In transcribing the Internet Archive version of the following article from the Magazine of Art, I have followed the house style of the Victorian Web and converted titles of books and artworks to italics. Click on images to enlarge them. —George P. Landow

hundred years have passed since Senefelder's first happy introduction — half discovery, invention — of the art of Lithography. The hundred-and-first is witness of a revival full of promise and already full of beauty: a revival possibly destined to rival the brilliant renascence of Etching which, realising how it had become the victim of its own foolish misconception of its functions and limitations, has but lately risen afresh from the degradation to which it had condemned itself. It was impossible that an art which consisted simply in the drawing with pencil, pen, or brush upon a stone, and rendered a ten-thousandfold harvest in the almost infinite number of its prints — or, rather, replicas — that might he multiplied from its surface, was one which could not willingly be allowed to die. It was not only that lithography was cheap and rapid and convenient; it was rather that it was the medium par excellence by which the line artist might reproduce his freely-made sketches and designs: — the means by which he might evolve his artistic dreams or dash off his most vigorous thought, with the certain knowledge that permanence and easy publicity were at his command. Thus would Gavarni first scrawl over his stone uneasily and at random, seeking inspiration from the scribbles that he made; or with feverish haste would throw the idea, upon it already formulated in his brain. It is clear enough, therefore, that artists' lithography, — that is Original Lithography, for I pay no heed to the less spontaneous art of the reproducer — is not, and could never be, the Lithography of the lithographer; and this is the saving fact on which we who love the art base our hopes and our judgment of the immediate future. Herein we are more sanguine than Mr. William Simpson, our greatest surviving English lithographer of the old school who wrote to me on this very point: “Artists seem always to etching, so that they neither learn the capability of Lithography nor acquire a knowledge of the process. I believe that if they did, and found what a beautiful means it is in the hands of an artist, they would prefer it. I have talked this matter over with Louis Haghe and with Robert Carrick, and both of these men — who were alike lithographers and water-colour painters of the highest repute — quite agreed with me on this point. But that is what there appears to be but small hopes of."

Venice: The Grand Canal

The hopes, on the contrary, are great. A powerful movement has been of recent years initiated, and exquisite work has been produced. Before, however, I proceed to explain this movement and to speak of the masterpieces of lithography lately produced, it is necessary that I should set forth briefly in this paper an outline of the art's history antecedent to the decline which paved the way for its revival with all its beauties fresh upon it, and all the lumber of past prejudice and malpractice left behind.

No sooner did Senefelder — the poor disappointed student of jurisprudence, the stage, and the drama — realise, as well as discover, the virtues of a calcareous stone, which through the application of grease would accept printer's-ink and through that of water repel it, than he quickly appreciated the importance of the invention he developed from it: and, more fortunate than most inventors, he drew upon himself the notice not only of the artists of his country, but of those, later on, of France, whither General Lejeune and the Count de Lasteyrie brought it back from Munich: and, later still, of those of England.

In Germany the new art, now duly recognised, was soberly taken up and widely practised, amusing the interest and commanding the "patronage" of the Court; but few of the artists of that country, save Adolf Menzel and one or two associates, took it very seriously. In France it quickly became a vogue; and the vogue, the rage: it was practised by amateurs royal, ducal, and other who boasted any claim to dilettantism. By the artists its reception was enthusiastic. The uncertainty of aquatint, the tediousness and expense of line-engraving, the chemical drawbacks of etching, all combined to carry forward the claims of the new method which, whether for original sketching or for purposes of reproduction, offered advantages belonging to no other process whatsoever. Goya, then an octogenarian and an exile at Bordeaux, experimented with it and obtained extraordinary results, and his few productions, executed in or about 1825, of which I would specially mention The Bullfight gave birth to what may be called lithographic Romanticism: for Delacroix saw them and spread their fame, and so gave rise to the second of the four periods into which the life of the art should be divided.

Infanterie polonaise marchant à l’ennemie by C. Raffet.

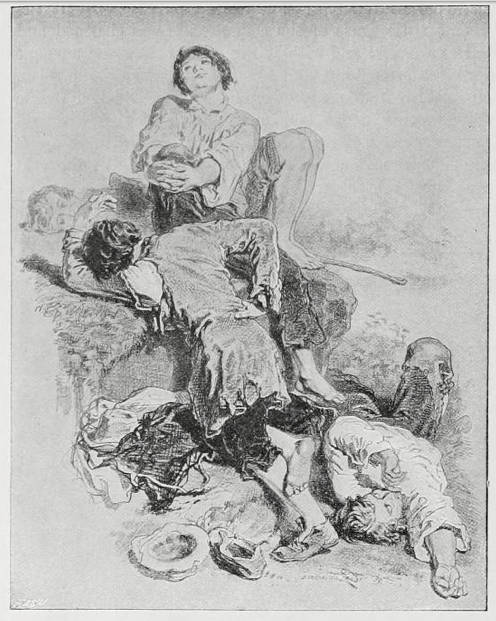

The first dates from its birth in 1830, during which interval the Baron Gros gave to the world his Mamelukes, Charles Vernet his Cossacks and his hunts (whose son Horace later delighted the world also with his studies of military life), Prud'hon his little comedies, Bonington his genre subjects, and Gericault his epics and then his horses. The second period extended from 1830 to 1840, when the romantic and the colorist school, headed by Delacroix and Isabey, reigned supreme, and Devéria put forth his portraits, and Henri Monnier bis scenes of Parisian life. From 1849 to 1855, or 1860, the glories of lithography — then, perhaps, the triumphs of subject and utility rather than exclusively of art and handling — were sustained by Charlet, Daumier, Raffet, Diaz, and M. Ferdinand Rops, who in their various styles carried the popularity of the art higher than it had ever been before. For the artists, its popularity was based upon technical considerations, so delicately and accurately responsive was it to every shade of the draughtsman's mood, to every touch of his skilful hand. For that reason Gericault, who executed only one single serious etching, besides a few studies of animals, produced a hundred lithographs: and Decamps seventy-three lithographs, and but a couple of etchings. Hippolyte Bellange, who etched not at all, so far as I am aware, put forth five hundred lithographs, and similarly, Delacroix, merely flirting with etching, in lithography produced his Hamlet and his Faust Daumier confined his wonderful colour studies and records, satires, and whatnot, to the stone in Mack and white, to the number of three thousand: and Gavarni, who detested the chemistry of etching, in his Comédie humaine alone executed as many. Indeed, the harvest of Daumier, Gavarni, and Raffet between them, amounts to seven thousand prints, all known. To these greal men lithography meant as much as etching did, nol to Rembrandl alone, but also the satirists like Gillray, Rowlandson, and Cruikshank, and as the wood-block meant to Tenniel.

Social life, satire, political passion, and red-hot patriotism kept the public interest in lithography alive, for it was the unique instrument — and how powerful a one! — for such a purpose. By it the artistic sense of the conoisseurs was charmed and caressed; and with it the country was one moment set a-laughing, and the next inflamed by passion. With it, too, Daumier and Gavarni rivalled Balzac upon the stone, and Charlet and Raffet “discovered” the army, glorified Napoleon, and deified the Empire. These men understood the true utility of the art; but others arose who, partly by carrying its technique to its extreme point (as the Americans carried wood-engraving), tired the public with it, and partly by using it for subjects for the rendering of which newer methods were more appropriate, dragged it down: and the dates 1860 and 1880 em lose its poind of debasement. Caricature, also, had become too violent, so that lithography turned rather to the representation of manners and customs. This duty was in time usurped by photography and "process;" artists were drawn aside by a rising popular interest, in etching; even architects in France al least abandoned it for the more flattering blandishmeuts of taille deuce; and the downfall of lithography was complete. A few faithful souls still practised it quietly, almost furtively; and to their sense and better instinct is due in no small measure the revival which is now reawakening the enthusiasm of the lover of art.

Left: United Germany! by Daumier. Middle: From Belgium and Holland by Louis Haghe. Right: Study by Gavarni.

The practice of the art in Belgium, whither it was carried by Jobard, needs little notice, for it produced no artist of cosmopolitan reputation save Madou. It sent us, however Louis Haghe to second, and, after a time, to head, the efforts of Samuel Prout in this country. As early as 1816 Ackermann had published the first lithographs of Prout, who soon became famous for his views of Continental cities and his extraordinary feeling fur architecture. His market-places, so naturally peopled, are still a delight tn look at, and make us feel, with Ruskin, that his are the only crowds the spectator feels inclined to get out of the way for. To their artistic beauties — one might almost say, to their perfection — Ruskin bears frequent witness, and when he declaims in Modern Painters against "the wretched smoothness of recent lithography" as compared with the manly work of Prout's bold and sometimes hasty touch and his "scrawled middle-tint," the student of lithography will appreciate the justice of the criticism.

Study by J. D. Harding.

But for all Prout's excellence — unrivalled and unapproachable, as Ruskin declared it — Louis Haghe became the mure important figure in the practice of the art. His main work consisted, it is true, in re-drawing on the stone other men's work: but his own sketches in Belgium and Holland are altogether admirable, full of quiet power rather than of force. His architectural detail was a little more made out than Prout's, and his lighting was excellently managed. He used but one tint at first, then two, and finally, before he gave up the stone altogether, three — black, blue, and ochre — yet the result was by no means what is now understood by chromo-lithography. I may here mention — what I have never seen printed — that Haghe's right hand was without fingers, a congenital defect, and that he did all his work with the one hand he was limited to; and, furthermore (although it comes not rightly within the scope of the present article), that his reproduction of David Roberts's Fall of Jerusalem was probably the finest piece of lithographic work ever executed in England, just as Robert Carrick's Blue Lights, after Turner, is to be considered for breadth and tenderness of effect the classic, as well as the first great, piece of chromo-lithography. J. D. Harding was an excellent artist whose touch with the lithographic chalk, especially when handling trees and foliage, is to all artists delightful: but neither his technical manipulation nor his graduating tints could be compared to Haghe's. He was very particular as to the white lights with which stone-artists made much effect — often, to my mind, illegitimate and illogical, even by the best of them; and although he was precise in teaching that they should "always be confined to objects which are in Nature positively white," he did not in practice, even in his finest work, which I take Picturesque Selections to be, always carry out his principles. Indeed, the lights taken out were used without proper effect, so that, instead of helping the plate, they often made the artificiality of it- the more apparent.

Then followed John Nash and Mr. William Simpson, the latter the better artist of the two and far the more versatile: and in romantic and historic art, Cattermole and Corbould; in the rendering of cattle and animals, James Ward, R.A., Mr. Sidney Cooper, R.A., and Frederick Tayler; in portraiture, J. H. Lynch and R. J. Lane, A.R.A. On these men, reinforced occasionally by Alfred Stevens and others of less note, fell the burden of sustaining England's reputation in the section of lithography, and made her paramount in the departments of tint, transfer, and lithography in colour, just as Germany was paramount in the exquisite finish of the work, and France in the higher plane of artistic conception and brilliancy of execution. Then, in due time, just as abroad the art decayed, etching usurped its place in public and artistic taste: wood-engraving supplanted it for book-illustration, and photography annihilated it for portraiture, just as the new "three-colour process" will assuredly dispossess it in the field of chromo-lithography.

Although Scotland had no printers like Day or Hullmandel, no Hanhart or Way to encourage her, she achieved at least one success in the art which must not be omitted. This was David Morrison, of Perth, who about 1830 illustrated with extreme taste and skill the catalogues of the library and paintings belonging to Lord Gray in Kinfauns Castle — book's to which Sir Walter Scott, refers in his notes to "The Fair Maid of Perth," but which I believe to be wholly forgotten by, or unknown to, lithographers in I his country.

It will thus be seen that in this country at least the field of Original Lithography, as at present understood, is practically virgin soil and promises a rich harvest. With the grease-pencil or lithotint-brush our artists have never given rein to their fancy, nor ever sought to express such artistic passion as may move them. They have hitherto been precise, deliberate, almost emotionless, and with relatively but little poetic feeling. Fact, not fancy, has been their aim. Lithography, indeed, has hitherto been chiefly used as a means only to an end; it will now be practised as its own end — for its own charm rather than for the opportunity it offered to record the beauties of architecture or to produce well-drawn models for the art-schools. It is the same new spirit, which is animating the artists of France and England both — a profound appreciation of lithography's own exquisite qualities and its capacity for rendering easily, beyond any other method, every gradation of tone, and of permitting the artist to attempt any problem he may choose. Power, force, tenderness — the whole gamut from black to white — all are within his reach, with a variety of technique offered by mi other process, except in a very limited sense by wood-engraving. How these remarkable qualities of lithography have recently been taken advantage of in the two countries, and what, the individual artists have achieved in this direction, will be set forth in my subsequent papers.

Related Material

Bibliography

Spielmann, M. H. “The Revival of Lithography. Its Rise and First Decline.” Magazine of Art. 20 (December 1897-November 1897): 75-79. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 5 November 2014.

Last modified 9 November 2014