[Revised and adapted from the author's article of the same title from Women's Studies Forum No. 8 (March 1994), Kobe College Institute for Women's Studies, Japan. Click on the illustrations to enlarge them and usually for more information about them.]

ppearance and demeanour are not infallible markers of a heroine,

though. Thackeray does tell us in the first chapter of Vanity Fair that Amelia Sedley, beloved by family and friends, is simply too blooming and

healthy (in other words, too pretty?) to be a heroine. Becky Sharp, on the

other hand, is pale and interesting. Moreover, her struggles have already

started: she has been beaten by her father in his cups, and dealt ably with

duns; since her father's demise, she has been exploited by Miss Pinkerton. She seems to fit the bill exactly. But she fails on another score. Heroines' spirits have always rallied to Becky's flag, but part of the irony of Thackeray's labelling Vanity Fair "A Novel without a Hero" is that what it really lacks, by Victorian standards at least, is a heroine.

ppearance and demeanour are not infallible markers of a heroine,

though. Thackeray does tell us in the first chapter of Vanity Fair that Amelia Sedley, beloved by family and friends, is simply too blooming and

healthy (in other words, too pretty?) to be a heroine. Becky Sharp, on the

other hand, is pale and interesting. Moreover, her struggles have already

started: she has been beaten by her father in his cups, and dealt ably with

duns; since her father's demise, she has been exploited by Miss Pinkerton. She seems to fit the bill exactly. But she fails on another score. Heroines' spirits have always rallied to Becky's flag, but part of the irony of Thackeray's labelling Vanity Fair "A Novel without a Hero" is that what it really lacks, by Victorian standards at least, is a heroine.

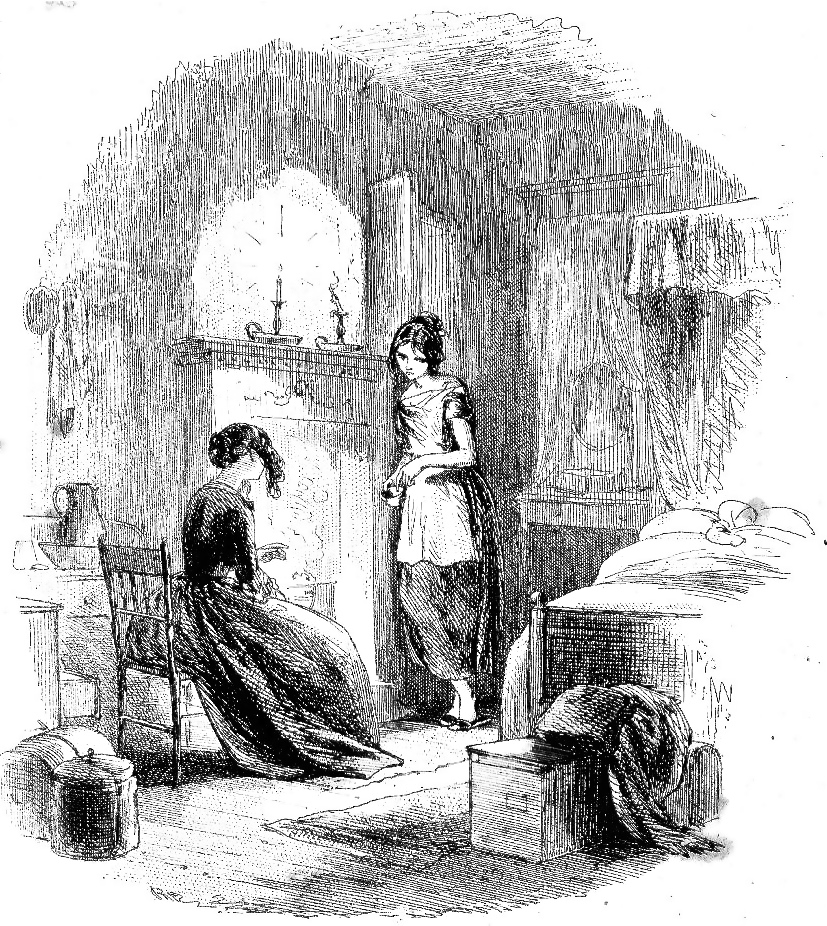

Caddy Jellyby pouring out her heart to Esther, about the state of her neglected home. [Click on the image for more details.]

The emergence from difficult childhood into the housewifely role, the eventual donning of the mob cap, so regularly describes a heroine's progress in the novel of this period that it can almost be said to chart it. The paradigm that Becky fails to provide is shown by Dickens's Caddy Jellyby in Bleak House. Hampered by a neglectful mother, trained only to cover herself in ink, the girl is inspired by Esther Summerson to try to raise herself above the disadvantages of her background. From Miss Flite she learns the rudiments of housekeeping, and soon leaves the desk for the kitchen. She prides herself on being able to choose cuts of mutton and make puddings. Her rewards for all this are a rather simple-minded and weakly husband, for whose inadequacy as a breadwinner she must compensate; and an even more weakly deaf and dumb daughter, whose care fills up her "scanty intervals of leisure" (933). Her fate seems harsh to modern readers, but, fretting under her earlier burdens, coping cheerfully and competently with her later ones, to G. K. Chesterton she is "by far the greatest, the most human, and the most really dignified of all [Dickens's] heroines" (157). This panegyric shows Chesterton identifying, in one of the supporting cast, the characteristic progress and attributes of a female lead.

Drawing attention to the abuses which could rob the young, in one way or another, of the precious childhood days which they had hardly known themselves, the Victorian novelists frequently target the irresponsible mother as well as coercive or negligent paternal authority. The result is that while sympathy is being evoked for many a young female character who is trying to establish her own identity and find her own way in life, a goal is also being held up for her far-from-distant future. This goal is one of devotion to duty, or, as Mr Meagles puts it to the once disgruntled orphan Tattycoram in another Dickens novel, Little Dorrit (offering the heroine of that narrative as an example), "active resignation, goodness, and noble service" (881). In due course, protest is expected to evaporate into paradigm, and produce — well, a paragon. The name provided for this paragon by Coventry Patmore, in his long poem sequence of that title is, of course, "The Angel in the House."

Dickens is not the only writer to promote domestic values. Male and female novelists collude here. Both condemn wives who leave their husbands, or mothers who busy themselves outside the nursery, to whatever purpose. Mrs Jellyby may be severely censured for expending her energies on missionary projects for darkest Africa, while her house is upside-down, her husband miserable, her daughter down-at-heel, her younger children's well-being, even their very lives, imperilled by lack of attention. But Charlotte Yonge sees to it that another mother's failure to breast~feed an infant, and to oversee the nursery properly, lead to the worst of disasters: at the end of The Daisy Chain, Flora's baby dies after being dosed with too much drug-laced "cordial" by an ignorant nursemaid, while her mother is out socializing.

Complete abandonment of children at any stage and for any reason is the ultimate crime, whether it takes place at birth — as in George Eliot 's Adam Bede, when it amounts to infanticide, — or later, as in Mrs Wood's East Lynne, where it gives rise to the most notoriously tear-jerking scene of the era after Little Nell's death in The Old Curiosity Shop: the death of the adulterous heroine's young son (the play made of the novel is the source of the well-known exclamation, "Dead, and never called me mother!"). In Adam Bede, a pointed contrast is made between Hetty Sorrel, the irresponsible mother, and the heroine, Dinah, who gives up her dream of being a Methodist preacher to become Adam's wife, and the mother of their biddable daughter and sturdy, vigorous son. Again and again the Victorian novelists confirm that devoted and (if necessary) long-suffering domesticity is the ultimate feminine ideal, and that any falling short is apt to produce unhappiness all round.

Becoming a heroine, then, is generally a matter of accommodation to a pattern, of living up to expectations raised in the eighteenth century by such model wives and mothers as Samuel Richardson's Pamela and Henry Fielding's Amelia. Perhaps such demands also owed much to the personal needs of writers brought up in the harsh regimes of the early nineteenth century.

Related Material

- 1. Introduction and "Plain Janes"

- 3. Difficult Passages

- 4. The Pain of Conformity

- 5. Finding an Occupation

- 6. The Next Step, and Conclusion

Bibliography

Chesterton, G. K. Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens. New York: Haskell House, 1970.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Ed. Norman Page. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

_____. Little Dorrit. Ed. John Holloway. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967.

Yonge, Charlotte. The Daisy Chain or Aspirations: A Family Chronicle. London: Virago, 1988.

Created 7 July 2018