated, of serial killings. The capacity of graphic art to focus and enshrine its material in a plastic form is a central part of this process, enabling us to see the Victorians’ fears in a distinctive iconography. Indeed, those visual forms have been influential, especially in the ways in which film and television have developed their own take on the imagery that appeared at the time of the Ripper’s brutal dominion. Seeing the Ripper was, and remains, a subject of fascination.

Bibliography

Primary Visual Sources

Cruikshank, George. Table Book. London: Punch Office, 1845.

Doré, Gustave. London. London: Grant, 1872.

Illustrated London News (1888).

Illustrated Police News (1888).

Penny Illustrated Newspaper (1888).

Pictorial News, The (1888).

Puck (1889).

Punch (1888).

Written and Secondary Sources

Anon [? W. T. Stead]. ‘Another Murder – and More to Follow?’ The Pall Mall Gazette (8 September 1888): 1.

Anon [?W. T. Stead]. ‘Is the Murderer a Malay?’ span class = "periodical">The Pall Mall Gazette (10 November 1888): 1–2.

Anon [?W. T. Stead]. ‘Number Nine.’ The Pall Mall Gazette (10 November 1888): 1.

Anon [?W. T. Stead]. ‘Polly Nichols’ The Pall Mall Gazette (1 September 1888): 9.

Anwer, Megha. ‘Murder in Black and White: Victorian Crime Scenes and the Ripper Photographs.’ Victorian Studies 56, no 3 (Spring 2014): 433–441.

Bloom, Clive. ‘The Ripper Writing: A Cream of a Nightmare Dream.’ Jack the Ripper: Media, Culture, History.. Eds. Alexandra Warwick and Martin Willis. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007. 91–109.

Cornwell, Patricia. Portrait of a Killer. New York: Little, Brown, 2002.

Cowling, Mary. The Artist as Anthropologist. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Curtis, L. P. Jack the Ripper and the London Press. Yale: Yale University Press, 2011.

Jones, Steve. The Illustrated Police News: London’s Court Cases and Sensational Stories. Nottingham: Wicked Publications, 2002.

Knight. Stephen.Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. London: Harrap, 1976.

Monk, Craig. ‘Optograms, Autobiography and the Image of Jack the Ripper.’ Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 12, no. 1 (Fall 2010): 91–104.

Oldridge, Darren. ‘Casting the Spell of Terror: the Press and the Early Whitechapel Murders.’ Jack the Ripper: Media, Culture, History. 46–55.

Robinson, Bruce. They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper. London: Fourth Estate, 2015.

Rogerson, Robert. Human and Animal Character. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1892.

Rubenhold, Hallie. The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. London: Doubleday, 2019.

Smalley, Alice. Representations of Crime, Justice, and Punishment in the Popular Press: A Study of the Illustrated Police News. Doctoral thesis, The Open University, 2017.

Walker, Alexandra. ‘Blood and Ink; Narrating the Whitechapel Murders.’ Jack the Ripper: Media, Culture, History. 71–90.

Walkowitz, Judith R. ‘Jack the Ripper and the Myth of Male Violence.’ Feminist Studies 8, no. 3 (Autumn 1982): 542–74.

Created 30 May 2025